Arts & Culture

Or stories, really—as one can become many.

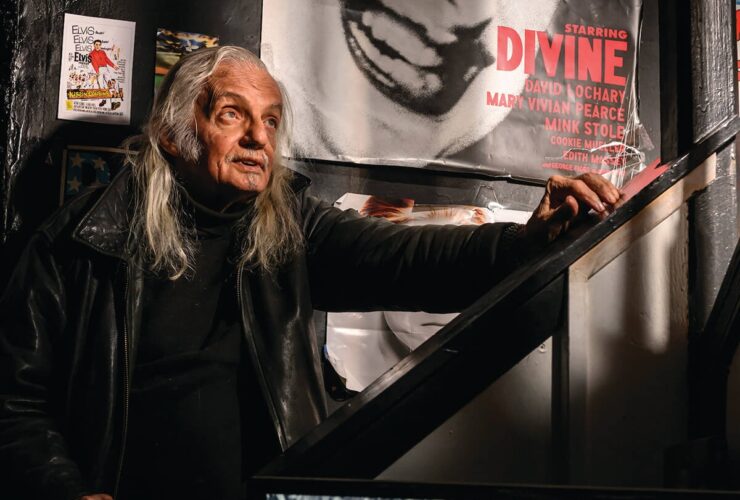

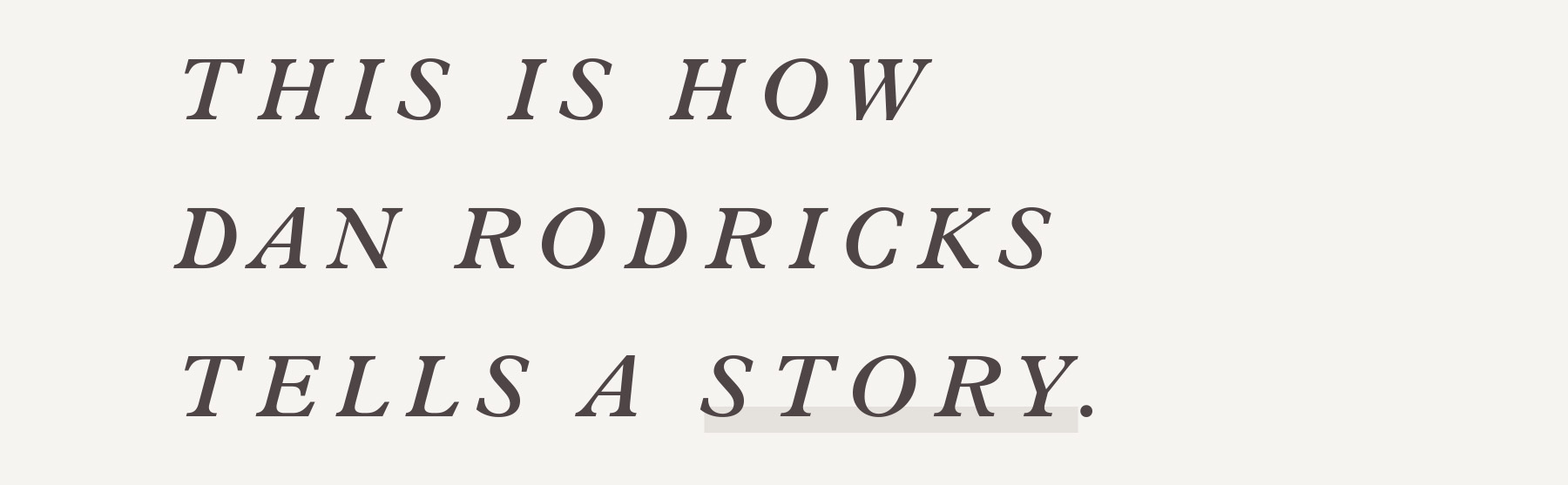

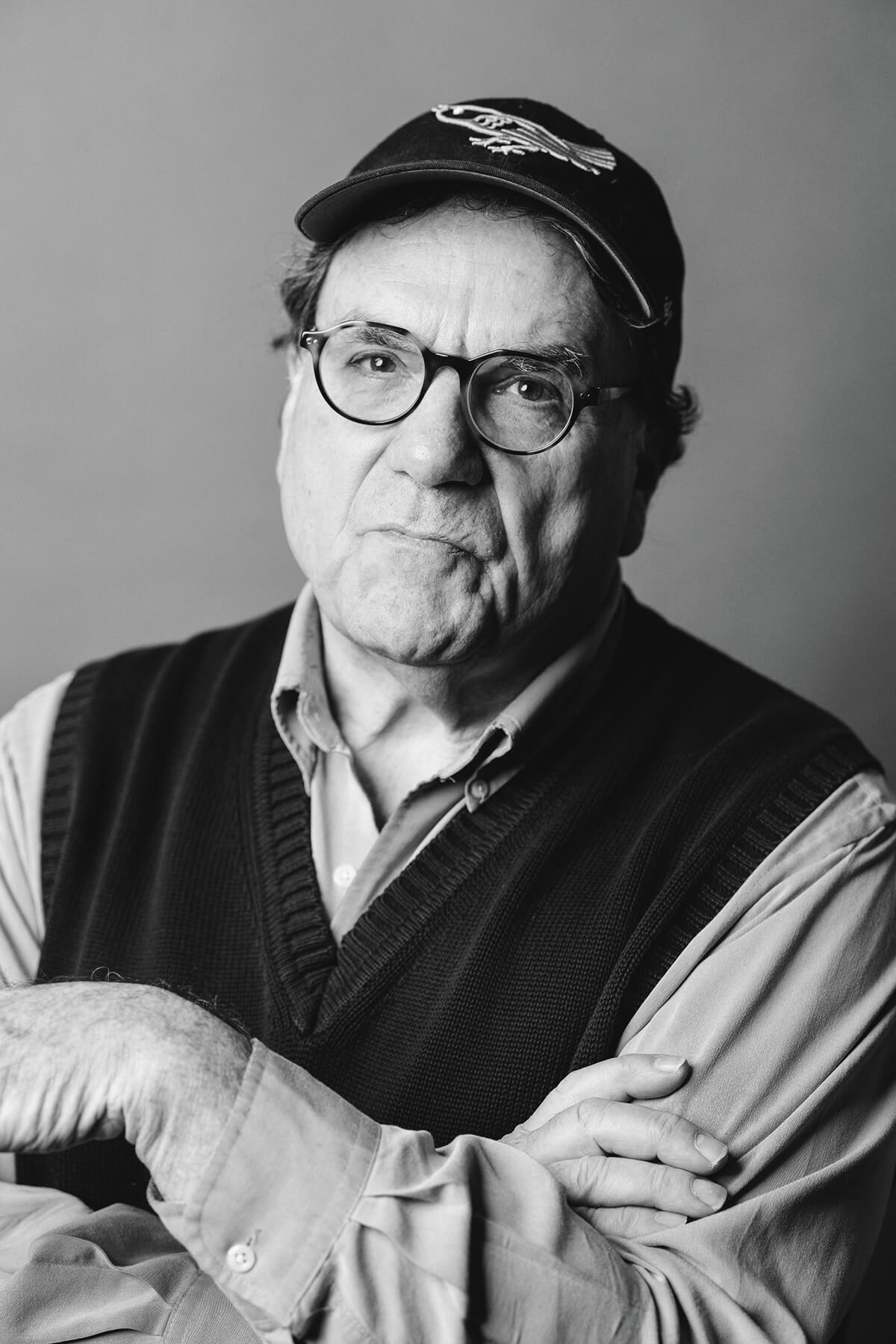

It’s a November morning in his Cedarcroft living room. He’s sitting in a butter-yellow armchair, throwing his head back, letting out a hearty laugh, recalling an ironic anecdote from years ago. A little later, he’s looking off, almost lost in thought, reflecting on some turn of events that recently moved him. There are long pauses, winking wise cracks, moments of matter-of-fact seriousness. A smile crinkles across his face. A hand thrusts into the air. He leans in with a raised eyebrow, as if letting you in on a secret.

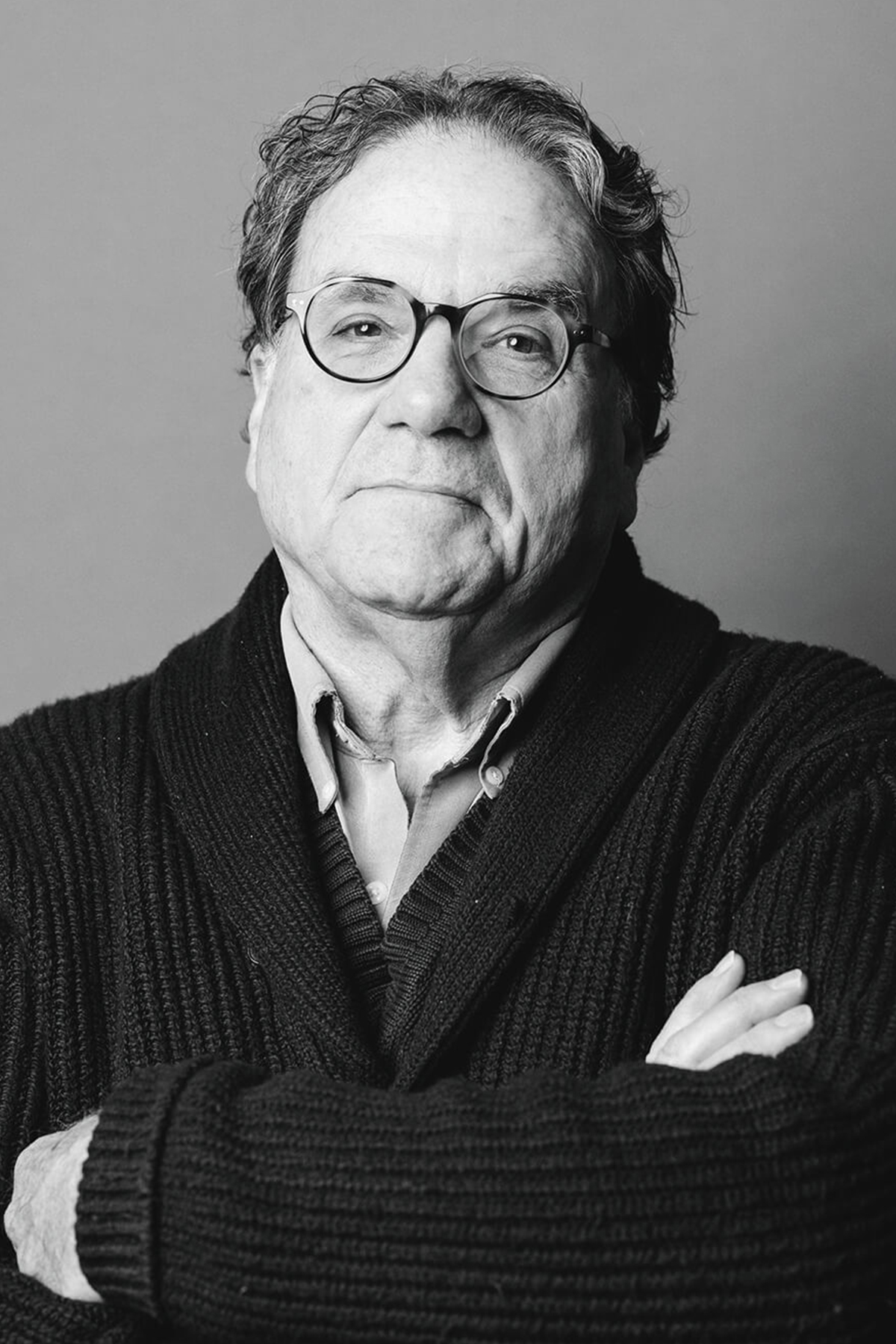

All the while, Rodricks is the picture of a newspaperman, dressed in a V-neck sweater over an oxford button-up, sporting slacks with New Balance sneakers. At 71, he still has a tussle of dark curls, a bounce in his step, and, in a point of pride, a memory that endures like an elephant’s. Which means that all these tales, though seemingly tall, are surprisingly true, and they simply pour out of him—about work, about fly-fishing, about the origins of his dining-room table (more on that later), often featuring a cast of characters that he brings to life with a vaudevillian flair.

There’s the early editor with a booming British accent, throwing the young reporter’s copy into the proverbial trash. (“Dan, deadline has passed!”) Or the Curtis Bay mother he saw on the nightly news, talking in thick Baltimore vowels about a chemical leak that locked down her neighborhood. (“All I know is the police knocked on our door and we were evaporated from the area . . .”) His own Boston brogue only adds to each telling, at times exaggerated for comedic effect. (“This is aht!” he cried during the photographs for this profile.) And if you’re lucky, he might even break out in song, revealing an impressively operatic baritone. (“Yes, I am a pirate king!”)

Of course, Baltimoreans already know Rodricks as a raconteur, be it from the pages of The Baltimore Sun, where for nearly 50 years he wrote one of the longest running newspaper columns in the country before stepping down last January, or on the airwaves of local television and radio, including nearly a decade at the helm of Midday on WYPR. For the better part of a half-century now, they’ve tuned in for his clear-eyed reporting and commentary—exploring the everyday lives of local residents, examining the town’s multitudes, warts and all.

“My rule has always been to balance the dark and the light,” says Rodricks.

Which he certainly has, over the course of some 6,500 bylines. Here are just a few of the topics he’s covered over the long span of his career: the opening of Camden Yards, the closing of Bethlehem Steel, the sinking of the Pride of Baltimore, two Super Bowl wins, the Capital Gazette shooting, the death of Freddie Gray, the collapse of the Francis Scott Key Bridge. Not to mention arabbers, artists, firefighters, fishermen. Bartenders, dirt-bikers, politicians—from William Donald Schaefer and Kurt Schmoke to Sheila Dixon and Brandon Scott. City schools, budget battles, police corruption, crime.

One particularly violent summer, he used his column to call for a ceasefire, offering to help those in the crosshairs get off the streets, even publishing his own phone number. “It started ringing that day and didn’t stop for, like, three years,” says Rodricks, who lost count after 5,000 of them but actually made good on his promise—in what he calls “one of the most rewarding moments of my career.”

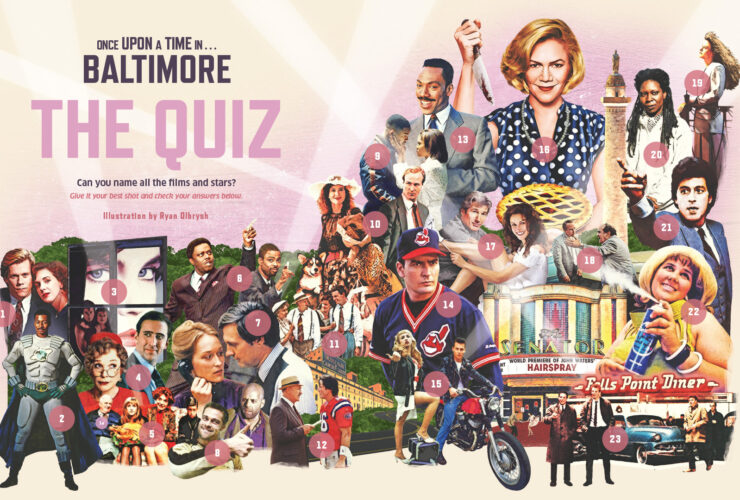

Of course, he’s also written about the films of John Waters. The rise and fall of Harborplace. The charm of Formstone. Or altogether, as one 1979 column put it, “Crabs, Crooks, and Other Stuff.” A bona fide fortune of Baltimore history.

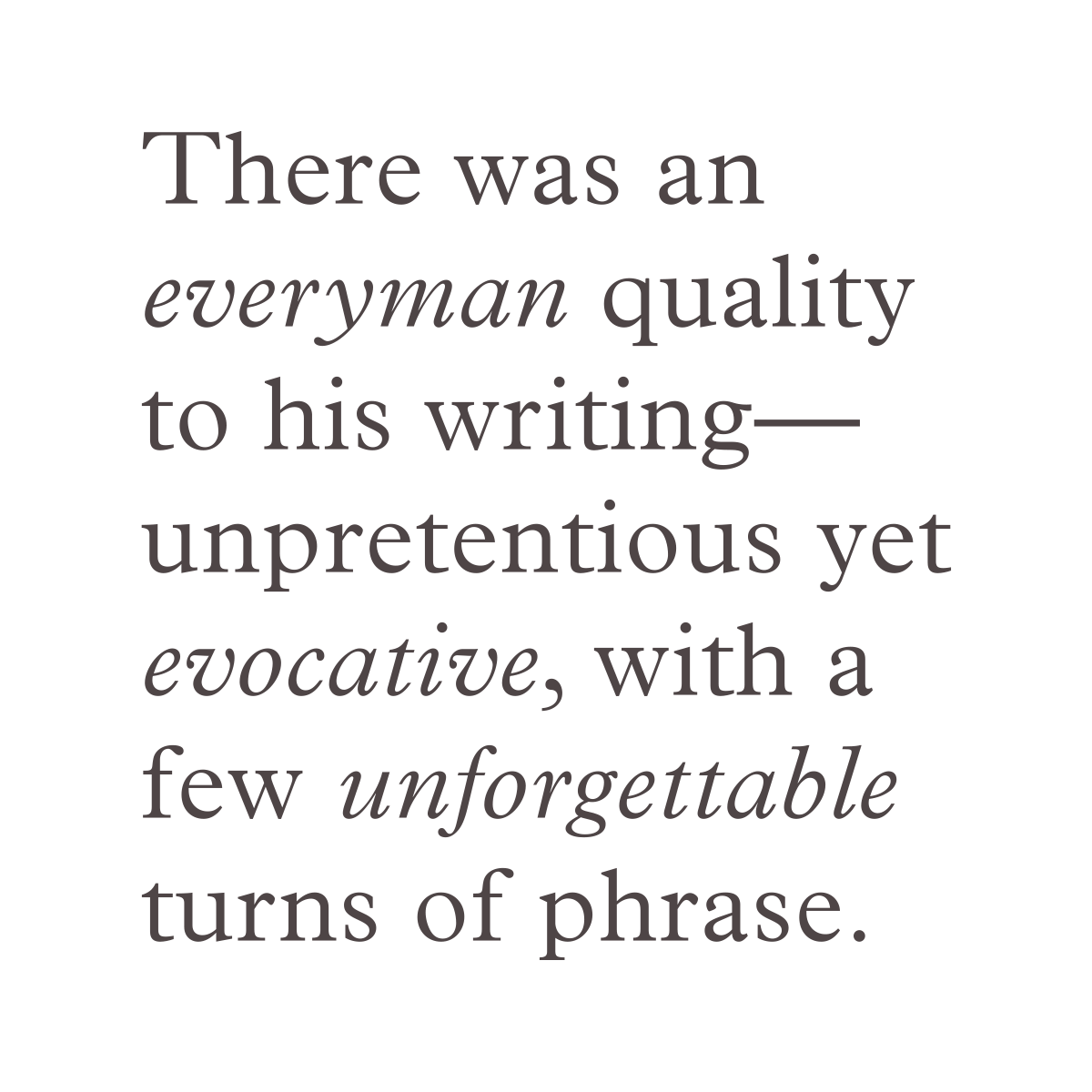

And today, as the sunlight pours into his living room, which doubles as his office, which triples as his library—the bookshelves behind him filled with family photographs, Orioles bobbleheads, and anthologies of great writers like H.L. Mencken, Ernest Hemingway, Charles Dickens, Shakespeare—it’s clear there’s more where that comes from.

“What is it about this city?” he poses, perhaps rhetorically, wondering aloud what kept him here all these years.

Then his eyes light up. He knows part of the answer.

“There are just so many good stories...”

In fact, at his wooden desk, on his Dell computer, an unfinished script waits with a blinking cursor. Rodricks is writing one of them as we speak.

THE MANY FACES

OF DAN RODRICKS,

WHO HAS BEEN

ACTING SINCE HIS

FIRST HIGH-SCHOOL

PRODUCTION OF

FIDDLER ON THE

ROOF IN 1972.

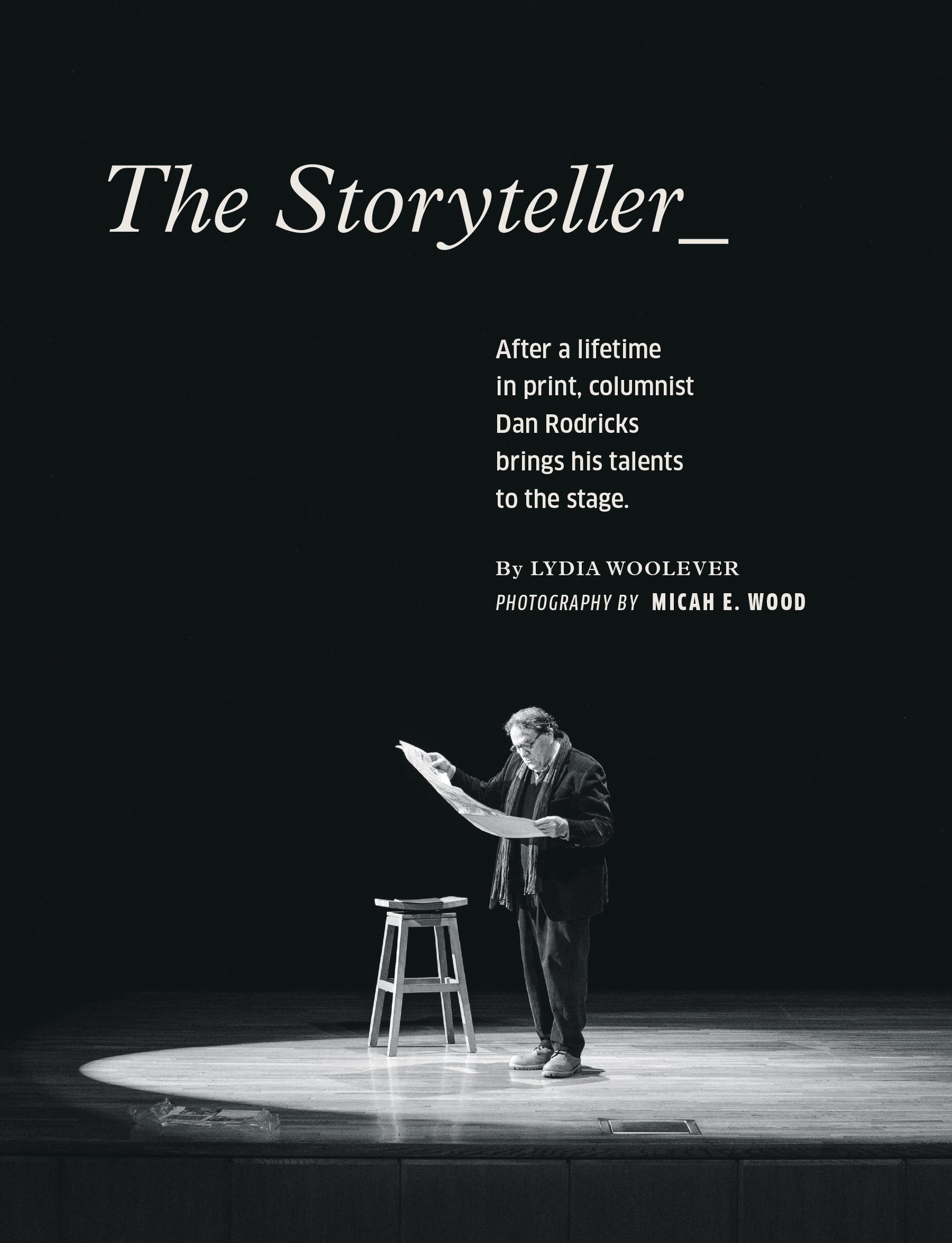

That aforementioned script? It’s not his first foray. Two original plays—Baltimore, You Have No Idea and Baltimore Docket—have already had sold-out runs at the Baltimore Museum of Art’s elegant Meyerhoff Auditorium, which is where his third, No Mean City, is making its premiere this March. But this love of the stage has been a lifetime in the making, really. And it all began back home, in his native New England.

Rodricks grew up on the South Shore of Massachusetts. His father was a Portuguese immigrant who ran a small family foundry—last name originally Rodrigues. His mother, the daughter of Italian Catholics, was largely a homemaker, stepping into factory work when times got tough, also known for an excellent spaghetti and meatballs.

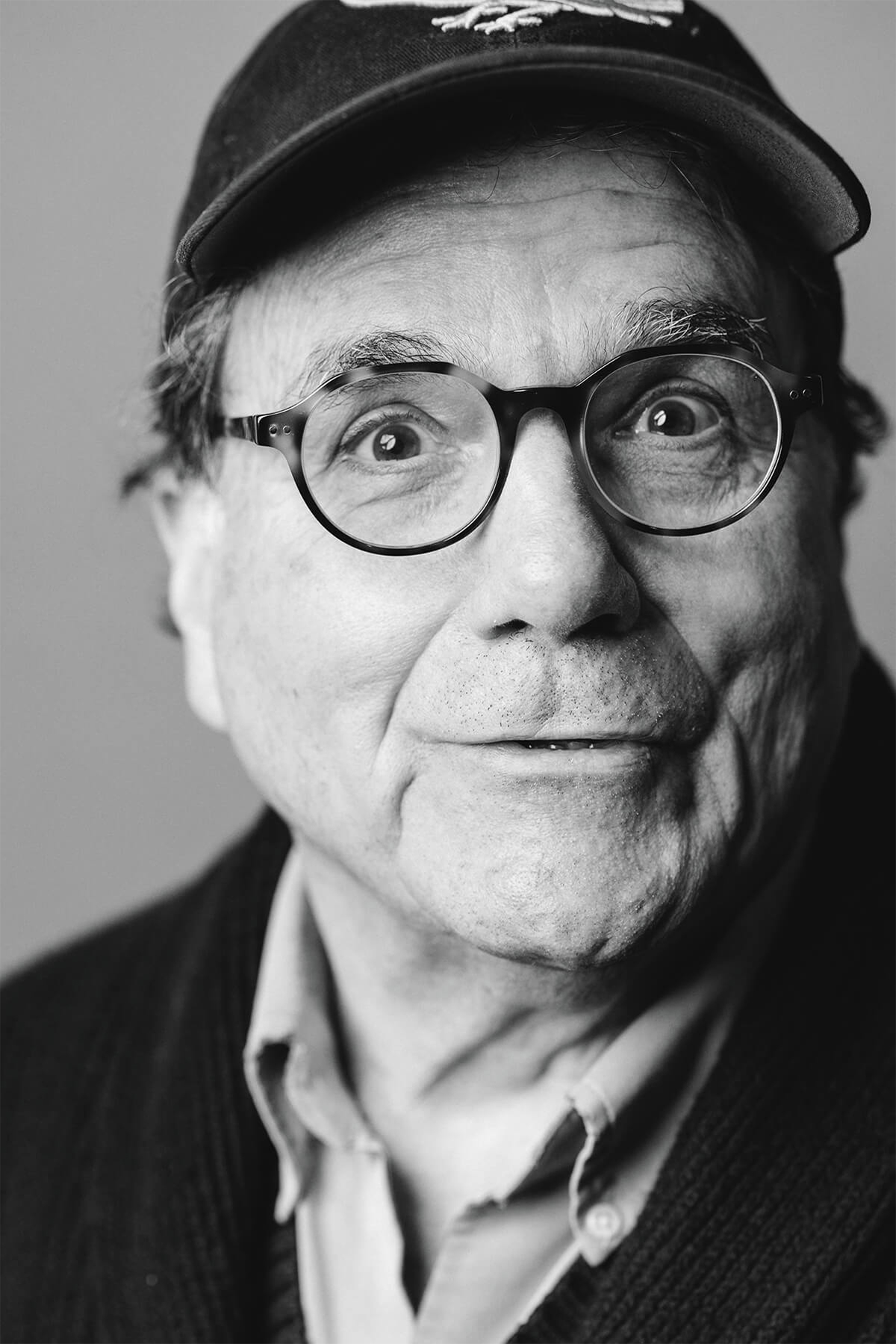

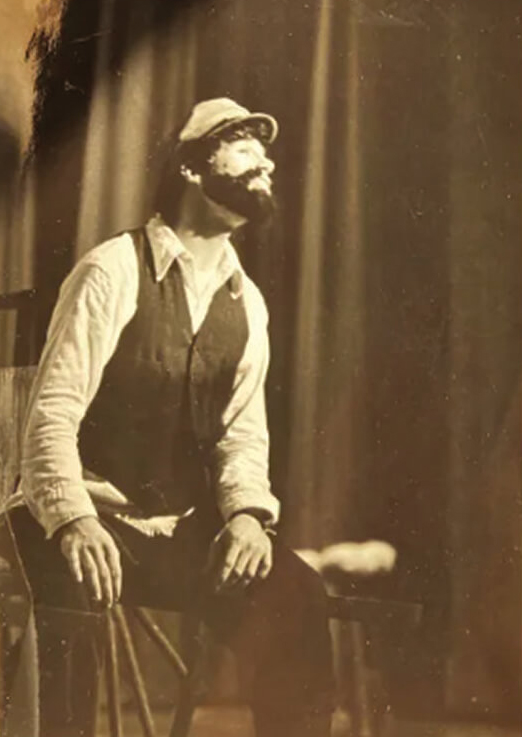

Born in 1954, Dan was the second youngest of four children—an extroverted kid, self-described as a “Type A” but “B student,” and a natural at many things. First, as an athlete, playing football, baseball, and ice hockey through high school. Then his senior year, he got recruited by the drama club to star in Fiddler on the Roof. He spent weeks studying the part of Tevye, listening to the Broadway recordings at the local library, ultimately nailing every line of “If I Were a Rich Man.”

“Get a standing ovation, in high school?” he whispers, seemingly still in disbelief. “Well, that was very exciting.”

At this point, though, his ambitions were elsewhere. Raised with three newspapers on the kitchen table—The Boston Globe, Boston Herald, and Brockton Daily Enterprise—Rodricks had become fascinated with writing. Initially, he wanted to cover sports. But as a journalism major at the University of Bridgeport in Connecticut, working for his college paper and paying tuition through internships at regional dailies, he got turned onto the news.

“There’s nothing like it . . . the adrenaline rush from writing on deadline, being out on the scene where things are happening, learning to ask people questions—it’s the drama of real life,” says Rodricks. This was also the time of Nixon, of Watergate, of the Vietnam War. Back then, all eyes were on The Washington Post, and “Woodward and Bernstein were the superheroes.”

On campus, he also found another infatuation— his future wife, Lillian Donnard. They met at a party through mutual friends. “It was like, where have you been all my life?” says Rodricks of “Lil.” Or as she puts it about her “Danny,” “I saw him and said, ‘He is the single most beautiful human being I’ve ever seen’—I mean, he was really good-looking,” quickly becoming enamored by his smarts and sense of humor, too.

After graduating in ’76, Rodricks followed an internship that turned into a full-time job in Baltimore, where Lil eventually joined him. Back in those days, the city’s paper of record was a house divided, with its Mount Vernon newsroom split between two distinct editions, the morning Sun and the Evening Sun. If you imagine it like Animal House, the former was a buttoned-up Kevin Bacon to the latter’s wild-eyed John Belushi. You can guess where Rodricks landed.

The Evening Sun was scrappy, irreverent, the home turf of heyday Mencken. Here, he started out as a general-assignment reporter, covering the usual circuit: cops, fires, courts, housing, and City Hall. But his aspirations were bigger, being a fan of shoe-leather columnists like New York’s Jimmy Breslin and Chicago’s Mike Royko. You can see it in his earliest bylines—including one about a small-town police chief, who, in trying to recall a notable crime, “wheels back in his chair, squints his right eye, bites his brown cigarette, studies the thought on the tip of his tongue, then gives up.” And yet he was dumbfounded when, out of the blue in ’79, he got his own column.

“I was 24—nobody cared what I had to say, I didn’t have any big opinions yet,” says Rodricks. “So I decided to just find the stories that other people weren’t reporting, and to write them colorfully. It took a while to gain that confidence.”

Slowly but surely, though, with the help of a few hardnosed editors, he found his voice. Three days a week, Rodricks hit the streets, going everywhere, talking to everyone, seemingly about a bit of everything—chronicling the untold stories of Baltimore. A disabled clockmaker repairing watches out of his Carrolton Ridge rowhome. A community elder mobilizing to beautify abandoned blocks in Druid Heights. A boxing-gym owner feeding fired steelworkers near Eager Park. In only a few hundred words, he spoke volumes about this city, always illuminating the underdog and increasingly taking on the powers-that-be, which earned him the national Newspaper Guild’s prestigious Heywood Broun Award for civic journalism in ’83.

Then as now, there was an everyman quality to his writing—unpretentious yet evocative, with a few unforgettable turns of phrase. Take, for example, how he so aptly described Mayor Schaefer as “a man who can look at a broken beer bottle and see an emerald.” Or the way he observed that a future Orioles owner who got arrested for scalping playoff tickets stood out in the courthouse “like an America’s Cup yacht at a Middle River marina.” Dan Fesperman, who started at the Evening Sun in ’84, can recite that one verbatim. “It’s one of his all-time great lines.”

In no time, Rodricks was a larger-than-life presence, both to the public and among his colleagues. “He just brought this energy—you’d be sitting there, working on a story, and every so often you’d hear—I wouldn’t call it a cackle . . . but this really loud laugh, and you’d go, ‘Oh, Dan’s got something,’” says Milton Kent, who joined the paper in ’85. “He’s always been a spirited person. And there’s something to be said for that, especially in what are often staid newsrooms.”

Exhibit A: In 1985, Rodricks’ very first script was for Little Big Paper, a short-film spoof of their factious newsroom, featuring cameos from Fesperman, as well as longtime obituarist Fred Rasmussen and the late photojournalist Irving Phillips Jr. It’s still searchable on YouTube, but that year, they screened it for all the bigwigs during a stately Evening Sun banquet. Publisher Reg Murphy never cracked a smile. “I guess he didn’t find it funny,” quips Rodricks, who was also known to grace the occasional holiday party with a Bruce Springsteen impersonation.

Clearly that theatrical streak never went away for this admitted “ham.” In 1986, he joined the Young Victorian Theatre Company in Roland Park, spending a few summers starring in classic musicals like Pirates of Penzance and H.M.S. Pinafore. And in the back of his mind, he’d already started thinking about writing his own plays. After all, he had plenty of material.

RODRICKS SITTING

AT A DESK IN THE

FRONT LIVING

ROOM OF HIS

CEDARCROFT

HOME, WHICH

DOUBLES AS HIS

OFFICE AND

LIBRARY.

One thing you need to know about him: The man doesn’t sleep. Not much, at least—to his wife’s dismay. His colleagues have been known to receive emails at all hours, his mind always on the move, usually up and at it around 4 a.m.

He approaches a script much like his columns. By now, he knows the basic routine: how much reporting a story needs, how long it will take to write. “The tough part is getting started—that first paragraph,” he says, even after all these years. But once it’s finally on the page, he’ll read his work over and over, however many times feel necessary. For his latest play, No Mean City, he’s been neck-deep in research and newly wrangling with dialogue, which won’t truly stop until the curtain’s raised.

That dedication? “It’s baked in his DNA,” says Lil, a career social worker. “In the early days, he worked all the time. And not like sitting at a typewriter working all the time. Every experience was grist for the mill, so to speak. [Even today,] if we go for a walk in the country, he has to take pictures, or if we meet somebody interesting, he’ll write down their name, because it might be something to come back to. It’s a constant—life and work overlap. Every day is a possible story.”

It’s no surprise then that his theatrical productions have pulled from real life. Truth is stranger than fiction, after all, and “that’s especially true in Baltimore,” says Rodricks. In 2022, his first play, Baltimore, You Have No Idea, debuted as a dramatization of his most memorable encounters as a local journalist—some playful, others poignant, with original music and an all-purpose set, starring the playwright himself as narrator. Its follow-up, Baltimore Docket, employed the same formula in 2024, a collection of courthouse scenes he witnessed firsthand.

He got the idea for this anthological approach years earlier, during an interview with actor Eric Bogosian, who in the early ’90s was hot off Talk Radio fame and bringing a one-man show to Center Stage. Inspired in part by the streets of New York, Bogosian’s masterful monologues shape-shifted between myriad characters—a subway panhandler, a high-powered lawyer, a chain-smoking English rock star—revealing a motley portrait of America. And Rodricks was in awe.

“I kept thinking about it,” he says. “I thought I could do something like it.”

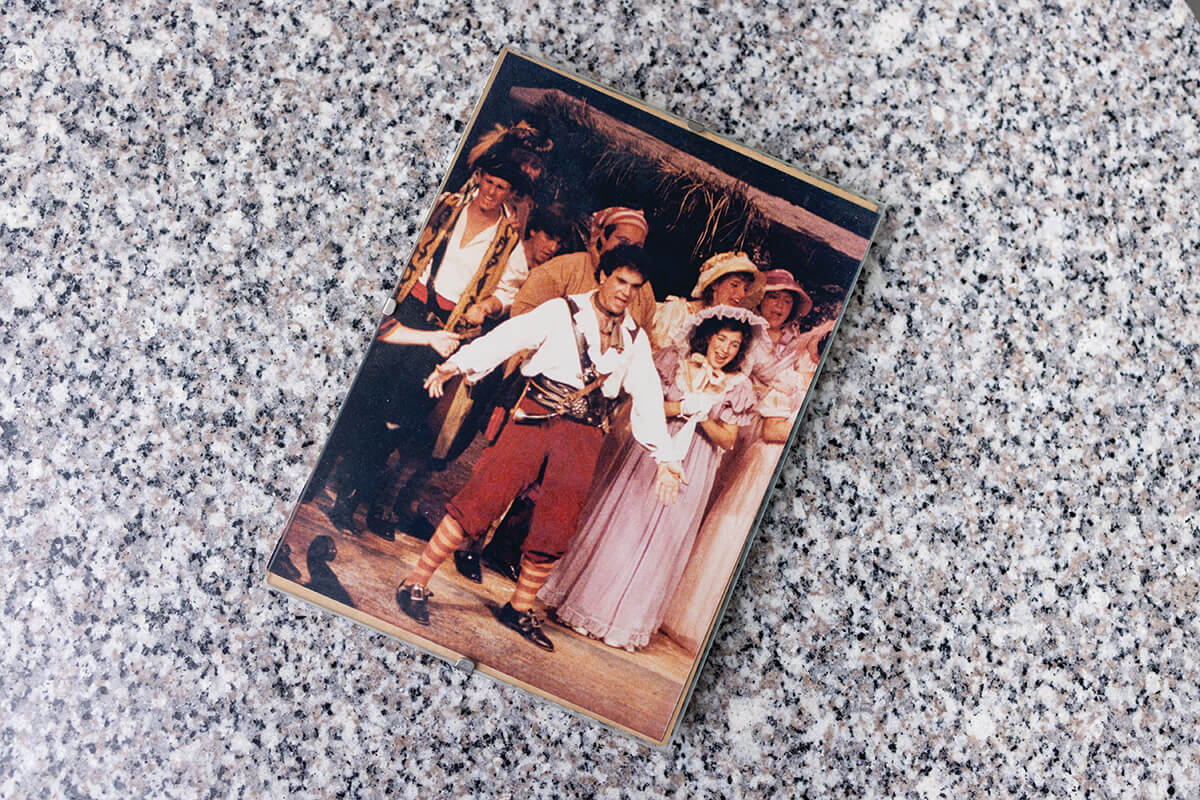

RODRICKS IN

THE YOUNG

VICTORIAN

THEATRE

COMPANY’S

PIRATES OF

PENZANCE,

1986.

Life got in the way for a while. Busier than ever, he was now raising two kids—his son, Nick, and his daughter, Julia. And on top of his ongoing column at The Evening Sun—its two editions soon to merge into a single paper—he’d started dabbling in other mediums, working as a weekly reporter on WBAL-TV, and hosting his own nightly talk show on WBAL-Radio. Within a few years, he was also spending weekends doing Rodricks for Breakfast on WMAR—all the while unknowingly gathering skills for the stage.

“That was probably the hardest I ever worked,” recalls Rodricks of that television show, which needed a large crew to tackle the two-hour live production, featuring variety elements and eclectic guests. Like an 80-year-old bodybuilder from Annapolis who walked on stage in a Speedo to the sounds of Elvis Presley. “B-b-bad to the bone,” sings Rodricks, whose own dog, in tow for a later segment on pet psychiatry, got loose mid-episode, ran in front of the cameras, and sniffed the octogenarian’s crotch on-air. “You could hear me in the background yelling, ‘Katie, come!’”

Then WYPR came calling, asking him to host a new daily public-affairs program called Midday, where, across more than a thousand episodes, he’d cement himself as this generation’s Bard of Baltimore.

“I feel very lucky,” says Rodricks. “And this is very important to me—I didn’t have to leave to have these experiences.” (Though WBZ-TV in Boston did try to woo him once. But that’s a story for another time.)

He shares that same gratitude for his adopted hometown at the end of Baltimore, You Have No Idea— which he calls his “one-man play with a cast of seven,” ultimately enlisting friends from past lifetimes, like his WYPR producer Vanessa Eskridge and Will Schwarz from WMAR (“my rabbi,” says Rodricks). By its premiere, he’d already left the airwaves, finally finding some time to go all-in on theater.

In the play’s closing scene, Rodricks stands alone on stage. He’s telling the audience a personal story about a model train that his mother bought him during a particularly down-and-out Christmas. The toy meant everything to him as a kid, but to his disappointment, it disappeared before his own children were born. Then in ’98, the soliloquy continues, he happened to be in this very same room, about to shoot a holiday special, when a stranger appeared. Through a mutual friend, this man had learned of Rodricks’ loss and, in a twist of fate, as a collector himself, pulled out an exact replica.

Rodricks wells up whenever he tells it—overwhelmed by the generosity of this town, which has given him so much of its time, so many of its stories.

“I guess that’s why I stayed, I guess that’s why I’m still here,” he projects out into the crowd, his voice rising in epiphany.

“So many good people . . . ,” he says, now softly, shaking his head. “I had no idea.”

Then the spotlight cuts, and the audience erupts, jumping to their feet in a standing ovation.

“Dan’s not from Baltimore but he’s of Baltimore,” says Schwarz. “He’s got heart, and also this affection for this city that comes through in everything he does. It’s genuine—and people can tell.”

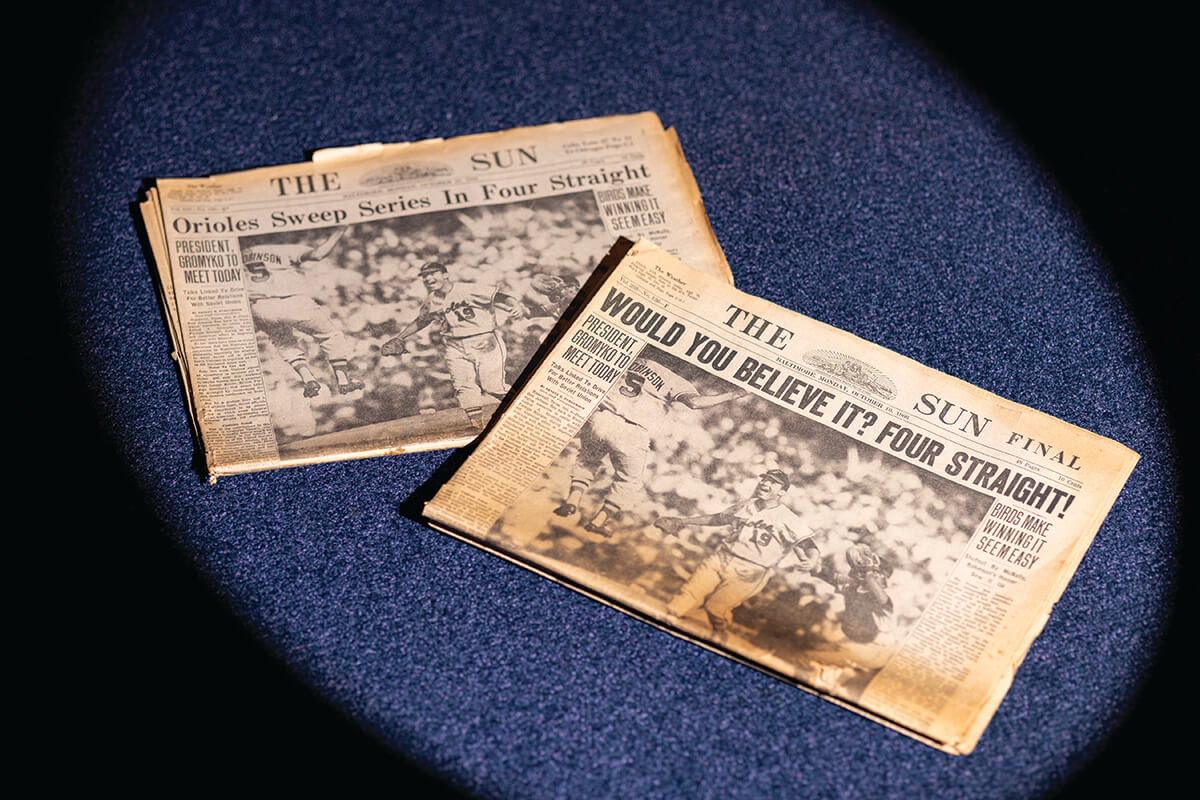

OLD COPIES OF THE

SUN CELEBRATING

THE ORIOLES’ 1966

WORLD SERIES—THE

SUBJECT OF RODRICKS’

NEW PLAY,

NO MEAN CITY.

And he’s both over-the-moon and maybe a little bit nervous about it.

Though also set here, No Mean City is not like his previous plays. Before Baltimore Docket closed, he’d already begun thinking about the next project. This time, he wanted a bigger challenge. So instead of drawing on his past reporting, this would be an entirely new work, with a more conventional narrative, akin to an Arthur Miller or August Wilson plot. No pressure, of course. But he thought he’d stumbled upon a good story—maybe one that has yet to be told.

“If you mention 1966 to anyone in Baltimore who’s old enough to remember, what they immediately think of is the Orioles winning the World Series,” says Rodricks, noting the 60th anniversary this season. “But I was curious, besides baseball, what else was happening in Baltimore that year?”

It turned out to be a critical juncture. At the height of the Civil Rights movement, Baltimore was two years away from a full-blown riot. White flight was at full throttle, shrinking the city by the day, while an uphill fight to end racial discrimination and segregation found an unlikely ally in Republican Mayor Theodore McKeldin. And through it all, there was a tale of two Robinsons: a white third baseman named Brooks and a new Black outfielder named Frank, forging a friendship that would build an all-star team to win the top prize of the greatest sport in American history.

“It’s sort of poetry,” says Rodricks. “You know, I see Baltimore as this crucible. For, can we do this? Can we get over the past? It’s been tough. People ran away from the city. And I always think about would’ve happened had they stuck around longer.”

Fittingly, for this historical drama, he will portray a Sun reporter. But it’s a role that he no longer plays in real life: A year ago this month, Rodricks signed off from his 46-year column at the paper. He saw the writing on the wall under its new owners, which include David Smith of the conservative Sinclair Broadcast Group. Rodricks is worried about the state of this country, and of journalism, for that matter, but not enough to truly retire. Straight away, he started contributing to the Baltimore Brew and Baltimore Fishbowl, also joining Substack, where he covers the national news.

Now he fosters that newsroom camaraderie with his fellow thespians, including his son, who will be co-starring as Brooks. This is not their first time working together—when Nick was at Friends School, Rodricks directed him in his own rendition of Broadway’s The Front Page. Plus, the 35-year-old had smaller parts in his father’s first two productions, also helping out with props and tickets.

“Growing up, you played sports and you did theater—those were the house rules,” says Nick. “I have very fond memories of wiping eye black off from lacrosse games just to put on stage makeup...It’s been great to get this opportunity with my dad.”

AS

TEVYE IN FIDDLER

ON THE ROOF, 1972.

Of his son’s acting skills, “I’m proud of him,” says Rodricks (also quick to compliment his daughter for her exceptional ice-hockey skills). At the same time, he’s careful to avoid favoritism in his plays, treating the cast and crew as part of an ensemble, all held to a similar standard. Everyone gets paid and any leftover profits become start-up money for the next production (the first shows were financed on his own dime). As the showrunner, he operates with both a tireless attention to detail and quick, from-the-hip instincts, relying on only a few trusted confidantes for feedback.

“The world needs its dreamers,” says Lil. “I’m usually the reality check. . . . Like, how much is that going to cost? How long is that going to take? You invited how many people to dinner?”

RODRICKS AND

ESKRIDGE ON

STAGE AT THE

BMA DURING

A SCENE IN

BALTIMORE, YOU

HAVE NO IDEA,

2023.

Rodricks admits that his wife brings some common sense to his bouts of idealism. As does Eskridge, director for No Mean City and head of the new Manor Mill Playhouse in Monkton, who serves as his sort of on-set disciplinarian. She appreciates his gusto, also calling him something of a rarity.

“The world of theater is riddled with big egos that are desperate to remain relevant,” says Eskridge. “Dan definitely has the acting chops to go it alone. . . . But he steps back and asks what’s best for the story. He has this really good knack for seeing the whole picture, and how it’s all going to work on stage.”

As a playwright, Rodricks finds himself thinking in multiple dimensions—lighting, music, stage direction, set design, the syntax on the page, the sound of the words said aloud. “I don't know about you, but when I go to the theater, most people focus on the action and dialogue,” he says, “but I’m always looking around the room,” taking in everything.

Some might call this perfectionism. But to those who know him, it’s actually much simpler. “Dan just doesn’t half-ass anything,” says Kent, who also acted in Baltimore Docket.

To that end, No Mean City is upping the ante. He and Eskridge held real auditions and hired seasoned actors to join those already on Rodricks’ speed-dial. Starting a play from scratch has been a big lift, especially in terms of capturing the spirit of these famous figures he’s never met, from an era he never experienced. To do so, he threw himself into reporting, interviewing former Orioles like Boog Powell, combing through The Sun archives, devouring every bit of information he could find. As has always been true, he cares deeply about getting it right—and also not getting it wrong.

During that standing ovation after Baltimore, You Have No Idea, the entire cast came out to take their final bow at curtain call. Everyone except for Rodricks. It was all too much, even for this natural-born showman. Instead, he slipped backstage, afraid to know what the audience thought, even amidst their deafening applause.

“Then Lil comes barging in, and she’s got this look on her face, and I knew right away,” says Rodricks. “We had succeeded. . . . It was a wonderful feeling.”

“I distinctly remember thinking, ‘Oh my God, he really pulled it off,’” says Lil. “I was completely overwhelmed, and I’m not easily overwhelmed. I’d heard it all 52 times before, but I cried a lot, I laughed a lot. As if it was new to me.”

To this day, the two of them wait until the lights dim and the crowd dissipates. “Once the place is empty,” she says, “we sneak out through the back door.”

Some preparation will happen at his dining-room table. Dating back to the turn of the last century, that big oak behemoth was a longtime centerpiece of the old Sun boardrooms, and Rodricks pulls a black-and-white photograph off his wall to prove it, pointing out Mencken in the back.

After the paper moved from its Calvert Street headquarters in 2018, Rodricks hauled this prized possession up to his Dutch Colonial home in North Baltimore—a physical tether to that venerable lineage. Today, it’s where he proudly hosts his legendary family dinners, holding court every Thursday for an array of “visiting dignitaries,” many from his Sun days, usually with a gaggle of dogs underfoot.

“Nobody gets out of here without hearing about the table,” chuckles Rodricks—a fact that his kids can confirm with an affectionate eye roll.

Here, he also leads his plays’ table reads, with No Mean City’s taking place just after press time. The script is now out in the universe. Tickets are on sale. Rehearsals start this month, which is when the real work begins.

On Rodricks’ desktop, beside a small vase of pink carnations, that other play-in-progress is well underway, and he’s currently in talks about finding it a home at Everyman Theatre. This spring, he’ll also head back to where it all began, performing a new autobiographical work at his alma mater high school, titled Wicked Good.

In the back of his mind, there’s also a comedy called Steamed Females, about rival woman-run crab houses. And another on the Cone Sisters, set at their apartment in Bolton Hill. Then maybe one about the father-son Italians who built his back patio, arguing over everything from the house’s shingles to the proper thickness of a slice of mortadella.

“Anyway, I get these ideas,” says Rodricks. “I’ve got a few more stories left in me.”