Arts & Culture

Variations on a Theme

Local institutions make classical music accessible—and relevant—in the 21st century.

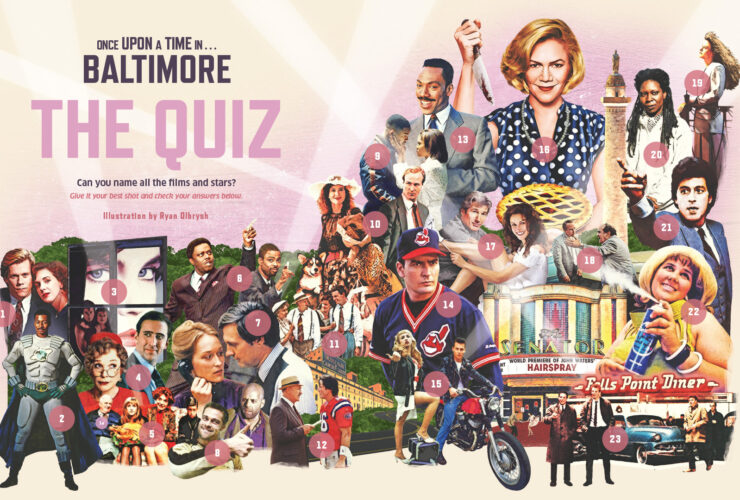

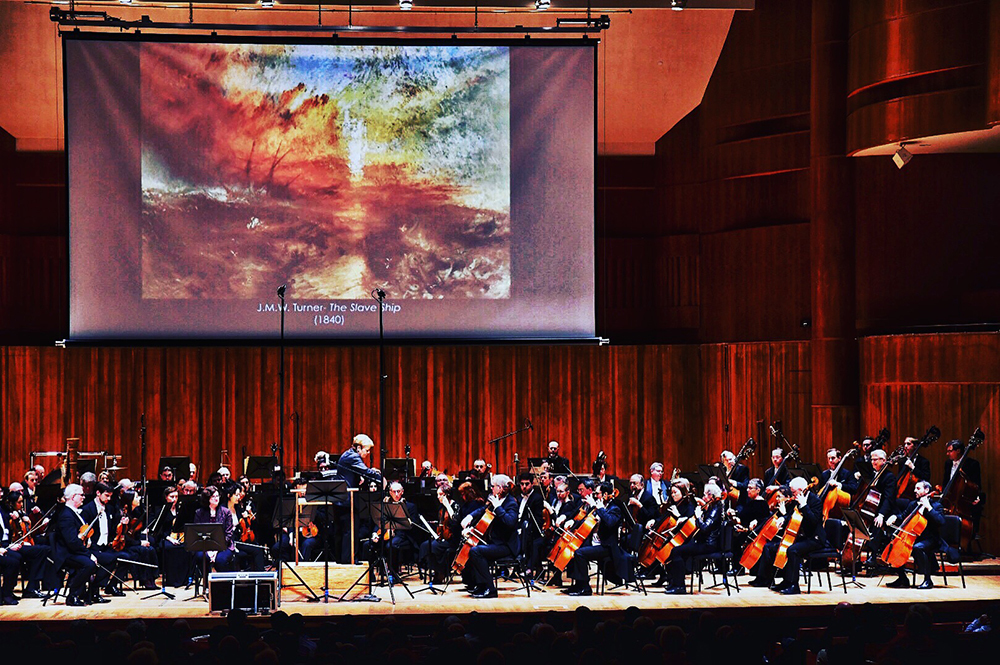

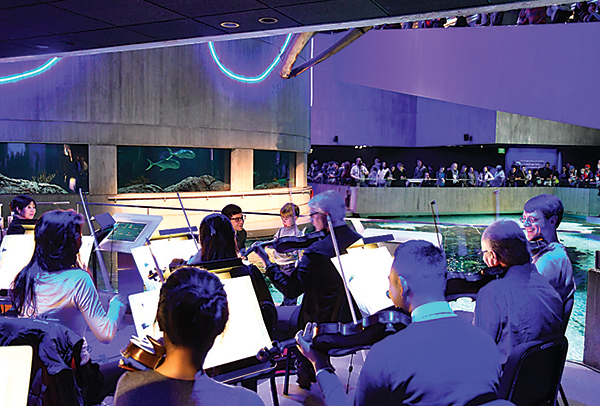

IT’S A SATURDAY AFTERNOON in February, and the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra musicians are performing Handel’s Water Music for a modest crowd. The conductor, concentrating fiercely, bounces her baton in time, while violinists and French horn players occasionally glance up from their sheet music to meet eyes with her.

IT’S A SATURDAY AFTERNOON in February, and the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra musicians are performing Handel’s Water Music for a modest crowd. The conductor, concentrating fiercely, bounces her baton in time, while violinists and French horn players occasionally glance up from their sheet music to meet eyes with her.

She’ll certainly have a story to tell her friends at the playground next week. You see, this conductor is no older than 10, and the ensemble is not performing at the Joseph Meyerhoff Symphony Hall but amid a world of glimmering turquoise waters and corals at the National Aquarium.

Though a seemingly unusual scene, unusual is becoming the norm for many classical musicians in Baltimore. In an attempt to draw in more diverse audiences and a new generation of musicians, groups such as the BSO, Peabody Institute, Baltimore School of Music, and others have paved new ways to lure listeners to the music—whether it’s pairing it with yoga, performing pop-up concerts in public, playing new works by underrepresented composers, or collaborating with hip-hop artists. In the case of BSO’s show at the aquarium, visitors were invited to act as guest conductors to see what that feels like.

Classical music is timeless—that much has been proved—so musicians and administrators are banking on the fact that it’s the culture that keeps many potential listeners at a distance.

Performances did not always conjure up images of formal attire and etiquette—musicians wearing coattails and white bow ties for daytime concerts, black bow ties at night.

Experiencing classical music was not always seen as rigid or potentially dull. Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring and accompanying ballet choreography were met with riots during the work's Paris premiere in 1913. To this day, audiences in Italy still freely boo during concerts. And it’s no secret that Mozart would write raunchy lyrics to his compositions to be performed at parties (his “Lick me in the arse” canon in B-flat major comes to mind)

Symphony attendance has been dropping across the country for decades, although some local initiatives show promise. Attendance for BSO’s Off The Cuff series, for example—which includes an informal talk with BSO music director Marin Alsop, a condensed concert format, and an after party—has increased by 46 percent since it began in 2008, and nearly 40 percent of those ticket buyers are under the age of 40. Its Pulse series, launched in 2015, consistently attracts young audiences.

Several people are determined to push this music forward into the 21st century. And the goal is not to merely make it more accessible. After all, in the digital age, music—and pretty much everything—is accessible at the touch of a screen. Rather, musicians are striving to create doorways into the music so that they can enlighten us as to why it’s still vital and relevant while creating the next generation of lifelong music fans.

BSO at the National Aquarium. valerie june, backed by the bso at a pulse show.

BALTIMORE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

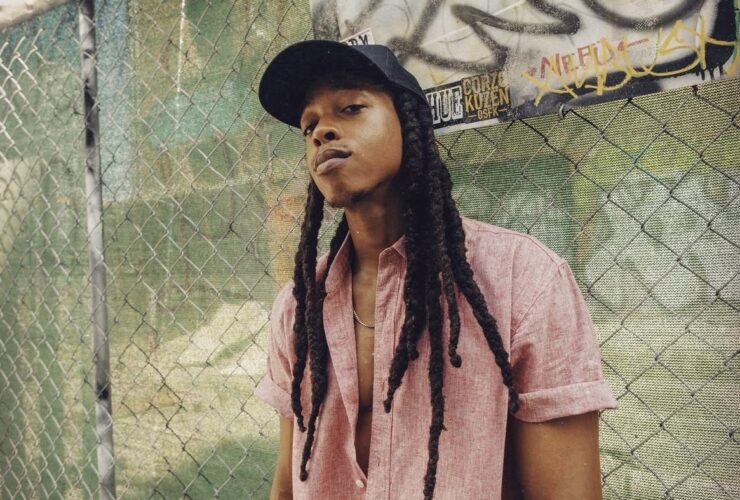

When the BSO performs Tchaikovsky’s “Souvenir de Florence” at the Meyerhoff in March, they’re essentially acting as the opener for Valerie June, who then takes the stage in a showy red dress, dreadlocks piled on top of her head, and belts out her soulful Appalachian vocals over guitar and banjo. But then something even more interesting happens: In a third and final set, June is backed by the BSO, which plays full arrangements of her songs in a magical collaboration.

In partnership with 89.7 WTMD, BSO’s Pulse series is conducted and co-curated by BSO associate conductor Nicholas Hersh, who has given a lot of thought to how to make classical music more palatable for his generation, the millennials.

It started as an experiment: pair a classical piece with an indie artist—not necessarily a piece that fits snugly, but something related by general sound or feeling. For example, June is a passionate, wear-your-heart-on-your-sleeve kind of singer-songwriter, so Hersh looked for a composer of similar essence. The idea is that people will come for the indie act and in so doing might discover a classical piece.

“I think a lot of people like classical music—they just don’t know it,” says Rafaela Dreisin, audience development manager at the BSO and co-founder of Classical Revolution. “We’re trying to be flexible.”

Peabody students at The Johns Hopkins Wilmer Eye Institute;

PEABODY CONSERVATORY

Peabody in Mount Vernon is the oldest music conservatory in the U.S., and it prides itself on keeping tradition alive and training musicians in a manner that’s tried and true.

But in recent years, staff and students alike have found ways to extend their reach beyond the walls of the prestigious institution, challenging the very idea of what a conservatory is.

“Conservatories have not done a particularly good job on rethinking how we train our students for a landscape that is constantly evolving in the 21st century,” says Fred Bronstein, who became dean in 2014. “It’s really important for them to be part of the community and be an asset.”

One way students have done this is through mini concerts in unexpected places—a water taxi, City Hall, even right on the sidewalk.

“Classical music expresses the same love and hate and anger and calm—the same emotions” as other genres of music, says Peabody Conservatory student Yoshi Horiguchi. “This informality allows us to carry on the music without the restrictive culture. It gives an accessibility to people who can’t afford tickets. And it’s a different feeling. Outside, I can walk around with my bass and weave through the audience. And it’s nice to follow up with conversations with people.”

Content has pushed tradition, too. In February, Peabody Chamber Opera performed Out of Darkness: Two Remain, based on the true stories of two unlikely Holocaust survivors—a homosexual Protestant man and a political prisoner who hid her identity.

Also new: An online music tech class that prepares students for ways in which technology can enhance their careers and Wendel Patrick’s hip-hop class, where students learn the history of the genre and work on their own material.

Darin atwater, founder of soulful symphony

SOULFUL SYMPHONY

As Darin Atwater, an accomplished Baltimore-based conductor and pianist, moved through the world of classical music, he began asking himself why American symphonies weren’t really dealing with our country’s native music, and why our classical music is still so very Eurocentric—from Mozart’s Austrian folk themes to Tchaikovsky’s Russian folk music. Why were we not looking to jazz and hip-hop and gospel and blues?

In 2000, he took it upon himself to form an orchestra of predominantly African-American and Latino members dedicated to performing American music. Though he had no point of reference because there weren’t—and still aren’t—any other groups like it, Atwater founded Soulful Symphony, which is now 85 members strong.

Their original compositions showcase rhythmic songs with a vibrant brass section and gospel choir vocals. In 2007, Atwater led the group in a hip-hop symphony.

“The future of classical music in America is going to have to confront this music eventually,” Atwater says. “It’s the music of our native tongue.”

Classical guitarist James Lowe at Sherwood Gardens.

BALTIMORE SCHOOL OF MUSIC

James Lowe has three degrees in music, lives and breathes it, but still gets bored at formal orchestral concerts. He knows how insular that world is.

He started the Baltimore School of Music in 2012 to give all ages the opportunity to learn to play classical music in a casual, non-competitive environment. Instructors aim to find ways into the music that are fun and engaging. For example, Lowe played the beginning of The Beatles' song “Blackbird” to show students that it was derived from the 1700s classical piece “Andante in G” by Ferdinando Carulli, which they then learned.

Students also perform in unconventional places—for example, alongside a yoga class at Sherwood Gardens and, this month, at Monument City Brewing Company, right next to the fermenters.

SYMPHONY NUMBER ONE

Symphony Number One is a chamber orchestra that formed three years ago to showcase substantial new pieces through performances, typically at churches in Baltimore, and live recordings.

“It’s important to record it. It helps the composers,” says music director Jordan Randall Smith. “It’s not like a painter who just needs a canvas. They need the orchestra.”

Smith is mindful of including underrepresented, diverse artists.

“It’s appalling how with many major orchestras, you won’t see a single woman composer in 30 or 40 weeks of shows,” he says. “That, to me, is not acceptable.”

Symphony Number One performances often include a piece by a traditional composer—a dead white guy, as Smith puts it. To some, this is like eating your vegetables before dessert. But when they do indulge in that contemporary piece, it’s often surprising and full of flavor.

Classic Revolution performs.

CLASSICAL REVOLUTION

Peabody alumnae Rafaela Dreisin and Stephanie Ray started the Baltimore chapter of Classical Revolution, a casual open mic for classical musicians to gather and perform at nontraditional venues. Duos and small ensembles—on strings, wind, and brass—play chamber pieces new and old, then wrap up the evening with a jam. Sometimes there are opera singers. Sometimes hip-hop artists join in. Sometimes people just show up and courageously sight-read.

“I take the approach of being fully immersed,” beatboxer Shodekeh, cultural ambassador of the collective, says about freestyling to complicated time signatures. “The slightest movement—you have to sync up with it, anticipate it. I watch micro-expressions in the face, changes in their breathing.”

Ray says they try to push their own boundaries. “We want to show people that it’s not so serious all the time.”

Their first event, at the now-defunct Bohemian Coffee House in 2011, was packed, and they’ve gone on to host gatherings at Joe Squared, The Windup Space, The Reginald F. Lewis Museum, and The Bun Shop, to name a few. One was simply a Spotify playlist listening party at The Crown.

In February, they partnered with WTMD to perform in a live broadcast that featured classical instrumentation alongside electric guitar and beatboxing. “We had people screaming in the audience,” Ray says. “Classical musicians don’t usually get that kind of reception.”

MIND ON FIRE

Mind on Fire, a chamber orchestra "family" of about 18 players led by James Young, formed in 2017 to perform music by diverse living composers.

In their short time together, they've made music with and performed alongside over 50 artists-somatic artists, poets, puppeteers, actors, filmmakers, and a large array of musicians, including Dan Deacon at his 10th Anniversary Spiderman of the Rings show last fall.

On May 19, they'll premiere Brooklyn-based composer Elori Saxl Kramer's work for orchestra and electronics "The Blue of Distance" at EMP Collective.

THE EVOLUTION CONTEMPORARY SERIES

Composer and Peabody Institute faculty member Judah Adashi founded the Evolution Contemporary Series in 2005 and serves as its director. He's presented work by more than 75 composers and has featured world-renowned guests.

In its current season, the series has showcased composer, singer, and pianist M. Lamar's multimedia song cycle Funeral Doom Spiritual, a radical exploration of the African-American spiritual tradition, as well as chamber works by Bryce Dessner, the guitarist in The National.

Concluding the season on May 8, Baltimore artists including Adashi, Outcalls, Joy Postell, The Witches, Ellen Cherry, Brittani McNeill, Shodekeh, and Sophia Subbayya Vastek will perform from the 2017 release Bjork: 34 Scores for Piano/Organ/Harpsichord & Celeste in a concert they're calling The Björk Songbook at An Die Musik. "The concert will honor the voice-plus-keyboard arrangements created by Björk and her collaborator Jonás Sen," Adashi explains, "while leaving space for these extraordinary local artists to bring their own interpretive instincts to bear on the music."

BALTIMORE GAMER SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

What better way to get the kids hooked on symphonic music than through video game themes?

Musicians in the Baltimore Gamer Symphony Orchestra, which runs through the Baltimore County Department of Recreation and Parks, are able to join without auditioning and play to have fun, usually performing publicly twice a year.

"It's a really safe environment for blooming musicians or rusty musicians," says founder and director Kira Levitzky, who finds video game songs online and arranges the music herself.

The orchestra bridges a gap between classical music and popular culture. The music is a means to escape, like a video game itself, she says. "When you play a video game, it becomes your world, and you are part of the story."

IN THE STACKS

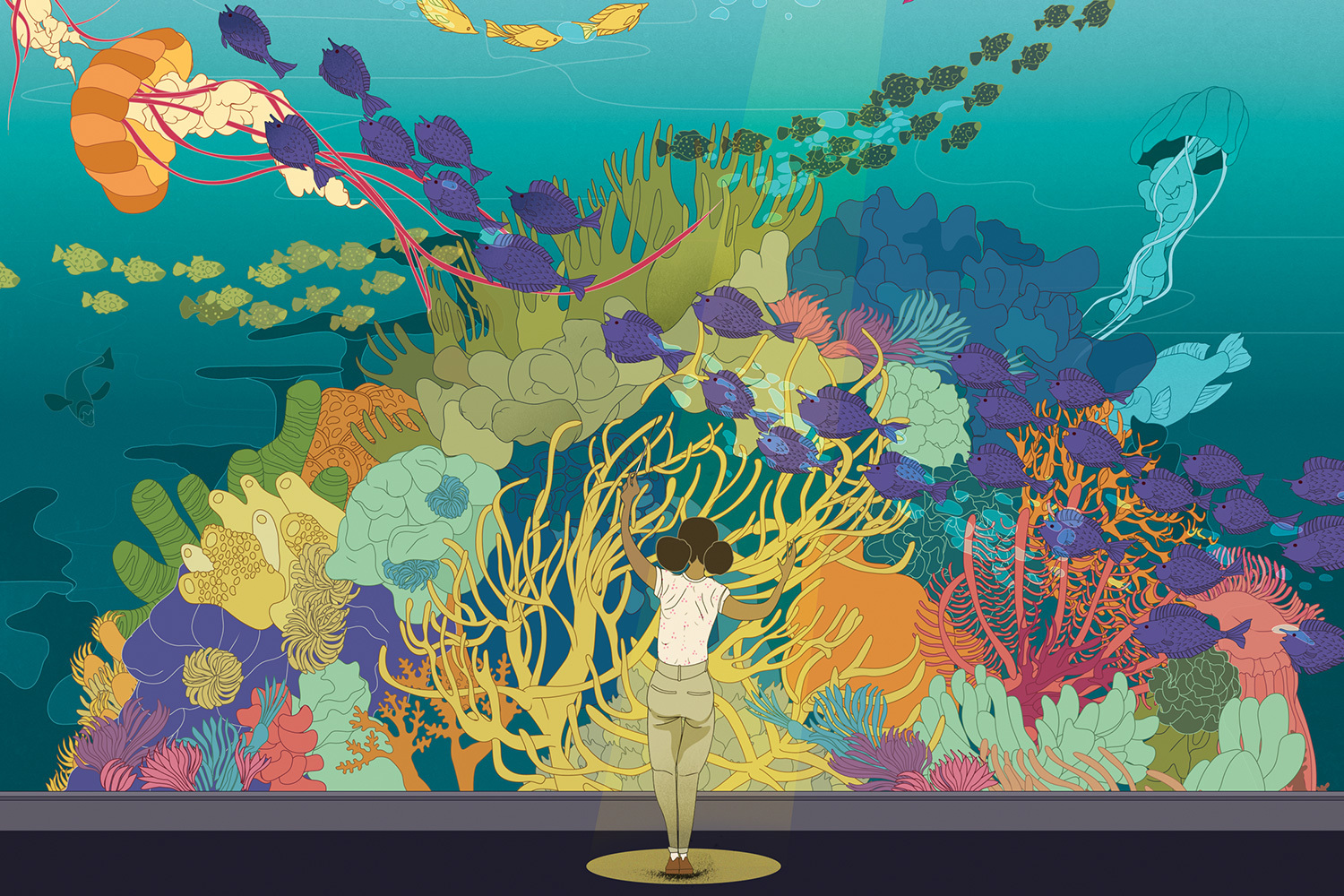

Music in the Stacks was born in 2017 when Peabody students planned a free, after-hours show inside the George Peabody Library. They worked in some talking points and interactive elements, wanting to engage with their audience, and catered the program's content to tie into the library itself.

They were hoping for 50 to 70 people to show up; they ended up ushering in a few hundred.

A second show proved to be just as successful.

"Every time I've played in orchestras, I've felt like there's a disconnect between the audience and performers," says Sam Bessen, 25, founder and artistic director of the series and a 2017 graduate of Peabody's master's program. "Being [Peabody] students, we thought that library had a lot of potential. It's just such a beautiful room."

Those first two shows were a trial run, used to gauge community interest. When it returns for an official season, tentatively beginning this summer, the series will be called, simply, In the Stacks, opening up performances to additional artistic disciplines (drama, art, dance, film, etc.).

As before, the shows will be held during the library's off-hours and admission will be free, though a $10 donation is suggested to pay the musicians.

Bessen is already brainstorming a theatrical production whose stage might be on various library levels, or live music played as the score of a silent film screening.

Scenes from the Occasional Symphony.

OCCASIONAL SYMPHONY

Occasional Symphony has made it part of its mission to bring classical music "out of the concert hall and into the city," says its board president, Elisabet Pujadas. They find intriguing venues and settings to house their concerts.

She is most proud of their Halloween shows at 2640 Space. At these flagship events, the orchestra and audience members come in costume for a screening of a black-and-white horror film set to a score that combines classical pieces with those by contemporary composers. The next one is slated for Oct. 31, 2018.

Since their founding in 2012, they've also hit the Port Discover Children's Center, Mari Luna Bistro, and the Turner Auditorium on the campus of the Johns Hopkins Hospital.