News & Community

City of Hope

Fifty years ago, Jim Rouse envisioned a utopian city in Columbia. Has it lived up to his dream?

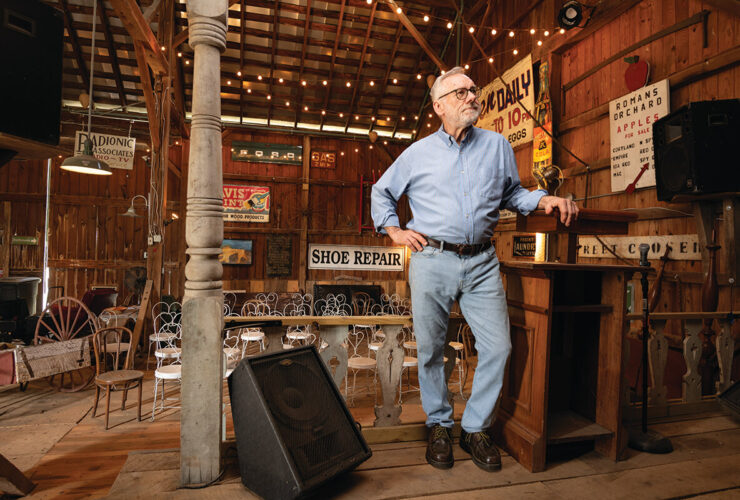

had lofty ambitions. When he began putting his team together to build a city on 13,690 acres of Howard County farmland, the first person he hired was Bill Finley, who had been overseeing the National Capital Planning Commission’s revitalization efforts in Washington. Finley, in turn, hired Mort Hoppenfeld, who also worked for the national planning commission, and then Hoppenfeld recruited Bob Tennenbaum, a young, Yale University-trained urban designer who toiled under him and Finley.

had lofty ambitions. When he began putting his team together to build a city on 13,690 acres of Howard County farmland, the first person he hired was Bill Finley, who had been overseeing the National Capital Planning Commission’s revitalization efforts in Washington. Finley, in turn, hired Mort Hoppenfeld, who also worked for the national planning commission, and then Hoppenfeld recruited Bob Tennenbaum, a young, Yale University-trained urban designer who toiled under him and Finley.

“The Washington project had been one of the first genuine urban renewal efforts and then suddenly Bill and Mort were off to Baltimore [to join the Rouse Company],” Tennenbaum says. “A couple of months later, Mort calls me and wants to meet and he picks me up in Georgetown. The next thing I know, we’re driving up Route 29, which was just a two-lane road. I know nothing about the area; I’m originally from New York and couldn’t even drive.

“When we get to Route 32, Mort slows down and says, ‘Okay, look closely across both sides of the road.’ It’s nice little farms, meadows, cows, and large swaths of woods. I saw some cows with horns and thought they were bulls. Later I found out they were just cows with horns.”

Once the men reached Route 108—roughly where Tennenbaum spotted an old country post office with the designation “Columbia”—Hoppenfeld spills the beans. He tells Tennenbaum about all the property the Rouse Company had begun secretly buying there. “And Mort starts telling me about Rouse’s vision for this new city they’re going to build—racially and economically diverse, with respect for the environment and green space—and he keeps talking until he drops me off at Penn Station so I can grab a train back to D.C.,” Tennenbaum recalls. “By that point, I’m so freaking excited I can’t sit still.

“Mort told me they couldn’t pay me any more than I was making. It didn't matter. I accepted the job on the spot. I was the third person Jim Rouse hired to work on Columbia. That was 1963.”

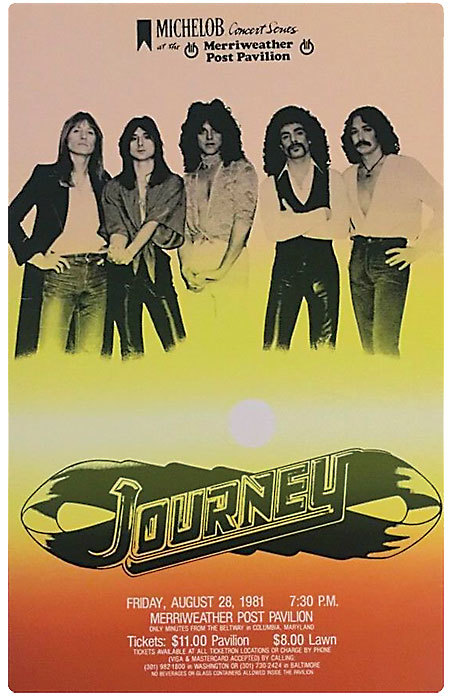

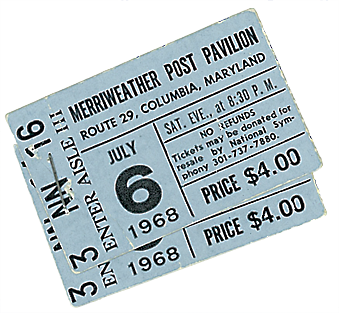

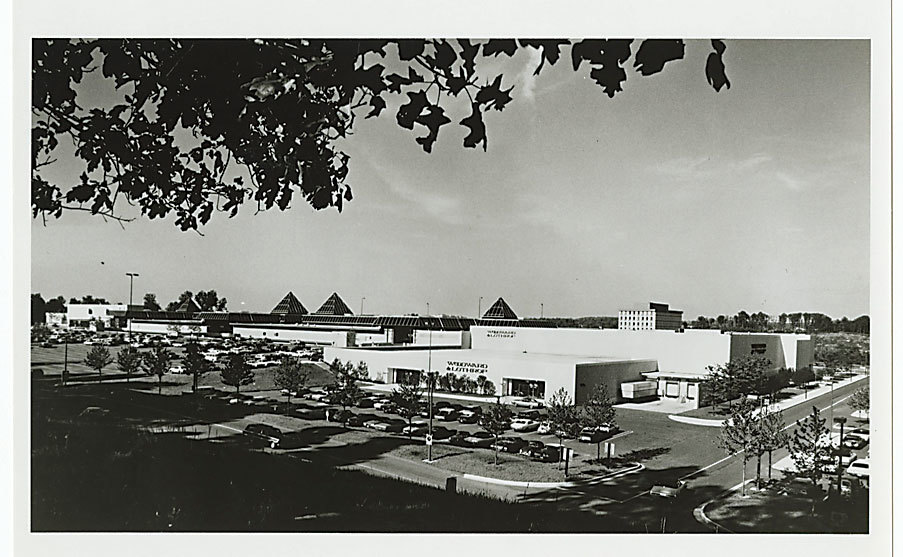

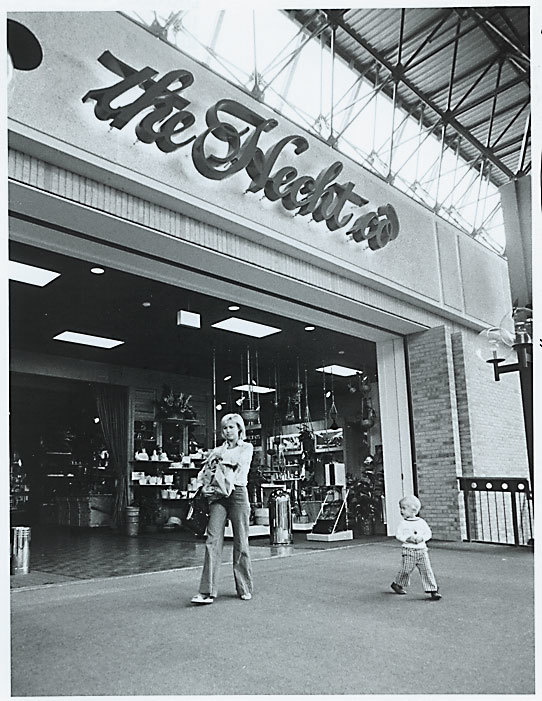

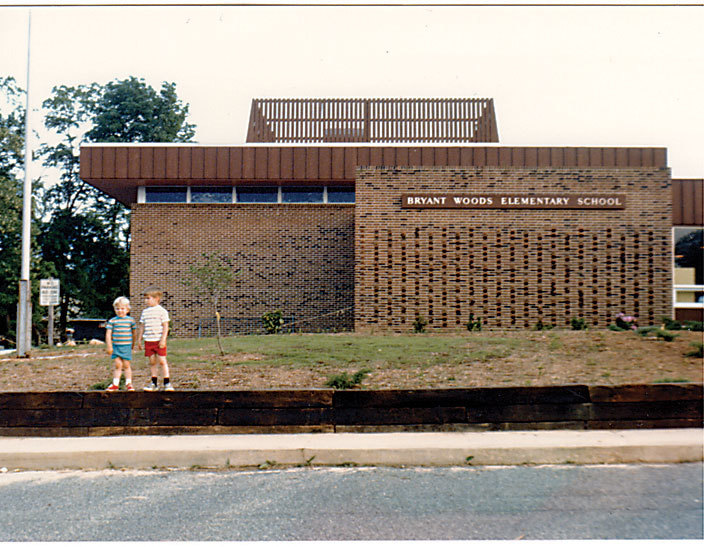

Fifty years after its formal founding on June 21, 1967, Columbia remains one of the most remarkable modern planning achievements in the U.S. Over the past half-century, those nearly empty 14,000 acres have been transformed into a community of 100,000 residents—the second-largest city in Maryland. It is situated in the center of a public school system now regarded as one of the finest in the country, while earning acclaim as the “Best Place to Live” in the U.S., according to a Money magazine report last year that looked at more than 800 cities and towns and touted Columbia’s diversity—55 percent white, 25 percent black, 12 percent Asian, and 8 percent Latino—green space, recreational facilities, cultural amenities, and economic opportunity.

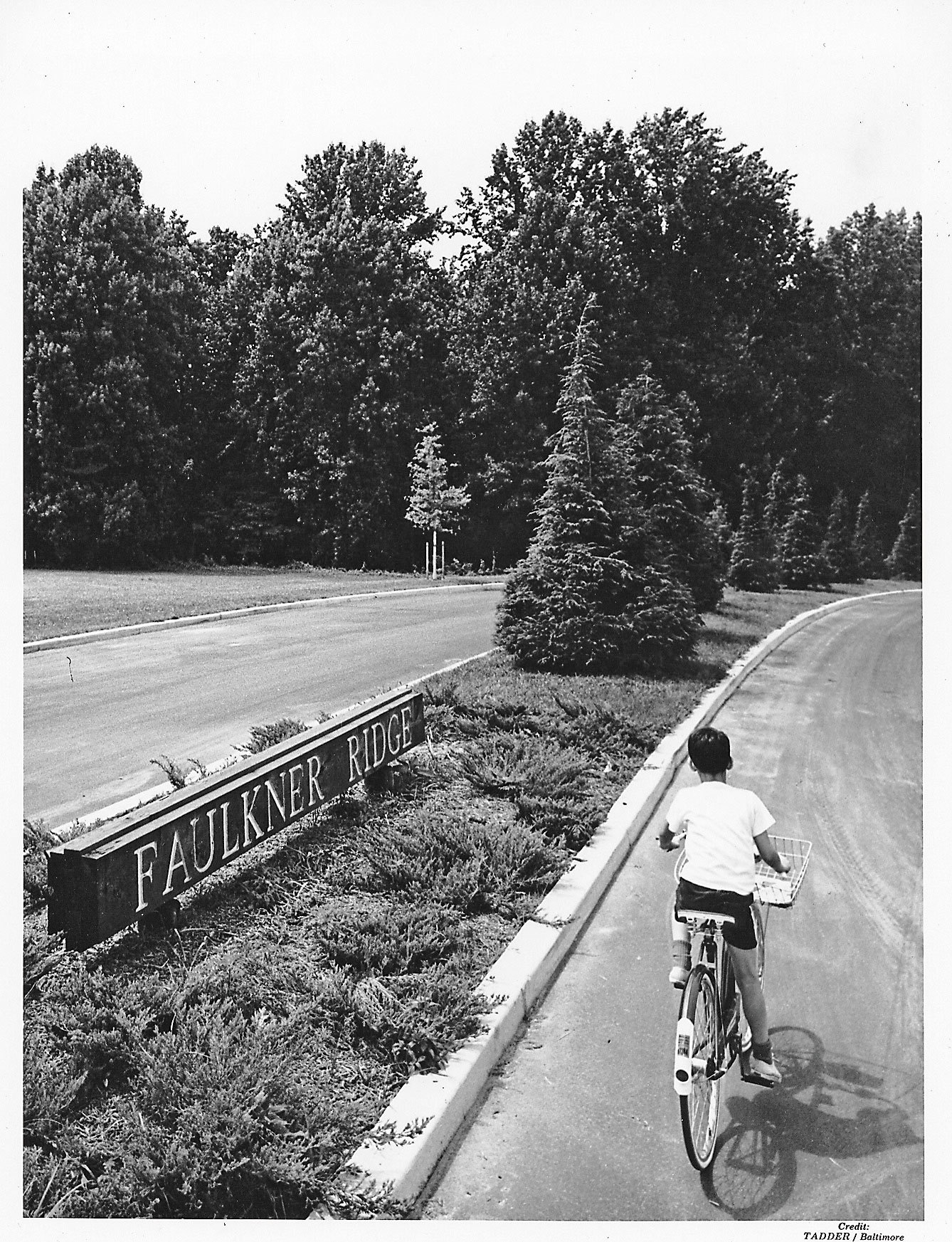

|| A boy rides through Faulkner Ridge. —Morton Tadder / Courtesy of Columbia Archives

“Shangri-La” was the Rouse Company’s aspirational code name for the Howard County project, but Rouse didn’t exactly promise a utopia or perfect city and few would suggest Columbia is either. (Managing economic diversity, one of Rouse’s goals, for example, has been a struggle in several villages of the city, where the median home price today tops $300,000.) But rather he said he was trying to develop an alternative to “the mindlessness, the irrationality, the unnecessity of sprawl and clutter as a way of accommodating the growth of the American city.”

As a developer with Christian gospel ideals, Rouse began expressing frustration as early as the 1950s that after World War II, cities were becoming destructive and impersonal, built with the automobile and commercial interests in mind, but not human flourishing.

He explained his vision as a sort of middle path through the bipolar urban decay/suburban sprawl dynamic that was unfolding in the Baltimore region and elsewhere, much to his dismay. He said he wanted to create “a garden for growing people” who were “creative, tolerant, and caring.” To that end, Rouse organized a famous 14-person workgroup—not only planners and architects, but also leaders in the fields of psychology, sociology, education, health, juvenile delinquency, transportation, religion—to inform the design process. That alone proved a revolutionary concept.

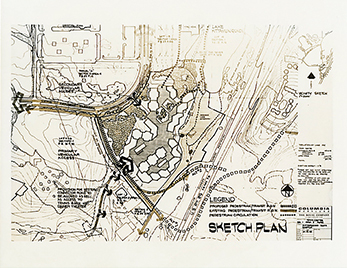

Rather than impose a traditional grid-like street system on top of the downtown topography or around the 10 village centers, Columbia’s built environment was shaped around the natural environment—the streams, brooks, and small valleys, as well as the three lakes made by the Rouse Company. Navigating the inevitably circuitous roads may drive non-Columbians a little crazy, but it makes sense if you live there and appreciate the city’s old trees, connecting walking paths, and parks.

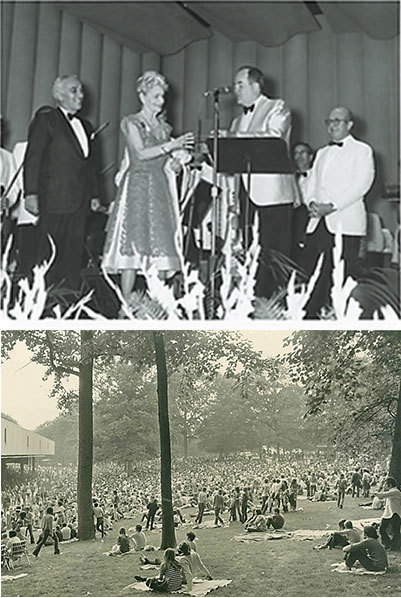

|| Rouse lacing up for a skate on one of columbia’s lakes and leaning back at a meeting; an early sketch of plans. —Courtesy of Columbia Archives and Getty Images

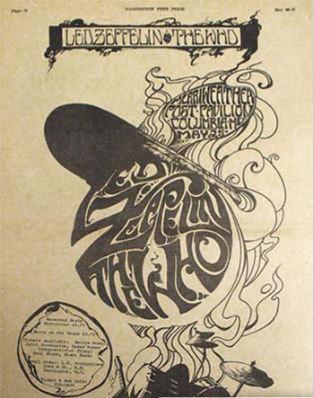

“I remember hiking through the area with a small notebook, no GPS, just USGS maps, and coming across what became Symphony Woods,” Tennenbaum recalls. “I called Mort later and he called Jim, who said, ‘We are going to put a red circle around it.’ Everything was done to preserve the land and that’s why it’s still there.

That the man behind the project was a disheveled, plaid-sports-coat-wearing, middle-aged guy from the Eastern Shore, a politically active liberal Republican in the Eisenhower ’50s, is surprising only in hindsight. It wasn’t to those who knew Rouse or heard him speak publicly. Rouse had undergone a transformative experience in the 1930s as a U.S. naval officer in Hawaii, where he attended school with students of different races and backgrounds and, in one memorable moment, was helped off the track after running to exhaustion by a brown-skinned teammate. He returned to Maryland, according to biographer and friend Joshua Olsen, “with the knowledge that there was nothing natural or morally right about segregation and racial prejudice.”

He said he wanted to create “a garden for growing people” who were “creative, tolerant, and caring.”

“There is a line I use when these accomplishments get highlighted,” says Milton Matthews, president and CEO of the Columbia Association, a nonprofit service provider that also maintains the operation of the community’s green space and amenities. “It didn’t happen by happenstance. Remember not just how different Howard County was in 1966—considered one of the worst counties in Maryland—but how different the country was.”

Today, downtown Columbia is undergoing a major renovation to add density and walkability to the city’s core—a component of Rouse’s initial vision. And several village centers—Long Reach, Oakland Mills, and Hickory Ridge—are in the early stages of needed redevelopment. After a long period where Columbia felt complete, it is now growing again.

“I still remember learning about Columbia as part of a case study 40 years ago in my city and regional planning master’s program at Ohio State,” Matthews says. “It was a radical idea then. It still is.”