Home & Living

An Old Salt Comes Home

The National Aquarium, Baltimore, CEO and a California native, John Racanelli is no fish out of water in his Canton home.

The first time that National Aquarium, Baltimore chief executive officer John Racanelli visited Baltimore, he was 20 and on board The Explorer, one of a fleet of tall ships sailing to the Inner Harbor as part of the nation’s 1976 bicentennial celebration. “The ship had been built in 1904 and was the official tall ship of Washington and Oregon,” recalls Racanelli. “It had sailed around Cape Horn and charted the waters of Alaska and the Puget Sound for decades before being restored. It was not a beautiful ship—we called ourselves ‘The Bicentennial Pirate Ship.’”

At the time, the lifelong sailor, who was the navigator from Costa Rica to Baltimore, coincidentally pulled into port on Pier 3 where the aquarium is now situated. “Back then, I needed some life skills in addition to my schooling,” explains Racanelli, who took a leave of absence from the University of California, “so I took excursions away from school for a while, the first of which was this sailing trip on a small boat where I worked as a crewmember and sailed down the coast of Costa Rica.”

While in Costa Rica, the young seaman met the captain of The Explorer. “I went down to the ship, and a lot of people were getting off because they’d been at sea for 37 days,” says Racanelli. Among those who disembarked was the ship’s navigator. “The captain asked me, ‘Can you celestial navigate?’ Back then, I knew enough to say ‘yes,’ and he said, ‘Okay, then you can be our navigator.’ I studied everything I could. It turned out that there was a beautiful bronze sextant with a chronograph and the almanacs and all the things I needed to get from there to here.”

Racanelli recalls that Charm City was a lot less charming when he first arrived in 1976. “At the time, Pier 3 was just a flat pier,” he says. “The Inner Harbor was still very much a working harbor, and the aquarium hadn’t even been built. When people hear I spent a lot of time on the waterfront, they say, ‘Wow, back then it was pretty rough—old bars and sailors.’ And I say, ‘Well, I was one of those sailors in one of those bars. What’s the issue?’”

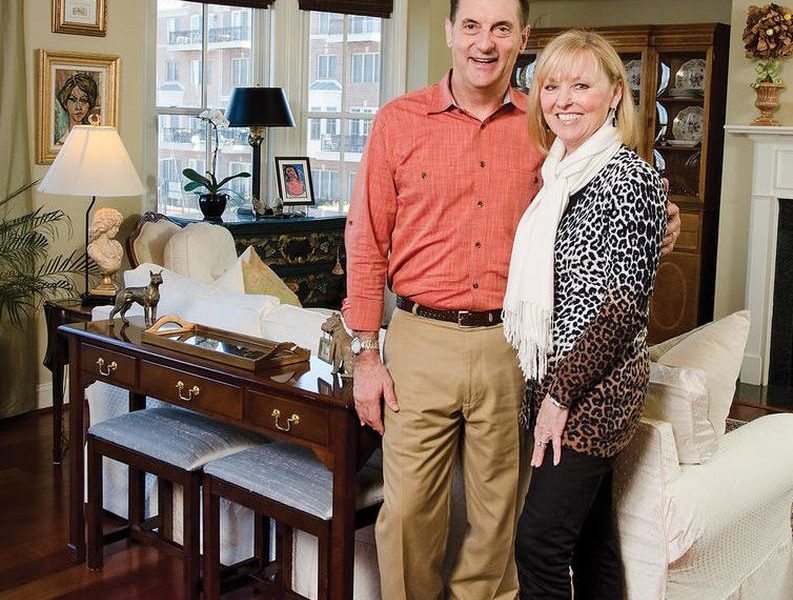

The salt spray long washed away, Racanelli now sits on the polished-cotton living-room sofa in the Canton townhome where he moved with his wife, Susan, in 2011. Despite being longtime Californians (who most recently lived in the hills of suburban San Francisco’s picturesque Marin County), Racanelli and Susan love living in Canton.

Through the years, Racanelli had visited Baltimore on several occasions, most memorably when he was on a reconnaissance mission as vice president of marketing and development with the Monterey Bay Aquarium and ended up on a V.I.P. tour of the National Aquarium (along with Liberace and his longtime boyfriend, Scott Thorson). But it wasn’t until he came back to interview for the aquarium job that he found himself truly smitten with Baltimore.

“When I came here for my second round of interviews, we spent the weekend,” says Racanelli. “We went for brunch to Mr. Rain’s Fun House and got the best Bloody Marys we’ve ever had, and we enjoyed AVAM [American Visionary Art Museum]. We went to Annapolis for dinner, found our way through Fells Point, and walked around the Inner Harbor. A lot of the things that we loved about San Francisco—the food scene, the arts, and culture—we also liked about Baltimore.”

Of course, Racanelli notes that one of the biggest differences between the two cities is the affordable housing market in Baltimore.

“We never could have had this much space in San Francisco,” says Racanelli. His current home includes three bedrooms and four and a half baths in 3,700 square feet that serves as a repository for a lifetime of collected furniture, art, and artifacts from 27 years of marriage and world travel. And as much as Racanelli appreciates all the room to spread out, he happily defers to Susan in the décor department. “I am a willing student of the vision of Susan Racanelli when it comes to home decoration,” he says with a laugh. Chimes in Susan, who works for Seacology, an international environmental organization that preserves island habitats all over the world, “I have a French-Northern Italian aesthetic, but we travel so much, I didn’t want only one thumbprint. Much of our home is a collection of all the places we’ve been.”

On the first level alone, the media room boasts a hand-carved chess set and hand-beaded candelabra from Nairobi, Kenya, as well as a pounded tapa cloth from Samoa, coasters from Uganda, a tin lizard sculpture from Madagascar, a pair of ostrich eggs from Tanzania, and a handmade Berber rug from a desert trek through Morocco. The second level, where the kitchen, living room, and dining area are located, features brightly colored pottery from Italy and Mexico, an alabaster Buddha head from Vietnam, and a pair of nesting tables from Florence, Italy. The third-floor décor includes a few stateside touches with an alligator head purchased from Miccosukee Indians in Florida (and now on display in the room of their son, Pierson, who is a senior at Cornell University) and a blanket chest from Susan’s childhood spent in Michigan. The top floor is a paean to the family—with photos of grandparents, parents, stepsiblings, and a dramatic snapshot of Yaka the Killer Whale retrieving a mackerel from Racanelli’s mouth on his last day of work at northern California’s Marine World in the early 1980s. Not surprisingly, also on display is a school of various crystal fish. “People are always giving me fishy things,” says Racanelli with a laugh.

“They’re pretty, so I don’t get upset, but I don’t know where to put them all.”

Though Susan was in charge of interior design, Racanelli did have one rule: “There’s a place for everything, and everything in its place,” he states. “And Susan has no problem with going along with that. It’s a sailor saying, ‘When you need something on a boat, you need to know where it is supposed to be.’ The same rule applies in a home, especially in a home with all these stairs and where we’re often yelling to each other from the top floor.” (Jokes Susan, “I usually just yell, ‘Ahoy, mate.’”)

Another edict was to have a more traditional-style home. “I grew up in an Eichler house,” he says of the iconic, mid-century modern tract-style housing built by real-estate developer Joseph Eichler. “Now, these are the hipster houses—all glass, wood, and steel with a flat roof. I didn’t like that house—it had a radiant-heated floor, but the pipes were galvanized so you had three or four patches in the whole house where the heat came up. As a kid, I’d lay on the floor like a cat, holding onto those patches of warmth.”

Racanelli’s favorite features of his Canton home include three decks, a patio, and commanding views of the water. “I love coming home—it’s such a refuge,” says Racanelli. “The outdoors is welcomed in here—that’s a very California thing. Being in a home that’s really comfortable for me near the water is a form of renewal and rejuvenation.”

Besides his uninvited collection of fishy bric-a-brac, people also assume he has the live kind, too. “People always ask me if I have an aquarium at home,” he says, “and I say I have this big aquarium right outside of my window.”

Living on the water also keeps his mission—both personal and professional—in the forefront. “Every time I walk down the [waterfront] promenade outside, I think, ‘We’re going to make that promenade healthy,’” says Racanelli. “Every time it rains and Harris Creek fills up with plastic water bottles, I think, ‘I have to make it my mission to help fix that—this can’t be the case in 10 years.’”

To that end, Racanelli says that the next stage for the aquarium is to focus on local exhibits in the hopes of hitting home with its 1.3 million visitors a year. “We are going to spend the next few years remaking the exhibits that are about the Chesapeake and the Atlantic Shore,” says Racanelli, who oversaw the new, $12.6 million Blacktip Reef exhibit from conception to completion last year. “The next big step is to not only show off our own backyard, but how we can be better engaged in taking care of it. We have this little window of time to get through to people that there are real threats to our planet and our oceans and all of our aquatic systems,” he says, his voice straining. “We all have to be part of the solution.”

Racanelli comes by his love of all things aquatic—scuba diving, sailing, surfing, and open-water swimming—honestly. “When I was a kid, we’d pile in the station wagon and go to this great beach town called Santa Cruz,” he remembers. “The water was frigid there, but I didn’t know any better, and I’d spend all day in it. There’s some genetic twist-up in my makeup because I’m as comfortable in the water as I am in the air.”

From an early age, it was clear that Racanelli, who has competed in swimming races in the treacherous waters surrounding Alcatraz Island, was destined to work on the water. (He’s also twice swum the length of the Golden Gate Bridge.) He first studied marine biology at the University of California, San Diego, but quickly transferred to the less competitive Santa Cruz campus. “Their mascot is the banana slug,” says Racanelli laughing. “It was counterculture. If you didn’t like the class, you could just drop it and there was no record you’d ever taken it, and thus, no incentive to try harder—this was the ’70s. So I majored in surf with a minor in environmental studies.”

Though Racanelli enjoyed tremendous professional success, including his stint as first-ever vice president of marketing and development at the Monterey Bay Aquarium, serving as the first CEO of The Florida Aquarium in Tampa, and founding his own consulting firm with a focus on cultural and conservation organizations, he accomplished it all without a formal degree. “It took me decades to finish college,” says Racanelli, who finally graduated in 2006 from Dominican University of California with a degree in strategic management. “It was unfinished business, and I wanted to get a degree before my son did.”

The sheepskin is just another emblem of how Racanelli has come full circle in his life. Not long ago, while hanging a small photograph of The Explorer on the first floor of his home, Racanelli was reminded of the ship’s own story. “I had taped a flyer to the back of that photo,” he says. “And it explains that the ship was built in Fells Point and was coming home to Baltimore when we sailed it here. There’s a nice synergy there,” he says smiling. “I feel like I’m exactly where I’m supposed to be in my life.”