Sports

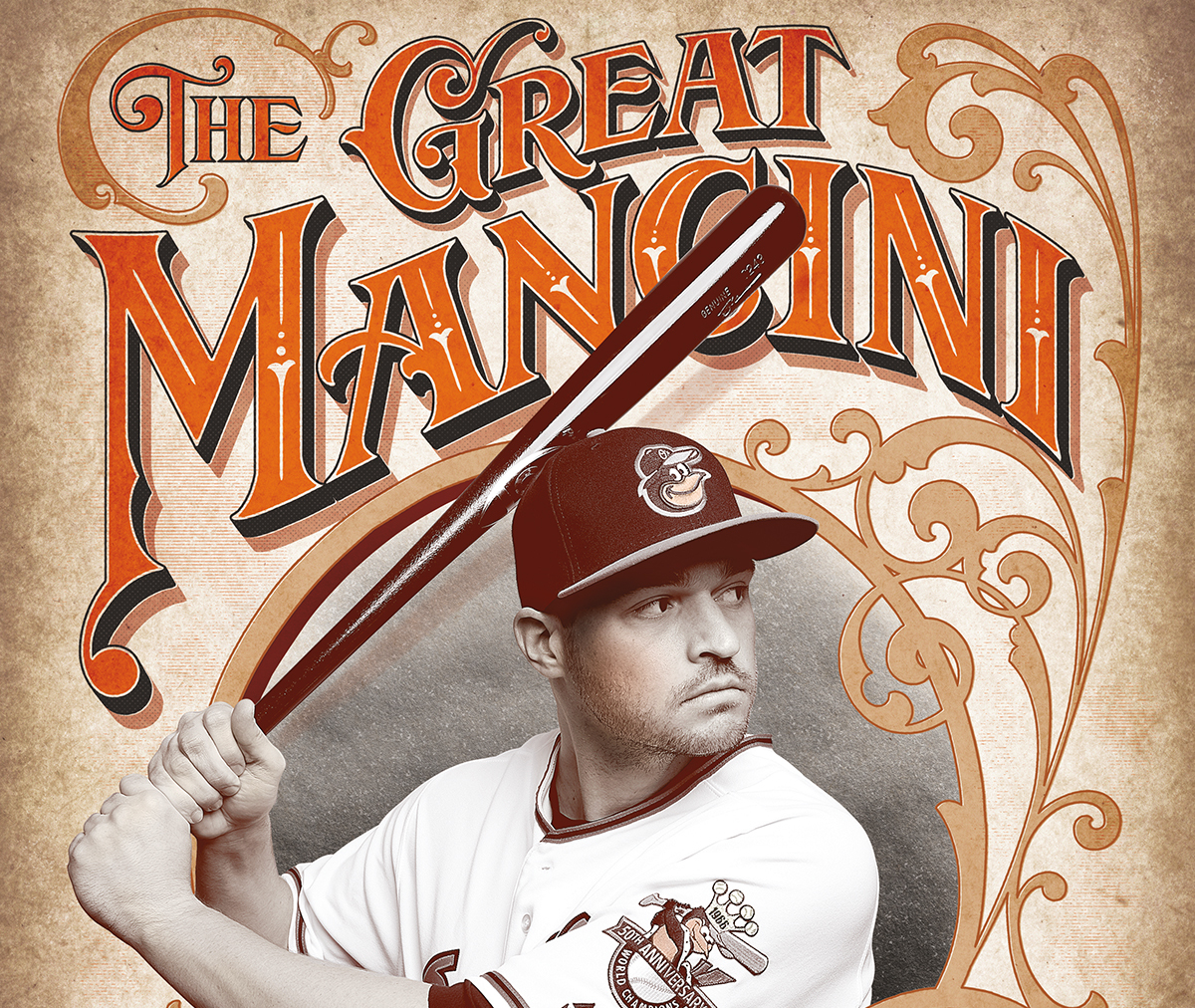

The Great Mancini

Oriole Trey Mancini talks his remarkable rookie year and making magic at the plate.

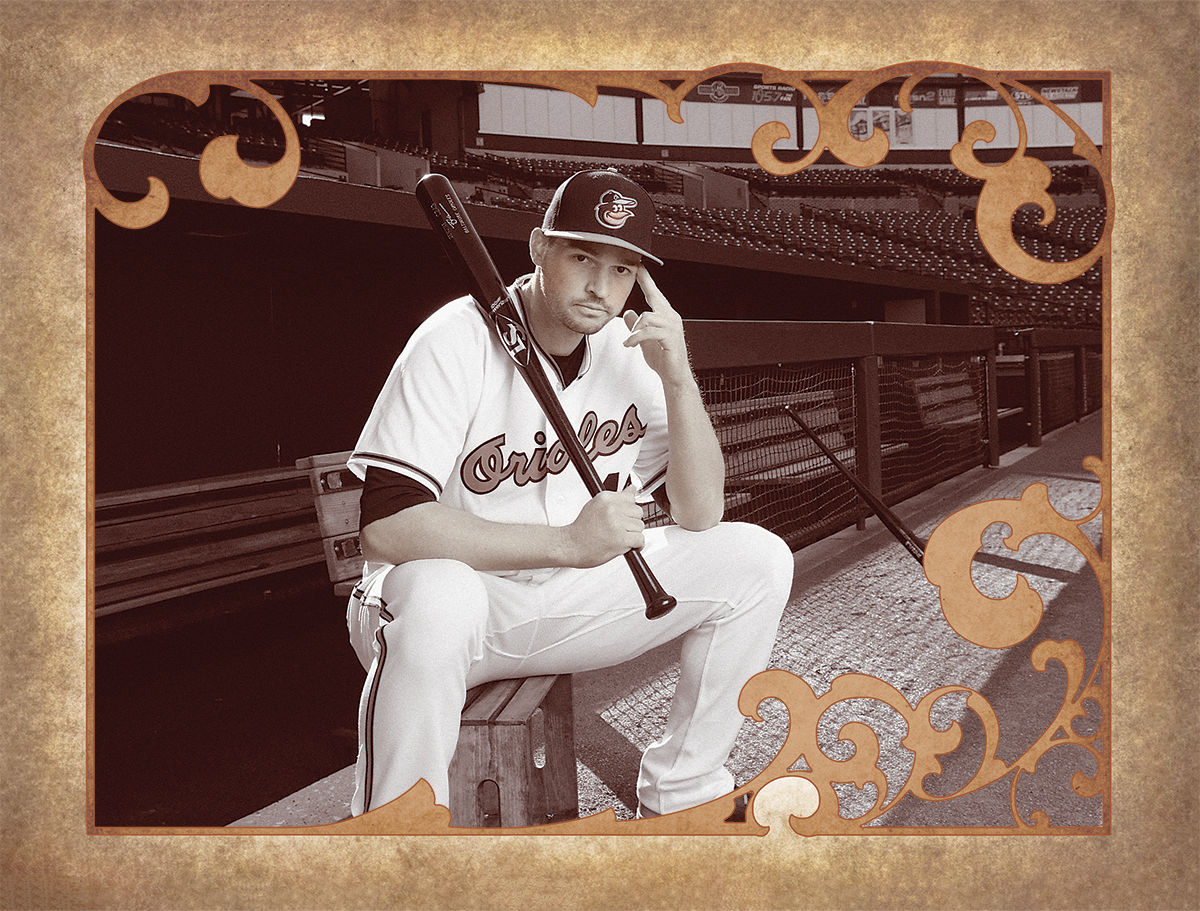

As he stood at the plate, wagging his bat in anticipation, it seemed that all the stars had aligned for right-handed hitter Trey Mancini. Just days before, he was heading to a restaurant in Florida when he got a call from Brian Graham, Orioles director of player development, and found out he was being called up to the major leagues. He was on a direct flight to Baltimore the next day, and now, here he was, up to bat in the Big Show.

As he stood at the plate, wagging his bat in anticipation, it seemed that all the stars had aligned for right-handed hitter Trey Mancini. Just days before, he was heading to a restaurant in Florida when he got a call from Brian Graham, Orioles director of player development, and found out he was being called up to the major leagues. He was on a direct flight to Baltimore the next day, and now, here he was, up to bat in the Big Show.

“It was surreal,” Mancini recalls of that first game at Camden Yards. “I had grown up in the minor leagues seeing all these guys play, and it was incredible to be on the same team.”

In the bottom of the fifth, the Orioles were down 2-0 to the Boston Red Sox when Mancini stepped into the batter’s box. His mom, Beth Mancini, and other friends and family sat in the stands. There were two outs, and on a 1-1 count, Mancini shot a cannon off of Eduardo Rodriguez into left-center field.

“I saw the ball go over the fence, but I don’t remember running the bases,” says Mancini, now 26. “I kind of went blank.”

In fact, he ran them in a flash and was greeted at the dugout by Manny Machado and Adam Jones, who had to coax the rookie into doing a curtain call for the fans. Most enthusiastic among them was his mom, who by now was furiously jumping up in the air and sobbing.

“It wasn’t just about the home run. He’s hit many,” Beth says. “It was this flashback to T-ball, all the travel we’ve done. It was 21 years.”

After the game, Mancini revealed to reporters in the clubhouse that his maternal grandfather, Mike Ryan, was a 20-year Orioles season ticket holder. It also happened to be his grandfather’s birthday; he would have been 79.

“ He’s a better guy than he is a baseball player, and he proved to the world last year that he’s one heck of a player.”

“My whole family couldn’t believe he got called up on my dad’s birthday,” says Beth, who is originally from Bowie. “All those names—Jim Palmer, Rick Dempsey—were household names growing up. I am the oldest of seven kids and, everywhere we went, that radio in the station wagon was set to an Orioles game.”

That was just the beginning. The following 2017 season, Mancini clocked 24 home runs, 78 RBIs, and earned an impressive .826 OPS, which combines on-base percentage and slugging average. He came in third in the Rookie of the Year voting—behind a superhuman Aaron Judge—and won the hearts of fans as a clutch batter and a quick study in the outfield. His 6’4” frame and long limbs have helped make him the ideal utility player.

“When I first saw him in action, it was extremely apparent that he knew what he was doing at the plate,” says Oriole Mark Trumbo. “He has an uncanny knack to square the ball up over and over again. He can run. He can hit for a high average. He’s earned his stripes every step of the way.”

Despite the made-for-TV moments at the plate, success hasn’t necessarily come easily for Mancini—and certainly didn’t happen overnight.

►Ten questions with Trey Mancini of the Baltimore Orioles.

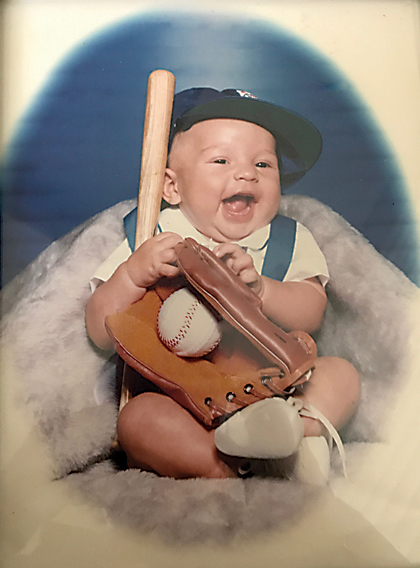

► Trey’s love of baseball began at a very early age.

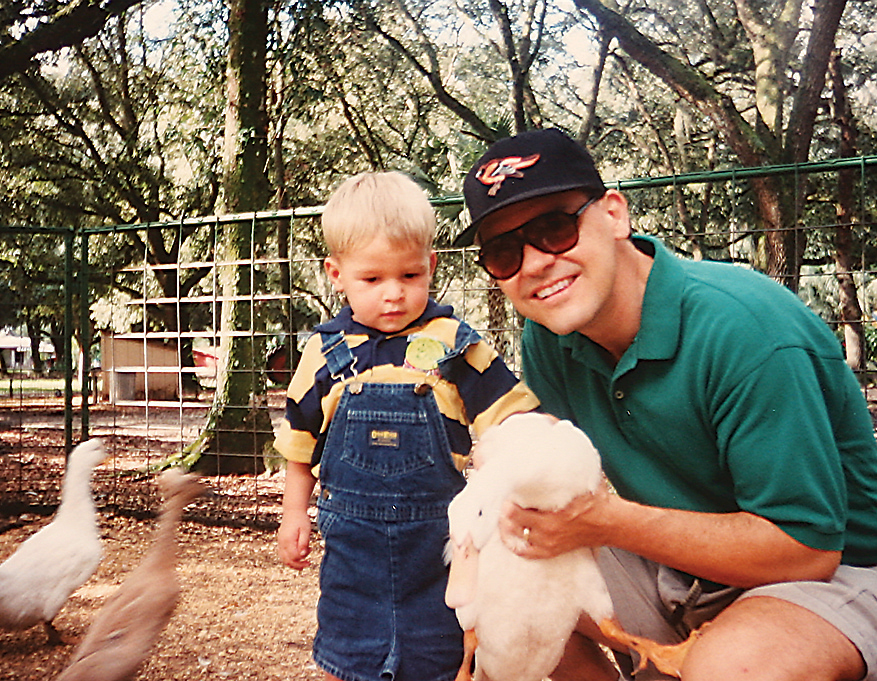

Baseball has been a priority ever since Mancini was a towheaded 3 year old growing up visiting the beaches of Longboat Key, Florida. He insisted that his dad, Tony, play catch on the white sand and, any time his dad would tire, young Mancini would have a meltdown. One evening, they even played catch for so long that Tony got dehydrated.

“I can picture him on the beach with white hair and Trey just wanted to keep on and on,” Beth says. “His passion was very intense and started very early on.”

The next year, his mom signed him up for T-ball, which might seem young, but was par for the course in Central Florida, where toddlers and their families are already thinking about high school ball.

“I struggled at first in T-ball,” says Mancini, being characteristically hard on himself. After a few years, he got the hang of it. “I remember winning a state championship, and we went to a tournament in Oklahoma, which is a long way to go when you’re 8. That was the first time I got a taste of success, and that really springboarded me into playing more seriously.”

On weekends, in his hometown of Winter Haven, Florida, Mancini would go tubing and water skiing on one of the many canal-linked Chain of Lakes. And playing tennis with his parents and two sisters was big, too. But it always came back to baseball.

“We were at the ballfield all the time,” says his older sister, Katie Pettinari. “We did our homework there, we ate dinner there. And Trey was always one of the best players of any team he was on.”

Mancini also has vague memories of going to Camden Yards with his grandfather as a kid—and specifically remembers the large brick warehouse. There were some Friday afternoons back in Florida when kids’ parents could get them out of school early to take in a 1 p.m. Cleveland Indians spring training game at Chain of Lakes Park.

“All the kids in our town would go watch the major league players and try to get autographs and all that,” he says. But he wanted more than a signed baseball. “Even though I knew I had to work hard and put the steps in, I knew looking at those players, that’s what I wanted to do.”

► Trey mancini with his dad, Tony, wearing a prophetic hat.

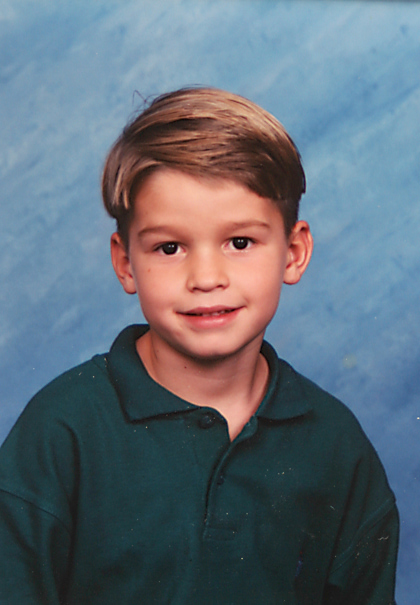

Despite—or maybe because of—Mancini’s talent and passion for the game, there was always a chip on his shoulder, which sometimes manifested in frustration and eventual teachable moments. Like when he didn’t make varsity his freshman year at Winter Haven High School.

“An unfortunate thing is you have to choke under pressure to realize how to get to know yourself,” he says. “You have to figure out how to utilize that frustration or nervous energy to your advantage.”

He eventually had an incredible senior year, hitting .481 and being ranked the 20th best player in Florida. While a lot of other kids his age were attracted to big colleges down south, he headed to Indiana after being recruited by University of Notre Dame.

“I grew up Catholic, so that’s sort of the pinnacle place you want to go,” he says. “Plus, it was the most beautiful campus I had ever seen. They really placed the importance on the academics as well as the athletics. I knew I had the potential to play professional baseball, but I also knew I might not.”

Mancini decided to study political science during his time at Notre Dame and took a justice class leading up to the 2012 presidential election that felt particularly timely with the rise of social media in politics. Meanwhile, Mancini’s first year of college happened to coincide with coach Mik Aoki’s first year heading up the Notre Dame baseball team.

“I was stupid enough not to start him in his first collegiate game,” Aoki says, admitting it’s a move he still regrets. “He really wanted to swing the bat and, initially, I had some concerns about whether that aggressiveness would translate to strikeouts.”

But Aoki said that Mancini quickly grew on him, which he credits not only to what he saw at the plate and first base, but also to the kid’s mental game.

“You’d think he would be susceptible to a slider on two strikes,” Aoki says. “But his memory bank is so impressive. He’s immediately able to process the pitches and readjust. He knows whether to lay off or smash it. Not to mention, he’s one of the best first basemen I’ve ever had.”

In college, Mancini developed crucial social relationships and camaraderie with his teammates, many of whom he still considers his best friends. There was one night after Notre Dame assistant coach Chuck Ristano’s rehearsal dinner—which happened to be on Halloween—when Mancini showed up in a Smurf costume.

“He didn’t take himself too seriously,” Aoki laughs. “His teammates and coaches, we all legitimately love him. He’s a better guy than he is a baseball player, and he proved to the world last year that he’s one heck of a player.”

Mancini played summer collegiate ball in New England for the Holyoke Blue Sox in 2011 and Harwich Mariners in 2012. When he was playing for Holyoke, the GM was Kirk Fredriksson, who ended up being a scout for the Orioles and saw him play in several games. This led the Orioles to select Mancini in the eighth round of the 2013 MLB draft—respectable, but not where the blue-chippers were selected.

► the young mancini posing for an elementary school portrait.

“To me, he was a first-round hitter, but he didn’t get taken that way,” Aoki says. “Some slight bumps in the road have been good for Trey. You look at a kid like [the Nationals’] Bryce Harper, who’s been talked about since he was 14, and the road is clear for him. I think Trey has grown and become better for having gone through the hurdles.”

The farm system wasn’t the smoothest road for Mancini either, but the gradual building blocks were an intentional move. He played for every team in the system: the IronBirds in 2013, Shorebirds in 2014, he then transferred mid-season to Frederick, was promoted the following year to Bowie, and played for Norfolk in April 2016 until he got called up to the Orioles.

“The only way to grow as a baseball player or as a person is through failure,” Beth says. “I can’t credit the Orioles coaches enough. There were two distinct times he got stuck. The coaches noticed the defeat on his face and talked him through it. He needed to grow mentally and Coach [Buck] Showalter knew he needed to go through every level in order to do that.”

Mancini came into the 2016 season while the Orioles were in a playoff hunt—and saw that as the ultimate compliment a manager could give a player. He found a mentor in Jones, quickly bonded with fellow rookie Joey Rickard, saw a lot of himself in Trumbo, and made a fast friend in locker neighbor Caleb Joseph.

“There always seemed to be a hardcore blue-collar mentality associated with putting on an Orioles uniform—and that’s what Trey embodies,” Joseph says. “He just wants the Orioles to win. If we had 25 Treys, I’d feel really good about going to battle every day.”

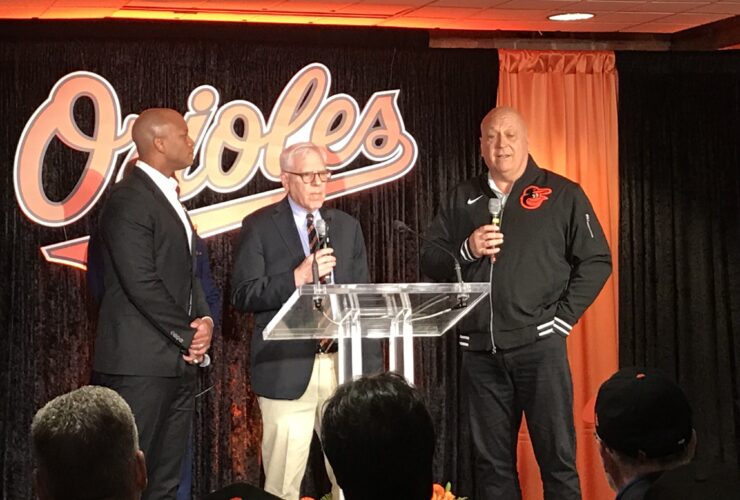

►TREY mancini at camden yards in january.

The pressure was on Mancini, yet again, in early June of 2017. With the hometown team trailing the Pittsburgh Pirates 6-2 in the ninth, many of the Orioles faithful had cleared out of their seats in Camden Yards. But the O’s managed to put runners on the corners, Rickard hit a sac fly and J.J. Hardy hit a double, cutting the lead in half. With two outs looming, Mancini pinch-hit for Seth Smith.

“It was a nerve-wracking situation,” Mancini remembers. “I didn’t want to lose all that momentum. I got up there, took a deep breath, and tried not to make the situation any bigger than it was. Nothing else in the world matters except you and the pitcher.”

Pirates closer Tony Watson delivered eight pitches during that at-bat, two of which were sliders that nearly hit Mancini.

“After that, I stepped out of the batter’s box and thought, ‘Okay, dude, you need to focus’ and totally reset myself,” he recalls. “I’ve done some yoga and I know that breathing is really important in baseball.”

Mancini took several deep breaths. Four seconds in, four out. Four seconds in, eight out. Four seconds in, 12 out. He stepped back in, adjusted his batting helmet, and proceeded to get every piece of Watson’s change-up for a two-run bomb over the right-field fence. Two innings later, Mancini hit a three-run, walk-off home run to seal the Orioles’ 9-6 victory.

“I came in ready to hit,” he told reporters after the game. “Baseball is the game where you never know what can happen.”

Those unpredictable yet serendipitous moments came to define Mancini’s 2017 season, and much of what’s been written about him focuses on those miraculous at-bats. But probably even more impressive is what he was able to accomplish in the field.

There was his incredible work in left field, a position he had little to no experience with before the year started. He made SportsCenter-worthy catches out there and says he even enjoyed hearing some of the heckling from the fans. This past January, MLB Network named him one of the 10 best left fielders in the league.

“He just wants the Orioles to win. If we had 25 Treys, I’d feel really good about going to battle every day.”

“When he first started playing left field, I was really impressed,” Pettinari says. “You have to remember he was learning that position in front of everybody. A lot of media and articles have labeled him as ‘non-athletic,’ which we saw couldn’t be further from the truth.”

Mancini also filled in for Chris Davis at first base while the slugger was out for nearly a month with an oblique injury.

“He reminds me of myself in a lot of ways,” Trumbo says. “I had to carve my way in as a utility first baseman, whatever’s needed. He’s done it the same way. Trey embodies what a younger rookie should do. He listens before he speaks.”

Though he may have been an ideal first-year player for the Orioles, the Rookie of the Year title eluded Mancini, who came in third behind Red Sox outfielder Andrew Benintendi and the Yankees’ Aaron Judge, whose stats blew everyone else’s out of the water.

“I grew up playing with Aaron in the minors, and he’s one of the nicest people I’ve met in my life,” Mancini says. “I don’t think it’s too bold of a statement to say he’s the most deserving Rookie of the Year of all time. He has no glaring weaknesses.” (Though Mancini said he might be able to take him in tennis: “But, knowing Aaron, he’s probably really good at that, too.”)

Losing out on these sorts of accolades is something Mancini takes in stride, even when it’s simply about pie. Due to some lousy timing—the Orioles banned the post-game tradition of celebratory pies to the face (for safety concerns)—Mancini never got pied despite many opportunities. “I’ve always wanted one,” he says. “Mainly because it just looks delicious!”

Aside from excelling on the field, Mancini spent most of the 2017 season getting to know his teammates, as well as exploring Washington D.C. and Baltimore. He enjoys tacos from Barcocina and big brunches at Miss Shirley’s Café and Iron Rooster. Family is a huge priority for Mancini, and being an uncle to Pettinari’s two sons, Gianluca and Mimmo, has been a recent highlight.

“Trey is very overprotective,” Pettinari says. “I remember when my second son was born, he drove like 15 miles per hour to the hospital. It’s very sweet.”

There is also a big nerdy side to the baseball player, who counts Harry Potter as one of his personal interests. “Not to toot my own horn, but I think I would be a Gryffindor,” he says of the house in J.K. Rowling’s universe known for its bravery and loyalty.

“He’s a huge Game of Thrones fan, almost to a dorky level,” Trumbo says. “He was heavy into online spoilers, and I told him to keep those to himself. I think he’s probably got quite a few quirks that the guys aren’t aware of.”

The rest of the Orioles will surely find out more about those eccentricities, as many players agree that Mancini is a vital part of the team’s future. Whether diving for balls in the outfield or swinging for the fences during extra innings, he has earned a firm place in Baltimore.

“He has willed himself into that lineup, into that outfield, and into the top three rookie spot,” Joseph says. “You can’t say enough about that fire. Sadly, more and more players these days are out for personal fame and fortune. He’ll receive that because he’s a good player. But that’s not his motivation. It’s refreshing.”

With slight setbacks every step of the way, Mancini is going into 2018 with a positive attitude and inherent knowledge that nothing is ever handed to you.

“Every spring training, I’ve gone in with the mindset that I’m fighting for a job,” he says. “I came to love it in the outfield, and I’m working on my jumps out there. I’d give myself a B or maybe B+ right now. I’m not going to give myself an A.”