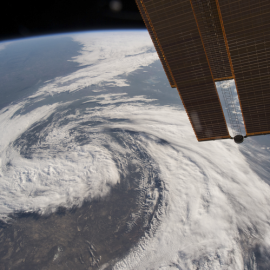

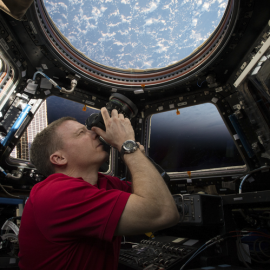

In many ways, Terry Virts is just your average native Marylander. He loves the Orioles and fondly recalls growing up in Columbia during the 1970s and ’80s. How is he not like the average Marylander? Well, as a retired astronaut and one-time commander of the International Space Station, he has spent 213 days in space, which he documented extensively in thousands upon thousands of hi-def videos and still photos. Since retiring from NASA in August 2016, he has spent his time organizing his images and career recollections into a book, the newly released View From Above: An Astronaut Photographs the World. While in town on his book tour last week, he stopped by Baltimore’s offices (where he geeked out about our Orioles-themed décor) and answered our questions about growing up in Columbia, working with the Russians, and thinking he might die in space.

*This transcript has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The book just came out last week and is the result of your 16-year career with NASA, including your stint on the International Space Station, during which you took the most photos anyone has ever taken from space. That’s what they told me, yeah. When I landed, they were like, ‘Ugh. Finally, you’re back on Earth.’ Because they told me I took 319,000-plus pictures.

Were they ever like, ‘Maybe hold off taking pictures for a day or two?’ Oh, totally. And it wasn’t just fun pictures. Like sometimes, if you’re doing an experiment, they want three different views. If you’re filming experiments, that payload stuff would kill all the downlink so there’s no time to get your fun stuff down. We had RED, this Hollywood-quality camera. Jim Cameron told me he used it to film Avatar. The RED camera was the worst. My last week I was like, ‘You know what, I took enough stills.’ So I got the RED out, and they had always warned us to be real judicious with it because it uses so many gigabytes. But I just filmed away, and they were like, ‘Oh my God!’ But you know what, a week later they had it all down, and they made the most popular UHD highlight reel. It was a couple years ago when UHD was new. It’s amazing. And they’ll have that forever. Yeah, it was like, ‘Sorry. You’ve got to download it.’

So tell us something about space that the average person doesn’t know. So it’s nothing like Star Wars. The Wookiees are not that loud in real space. The Storm Troopers are actually nice guys. [Laughs]

Well, tell us about floating. In space, you move with your hands and you carry things with your feet.

Why? Because you have to grab onto handrails to push yourself around. The way we’re designed: Hands are fine motion and feet are [mimes pounding his feet]. You can do that [mimes jumping], but you’re going to shoot up to the ceiling.

What are the annoying parts about being in space? Well, floating is super annoying. Like, anybody can move over there and get to the door, but to end up at the door [facing it with your hand near the handle], you have to push and rotate at the correct number of degrees per second and your brain has to figure out that it’s going to take five seconds to get there and I need to rotate 10 degrees.

How long does that learning curve take? The first couple of days, it is pretty steep. After a week, I was still not there. After two weeks, I was good but I wasn’t [at my peak]. It probably took me a month before I was good, and I got really good.

What about sleeping in space? Yeah, you get sunrise and sunset every hour and a half, unless you’re in high beta [orbit]. I went through a week with no sunsets.

It’s like living in Scandinavia in the summer or something? Right or Antarctica in the winter. It’s just constant sunlight. So you close the windows and you don’t know what the sun is doing and you set your alarm to GMT [Greenwich Mean Time].

Why GMT? Because it’s the International Space Station and the bus and the subway system [in Russia] does not run in the middle of the night. So we had to pick a time that was close to their normal work hours for their mission control people. Going GMT is close, it’s a couple hours difference. We didn’t just cave and use Moscow time. So it kind of saves face for us. [We can say] ‘Okay, GMT, that’s official.’ But the real reason is the Moscow subway schedule—so I’ve been told. I was still in the Air Force when the [ISS was launched].

Speaking of the Russians, you were up on the ISS with how many others? Five others. There were three Russians, two Americans, and an Italian.

This was in 2015, which, even then, was a tense time in U.S.-Russian relations. How did that affect your working relationships? It was great. It was the highlight of my mission having my Russian crewmates there. It was a lot of fun to hang out with them. We all knew that these things were happening on Earth and we would just consciously, actively say, ‘We’re going to ignore the politics and focus on staying alive.’ Because on the other side of the window is vacuum and death. In a universe of a lot of bad stuff happening, the space station was a good example of how people can work together.

Can you give an example of something political that threatened to divide you? Well, [the U.S.] put sanctions on Russia. And when that happened, the ruble got devalued in half. So my cosmonaut friends were calling home asking their wives, ‘Hey, what’s going on?’ And I’m the guy that did it, and I’m commander, so that could have been very divisive. So I made a very active decision to spend time with them, have dinner with them, to talk. And actually, the cosmonauts are paid in dollars—that’s just the way their contract is—so in the long run, their salaries doubled.

And then [the U.S.] had an orbital rocket that blew up here in Virginia, a Russian Progress rocket blew up, and a Space X rocket blew up. Three rockets in eight months. When the Progress blew up, it was the Soyuz [Russian spacecraft] rocket after [the one that delivered me to the ISS], so they wanted to do an investigation before they launched the next crew to replace us. So we didn’t know how long we were going to be stuck in space. And we were very flexible. Every day I would say, ‘Okay, guys, tell us your rumors,’ because I didn’t want rumors. I was like, ‘Let’s get ’em out. What is everybody hearing?’ And the Russians had the best because it was their rocket. I would talk to the station program manager [at NASA] and he was great. He was just like, ‘Here’s what we know. The reality is, it’s their rocket and they’re going to decide.’ I was like, ‘Okay, I can deal with that.’ There have been other examples when crews got delayed—or they didn’t even get delayed; they had threats of delays—and they were like, ‘Arggghh!’ But we were very positive. And our international partners get paid by the day. When they get extended, they get paid even more. The folks were not that upset about having to stay longer.

You were born in Baltimore, grew up in Columbia, graduated from Oakland Mills High School. What are your memories of growing up in Columbia? I lived in Lanham and Gambrills first. I didn’t move to Columbia until fourth grade. My fourth grade teacher just found me on Facebook. He remembered stuff. He was like, ‘There was this trip to D.C. and you bought a prism, and you spent 15 minutes explaining how a prism works.’ I remember that but it’s crazy that he remembers that.

So obviously you had an aptitude for science. Yeah, math and science were my strong suits.

What was your experience going through Columbia’s public schools? It was amazing. The public school system then, that I went through, was rated one of the, I think, top 10 in the country. First of all, it was a multi-racial place. It was kind of weird because I didn’t really think about when I was growing up because I had friends of all [backgrounds]—a Korean guy, an Indian guy. We had everything, and it just wasn’t a big deal. And academically, it was amazing. I got to take Calc 3 in high school and had French every year, seventh through twelfth grade. I became a French minor. I became an astronaut because of my French experience. Madame Micka, I talk about her in my book. She was my French teacher in high school.

What do you mean you became an astronaut because of your French experience? There are 100 test pilots who are great, but I was the guy who had done an exchange at the French air force academy, and I had international foreign language [experience]. For something like being an astronaut that’s so competitive, you want to have something that makes you stand out, and that made me stand out. No one ever tells you why they picked you, but I just know in my heart that it wasn’t only math and science, it was also the language side of things that got me in.

You really did want to be a pilot from a young age. There’s a cute picture of you in the book standing on the wing of a plane. Where do you think this love of flying came from? The first book I ever read was about Apollo. It was one of those picture books for kids and I was in Lanham, and I can remember it. It just stuck. My mom was a secretary at Goddard [Flight Center in Greenbelt] and my dad and my stepdad both worked at Goddard. But they weren’t pilots. It was satellites, not human space flight.

But you were around the culture. Yeah, they would bring home pictures. I remember when Viking landed on Mars I got pictures from Mars. They would get, probably, posters from books they could bring home. They would just bring stuff like that home and my room was just covered with airplanes and stuff. And every summer I’d get Astronomy magazine and, the day it showed up, I would sit there and read the whole thing.

Do you think a human is going to go to Mars? I’m sure, eventually. I hope sooner rather than later, and I hope America leads it. If we don’t, other countries will. The thing about humanity is that nothing is static. Just ask the Portuguese, ask the Brits, or ask the Chinese. They decided to build a wall, and for 1,000 years they just wallowed in themselves and they didn’t grow. The whole world did this [mimes expanding] and China was behind the wall. So America had the 20th century, right? That was our century. But that doesn’t mean the 21st century is going to be our century unless we decide to make it so.

What is the most dangerous situation you’ve ever encountered in spaceflight? There’s a whole chapter in the book about it called “Emergencies in Space.” There was an ammonia leak. We’re sitting there, minding our own business, and the alarm goes off, and we pop our heads out. Samantha, my Italian crewmate, we’re looking at the panel. I see ‘ATM.’ There are three kinds of emergencies: There’s fire. There’s an air leak. And there’s toxic atmosphere, which is ammonia inside the atmosphere. Ammonia is the coolant. So cars have radiator fluid, the station uses ammonia. That’s how it stays cool—on the American side. The Russian side uses sugar water. It’s not as efficient. It’s not as good a coolant, like ammonia, but it’s sugar water. Ammonia kills you dead.

So I go, ‘ATM?’ It was such a big deal that I just couldn’t process it. So we put on oxygen masks, run down to the Russian segment, and close the hatch because the Russian segment is safe. And then you’re supposed to take all of your clothes off because if there’s ammonia in your clothes, its poisonous, and then you go through another hatch. But we didn’t take our clothes off. No one smelled anything. We were like, ‘We’re probably fine.’ And the ground was kind of mad at us about that. Thirty minutes [later], the ground goes, ‘Hey, just kidding, it was a false alarm.’ So we’re just like, ‘Ugh.’ It just kills the day’s schedule. So we get back and we’re putting things away because we had just dropped everything and the CAPCOM [the Capsule Communicator] calls up and says, ‘Execute ammonia response now. This is a real thing. This isn’t a drill.’ It was this super intense voice. We were like, ‘Crap!’ We put the masks on, we go down, we close the hatch, we don’t take our clothes off. We do the whole thing. We get a sampler out. Okay, the air is good. Twenty or thirty minutes later we take our masks off and we’re like, ‘huh.’

What I knew had happened was the computer [activated] the alarm automatically. I knew there would be a crowd of engineers looking at every little bit of data. What I assumed had happened was, after the first alarm, they went, ‘Nah, that’s not really a leak. Tell them it’s not.’ And then they [continued] to watch the data and it [looked] like it was still leaking and they said, ‘Yeah, that’s a leak. It’s a small one, but it’s a real leak.’ And then they called us back. Since I’ve worked in mission control for years, I knew what was going on; they didn’t tell us this. And then we sat around for hours on the Russian side and the Russian deputy prime minister called up in the middle of sanctions and all these bad things and says, ‘Hey Americans, you can stay as long as you want. We’re going to work together.’ This was the same guy that had said we could take a trampoline to the space station after the U.S. had put sanctions on Russia. The same guy who was having a Twitter battle with, I guess, Obama at the time called up and said, ‘Hey we’re going to work together and get through this.’ So it was a great, great, great example international cooperation in space when things were really bad down here.

So we spent the day like, ‘So, there’s a small leak on the station.’ What’s going to happen if it continues to leak is the station pops. It just gets over-pressurized and the metal explodes—unless they vent it. They could vent it and then there’s no air and ammonia stuck to the walls. So we’re like, the station’s dead, and we’re going to stay on the Russian segment for a few weeks—with the one pair of underwear because all my clothes are over there—and then go back to Earth and the station will go into the Pacific. And then I went and took a nap. I was like, ‘I don’t have anything else to do. I’m going to take a nap.’ And then they called up and said, ‘Just kidding, it was a false alarm.’ [Laughs]

But then when we went back to the American segment they said, ‘But just keep your masks on just in case.’ So my crewmate and I, we put our masks on and we had these samplers and we were floating around and it was like this surreal alien movie. There were things floating around—we just abandoned stuff and left—so it was like being the first person on this ghost ship in space. And then everything was fine. That’s a story that no one knows and it’s an amazing story.

So, essentially, you got told it was a false alarm twice? Yes. And there have always been false fire alarms, and there have been a few false air leak alarms, but there’s never been a false ammonia alarm.

Ever? That’s the one and only ammonia alarm. The ammonia alarm is a big deal. That’s the one you don’t want to get. They sent a text to my family at four in the morning. The text is in the book. My wife got it and she gave it to me for the book. In general, space flight sucks for families. It’s just hard. Everyone’s always like, ‘Oh you’re so lucky your dad’s an astronaut!’ My kids are like, [rolls eyes]. We were watching the NBA five or six years ago and my daughter, she was probably like 10 at the time, and we were watching the Heat and they were in the finals and she just looks at me and says, ‘Dad, why can’t you be more like LeBron James?’