Education & Family

Through Their Eyes

In 1954, the Supreme Court declared segregated education unconstitutional. Sixty years later, four Baltimoreans recall their first days in their new schools.

“Inherently unequal” was the phrase Earl Warren used, writing his first major opinion as Supreme Court chief justice on May 17, 1954,striking down the “separate but equal” principle that long-governed American public education.

To separate black children in schools, Warren said, “from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to theirstatus in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone.”

Oliver Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas was brought by the father of a third-grade girl forced to ride a bus to a “colored” school rather than be allowed to walk to a closer—and better—white elementary school. It’s not unlike the childhood experience of Carolyn Holland Cole, raised near Pimlico, who shares her story in the ensuing pages. The NAACP’s lead attorney representing Brown before the Supreme Court was Thurgood Marshall, an alumnus of Baltimore’s Frederick Douglass High School, who had spent two decades fighting and winning significant civil-rights and education legal battles—including several in Maryland that set the stage for the 1954 landmark desegregation victory.

After the court’s decision, the city’s school board, led by new president Walter Sondheim Jr., acted quickly. With lawsuits to desegregate Western and Mergenthaler Vocational-Technical high schools already working through the legal system, the Board approved a policy on June 10, 1954 “removing the race of pupil” from school admission consideration. Baltimore became one of the first U.S. cities to desegregate its schools—although much of the state would lag behind until after the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

While hopes of an integrated city school system disappeared as whites fled to the suburbs and private schools, it’s worth noting the impact of desegregation only a few generations later in nearby districts. Baltimore County public schools, with a 39 percent African-American population, and Howard County public schools, with a 21 percent African-American student population, for example, today are considered among the better large school districts in the country.

“Sometimes I think how odd it must be for those people who fled Edmonson Village, which used to be all white, escaping to Ellicott City,” says Keiffer Mitchell Sr., who also shares his story here. “Now, many of those schools that their grandchildren—who have so many diverse friends—are attending in Howard County are more integrated than they ever would’ve imagined.”

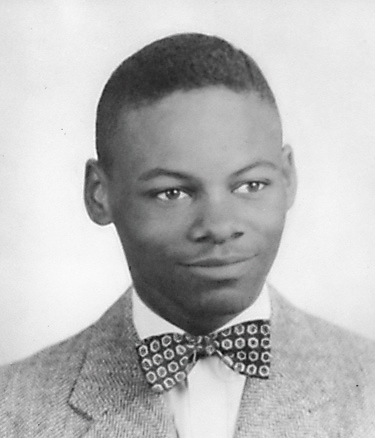

Milton Cornish, 75

Polytechnic Institute, 1952

“I went through elementary and middle schools that were segregated, just like the city itself. There were 16 of us selected, all strong math students, to go to Poly for ninth or 10th grade in 1952—two years before the Brown decision—and that was really a change, of course, for all of us to go to a white school. The Urban League and the NAACP attorneys, including Thurgood Marshall, had argued before the city’s school board there wasn’t anything comparable to Poly’s ‘A’-course curriculum in the black schools. I hadn’t really been aware of who Thurgood Marshall was, but I was mesmerized when he spoke before the school board. I’d gone to P.S. 103/Henry Highland Garnet Elementary School, which I later learned was where he went to school.

“I went through elementary and middle schools that were segregated, just like the city itself. There were 16 of us selected, all strong math students, to go to Poly for ninth or 10th grade in 1952—two years before the Brown decision—and that was really a change, of course, for all of us to go to a white school. The Urban League and the NAACP attorneys, including Thurgood Marshall, had argued before the city’s school board there wasn’t anything comparable to Poly’s ‘A’-course curriculum in the black schools. I hadn’t really been aware of who Thurgood Marshall was, but I was mesmerized when he spoke before the school board. I’d gone to P.S. 103/Henry Highland Garnet Elementary School, which I later learned was where he went to school.

My dad was a porter and my mother was a nurse’s aide, and we met several times with Furman Templeton [former Baltimore Urban League director] that summer. Everyone considered for Poly did. My parents saw it as an opportunity for me to have a different kind of education.

I was so overwhelmed the first year. There were three huge buildings—Poly used to be on North Avenue where school administration headquarters are now. I was excited, fearful, just trying to find my way to class. You got stared at, but it felt more like curiosity than hostility. Dr. Wilmer DeHuff, the school’s principal, had been against us coming, which we knew. Once we were there, though, it meant we’d go out into the world as ‘Poly Boys’ and Dr. DeHuff made sure that we would uphold that standard. There was a lot of pressure on us—and I mean academically. I went to school, and, when I came home, I did homework for three or four hours. In my neighborhood, people would often ask, ‘How are you managing?,’ and I’d always say ‘Fine,’ but in my mind I wasn’t so sure I was going to make it.

I don’t remember ever hearing the ‘N’ word or anything like that inside Poly. Most of us played sports and maybe you heard it when you played another school, but you never know what to make of that—could just be boys being boys. Most white people didn’t know we were there until 1954, when there was a protest in front of the school. Then Dr. DeHuff made an announcement that any Poly students not in their seats for first period would be expelled and that ended that.

Really, it was a great experience for me. The benefits have lasted a lifetime. The only downside was socially. We didn’t attend any of the ‘Blue & Orange’ dances and you weren’t friends with students outside of school. I spent 36 years in the Army Corps of Engineers, retiring as chief of emergency management for the Baltimore district, and only later, working with the Corps of Engineers, did I form long-lasting friendships with a number of guys I’d gone to Poly with years before.”

Carolyn Holland Cole, 68

Arlington Elementary School, 1954

“I can still remember my fourth-grade teacher, Mrs. Bissinger, and the principal, Mrs. Frank, from Arlington.

“I can still remember my fourth-grade teacher, Mrs. Bissinger, and the principal, Mrs. Frank, from Arlington.

I was coming from a little two-room schoolhouse on Denmore Avenue, they called it P.S. 157, and it was the only school African-American kids could go to, and there was no kindergarten. There were six grades crowded into that schoolhouse; one teacher taught grades one through three in one room and the other taught grades four through six in the other. The books were all handed down from the white schools. But that school was a real pillar of the community. My mother was a PTA member and the teacher in charge would occasionally come over for dinner.

To go to Arlington Elementary, the white school, which was closer to my house, that was only a dream. I used to go to the school’s playground over the summer and peek in the windows. They actually had a school library, gym, and cafeteria. It looked like utopia to me. In the summer of 1954, I was visiting family in West Virginia with my mother when my father—he’d been a pretty well known jockey—and my older brother decided I should go to Arlington for fourth grade. My father had seen me looking in the school windows and he knew how much I wanted to go there. But as a nine year old, you also had seen the images on TV of students being attacked by dogs and sprayed with fire hoses and I was frightened at the same time.

My mother came to school with me the first day, and I remember Mrs. Frank greeting everyone and telling my mom that they were going to put another little black boy in my class so I wouldn’t be alone. I wore a brand new dress and had my hair in long ponytails and when I walked into the classroom, Mrs. Bissinger said, ‘Well, aren’t you a pretty little girl.’ All my worries just left me at that moment.

When I was at the two-room school, I was tops in my grade in everything, but at Arlington they were about a grade ahead and some of the math we’d never had—though I didn’t reveal that to anyone at the school. When I came home, I told my brother, ‘They’re doing long division that I don’t know how to do,’ and he helped me. And I joined the glee club, even though I couldn’t sing. Of course, we didn’t have a glee club or a drama club or anything like that at my old school.

From there, I went to Pimlico Junior High; we lived only a few blocks away. They had an accelerated program and I met some other African-American girls—very pretty girls and smart—who’d come from the Gwynns Falls area. That school was probably 92-percent Jewish. Jewish people had a whole different way of thinking [about desegregation], and we were warmly embraced. I graduated from Forest Park High School in 1963, went to college, and then served 41 years in the city school system— twenty years as a teacher, and then I went into administration. I was a principal first at Frederick Elementary, a school we turned around, and then principal at Roland Park Elementary/Middle, where I retired in 2012.

I consider Arlington Elementary to be the place where my first-class education began.”

Edna Jackson Greer, 67

Woodbourne Junior High, 1957

My mother was vice principal at Fanny L. Barbour in West Baltimore, which is where I went. My mother is a story by herself. Her grandmother had been a slave. She’d gone to school in a one-room schoolhouse in Sykesville, but there wasn’t a black high school there, and she rode the train every morning into Camden Station and then walked to Frederick Douglass, which was then near North Avenue. To earn her master’s degree, she took a weekend train to New York University.

In seventh grade, after I finished elementary school, I went to Woodbourne Junior High. I thought I was very fortunate; we all knew the white schools had better facilities. It was the closest to my house, and I could walk, but all the feeder schools were white. It was a shock. I started there in 1957 and was the only black student in my class, and I suffered a lot of problems that first year. The teachers were nice, but the kids called me names, and I cried every day. I also became ashamed because I was dark brown-skinned, and, in those days, the lighter you were, the more you were considered good-looking and accepted. And I remember Mr. Walpert, our social-studies teacher, showing a filmstrip about slavery in class and just wanting to slink down and hide in my chair. The boys called me ‘pickaninny’ and ‘Aunt Jemima.’

But I had felt very good about myself before going to school there. I’d done poetry readings at my old school and played the piano, and my mother and father knew, I think, that I’d build my self-esteem back up. Eventually, I played piano with the choir and earned some recognition, especially when we visited other schools, and that helped me become more accepted. Education was very important in our home, and it was tough that first year, making the transition. I remember my father, even if there was a program he wanted to watch, turning the TV off in the evenings so there’d be nothing but peace and quiet in the house.

I did have girlfriends in school—girls whose names I remember to this day—but you didn’t see the kids outside of school. There were separate African-American churches and Girl Scout troops. There was no social integration. In a lot of ways, that hasn’t changed, which is too bad.

After Woodbourne, I went to Eastern High School, which was segregated in a different way—all girls—and then Morgan. I earned my master’s and advanced certification in education from Hopkins. In 1986, I became the first African-American principal at Mount Washington Elementary School. I became principal here at Leith Walk 23 years ago. Woodbourne, which has been renamed several times, is a couple of blocks away. It’s like I’ve come full circle.

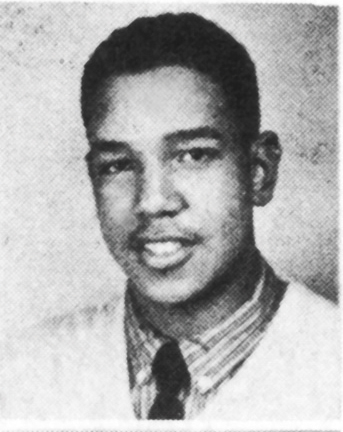

Dr. Keiffer Mitchell Sr., 72

Gwynns Falls Park Junior High School, 1954

“I’d been at Booker T. Washington Junior High School and after the Brown decision, my parents spoke to me of the greater resources at Gwynns Falls Park Junior High, particularly because of my art ability. The black schools didn’t have equal supplies as the white schools, and, later, I did win a citywide art competition. I’d also created a woodblock print my first year at Gwynns Falls Park that made the cover of the school newspaper—just three kids in harmony looking at a store window with their backs toward the viewer. But you couldn’t tell what race they were. Only guess.

“I’d been at Booker T. Washington Junior High School and after the Brown decision, my parents spoke to me of the greater resources at Gwynns Falls Park Junior High, particularly because of my art ability. The black schools didn’t have equal supplies as the white schools, and, later, I did win a citywide art competition. I’d also created a woodblock print my first year at Gwynns Falls Park that made the cover of the school newspaper—just three kids in harmony looking at a store window with their backs toward the viewer. But you couldn’t tell what race they were. Only guess.

My father, Clarence Mitchell Jr. [NAACP chief lobbyist for nearly 30 years and in whose honor the Baltimore City Courthouse is named], and mother, Juanita Jackson Mitchell, who became the first black woman to practice law in Maryland, were revolutionaries in the battle against apartheid. And my grandmother, Lillie May Jackson, led the Baltimore Branch of the NAACP for 35 years. When I was growing up, Thurgood Marshall and Charles Hamilton Houston, who was Thurgood Marshall’s mentor, sat in our living room plotting legal strategy. It was my older brother’s job and mine to serve the tuna fish sandwiches. A couple of years later, in 1956, my parents entertained Hungarian freedom fighters in our home.

Booker T. was very overcrowded and my parents went to one of the school’s PTA meetings to encourage parents to send their children to the ‘white’ schools. But, by design, they were ‘hooted’ out of the meeting. Some parents felt they were going to lose their local schools. There was conjecture, too, that black teachers were afraid that desegregation meant they’d lose their jobs. The black schools were run as a completely separate school system, had their own school headquarters, and there was so much uncertainity at the time. As a result, I had to face some hostility from neighborhood residents—and then hostility at Gwynns Falls Park, too. I was beaten up one day by a group of older white teenage toughs on the school’s playground after breaking the school’s color barrier. It got so bad that I walked a gauntlet from the bus stop to the school. Once inside, I hid away in the art department. My father saw what was going on and walked a one-man picket line in front of the school, holding up a sign that read, ‘I Am An American, Too.’

If I’d known then that my son [Del. Keiffer Mitchell Jr.] would later represent that district in the City Council for 12 years, it might have strengthened my resolve.

Thankfully, I was only there two years and then went to City College [more gracefully integrated], where I played football and graduated in 1959. But the city was still segregated. I remember going to a luncheonette with my teammates at 33rd and Alameda after practice, trying to get something cool to drink and having to stand up while they sat down. I attended Morgan State before transferring to Lincoln University and then studied medicine at Meharry Medical College in Nashville, TN. I still practice today.”