History & Politics

Secrets of the Belvedere

As our city’s grand hotel turns 100, we reflect on her sometimes glorious, sometimes ignominious past.

In the twilight, from a distance, she still looks beautiful. With her fortress-like exterior, silverish-gray and augmented with pink terra cotta brick, she stands apart from the mostly muddy browns and other assorted earth-tones of her neighboring structures; dignified and distinctive, the color of a winter cloud at sunset.

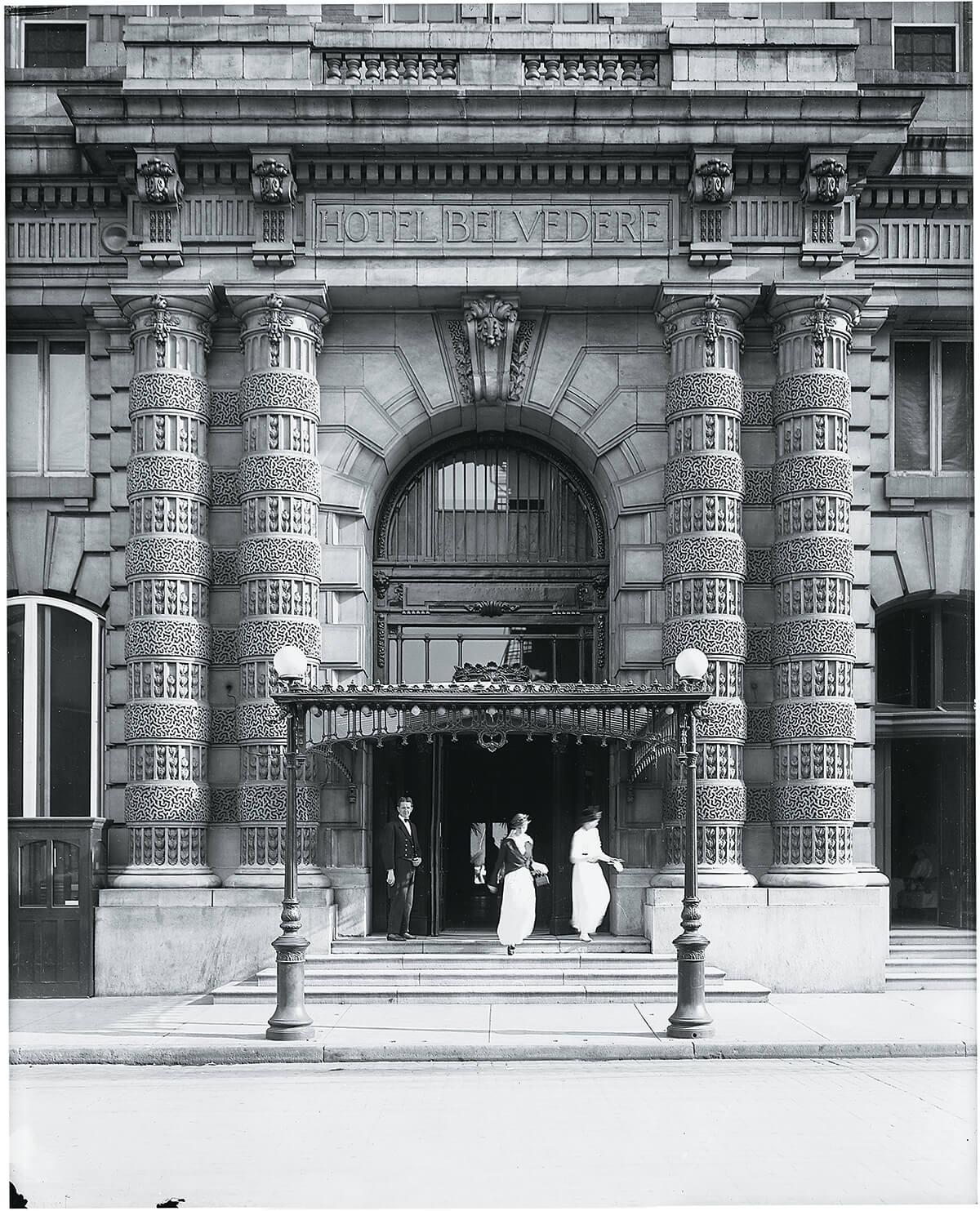

The Belvedere first opened in winter a century ago, on December 14, 1903. She looked like a castle then, too, sitting majestically on the corner of Chase and North Charles. This was quite appropriate, because the Belvedere—or Hotel Belvedere, as she was initially named and as the carved stonework above her grand entrance still reads—played host to some of the most famous and influential people alive. This was once upon a time, when Baltimore was a cosmopolitan city that drew the world to its doorstep.

Photography by David Colwell.

Royalty and presidents. Movie stars and music idols. Sports heroes and global explorers. Gangsters and detectives. Novelists and newspapermen. Developers and financiers.

And with the famous came the fabulous—opulent fêtes that were the very definition of conspicuous consumption. And infamous, as well—murders, scandals, naked women roaming the halls.

This month marks the centennial anniversary of the Belvedere Hotel. “Belvedere” means “beautiful view” or “beautiful to see” in Italian. And, like that rare beautiful woman who has lived a century among the wealthy and the blessed and the elite, the Belvedere keeps many secrets.

“Meet me at the Belvedere

Come before the show

Meet me at the Belvedere

And see everyone you know

Dining with society in a cozy nook

Mixing with celebrities to take a second look…”

—“Meet Me at the Belvedere” by Victor Frenkil

In order to comprehend the magnitude of the Belvedere’s construction and opening, it helps to get an understanding of what a top-notch hotel meant to a city at the turn of the 20th century. It was essentially the equivalent of landing a professional sports team: It signaled to the world that you had arrived, you were a player, you were on the map.

For the upper crust of Baltimore, this type of hotel was an imperative, for two reasons. First—though in the early history of the country, hotels were often viewed as places of ill repute—by the turn of the century, an individual’s travel lodgings were an indication of his or her place on the ladder of success. If a city did not have a hotel in which the visiting elite could recline and look sublime, well, then, how wonderful could that city really be?

But even more important to Baltimore’s growing moneyed class, a plush and regal hotel was needed as a place for capitalist royalty to gather, have parties, dance, gossip, do business and—most of all—be seen and recognized as the rich, powerful, and beautiful people that they were. The construction of a luxury hotel was designed not only to show off the city, but its high society, the so-called “400” of Baltimore’s Blue Book, who gathered there on a regular basis.

Thus, it’s no surprise that the initial $1.7 million to buy the land and construct the Hotel Belvedere—a staggering amount of money for the time—was put up by four of Baltimore’s wealthiest families, including one name that still towers over the city, Alexander Brown, as well as the Parr, Harvey, and Perin families.

The architecture firm of J. Harleston Parker and Douglas H. Thomas Jr, which designed the original Alex. Brown & Sons building on Calvert and Baltimore streets in 1900, was tapped by the gang of four to outdo themselves, spend whatever it cost and create the greatest hotel in the world—something European, elegant, exquisite, majestic, worthy of Baltimore’s aristocracy. They chose a design both populist and regal in the Beaux-Arts style, a style shared by New York City’s legendary Plaza and St. Regis hotels.

Almost instantly, the hotel was a hit. When she opened on December 14, 1903, two weeks before Christmas, with virtually no advertising, the Hotel Belvedere was immediately established as the place to be seen, drawing, according to The Sun, “All of the season’s debutantes…with their own parties or as the guests of others. The main dining room and six private dining rooms were filled to capacity and it was estimated that over 1,000 people dined…that evening.”

Here is a short and far from complete list of guests who stayed at the Belvedere: Clark Gable and Carole Lombard (often). Rudolph Valentino. Gloria Swanson. John D. Rockefeller. Andrew Carnegie. World Heavyweight Champion boxers Diamond Jim Brady and Gentleman Jim Corbett. Ty Cobb. Jane Russell. Lady Astor. Will Rogers. Roy Rogers. Oscar Hammerstein. Cecil B. DeMille. Tom Mix. Clare Booth Luce. Al Jolson. Enrico Caruso. The Duke and Dutchess of Windsor. Groucho Marx. General Douglas MacArthur. Admirals Richard Byrd and Robert Peary. Tommy Dorsey. Cab Calloway. B.B. King. Kenny Rogers. F. Scott Fitzgerald (infamously). The Smothers Brothers. Tyrone Power. John Philip Sousa. Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire (separately). Jean Harlow. Jane Wyman. Henry Fonda. Al Pacino. Queen Marie of Romania. Every U.S. President from Teddy Roosevelt to JFK, then toss in Reagan for good measure. Bishop Desmond Tutu. Chiang Kai-Shek. Shari Lewis and Lamb Chop (together).

To the powerful—and those they attracted—the Belvedere was a seductress. She had the best martinis in town, the best chef, the best maitre’d. Songs were written about her. Motion pictures were shot inside her.

Oh, if her walls could only talk. But sadly, many of the Belvedere’s secrets are lost to time. For not only was the hotel a grand getaway for the rich and powerful, she was quite powerful herself, particularly at squelching stories that might paint the palace in a less than regal light.

From before the beginning, the hotel operators understood that if you courted the press, you could control the press. The day before the Belvedere opened, there was an exclusive tour for members of the media—and back then, the media was pretty much the city’s newspapers, which included The Sun (morning and evening editions), the Baltimore Star, and the Baltimore-American—followed by a free banquet, with European culinary delights like oysters on the half shell, potage Ambassadeur, filet of sole, tournedos of beef, and quails farci a l’Estoufade. As The Sun noted, “There are a lot of newspapermen who have never enjoyed a dinner like that, and never will.”

This hand in glove—or perhaps fork on plate—relationship between the Belvedere and the press lasted about 50 years.

“Whenever somebody did a story that did well by the Belvedere, you could go up there and have a dinner on the house,” says Jim Bready, who was a reporter and editor for the Sunpapers in the 1940s and ’50s. “It was in the days before codes of ethics were being formulated by newspapers.”

The Grand Ballroom in 1908.

The Grand Ballroom in 2003.

Bready says that all the key editors in town—a hard drinking lot—were sent huge containers of the Belvedere’s famous martinis on Christmas Eve. Christmas was a good time to do it, because it was the season of some of the hotel’s wildest—and most notorious—parties. One such party was thrown by F. Scott Fitzgerald in honor of his daughter, Scottie—presumably to make her feel better because her mother, Zelda, had recently been committed to Johns Hopkins psychiatric hospital. Instead, Fitzgerald got completely smashed and humiliated poor Scottie by dancing with all of her young friends, then suddenly sending everyone home so he could sit in the ballroom all by himself and continue to drink. This event was too much for even the newspapers to ignore, and Fitzgerald left town soon afterwards.

Yet, for the most part, the scandals were kept mum for the first half of the hotel’s life.

This cozy relationship all came crashing down in the 1950s, when The Sun exposed the “Belvedere and Ballpark Night,” an annual custom where the town’s reporters came to the hotel for free dinner and drinks, then got packed onto a bus for Memorial Stadium where they were ushered to box seats practically on top of the field.

“This went on for some years, until the morning Sun did a story exposing it on the first home local page,” Bready says. “The reason they gave was morality, trying to show the difference between [the ethics] of the morning Sun and the Evening Sun. Actually, the difference was that the morning Sun couldn’t go. They were working, putting out the next day’s paper. It was the Evening Sun that profited from the relationship.”

After the exposé, the papers began to report more legitimately on the hotel. But before then, much of what we know about the Belvedere is a tantalizing mixture of gossip, cobbled-together memory, and semi-documented fact.

We know that in March of 1904, “Mr. Belvedere”—19-year-old William Francis Riesner—was hired as a dishwasher in Hotel Belvedere’s kitchen and began his rapid rise through the ranks. Stubby yet suave, well-mannered and always impeccably dressed, Francis—as he singularly came to be known—was named maitre d’hotel in 1919, a position he commanded for nearly 30 years until his death in 1949.

We know that from June 25 to July 2, 1912, more than 600 guests registered at the Belvedere for the Democratic National Convention. The severely overbooked hotel set up cots in hallways to accommodate the party faithful, who nominated the winning Presidential ticket of Woodrow Wilson and Thomas Marshall.

We know that on October 20, 1926, Queen Marie of Romania visited. And, while there have been literally thousands of grand galas at the Belvedere, this was undoubtedly the greatest. All of Baltimore society attended, as a canopy of royal purple was draped over the hotel’s entrance. The Queen’s suite was covered with silk and decorated with Louis XIV pieces, the Ballroom filled with hundreds of the Queen’s most favorite, fragrant roses. Francis even imported an ancient Italian throne and placed it upon a pedestal for the Queen to sit, and gold china stored in the Belvedere basement for over 20 years was hauled out (and partially stolen afterwards).

Clockwise from left: Margaret and Victor Frenkil at a fundraising party in the late-1950s; The Duchess and Duke of Windsor in the Windsor Suite of the Sheraton Belvedere, 1957.

Queen Marie of Romania in War Memorial Plaza after her luncheon at the Belvedere, October 20, 1926 ; Carole Lombard and Clark Gable, December 28, 1940.

We know that an aged and legless Sarah Bernhardt serenaded hotel guests in the lobby as she was carried into the hotel by sedan chair; that in 1946, four-star Chef Joseph Vallegant stood up to the Mob, which was robbing the hotel blind, and lived to tell the tale; we know of the 1913 night when French and Assyrian chefs had a huge screaming match over whether to put rose or carnation petals in the finger bowls (!) and the entire kitchen staff walked out, with more than 500 diners waiting to eat; we know of the day a woman guest complained about the man screaming next door and it turned out to be Enrico Caruso, practicing for his opera gig at the Lyric; and of the tragic evening in May 1937, when an overloaded hotel elevator went out of control, crushing the legs of two 21-year-old girls, caught between shaft and ledge, who were then trampled by the other panicked passengers on the way out.

But mostly we know about the parties: parties with exotic animals like camels and kangaroos. Hawaiian parties with giant four-foot clam shells, countless hula dancers, and monkeys, one party that even climaxed with a simulated Pacific typhoon (and ended with a wet bang when clean-up crews dumped the Hawaiian pond off the roof and inadvertently drenched the guests who were leaving below). Confederate parties, where the hotel flew the “stars and bars” flag on its marquee and decorated the lobby with portraits of Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson.

Today, when the hotel is quiet, you can swear you still hear the tinkling of champagne glasses and the distant strains of Tommy Dorsey.

The parties had to end eventually. And one sobering fact about the Belvedere is this: She never earned her keep. The hotel has had 18 owners in its 100 years, but it looks like only one—the Sheraton Corporation—walked away with any money in its pocket. She is a regal beauty, but she is high maintenance.

While the city’s high rolling forefathers originally instructed Parker and Thomas to spare no expense in building the place, they soon realized what that actually meant, and the Hotel Belvedere was up for sale even before it was completed. Slightly over two years after it opened, the property went into receivership in February 1906, and was purchased by the Maryland Trust Company for $1,500,000—a cool quarter million bucks less than it cost to build.

Hotel Belvedere was next purchased by Union Trust Company, who couldn’t make a go of it, and in 1915, with the first World War putting a damper on travel, the Belvedere went into receivership again. This time, it didn’t sell until 1917, when a Virginia hotel magnate and former circus clown “Colonel” Charles Consolvo bought the Belvedere for the rock-bottom price of $450,000.

Consolvo reorganized the place and took over managing it himself, and by the early ’20s, Hotel Belvedere was roaring. He moved into the hotel with his free-spirited wife and took over the entire second floor for their living area, where Mrs. Consolvo often scandalized visitors by walking around nude.

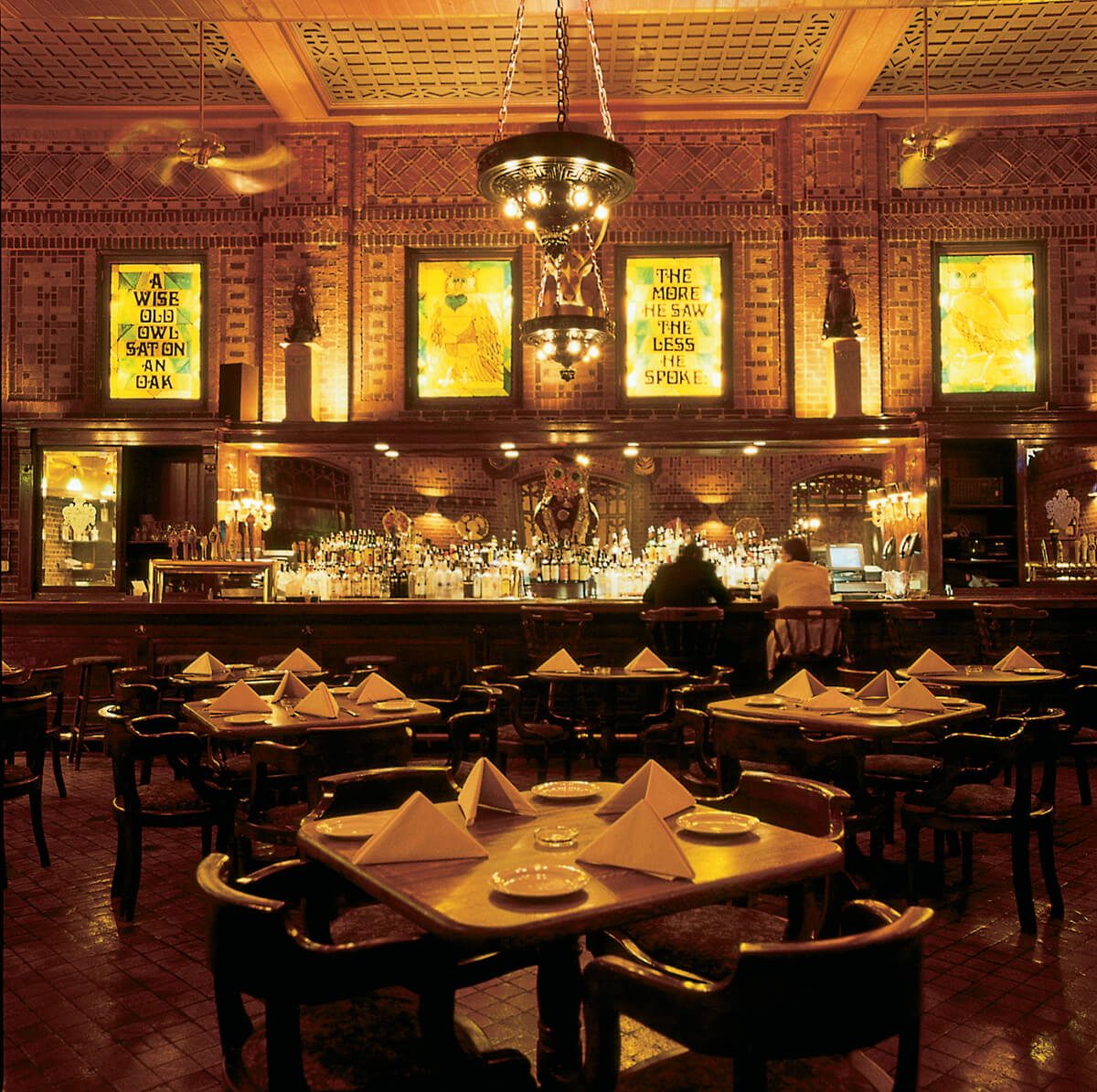

Consolvo ran the property at a profit—enough so that he could acquire the plush Jefferson Hotel in Richmond for $1.2 million—until Prohibition hit. Though he surreptitiously ran booze out of the place—bottled whiskey with an audacious Belvedere label, no less, and installed the now-notorious owls in the Owl Bar, which winked at patrons when it was safe to order the hard stuff —profits declined until the Depression, when Consolvo was forced to declare bankruptcy.

In 1942, a group of rich Baltimoreans—including theater patron Morris Mechanic and John McFee Mowbray—bought the hotel from the bank for an undisclosed sum. They held onto it for four years, through the end of the war, then sold it to the Sheraton Hotel Corporation in 1946, an arranged corporate marriage that caused her name to become the hyphenated Sheraton-Belvedere. It might have been a decision made because of money instead of love, but it worked. The next 22 years were the hotel’s most financially stable, though the following five would be her absolute worst.

It was during her time as the Sheraton-Belvedere that the hotel experienced her finest hour. It lasted about a month. Baltimore in 1954 was a racially polarized city. Segregation was the norm, and hotels—especially upscale hotels—were no exception. But the Sheraton-Belvedere wanted to set new rules. One week before Christmas, 1954, Sheraton Corporate hotel manager Albert Fox made a bold decision to welcome African-American guests to Hotel Belvedere. Considering the holiday season, it certainly seemed the Christian thing to do, and Fox later told The Sun that business at the hotel increased significantly.

The world did not stop, but the Baltimore old guard was apparently aghast. Though the particulars are a bit foggy, it seems the Baltimore Hotel Association threatened to throw the Belvedere out of its membership. It was made clear that in Baltimore, hospitality should remain a monochromatic enterprise.

Officially, Fox told The Sun he received no threats or intimidation, but added, revealingly, “If you’re going to belong to an organization…you have to comply with the rules of that organization.”

The Sheraton-Belvedere reluctantly acceded to the wishes of the Baltimore Hotel Association and returned to refusing Black patrons on January 17, 1955.

As for the newspapers, well, none of them covered the desegregation story at the time. It took until March, 1955, almost two months later, when Maryland Governor Theodore R. McKeldin finally made an issue out of it and the media couldn’t bury their heads in their martinis any more. McKeldin slammed the Baltimore Hotel Association following a report from the Maryland Commission on Interracial Problems and Relations that examined what happened at the Sheraton-Belvedere the holiday season prior.

The Commission’s report got a one-column, thirteen-paragraph story in The Sun, buried inside the paper.

When the Sheraton Corporation was sold to ITT in 1968, the Belvedere began a rapid downward spiral. Less than three months later, the Belvedere itself was sold by its new parents in an 18 hotel package deal to Wellington Associates. Wellington promptly resold the hotel to Gotham Hotels, Inc., who ran it into the ground and closed it.

She then reached her lowest point in September 1971, when, for a brief but horrible period, the Belvedere was leased by Gotham to the shady Snowden Corporation, which was headed by a Dr. Millard G. Roberts, a rather notorious businessman who would reportedly do anything for a buck.

Roberts’ new scheme was to turn the grande olde dame of Baltimore into a low-rent communal dorm for Baltimore students at 35 area colleges and universities. It was like Audrey Hepburn marrying Adam Sandler. Or worse.

Drug dealing was rampant. There were rapes. Trash pickup was irregular and bags of garbage built up in the halls, until windows of the ballrooms were broken out and debris discarded that way. Fire extinguisher fights flooded hallways and dripped down to the floors below. The power was turned off. Then on. Then back off.

In late January, 1972, Baltimore City closed the Belvedere for extensive code violations and the students were evicted.

Gotham defaulted on the mortgage payments for the Belvedere in August, 1972, and the hotel was put up for auction yet again. There was one bidder: Monumental Life Insurance Company, which sat across Chase Street. They paid $700,000 for the property, less than half what it cost to build 70 years earlier.

It took developer Victor Frenkil to save the Belvedere, and, in a way, it took the Belvedere to save Victor Frenkil. If, originally, Hotel Belvedere was built for Baltimore society to impress the rest of the world, Victor Frenkil bought the Belvedere to impress Baltimore society.

“The Belvedere was sacred to old Baltimore,” says Edward Hanrahan, a long-time friend of Frenkil’s who handled PR for the hotel throughout the late ’70s and ’80s. “Victor was never a part of old Baltimore society but he thought this might be a way to make them like him more, and it did. Not as much as they should have liked him, but it made a difference.”

Though terms weren’t initially released, it was later reported that Frenkil bought the Belvedere in 1976 for $650,000. He then secured a series of controversial loans from the city with the support of then-mayor William Donald Schaefer, as he sought to rebuild the place, first making it into apartments, then, at the behest of the city, turning it back into a hotel, then trying for a hotel and apartment mix.

Frenkil had a grand vision for the Belvedere, some of which got done, and some didn’t. He turned the 13th floor cloakroom into Top of the Belvedere (now The 13th Floor) bar. He officially named the bar at the Belvedere the Owl Bar, and brought back the owls, which had been stolen (although Hanrahan now claims to have had them all the time and the entire “hunt for the owls”—which was a huge story at the time—was an elaborate PR stunt that worked fabulously). He built the garage next door, which became a cash cow for him. He installed a swimming pool and racquetball court on the second floor, getting rid of some of the offices. The downstairs coffee shop was turned into shops and offices.

The Owl Bar in the early 1950s (then called the Falstaff Room)

The Owl Bar in 2003.

Other things he was never able to pull off. There were plans to put a glass elevator on the backside of the building that would take guests from the parking garage to the Top of the Belvedere. Expanding the marble staircase was cost prohibitive, so the entire grand marble staircase of the hotel was destroyed—Frenkil engraved little square blocks of it and gave them away as paperweights.

But he made a good go of it, spending millions of his own dollars, but the loans from the city kept coming as the red ink covered more and more sheets of paper. When Baltimore Mayor William Donald Schaefer moved on to the governor’s office, a new administration was not nearly so amiable to Frenkil or the Belvedere. He was forced to sell it in 1991.

His son, Victor Frenkil Jr., who remained in the Baltimore area and now works for Jarvis Steel & Lumber in Brooklyn, removed the owls from the Owl Bar for his dad to keep.

“I took the owls when my father lost the hotel,” says Frenkil Jr., 66. “They were damaged. They were bruised. I had them restored and gave them to my dad as a present, for the memories. He kept them less than a week and then said. ‘These things don’t belong here. They belong to the Belvedere. They belong there.’”

“This whole Belvedere thing with my dad made no sense whatsoever,” Frenkil says.“It was a labor of love, the numbers didn’t make no sense. He could have just torn the building down and built something cheaper. But he didn’t because he loved it.”

Frenkil Sr. died in June of 1998 at the age of 90. Not long before, Schaefer and other friends held a tribute to him at the Belvedere, where he sang the song he wrote, “Meet Me at the Belvedere,” accompanied by piano, one last time.

Of course, no legend of a great hotel would be complete without murders, suicides, and a ghost or two, and the Belvedere does not disappoint.

Being the tallest building in Baltimore for many years, the Belvedere inadvertently welcomed several depressed guests whose sole purpose was to take an early exit through an upper floor window. The most notable of these, according to a 1970s issue of this very magazine, went streaking downward past the living room window of Albert Fox, the manager of Hotel Belvedere at the time.

That story is a fact, but the hotel’s first murder and its ghost may both be legend, since nothing can be found in the newspapers of the time—though from what has been learned about the period’s selective reporting, its absence could hardly lead you to conclude a killing didn’t take place.

Two men—Joe Otterbein, who worked at the Belvedere in the late ’80s, during its last gasp as a great hotel, and Tom Hamrick, the current general manager of the Owl Bar and The 13th Floor bar—both recount hotel oral history that tells of a Baltimore woman in the 1920s or ’30s who caught her husband dancing with his mistress in one of Hotel Belvedere’s ballrooms and shot him dead. His ghost, it is rumored, still haunts the ballrooms of the 12th floor, but it only bothers women.

“None of the girls ever wanted to work up there by themselves,” Otterbein says. “Once in a while, people who worked up there would swear that glasses would fall to the floor and break with nobody nearby, or they’d put something down and a little while later it would be somewhere else.”

As for the second murder at the Belvedere there is no doubt, and its story is pretty squalid. During a period when the hotel was abandoned, Samuel Shapiro, owner of a number of parking lots around the city—including the garage next to the Belvedere—and a two-time gadfly candidate for Baltimore mayor, was shot dead in the lobby of the hotel by a former employee. Shapiro’s body was dragged to the Owl Bar and stuffed into a trunk that ultimately proved to be too small. The killers searched the hotel until they found a larger crate on the 11th floor which accommodated the corpse. (In an odd postscript, the convicted murderer, Douglas Arey, who was sentenced to life, was later the successful bidder for a lunch with then-Governor William Donald Schaefer during a benefit auction for the Center Stage. Schaefer refused, incidentally.)

Finally, near the end of Victor Frenkil’s ownership in the late 1980s, a maintenance man who lived in the building’s sub-basement near the building’s belching furnace, was killed by a former employee he’d fired the day before.

There were also at least two fictitious murders at the Belvedere. During its seven-year run, Barry Levinson and David Simon’s NBC crime series Homicide visited the Belvedere three times: Twice for killings—the first time a prestigious chef, the second a lowly maid—but also for the wedding reception of Detective Meldrick Lewis (Clark Johnson).

“Meet me at the Belvedere

Right after the show

Meet me at the Belvedere

It’s the last place to go… ”

In the daylight, up close, she shows her age. Standing on a Chase Street sidewalk on a wispy fall afternoon, a visitor needs not look closely to see the splotchy watermarks, like age spots, that garnish her façade. Or the small winding cracks through her stone, the wrinkles that come with changing fortune and time, which are covered up with paint and other forms of a mason’s masking make-up.

Inside the lobby, no longer bustling and now colored with a near-sepia tone of melancholy memory, there is the whiff of mildew. Off to the left and past walls of mostly dead celebrities’ pictures, before you reach the Owl Bar, The Palm Room is plagued by water leaks, though the pool that was installed above during the reign of Victor Frenkil now lies drained.

Upstairs, on the 13th floor and inside the bar of the same name, windows that still provide a breathtaking panorama of the city also reveal that the dormers a floor below are badly in need of paint, chipped and streaked with rust. Still, the view remains the best in the city.

A century has passed and her best days are behind her, though her worst, hopefully, are too.

Today, as a mixed-use condominium, the Belvedere serves many masters. Residents can purchase individual living units, efficiencies or one-or two-bedrooms, ranging in price from about $60,000 to $300,000. The Owl Bar, party rooms, dining rooms, ballrooms, and 13th Floor bar are owned by the canny and flamboyant businessman Tom Stuehler and his catering firm La Fontaine Bleu. It is Stuehler who largely deserves to be credited for keeping the property functioning as a quality Baltimore presence. Finally, there are the restaurants and shops in the basement, including a pretty good sushi bar. But the days of celebrity and fame are behind her, probably forever. All the hot hotels are down by the water now, chasing tourists’ green near the brine.

And yet…she still stands. She still has her past, her history, her memories, entwined with the city’s, tangled to a time that must not be forgotten, knotted tight to its greatness. She still has her aura. She is still worthy of her name. She is the Belvedere.

“Meet me at the Belvedere

And see everyone you know

Drinking with society

Sipping with celebrities

To take a second look

They’ll drink a toast to you

At the Belvedere

You are who’s who!

Let’s go to the Belvedere…”