Sports

Ode to the Poets

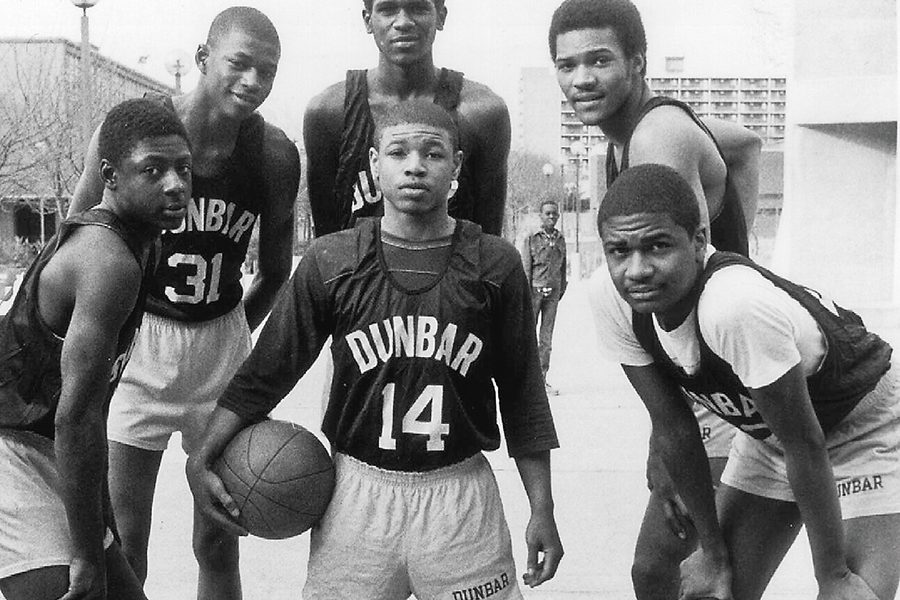

Thirty years ago, the Dunbar Poets were the greatest show on hardwood.

Inside Paul Laurence Dunbar High School’s windowless gymnasium, the air is thick with humidity—and history. Today is winter solstice, yet outdoor temperatures in the 60s have transformed the home of Baltimore’s premier high school basketball dynasty into a furnace.

The Poets are systematically slicing up overmatched Carver High, a scene that harkens back 30 years, when the most talented of all Dunbar squads steamrolled shell-shocked opponents before standing-room-only crowds of sweat-soaked spectators.

“It was so hot in the gym from all the fans in there, if you just got your hair done it came out wet,” says Michelle Wood, a Dunbar alum who watched her future-husband Darryl on that 1981-82 team. “You couldn’t hear yourself think.”

“It was electric,” says sportscaster Keith Mills, who covered Baltimore high school sports for WJZ-TV at the time. “When you walked into Dunbar’s gym during that era, it would be like a hip-hop concert today. There were big speakers, you had music blaring—it was a big event. I don’t think we’ll ever see it again. That was a unique time.”

And a unique team. Those Poets featured four players destined for successful careers in the NBA, including three taken in the first round of the 1987 draft.

“To watch them move on the court, it was like watching a symphony,” says Derrick Jones, an ’82 Dunbar grad and lifelong Poets fan. “They played like a Duke, a North Carolina team. You could feel the gym shaking with the students stomping on the bleachers. ‘We are the Poets, the fighting mighty Poets!’ Our Dunbar team, they were the best. They would have stepped up to any challenge.”

Three decades later, that remains hypothetical. While Dunbar went undefeated (rarely playing a close game), it never faced the country’s other true power, which happened to be in its own backyard. Yes, the 1981-82 Poets are inarguably one of the greatest high school basketball teams ever. But oddly enough, they might not even have been the best boys varsity team in their hometown.

Dunbar’s sterling basketball tradition already was long established, though in a bit of rut, when a big man with a no-nonsense attitude named Robert P. Wade took over the head coaching job in 1975. A former NFL defensive back for Vince Lombardi’s Redskins, Wade played both basketball and football for Dunbar.

By the 1981-82 season he had assembled a Poets team with junior stars “Muggsy” Bogues and Reggie Williams, and senior David Wingate. Just how he did it was the subject of speculation and grumbling among rivals.

Wingate, like Bogues, took advantage of Dunbar’s status as a college preparatory school offering career paths in health and medical fields to transfer in. What’s more, the school sits just a long three-pointer from the former Lafayette projects where Bogues grew up, but recruiting players to public schools was against the rules, and opposing coaches cried foul.

“Dunbar’s always been the family school for that part of public housing,” says Wade, who’s steadfastly denied wrongdoing. “I was fortunate enough that Muggsy’s sister was a star player on the girls’ basketball team. The brother, Anthony, played football and basketball. I watched him, not literally, grow.”

That’s a joke, of course. Bogues is the most famous Poet, known for his stature both on and off the court. At 5-foot-3-inches, he is the shortest man to ever play in the NBA. The 12th-overall pick in the ’87 draft, his amazing career stretched 14 seasons.

“Back them, it was the best show in town for $1. There will never be a team like that again.”

“I don’t remember ever growing,” he says. “I think my mama had me when I was 5’3”. Of course, you always kept hearing the negative—Muggs, you’re too short. But I was a kid, and I had the courage to keep playing and not care what people thought.”

Today, some, including Keith Mills, think he was the most dominant basketball player in Baltimore high school history.

“Muggsy controlled the game offensively and defensively,” he says. “You couldn’t press him, and you could not handle his pressure when he went after the ball. You talk to the guys he played with in [the NBA], and they looked at Muggsy Bogues like he was Jesus Christ. He was a God to those guys.”

Bogues transferred from Southern High, enrolled in health-care classes at Dunbar, and immediately began giving opposing point guards the chills. In Wade, he found a coach who both believed in him and worked him ruthlessly.

“We didn’t have the fancy weight equipment at Dunbar, so I just tried to improvise,” says Wade, now coordinator of athletics for Baltimore Public Schools. “I noticed that late in ballgames kids become winded, and, defensively, they begin to drop their arms. I tried to improve their stamina, endurance, and strength. So we did all of our drills with bricks.”

The impact of those bricks extended beyond the players’ physiques, to their pysches. Go to an Archbishop Carroll High School practice in Washington, D.C., where Williams now coaches, or to United Faith Christian Academy in Charlotte, North Carolina, where Bogues wears the whistle, and you’ll see players working out with bricks.

“We were in tip-top condition, so once the ball went up we were ready,” says Williams, who starred at Georgetown before playing 10 years in the NBA. “We did calisthenics, jumping jacks, sprints, everything with those bricks. We couldn’t drop them on the floor. After those three-hour practices, we would run with bricks. By the time of the game, we were mad, and we took it out on the opposing team.”

Throughout the ’81-’82 season, it was actually practices that presented the Poets with their fiercest competition.

“We felt like we had the No. 2 team in the country on our bench,” Bogues says.

Darryl Wood, who went on to play for Virginia State and serve 23 years in the Marine Corps, backed up Bogues. Reggie Lewis, then a shy, skinny kid, couldn’t crack the starting lineup. Five years later he was drafted 22nd overall by the Boston Celtics and became an all-star. Tragically, Lewis suffered a heart attack and passed away at the age of 27 in 1993.

“Our practices were tougher than the games,” says Tim Dawson, the team’s starting center. “They were so brutal, when the first couple of games rolled around we saw how easy it came to us. Having a game was like having a day off of work.”

To this day, Wade’s players don’t resent him for his rigorous practices, they revere him for it. When Bogues decided to give high-school coaching a shot, Wade was the first man he called. Dawson thanked the coach in his Ph.D. dissertation, and keeps a picture of him and his Dunbar teammates on his desk at South Hagerstown High School, where he’s principal.

“He taught us that we could do anything,” Dawson says. “When you experience winning, when you are part of a dynasty, you want that same level of success in everything that you do. It’s transferred to my professional life. When it comes to the classroom, I’m just as competitive academically as I was on the court.”

Calvert Hall coach Mark Amatucci calls it “the best high school game ever played in Baltimore.”

His perspective is understandable.

In the 1980-81 season, his team defeated Dunbar in triple overtime before a sellout crowd at the Towson Center. “It was kind of like a Rocky movie,” Amatucci says. “The last guy standing was gonna win.”

While the loss was the last the Poets suffered for two-plus seasons, Calvert Hall (which competes in the Catholic League) fell in its season-ending tournament, held well after Dunbar’s season had concluded. Amatucci believed his team was drained from the Dunbar game.

“We go into the summer and they ranked us No. 1 in the preseason and Dunbar No. 2,” he says. “So I came out very early and said, ‘We don’t have any problem playing Dunbar, but, because of the circumstances from the previous year, I would want to do it [earlier], during the regular season.’”

But Amatucci’s phone never rang. No promoters or city officials called with an offer to stage the game.

It wasn’t until after Dunbar, with its new point guard Muggsy Bogues, travelled to New Jersey in January 1982 and defeated powerhouse Camden that public demand for a rematch with Calvert Hall intensified.

“Camden was the No. 1 team in the nation, and we [were] climbing the ranks,” Bogues says. “The crowd had never seen a guy like myself. They started laughing and giggling, but it was something that fueled me. It got me more excited. Coach came back in the huddle and asked me was I okay. I told him, ‘Hey coach, I’m fine. We gonna have a party. Let’s play basketball.’ I remember stealing the ball three times in a row, getting the game started.”

It was over in the blink of an eye, a cold-blooded assassination that captured the nation’s attention. When the Poets and buses of their followers rolled out of Camden after the 29-point win, it was clear they were returning to the city of the nation’s two elite teams.

“We get into January and it really did turn into a circus,” Amatucci says. “Promoters and the mayor and the governor all wanted to have it. Being the way I was, I was more determined than ever not to do it.”

Timing and egos conspired to prevent a rematch. If the teams were to play after Calvert Hall’s final tournament, Dunbar would have been idle for nearly a month—and clearly rusty.

“I’ll wait two weeks,” Wade told The Sun on March 1, 1982. “Any longer wouldn’t be fair to the kids.”

Each side thinks it would have starred in the sequel.

“We had a new addition to the team, that was Muggs,” says Wingate, who was taken in the second round of the 1986 draft and played 14 years in the NBA. “They probably couldn’t have even kept it close.”

“We thought very strongly that we would beat them again,” says Amatucci, whose team starred future NBA player Duane Ferrell. “They had a great team in ’82 just like we did, it was a shame we weren’t able to put it together.”

Then and now, high school national championships are primarily mythological creations of the media. Calvert Hall claims the 1982 title, Dunbar the crown for its ’83 team.

Neither one matters. Sports Illustrated summarized the situation artfully in a February 8, 1982, story headlined “Two Kings of the Hill”: “It looks as if two of the best high school teams in the country are best at ducking each other. The season may well end with the two powers bound in a tacit nonaggression pact, so both can claim to be No. 1—in Baltimore and everywhere else.”

A generation later, memories of both teams’ brilliant seasons linger. Dunbar’s legacy, boosted by its 5-foot-3 basketball giant, perhaps looms a bit larger.

As the Poets cruise to a double-digit victory over Carver, a few hundred fans watch passively from the plastic bleachers. The old wooden ones, on which thousands stomped, are long gone.

Coach Cyrus Jones played for outstanding Dunbar teams in the early ’90s, when recollections of Muggsy and the Reggies were riper. “Now that I’m the coach, I try and get my players to understand the importance of what type of history the school has,” Jones says. “I don’t know if they all realize exactly how big things were. I don’t know if we can get back to that point of where it is packed every day. Everything has changed. With the league we are now playing in, unfortunately, there are not that many competitive teams.”

Preston Jay, seated behind the home bench, understands the history well. He graduated from Dunbar in 1971, and figures he’s seen most every Poets game since 1966. While the wins keep on coming (Dunbar was 15-2 through February 6), it’s different now, he says, more matter-of-factly than wistfully.

“Back then it was the best show in town for $1. If you didn’t get in by halftime of the JV game, you didn’t get a seat. They’d stand five-deep behind the end line. Never be a team like that again.”

Bob Wade isn’t sure. “The old saying is history repeats itself,” he says. “To have four NBA players, that’s going to be difficult. I guess, eventually, down the road, someone will assemble a team that might be comparable to the one I was blessed with.”

Hanging somewhat inconspicuously on the upper left corner of the wall behind the far basket in the gym is a yellow banner honoring the 1981-1982 “Varsity Basketball City Champions.” While another conceivably could hang on its level, there’s no room for anything above it.