*If you have experienced or are experiencing sexual abuse, help is available through the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN). Please call 800-656-HOPE (4673) to be connected with a trained staff member from a sexual assault service provider in your area.

**Be aware, this post includes spoilers for the Netflix docu-series The Keepers.

**This post has been updated with new information regarding the Archdiocese of Baltimore’s participation in the documentary, Maskell’s status as a priest following the abuse allegations, and the number of plaintiffs in the 1994 civil suit.

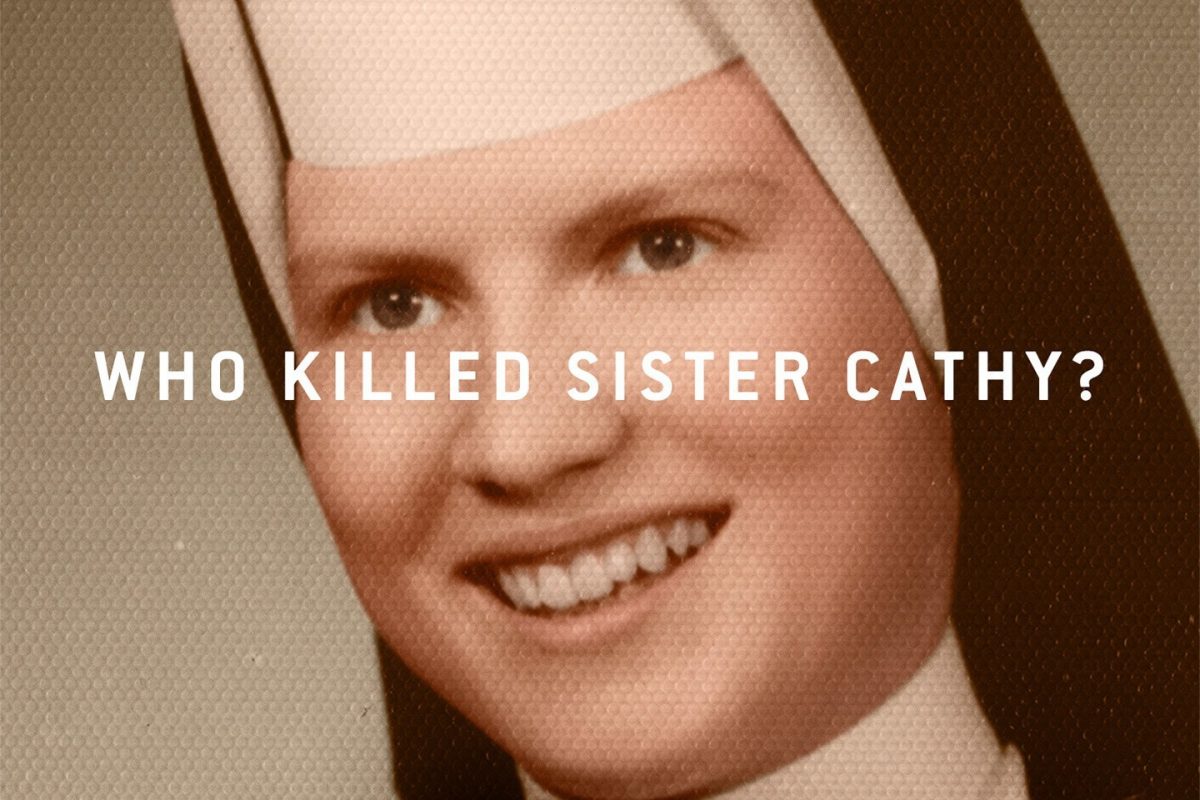

On April 19, the trailer for the new Netflix documentary series The Keepers was released, and since then a heavy foreboding has hung in the air. What, everyone seems to be wondering, will the seven-part series reveal? Its intersecting subjects—widespread sexual abuse at South Baltimore’s Archbishop Keough High School in the ’60s and ’70s and the 1969 murder of Sister Cathy Cesnik, a 26-year-old nun, who many say was planning to reveal the abuse—are about as explosive as can be.

For its part, the Archdiocese of Baltimore spent the week trying to get ahead of what it acknowledges is an unfavorable portrayal in the series. The church is represented in the documentary only through its answers to six written questions submitted by the filmmakers. Archdiocese spokesman Sean Caine admits the archdiocese declined filmmakers’ invitation to appear on camera, but insists that there was no nefarious motivation behind the decision. In fact, he says church officials would have welcomed the opportunity to participate in a more robust written correspondence. “I have my doubts about why they would not have had more questions for us,” Caine said Friday morning, after staying up all night to watch the series. “There was certainly a lot presented in the documentary that warranted additional questions that would have given us an opportunity to provide additional context for it. So I’m disappointed that we were given very few questions. Because, at the end of the day, it’s information you want. It doesn’t have to be on your terms. In other words, if you want to put us on camera to try to embarrass us by asking us questions we can’t answer, [we decline], but we’d be happy to research and get back to you.” Caine notes that The Archdiocese has created a microsite addressing the documentary’s release, which includes a FAQs page and a statement from Archbishop William E. Lori that was sent to the archdiocese’s entire email list earlier this week.

Meanwhile, others see the documentary as a validation of the victims and those who have worked to tell their stories. On a Facebook group dedicated to solving Sister Cathy’s 47-year-old murder, Cesnik’s sister, Marilyn Cesnik Radakovic, wrote that, “This is a very difficult documentary to watch, but this documentary is about courage, and I hope this display of courage is felt by all that view this.”

In any case, the wait is now over. As of 3:01 a.m. today, The Keepers is available for streaming. Before you watch though, here are some things to know.

1. This Has Been a Long Time Coming

Though Cesnik’s murder and the abuse scandal at Archbishop Keough have gone decades without the kind of international attention this series brings, these are not unknown events. Cesnik’s disappearance was front page news in November 1969, and made headlines again when her body was recovered from a secluded industrial area in Lansdowne in January 1970. After that, however, the trail seemed to grow cold and her death—from blunt force trauma to the head—was theorized to have been the result of a robbery gone wrong. But her memory lived on with her pupils. Over time, her death became something of an urban legend at the all-girls school, which was renamed Seton-Keough High School in 1988 and will close in June 2017 due to declining enrollment.

2. The Story Was Kept Alive by a Dedicated Few

Cesnik’s murder investigation heated up again in the ’90s when two women—both Archbishop Keough alums—brought a $40 million lawsuit against the Archdiocese of Baltimore and a priest named Father A. Joseph Maskell. The suit claimed that the plaintiffs had been subjected to physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, and that the church had covered up Maskell’s depravity. Furthermore, the lawsuit alleged that Maskell had been joined in the abuse by other clergy, police officers, a local gynecologist, and at least one politician. The plaintiffs were then known only as Jane Doe and Jane Roe, but the women have subsequently revealed themselves to be Jean Wehner (Doe) and Teresa Lancaster (Roe). Attorneys for Wehner and Lancaster located more than 30 people—both men and women—who were willing to testify against Maskell in the suit. Read more about the lawsuit in the award-winning 1995 Baltimore magazine article “God Only Knows”.

In the mid-’90s, headlines about the lawsuit sparked the interest of two other Keough alumnae, Gemma Hoskins and Abbie Fitzgerald Schaub. Though neither experienced any abuse themselves, they were moved by the stories of the victims and the memory of their late teacher. With help from numerous others, they began conducting their own unofficial investigation. Several years ago, the duo began a public Facebook group, which recently surpassed 1,000 members. They also run a website where people can submit anonymous tips.

These four women—Wehner, Lancaster, Hoskins, and Schaub—will be at the center of The Keeper‘s narrative.

3. The Lawsuit Was Dismissed, But The Archdiocese of Baltimore Has Since Compensated Victims

The lawsuit was dismissed in 1995 after a judge ruled that the suit had been filed outside the statue of limitations for juvenile abuse cases. (Wehner maintains that she only recovered memories of her abuse in the early ’90s, long after the statute of limitations had expired. Lancaster and many other victims say they always remembered their abuse but were too scared to go public. This spring, Maryland extended, from age 25 to age 38, the length of time victims of childhood abuse have to sue offenders.) Father Maskell was interviewed by police and had his priestly powers revoked by the archdiocese in 1994, but he was never charged with a crime. Before the civil trial could start, however, Maskell quietly moved to Ireland, where he found work as a psychologist, sometimes even treating adolescents. According to the archdiocese’s FAQ, “the Archdiocese learned in 1996 that Maskell was living in Ireland . . . [and] informed authorities in Ireland about Maskell’s history and attempted to contact Maskell in writing on numerous occasions.” Maskell eventually returned to the Baltimore area, where he lived in archdiocese-affiliated facilities until his death in 2001. Beginning in 2002, his name was added to a list of clergy credibly accused of abuse published on the archdiocese’s website. In addition, the Archdiocese acknowledges it has paid “over $97,000 in counseling assistance and over $472,000 in direct financial assistance to those who may [have] been abused by Maskell,” including Lancaster and Wehner.

4. Sister Cathy May Not Be the Only Murder Victim

It seems likely that the series will delve into theories connecting Cesnik’s murder to the death of three other women: 16-year-old Pamela Lynn Conyers, whose body was found in Anne Arundel County in 1970; 16-year-old Grace Elizabeth “Gay” Montanye, whose body was found in 1971 in South Baltimore; and 20-year-old Joyce Malecki, who disappeared just days after Cesnik and whose body was found in Fort Meade. Because Malecki’s body was discovered on federal property, the FBI had jurisdiction over the case. It is unclear, however, if the FBI investigated the case at that time. Maskell knew the Malecki family because they were parishioners at St. Clement Church in Lansdowne, where he lived and ministered for a time in the ’60s and ’70s. With the permission of the Malecki family, Schaub filed a Freedom of Information Request in August of 2014 for all files related to a 1994 FBI/Baltimore County homicide joint task force into Malecki’s death. So far, Schaub has received no files, but did receive a reply from the FBI in April stating, “Your request . . . is . . . still awaiting assignment to a disclosure analyst for processing. The current estimated date of completion for the request is October 2017. However, given our current workload and staffing levels, it may be a very long time before you begin to receive material from this request.”

5. Maskell’s Body Was Exhumed In February For DNA Testing

In dramatic fashion, news broke on May 4 that Maskell’s body had been exhumed from a Randallstown cemetery in February and that DNA samples had been taken from it that would be compared to physical evidence from Cesnik’s murder scene. Then, this week, barely 48 hours before the premiere of the documentary, test results revealed that Maskell’s DNA did not match DNA found at the crime scene. “For now, we’ve pretty well reached the end of the road when it comes to forensic evidence,” Baltimore County police spokeswoman Elise Armacost told The Sun. “Our best hope for solving this case at this point lies with the people who are still alive. And we hope that someone will be able to come forward with conclusive information about the murder.”

Anyone with information about Cesnik’s murder is encouraged to contact the Baltimore County Police Department’s Homicide Department, Unsolved Case Squad. Information about the murder of Joyce Malecki can be submitted to the FBI’s Baltimore field office.