News & Community

Joe Knows

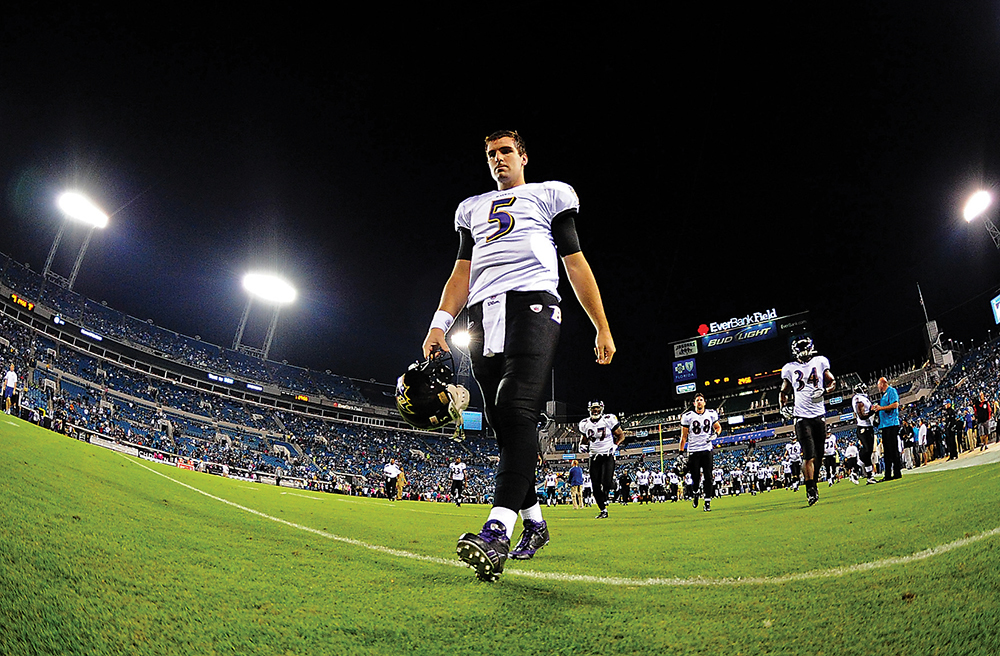

The Ravens quarterback thrives off a cool confidence, thick skin, and love for his growing family.

The drive of Joe Flacco’s life didn’t begin in hostile Heinz Field or even in a stadium. It

originated in the predawn hours of June 13 at his home in Owings Mills

following a phone call from his wife, Dana, and concluded 135 minutes

later in a hospital room in Voorhees, NJ.

“At a quarter to five in

the morning she called me and was like, ‘I haven’t gotten any sleep all

night, I’ve been debating calling you for two hours. I think it’s

time,’” he says six weeks later, at ease on a couch in an office at the

Ravens’ Under Armour Performance Center. “So I was like, ‘Call your mom

up, call your doctor, see what they say.’ They told her, ‘Take your time

but come in.’ She got in around 6:30 and they told her, ‘It’s time,

you’re staying.’”

Flacco was excused from practice, jumped into

his Ford F-150 and raced up I-95. “I left here at like 6:45 in the

morning and got up there around 9.”

The NFL’s most-successful-yet-still-curiously-maligned quarterback was determined to witness the birth of his first child.

“Everybody

was [asking] me, ‘Are you gonna look? You don’t want to do that,’” he

says. “I was like, ‘I’m definitely looking.’ I was right there on the

side of the bed, I watched the whole entire thing, from the time when

you could barely see his head to the time he was out. It was pretty cool

to see him come out.”

A slight smile creeps onto Flacco’s face as

he recounts the day, his most momentous one in a year filled with them.

Throughout a season that included a scintillating comeback in

Pittsburgh and a heartbreaking playoff loss in New England, criticism

from within the organization and a media-driven “controversy” fueled by

his candor—not to mention, contract negotiations that seemingly devolved

from complicated to contentious—Flacco’s public demeanor remained

unchanged.

It’s all white noise to the impossibly even-keeled QB,

who thrives on the steadiness that so maddens fans who mistake it for

stoicism.

“We taught him never let anybody see you sweat,” says

his father, Steve, for whom Joe and his high-school sweetheart Dana

named their son Stephen. It’s a lesson Flacco, 27, has leaned on

throughout his unlikely career, one that’s won him an unprecedented

number of football games but no popularity contests.

“My dad’s my

best friend,” he says. “The biggest thing he preached was being tough. I

think a tough guy doesn’t really show many emotions. Not to say that I

don’t have emotion, because that’s not true. But when things are going

bad, as a leader, you can’t act like anything is wrong. You go out there

and take each snap like it’s the same, no matter what the score is, no

matter what happened on the last play. It’s just the way I was brought

up, it’s the way my parents are. You definitely end up more like them

than you admit.”

“Until I got here, they hadn’t won a playoff game since the Super Bowl year. Every year we’ve won a playoff game. It’s not what we want to do overall, but we’ve had very good seasons.”

If that’s true—and most of us eventually concede

that it is—then, throughout his life, little Stephen Flacco, like his

daddy, will cherish two things above all others: family and football.

Of

the NFL’s 32 starting quarterbacks, Joe Flacco may be the only one

who’s been ribbed his entire life for having a big head—literally.

“His head was always humungous for his body,” says his brother, Mike, a baseball player in the Orioles minor-league system.

“They

call him the Kingdome, the Superdome,” his father says. “When he was a

sophomore in high school he was six-four, 165 pounds with a size 7 ½

head.”

The oldest of five boys and a girl, Joe seldom got into

trouble throughout his childhood in Audubon, NJ, a suburb of

Philadelphia.

“He was very responsible,” his mother, Karen, says. “He was known as Father Joe.”

Baseball

was Flacco’s sport of choice until seventh grade when Steve, a former

running back at the University of Pennsylvania, allowed him to try

football.

“Because I started so late, by the time I got there,

they already had kids who had been playing quarterback, so I played

running back, tight end, receiver,” Flacco says. “I always had a knack

for throwing the ball. I can’t remember a time when we didn’t go out and

mess around and play football as much as we could. I always had a

pretty good arm, so I knew I wanted to play quarterback.”

In high

school, Flacco shot up to over six feet, the first in the family to

eclipse the mark. His father is 5-feet-11-inches, his mother 5-feet-6.

Despite putting up gaudy numbers—he once threw for more than 450 yards

and three touchdowns and ran for two more in a 67-35 loss—Flacco

received only a smattering of scholarship offers. He accepted one to the

University of Pittsburgh.

After redshirting his freshman year and

serving as a backup his sophomore season, Flacco transferred to the

University of Delaware, much to Pitt’s chagrin, where he figured he’d

have a better chance to play, even if it wasn’t in the spotlight of

Division I-A. “Joe is a tremendously gifted athlete,” Delaware coach

K.C. Keeler says. “He’s just got a world of talent, and you could see

that very quickly when he got here.”

Because Pitt was upset that

Flacco transferred, the school chose not to release him, forcing him to

sit out a season. When he got a chance on the field, Flacco led Delaware

to the Division I-AA national title game his senior year, smashing

school records in the process. NFL scouts started showing up in droves.

“I

remember Joe calling me during the whole draft process, and he was a

little upset because [Ravens general manager] Ozzie Newsome had called

two or three times and had asked why he wasn’t a captain,” Keeler says.

“It was one of those strange years where we had a consensus All-American

tailback, who was a four-year starter for us, and we had an

All-American offensive lineman. Those two guys were voted the offensive

captains.

“But the team was Joe’s. He said, ‘Can someone tell

those guys with the Ravens that this was my team?’ The best thing I said

was this team took on Joe’s personality; it never ever panicked. It

played with a steady belief in itself. It never got too high or too

low.”

Apparently, Newsome was convinced.

Baltimore took Flacco

in the first round of the 2008 draft, making him only the second

Division I-AA quarterback in history drafted that high. When the season

started, Flacco was under center.

“Obviously I didn’t know as

much as I know now, but I think the biggest thing for me as a young kid

was to calm my mind down and say, ‘Hey, it’s football, go out and

play,’” he says. “When I was a rookie, I didn’t want to come in here and

step on people’s toes and act like I was some big deal. I felt like I

had to prove myself.”

Flacco and a fellow rookie, head coach John

Harbaugh, led the Ravens to the AFC Championship game, and both were

praised for exhibiting poise beyond their years. Yet, as the victories

kept coming—Flacco’s 44 regular season wins are the most by a starting

quarterback in his first four years in the NFL—his reputation morphed

from a stable leader to a “game manager” incapable of using his arm to

lead the defensively-strong and run-oriented Ravens to victory.

“I don’t think there’s any other quarterback besides Aaron Rodgers that can throw the ball the way that he can.”

“Sometimes

I think people perceive [the team] a certain way just because that’s

what we’ve been over the last 10 years,” he says. “Well, you know what?

Until I got here, until John Harbaugh got here, they hadn’t won a

playoff game since the Super Bowl year. Every year we’ve been here we’ve

won a playoff game. It’s not what we want to do overall, but we’ve had

very good seasons.”

None better than last, when Baltimore swept

the Steelers, won the AFC North division and came within one late

dropped pass of making it to the Super Bowl. Yet Flacco’s play still was

criticized. After a playoff win against Houston in which Flacco put up

pedestrian numbers, Ravens safety Ed Reed said it didn’t appear his

quarterback “had a hold on the offense.”

Flacco nonchalantly brushed aside the comment and proceeded to outplay Patriots legend Tom Brady the next week.

In April, Flacco appeared on local sports radio station WNST and was asked if he considered himself a top-five quarterback.

“Without

a doubt,” he responded. “What do you expect me to say? I assume

everybody thinks they’re a top-five quarterback. I mean, I think I’m the

best. I don’t think I’m top five, I think I’m the best. I don’t think

I’d be very successful at my job if I didn’t feel that way. I mean, come

on.”

Hardly a shocking answer, yet one that created a firestorm.

Anti-Flaccoites rolled their eyes, noting that his 2011 QB rating was

14th (out of 34 players). Of the more than 95,000 votes in a

SportsNation online poll, 61 percent indicated Flacco was not an “elite”

quarterback. Whatever that means.

“Joe doesn’t play games, he’s

going to tell you honestly how he feels,” Delaware coach Keeler says.

“It’s not like, ‘Okay, what would sound best in a sound bite?’ It’s not

that he’s not savvy—he is as smart as the day is long—but he’s not going

to compromise his belief system. [His attitude is] I know you’re going

to take the sound bite and use it however you want, but I’m not going to

change who I am. Like it or leave it, this is who I am.”

Perhaps

Flacco’s quiet disposition contributes to the way he is perceived. Fans

screaming at their TVs like to see similar outward emotion from their

heroes.

“Unless you are in the locker room or you know me, it’s

tough to get a read from me because I’m not a very outgoing person,” he

says. “I’m not really vocal in the way a rah-rah kind of guy is. I don’t

think [leadership] is when things are going bad let’s go yell at

somebody and get them fired up. I think we’re a bunch of professionals.

If we’re not fired up, something’s wrong. A pep talk ain’t gonna do

anything for anybody. Pregame speeches on Saturday night, I don’t think

they do anything, so I’m not gonna do them. When it all comes down to

it, we all have to have a little bit of self-motivation, and when Sunday

comes, we have to be able to turn the switch on. If we can’t do that,

we shouldn’t be professional football players.”

Matt Birk,

Flacco’s center for three years, sees Joe’s stoicism as an advantage.

“Joe’s always been Joe,” he says. “Joe might be a little bit quieter,

but, at the same time, when Joe does speak up, he’s doing it because he

has something to say. It’s kind of like the old E.F. Hutton ad: When Joe

talks, people listen.”

Flacco’s record speaks for itself. Since 2008, he has won more games than any quarterback in the league.

Phil

Simms knows a little something about winning. He earned two Super Bowl

rings quarterbacking the New York Giants, and is CBS Sports’ lead NFL

color commentator.

“If you put Joe Flacco in a quarterback-driven

offense with a franchise and a head coach and an owner . . . who’s

behind him, he would throw up numbers that are [impressive] just like

all these other guys,” he told SiriusXM NFL Radio in July. “But he’s not

on that type of team, he’s not [with] that type of head coach. What he

does with that organization for that football team, I think, is as good

as anybody else in the league.”

Rob Agnone played with Flacco at

both Pitt and Delaware. He spent a season with the Patriots, which makes

his analysis of Flacco that much more striking.

“He has more

natural God-given talent than any of the quarterbacks I’ve played with.

It’s not even close,” he says. “Tom Brady is by far the best quarterback

in the NFL, there’s no doubt about it, but just going off God-given

talent, arm strength, accuracy, I feel Joe has more ability than him. He

hasn’t proven it with [big] wins, and I think Joe would tell you the

same thing. He’s got to win the Super Bowl to be in that level, but he

has the talent to do it.”

Ravens wide receiver Anquan Boldin, who played with future Hall of Fame quarterback Kurt Warner in Arizona, agrees.

“I

don’t think there’s any other quarterback besides Aaron Rodgers that

can throw the ball the way that he can,” he says. “He can make any throw

on the football field, from hash to sidelines, deep balls, you name it.

I definitely think he’s a top five quarterback. But he don’t care about

all that.”

Flacco is uninterested in the debate. His confidence

is iron-clad, his skin thick. He claims not to watch ESPN, instead

preferring to keep up with the Kardashians or other reality shows with

Dana.

“I don’t care how much respect I’m getting in the media, as

long as I feel like the people in this building respect me, then I’m

cool,” he says. “If it ever came to a point where I didn’t feel that

way, that’s when I’d feel a little bit hurt.”

“We all, at some point, started to play this game because it was fun. We lose track of that.”

Maybe 2012 will be

Flacco’s breakout year. The Ravens are using a more wide-open offense;

his first pass of the season was a beautiful 52-yard bomb to Torrey

Smith. Could that have been a harbinger of things to come, or is Flacco

destined to be remembered as Trent Dilfer is, a quarterback the Ravens

won in spite of?

“If that’s what people say, that’s what people

will say, it doesn’t mean it’s the truth,” he says defiantly yet not

angrily. “I hope we throw for 5,000 yards and win the Super Bowl. I

don’t want to be throwing for 150 yards a game and winning. I’ll take

it, but I feel that I give us the best chance of winning, doing what I

do best.”

Such is Flacco’s complicated relationship with Baltimore

that when he cancelled his annual appearance at the Special Olympics’

Polar Bear Plunge just a few days after the New England loss to spend

time with his pregnant wife, some actually ripped him apart.

Adam

Hays was not among them. A 28-year-old Special Olympian from Frederick,

Hays has met Flacco several times at events, including a casino-night

fundraiser a few weeks before the Ravens hosted him at training camp

this summer.

“When Joe came by what was really exciting for me was

to hear him say, ‘Nice to see you again.’” says Hays, who wears a

Flacco No. 5 jersey during Ravens games. “He’s very cool, and it seems

like he’s very relaxed. He seems like he’s very kind to everyone that he

comes in contact with. When I look around at my fellow athletes seeing

that Joe and the Ravens take their time out to help show us the skills

in football and just to be with us, it shows that they think of people

with intellectual disabilities as athletes out on the field. It really

means a lot that they see past those barriers.”

Flacco seems

unaware that his mere presence has such an impact on people’s lives. He

politely deflects a question about his work with the Special Olympics,

saying it’s something he enjoys immensely.

“It’s cool to see the

athletes out there having fun,” he says. “We all, at some point, started

to play this game because it was fun. We lose track of that.”

Throughout

his career, he has never lost track of who he is. He’s a father, a

husband, a son, a brother. He’s extremely confident in his athletic

abilities. He’s a winner.

What he’s not is an actor. His work for Pizza Hut makes Ray Rice’s commercial performances look downright De Niro-esque.

“I

feel completely awkward doing that stuff, but, sometimes, it’s too good

to turn down,” he says. “I turn off [my ads] as soon as I see them. If

I’m in the car and I hear my voice on the radio, I turn the station.”

Flacco

recently bought a house in New Jersey a mile from both his parents’ and

Dana’s. His folks attend every home game, and, before Stephen arrived,

the family used to hit a diner afterwards, win or lose. He’s so

comfortable in his own skin that he describes himself as a “pretty

boring person,” who likes to “play a little golf and hang out with the

family.” Not exactly Tom-and-Gisele tabloid fodder.

“He’s always

here after hours in the building, up by himself watching film, making

sure he knows the defensive looks, making sure he’s got a leg up on the

competition,” says tight end and close friend Dennis Pitta. “Every time I

get here, his car’s in the parking lot, and every time I leave, it’s

still here.”

When he climbs back into the driver’s seat after

another long day, Flacco heads to an ever-growing household. His younger

brother, Brian, and nephew, David, are living with him, Dana, and

Stephen, and it’s a safe bet that the family will expand soon.

“I

can’t imagine not having a good amount of people in the house,” he says,

his voice thick with a South Jersey drawl. “I’m not saying I need six

kids, but I wouldn’t complain if we get to that point.”

Is he a top-five quarterback? Let others waste their time with meaningless lists. Joe Flacco’s got work to do, games to win.

And a family to get home to.