Food & Drink

Soup of the Day

The slurping scene comes to Baltimore.

A symphony of slurping is in full force at Ejji. It’s lunchtime at the Belvedere Square Market ramen shop, and all six stools at the countertop are occupied by hard-core devotees of the ramen revolution. They’re scooping slices of roasted pork belly and springy noodles with chopsticks, inhaling rich broth from wooden ladles, and generally eating with abandon. And they’re not being quiet about it.

Nine miles south, a similar scene unfolds inside the nondescript food court at Charles Towers, where the favored choice is Vietnamese pho from the Mekong Delta restaurant. Somehow, even on an 88-degree May Saturday in a city not exactly known for its adventurous tastes, people are pining for a hot bowl of Asian noodle soup.

“Culturally, it’s an indicator that Baltimore’s scene is getting more advanced in terms of flavor palate,” says Phil Han, owner of Dooby’s in Mt. Vernon, which serves ramen. “Ten years ago, I think ramen here would have been a complete bust, but now you’re finding this awesome foodie audience in town that is supporting things like The Emporiyum food festival. Ramen just happens to be an element of that bigger scene.”

Luan Nguyen and his wife, Tuyen Vo, opened Mekong Delta in a small Saratoga Street row house in 2009 before relocating five years later. Its popularity has not waned despite an uptick in restaurants serving pho and the even more recent arrival of ramen on the noodle scene. “People have found out that [pho] has so many nutrients—it’s good for their health,” says Nguyen. “I often see people who don’t want to give up their bowl. They drink everything until you see the pepper on the bottom. It’s a good sign.”

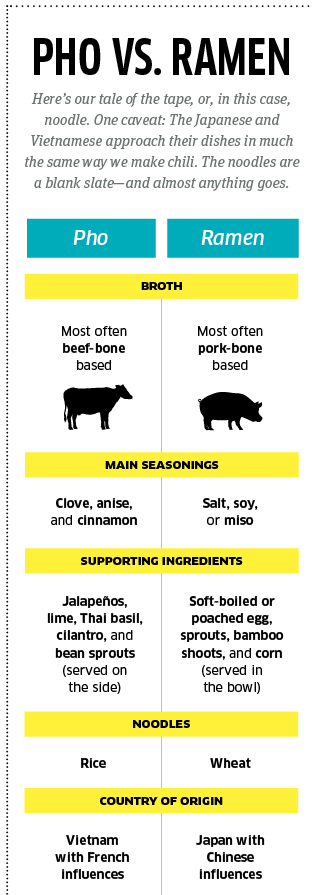

For Aaron Larrimore, pho—generally made with beef-bone-based broth, beef or chicken, and rice noodles—was his gateway drug to ramen, which is usually pork-based with wheat noodles. “I don’t know why I love eating ramen, I just do,” says the Bolton Hill resident and Dooby’s regular. “I love it because it’s a great mix of ingredients and the flavor is amazing. I never say no to it.”

He’s not alone. Mt. Washington resident Gina Bruno is perched atop a stool at Ejji, which opened last October. “It’s like nothing I’ve tasted before,” she says between slurps. “I like the texture of the noodles and I really love the miso [broth]. It’s comforting and filling and delicious. It’s so good it doesn’t even matter how hot [the weather is].”

These days, pho is associated purely with Vietnam, while ramen is considered an export of Japan. Truthfully, neither country can claim exclusive rights to its (unofficial) national noodle dish. The origins of pho, like many cuisines around the world, are mired in geopolitics. “Given our history with the Chinese going back thousands of years, of course we had noodles,” says Cuong Huynh, a San Diego-based blogger, who runs the website LovingPho.com. “Because of where [Vietnam is] in Southeast Asia, we have a lot of rice instead of wheat, so we use rice noodles. If you look at Asian cuisines, a noodle dish is a meal in itself. So a noodle dish like pho is rarely just a course in a meal; it is the meal. In Vietnam’s culinary history, we probably had something similar to pho in one form or another, but it is believed that not until the French came over did we start to make beef broth with such technique as done in pho.”

Pho—pronounced “fuh,” not “foe”—is made with a lighter broth in the north of the country, as opposed to a darker and sweeter one in the south.

Ramen also can trace its roots to China. It is believed to have arrived in Japan with Chinese tradesmen around the turn of the 20th century. Prepared in multiple ways in different regions of Japan, the bedrock of ramen soup is the noodle, made with wheat flour, water, and kansui, an alkaline mineral-rich water that gives it its yellow color and springy texture.

Despite their similarities, each found a different path to popularity in the United States. Ramen was popularized here in its instant form. Beloved for its ease of preparation and mind-bogglingly low cost, you’d be hard-pressed to find a former college student who doesn’t (usually fondly) recall capping a night of partying by devouring a bowl of ramen noodle soup in a dorm room. Its rise from penny-saving pantry filler (remarkably, a six-pack can still be bought for a buck) to the main attraction at New York hotspots like Ippudo and Momofuku is less clear. But if anyone knows, George Solt does. An assistant history professor at New York University, he completed his doctorate in the history of modern Japan at the University of California, San Diego. His dissertation was entitled, “Taking Ramen Seriously: Food, Labor, and Everyday Life in Modern Japan.” “Sushi became the representative food of Japan in the 1980s abroad, when Japan was a major business competitor to the U.S.,” he told The New Yorker in 2014. “The whole embrace of Japanese popular culture in the last 10 years is because Japan is no longer an economic threat. That image got transposed to China. It used to be Japan’s burden.”

Pho arrived in the U.S. in the same manner much of our ethnic food did—with the influx of immigrants. “Vietnamese refugees came to the U.S. in waves that stretched over almost two decades,” says Lovingpho.com’s Huynh, who was among the first to arrive here after the end of the Vietnam War in 1975. “The first wave, like us, we came over and basically had nothing to eat from the homeland. It was not until the late ’70s and early ’80s that the second and third waves came over.” Critical mass gave pho vendors the customers to survive. Today, there are almost 2,000 pho restaurants spread out across the U.S. and Canada, according to PhoFever.com. It lists 62 spots in Maryland, ranking the state ninth for the country as a whole.

In the cramped kitchen at Dooby’s, a Korean-inspired coffeehouse and restaurant on North Charles Street, chef Tim Dyson grabs a fistful of ramen noodles from a package and drops them into one of four small strainers, which he then lowers into an industrial-sized pot of boiling water. “I feel like the next movement in food is very much toward the everyday diner,” he says while waiting for the noodles to cook. “Ramen fulfills that. It’s a little bit of starch, a little bit of protein—that’s the comfort food that people want.”

Dyson doesn’t try to hide the fact that he doesn’t make his own noodles. It’s no secret that almost all ramen shops get theirs from the same supplier: Sun Noodle. The company uses 11 different types of flour, depending on the customer’s requirement for texture or taste, and makes 90,000 ramen portions a day at its factories in Hawaii, California, and New Jersey.

Dooby’s gets its fresh noodles in twice a week. That’s the easy part. Making tonkotsu, or pork-bone-based broth, is by far the more time-consuming portion of the process. Dyson uses seaweed, mushroom caps, and pigs’ feet for the gelatin and the base of the stock. He adds roasted chicken bones and pork necks, and then finishes it with bacon scraps. It takes about two days to prepare before simmering throughout dinner service. Tare, or seasoning (miso, soy, and salt are the most popular), is placed on the bottom of the bowl, which is filled with broth, then topped with the noodles, protein, and garnishes such as a soft-boiled egg. For a dish that emerges from the kitchen so quickly after it’s ordered, it’s hardly a fast food to prepare.

“We’ve found a ramen that we think is a good fit for who the audience is today,” Dooby’s Han says. “We don’t go super heavy on the pigs’ feet when we make our broth, because we don’t want to do overkill on the sticky-lip feel, which you’d find in a very classic, heavy pork tonkotsu ramen where you get a sticky, gelatinous feel. Ramen is very much a self-interpreted dish. Ramen shops in Austin, TX, top it with Texas-style brisket. Our take is more Korean, and not classically Japanese. We’ll feature our house-made kimchi as a garnish, which brightens the bite.”

At Ejji, chef and co-owner Ten Vong serves miso corn and Malaysian curry broth, in addition to the traditional tonkotsu. The Baltimore-born chef returned to Baltimore from New York, where he estimates there are 60 ramen shops. (For comparison, United Kingdom newspaper The Independent recently reported that there are 4,000 in Tokyo, and 80,000 throughout Japan.) “We are doing a more nontraditional take,” says Vong, who also gets his noodles from Sun. “A lot of the younger people are driving it. I see a demand for it everywhere, especially in markets where they don’t have any. Baltimore [has] just started getting dedicated ramen shops.”

While the dish has been on the crowded menus of Asian grab-bag restaurants like Nina’s Espresso Bar on Calvert Street and Shiso Tavern in Canton, Baltimore didn’t have its first dedicated ramen shop until TenTen opened in 2014. The Mt. Vernon shop offers a wide variety of traditional ramen, as well as specialty bowls like curry and chop chashu men. Ejji soon followed, and now the dish is popping up in more and more restaurant kitchens around town—with some creative interpretations.

“I love ramen, but I make pasta and we have a wine bar,” says Cyrus Keefer, executive chef at 13.5% Wine & Food in Hampden. His solution? An Italian ramen hybrid. “I make my ramen broth with our salumi. I take all the ends and utilize the umami from the salumi making. I use black garlic for depth. I take the capellini and poach it in baking soda water to give it the same tone as you would get from the ramen noodles, and then we finish it with pickled mushrooms and bacon. The result tastes like ramen.”

When Jason Chang opened his family’s sixth Katana sushi restaurant in Canton earlier this year, he made one addition to the menu: ramen. The only problem was that neither he nor his parents knew how to make it. So they got a lesson and some pre-made frozen broth from their food distributor, JFC International. “Now we buy pork bones and make our own fresh broth that we simmer in the back for three or four days,” he says. “I got much better feedback from the customers. I felt the business would do good in a city environment with young people, because people drink and they eat noodles.”

That’s one of the reasons Saigon Today opened just a few blocks east in Canton. The fact that the neighborhood, better known for cheap pizza, now boasts a ramen shop and a pho joint says something about the growing popularity of noodles. In Mt. Vernon, next-door neighbors each offer pho. While it’s one of many items on the menu at Minato, it’s a star at Indochine, whose co-owner, Amy Nguyen, uses pork bone’s beef marrow, ginger, star anise and cinnamon sticks in her stock. Her rice noodles are supplied by a California vendor.

Nguyen was 8 years old when she arrived here from Vietnam in 1987, a year younger than aforementioned pho pro Luan Nguyen (no relation) was when he survived a harrowing three-day boat trip from Vietnam to Thailand before ultimately landing in Rochester, NY. He became a high-school English teacher and taught in Baltimore’s Cherry Hill neighborhood before returning to Vietnam to teach for another seven years. He and his wife, Tuyen, moved back to Baltimore in order for their sons to have an American education. They opened Mekong Delta so they could work together, and it quickly became Baltimore’s go-to spot for pho, earning a reputation for quality and authenticity.

“I was very impressed with the first taste of the broth,” food blogger Victoria Tran wrote in her 2013 review of Mekong’s pho. A flight attendant from San Francisco, Tran has made it her mission to eat a bowl of pho in all 50 states. She’s made it to 27 so far, and recorded her findings on her blog, PhoAcrossAmerica.com. “It was a tad salty, but very good. I cut the saltiness with lime and discovered that the broth, a little darker than what I’m used to, contained a masterful blend of spices. It had a slight sweetness and a rich array of flavors. . . . Overall, it was really a great bowl of pho. It was so flavorful and warm, like a Vietnamese hug.”

That’s not a coincidence. A small, soft-spoken woman, Tuyen Vo learned to cook from her grandmother in Vietnam. She listens as her husband translates.

“What’s the key to making great pho?” he relays. She waits for a moment, and then answers in Vietnamese, as a smile spreads across her face.

“Just a feeling,” she replies.

Noodle Know-How

There’s no one way to eat ramen and pho. While some noodle lovers might dig in without a plan, others take more of a step-by-step approach. Here are the expert’s suggestions on how to slurp:

1. Much as you’d taste an entrée before adding salt or pepper, sample the broth before adding hot sauce, hoisin, or anything else for that matter. Says Phil Han of Dooby’s: “That will tell you if the quality is there. Can you find the true spirit of the broth?”

2. Grab the ladle with your left hand, the chopsticks with your right. Use the chopsticks to taste the noodles first, then the ladle to sip the broth. (Bring your mouth down to the chopsticks over the bowl, not your chopsticks up to your mouth. In other words, sticking your face in the bowl is considered kosher.)

3. After trying the noodles and broth, mix everything up. Now, feel free to dive into the protein and garnishes.

4. Remember, slurping is perfectly fine! (In fact, slurping—and burping—is considered a compliment to the chef.)

5. While no one knows why, it’s customary to leave a little broth at the bottom of the bowl, which is the norm in Asia (though very much optional here).