Arts & Culture

All That Jazz

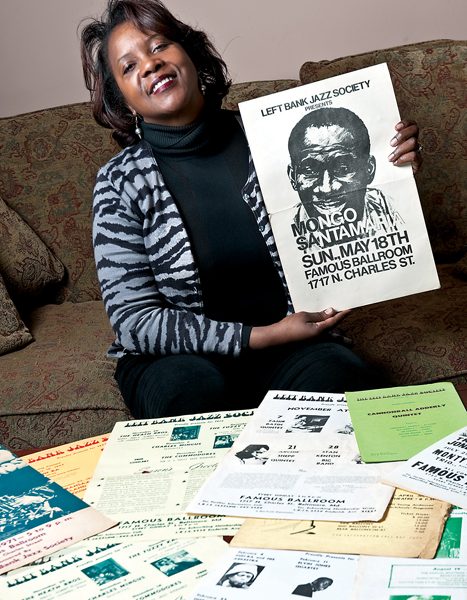

Desiree Collins was just looking for an investment property—she found a treasure trove of local jazz history.

When Desiree Collins stepped into Benny Kearse’s house in 2001, she wasn’t looking for a piece of history. She was looking for an investment property. Kearse, who lived in the 2800 block of Brighton Street in West Baltimore, had passed away two years earlier, and his house was being auctioned.

“When you buy a house like that,” says Collins, “you have about ten minutes to go inside, look around, and see if it’s structurally sound. You always come across leftover junk, and Mr. Kearse didn’t throw away anything. That house was full of stuff.”

Collins won the auction and, soon after, began emptying the house of its contents. “It took me and my husband an entire month to clean it out,” she recalls. “I like to go through the stuff carefully, because people sometimes have treasures in those houses.”

Sitting in the living room of her Halethorpe home, Collins says that besides being a packrat, Kearse must have been an avid reader and a history buff. “As far as magazines and papers, he had everything under the sun,” she says. “Newspapers were stacked to the ceiling, and he had books up the ying-yang.”

Collins points out framed Jet magazine covers featuring Aretha Franklin, Malcolm X, and the March on Montgomery hanging on her wall, next to an Ebony cover with Frederick Douglass. “They came out of Mr. Kearse’s house,” she says.

So did the boxes piled in the corner. “I ran across all these boxes and stacks of stuff about The Left Bank Jazz Society,” says Collins. “I’m not a jazz aficionado, but I knew I shouldn’t throw it away. So I just stacked it in my basement and figured I’d get to it someday. Last year, I finally started going through it to see exactly what I have.”

What Collins has is an extensive archive documenting the activities of one of Baltimore’s most important cultural institutions. Kearse, as it turned out, was a cofounder and president of The Left Bank Jazz Society, which mounted a spectacular run of jazz concerts going back to the 1960s. The group brought a who’s who of jazz greats to Baltimore, including Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Count Basie, Charles Mingus, Herbie Hancock, Freddie Hubbard, Sun Ra, Wayne Shorter, Sonny Rollins, Dexter Gordon, Chet Baker, and McCoy Tyner. John Coltrane’s last concert was a Left Bank show.

The boxes in the corner are stuffed full of Left Bank ticket stubs, fliers, brochures, business cards, letterhead, photographs, and financial statements. There are also press kits, old 78s, neighborhood newsletters, and copies of jazz magazines such as Downbeat and Metronome. “It dawned on me that this stuff had to be important,” says Collins. “It was too much history to just toss aside. All together, it tells about a vital part of this city’s—and this nation’s—culture.”

The Left Bank Jazz Society was formed in 1964, the year the Civil Rights Act was passed, at a time when membership in this sort of club had social and political implications. Left Bank grew out of the Interracial Jazz Society—Kearse had been a card-carrying member—a pioneering group that formed in the mid-1950s to promote jazz and, as its name implied, break down racial barriers at local clubs. Left Bank carried on that tradition.

“I was active in both groups,” says Maxine Smith, a Left Bank regular who went on to book jazz shows in Baltimore, Washington, D.C., and the Virgin Islands. “At their shows, it didn’t matter who you were, what race you were, everyone was welcome.”

The Left Bank’s constitution encouraged exactly that, stating its members should “share a love for Contemporary American Jazz Music, and . . . a belief in the democratic ideals of freedom and equality, regardless of race, creed, or color, which this music exemplifies.” Kearse, Left Bank’s first president, was black. Its second, Vernon Welsh, was white.

“As far as race relations, everyone was friendly at our shows,” says Mildred Battle, a longtime member and current Left Bank president. “Back then, it was amazing to see, because it didn’t happen in very many places. But jazz brought people together.”

Its ideals were lofty, but Left Bank was mostly about the music—and having a good time. Its early shows were held at The Al-Ho Club in South Baltimore and The Madison in East Baltimore, before the concerts were moved to The Famous Ballroom in the 1700 block of North Charles Street in 1966. Its mailings were often emblazoned with the slogan, “See ya at the Famous.”

“It was like a big old house party, or social club,” says Sandy Jordan, a Baltimore native and wife of the late saxophone great Clifford Jordan. “The same people came week after week, and some people had to be sick to ever miss a concert.”

Most of the shows were held on Sunday afternoons at 5 p.m. Admission was usually $6. “You could bring your own food and booze,” recalls Jordan, “and they sold set-ups [for mixed drinks]. They also sold soul food.”

A menu found in Kearse’s collection lists platters of chitterlings and hog maws for $2.20, and ribs for $1.95. Sides—greens, string beans, or potato salad—were 40 cents.

“You couldn’t ask for a better-spent afternoon,” says Jordan, who married Clifford between sets of a Left Bank show featuring Carlos Garnett. “We had the wedding and the reception right there at The Famous—we didn’t need to hire a band or a caterer. It was so much fun, but that’s the way it was every Sunday at Left Bank. It was a constant.”

The Kearse archive confirms a consistent stream of A-list talent and offers a peek at a thriving jazz scene. A Left Bank yearbook for 1968 includes a list of the group’s concerts from August 1964 to April 1968. Early on, local saxophonist Mickey Fields was a regular attraction, and Baltimore native Gary Bartz also performed that first year. The legendary Dizzy Gillespie played his first Left Bank show in December 1964.

From that point, the greats kept coming, and Left Bank really hit its stride in 1967, as Kenny Burrell, Jimmy Heath, Roland Kirk, George Benson, Yusef Lateef, Freddie Hubbard, Milt Jackson, and John Coltrane appeared on successive Sundays. “When we organized the group we knew we had to bring big name stars into the city on a regular basis in order for people to become familiar with them,” Kearse noted in the yearbook.

That yearbook also includes a review of Coltrane’s last show—he passed away two months after his Left Bank appearance—and an intriguing tidbit: “After expending an incredible amount of energy in a long first set, [Coltrane] sat at the piano bench during his entire intermission, making himself available to the many people who wished to speak with him.”

The anecdote says a lot about the atmosphere at the shows, as well as the sophistication of the Left Bank audience. “For years, musicians would tell me about playing for The Left Bank,” Atlantic Records producer Joel Dorn told Baltimore in 2000. “Over and over, I’d hear, ‘They have the hippest audience in the world. A Left Bank audience is like the fourth member of a trio, or the fifth member of a quartet.'” (In 2000, Dorn released a series of CDs culled from recordings made at Left Bank concerts.)

“The musicians loved to play for our audiences,” says Battle. “They loved it so much that the biggest names in jazz played here for much less than they could get elsewhere.”

Kearse’s handwritten financial statements seem to confirm that. Here’s the accounting from a 1973 Charles Mingus concert:

Cost of concert $1,756.65

Door monies $2,267.55

Profit $510. 90

Head count 656

A 1979 contract with Sun Ra’s Arkestra guaranteed the band $1,500, a pittance for a group that often included a dozen players.

Other materials in the Kearse archive, not directly related to Left Bank, further document a bygone era. There’s a poster for 1969’s Morgan State Jazz Festival featuring Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, and Booker T and the MGs; a flier noting that radio stations WFBR, WEBB, WBAL, WWIN all had jazz shows; and copies of The Nitelifer, a neighborhood newsletter that provided a street-level view of the local scene.

The June 1965 issue, for instance, includes an editorial about making the streets safe (“unless we are willing to turn Our Town over to the hoodlum element, drastic action is absolutely necessary”); shout-outs to various establishments (“The Hilltop, recently integrated, has one of the nicest, most courteous atmospheres to be found anywhere”); and ads for Jones’ Cocktail Lounge (“You’re only a stranger here once”) and the Storyville Record Shop (“Open weekends ’til 3 a.m.”).

But as musical tastes shifted towards funk and hip-hop, jazz became more of a niche market, the scene lost much of its vitality, and Left Bank struggled to retain its following.

After losing its home base at The Famous in 1985, Left Bank continued booking shows at Coppin State University and the Teamsters Union Hall on Erdman Avenue, but it wasn’t the same. “Attendance really dropped off in 2000,” says Battle. “We always got by on what we took in at the door and contributions from members, so it became very difficult for us at that point.”

Left Bank hasn’t put on a show since 2002, but Battle insists the organization isn’t defunct. “Left Bank has not died,” she says. “It’s just hibernating. We’ve been strategizing about how we could come back.” Beyond that, she doesn’t elaborate.

Still, Left Bank retains near-mythic status around town. That’s why Collins was hoping to keep the archive intact by making it available to a local museum or university.

But response was lukewarm, at best. “I was taken aback,” she says. “I contacted all these places in Maryland about this rich culture we have, and nobody showed any interest. I don’t know why Baltimore isn’t interested in this. It’s a mystery to me.” (For her part, Battle says she’d like to see what Collins has.)

As word of her find spread among jazz fans, Collins did hear from a few auction houses. “They put me in touch with some people who wanted to buy this stuff,” she says. “But I didn’t want to do that.”

She put a few duplicate items on eBay, and “they sold immediately,” she says. “The people who bought that stuff wanted more.”

Despite that, Collins doesn’t want to sell the collection piecemeal for maximum profit. In fact, she still hopes to find a home for it in Baltimore. “That’s where it belongs,” she says, “so people can understand what went on here, so they can see what Mr. Kearse and the folks at Left Bank created and achieved. I want to make Mr. Kearse proud.”