Fluid Movement celebrates 20 years of community building and radical acceptance.

Arts & Culture

And So Are You

Fluid Movement celebrates 20 years of community building and radical acceptance.

Druid Hill Park Swimming Pool is closed, but at just after 5 p.m. on this sticky late July evening, it’s more crowded than it’s been all day. At one end of the diving pool, a life-size, headless skeleton in a dress slumps into her wheelchair. “I’ve got wire, I’ve got Velcro, and I’ve got duct tape,” a tattooed man with a graying beard offers as a small group of swimsuit-clad women and men brainstorms how best to attach a skull to her spine.

Speakers and tents are carefully carried around another group assembling a massive paper backdrop, while a few young girls chase each other and squeal with excitement over new red costumes by the locker rooms. Sue Thompson’s “Norman” begins to play as the technical producer fiddles with the sound setup, and an enormous fake belly is brought out from the makeshift backstage to evoke the evening’s inspiration—Alfred Hitchcock. The only person not bustling about is the skeleton, whose head is now propped nicely atop her bony neck, a perfect double for Psycho’s dearly departed Mrs. Bates.

Scenes from 2018’s Hitchcock performance.

The dozens of people gathered here to transform the Baltimore pool deck from an aging public space into a functioning theater are members of Fluid Movement, a performance art group that, for the past 20 years, has brought their imaginative shows to communities across the city. For two weekends from July into August, they transform the pools and put on nine shows for crowds packed into the bleachers at Druid Hill and Patterson Parks. Past themes have included Cleopatra and Jeff Goldblum, The War of 1812 and shark-ified Shakespeare, among other things. And their latest creation, “Alfred Hitchcock Presents: The Water Ballet,” premieres in just two days.

Swimmers dressed as birds, police officers, and telephone buttons mill about, looking nothing like what comes to mind when you hear the words “synchronized swimming.” The Fluid Movers come in all shapes and sizes, range from elementary school to retirement age, and few are professional performers. But this is an art form, one that’s been pretty much perfected over the past two decades. Within a half hour, the deck is a bonafide stage. Sound is ready, makeup is done, props are prepared, and rehearsal begins.

This aquatic troupe has become a hometown staple for sparking joy in audiences and drawing together an eclectic crowd of Baltimoreans, but what makes it most special is that it has created a space for creatives of every cloth—countless swimmers, dancers, performers, artists, and everyday citizens who have found a home among the sequins and swim caps of Fluid Movement. This year, their beloved summer water ballet is inspired by their own story, which happens to be an interesting one.

In 1998, it started in, of all places, a book club. After graduating from University of Maryland, Baltimore County as a painting major, Beatrix Burneston, who goes by Trixie Little as a professional cabaret artist, launched a feminist reading group that, among other things, covered how art interacts with communities. But after a while, simply learning wasn’t enough. “We got to the point where we had read a bunch of books and I’m like, ‘Okay, we can sit here and read all day—but what are we going to do about it?’” says Little. She wanted to create something that actually affected how people saw the city’s varied communities and themselves. “Fluid Movement was my attempt to make the world I wanted to live in, and I felt like the most immediate way to connect with people would be through performance.”

From the archives: Heather Crutchfield; Trixie Burneston; Burneston and a fellow devil; Valarie Perez-Schere and Holly Tominack; Chanelle Holloway as Cleopatra.

Inspired by the kaleidoscopic choreography of legendary Hollywood director Busby Berkeley, Little channeled her creative energy into the idea of a water ballet. In her mind’s eye, she could see all different body shapes and sizes, swimming in sync and making something beautiful and fun to bring people together. She just had to find the right team to help make her dream a reality.

One of Little’s first calls was to Megan Hamilton, a founder of Creative Alliance. Hamilton loved the idea but helped Little realize that it was a bigger project than she initially imagined. It would take time to coordinate with pools, gather swimmers, create a show, and spread the word. It was the summer of 1998, and this grand idea needed a chance to develop. So Little started planning for the following year.

At the time, Valarie Perez-Schere was working at Patterson Park Community Development Corporation, where she was in charge of marketing the park and its surrounding neighborhood, which was not yet designated a city arts district and still struggled from lack of investment and positive public perception.

“People still remembered bodies being [found] in the park—the landscaping and all the new stuff, the new pool and dog parks, none of that was there,” says Perez-Schere. “Friends of Patterson Park wasn’t a 501c3 yet. We met in a chiropractor’s office. It was a very grassroots sort of effort. Nancy Supick at Friends of Patterson Park, a saint among humans, said there was this girl who was doing a water ballet in the pool. I said, ‘Shut up! Give me her number!’”

She and Little were a perfect match. Perez-Schere had minored in performance art at University of Southern California. She loved Esther Williams movies and was a lifelong swimmer and devoted city-dweller. A water ballet that could help bring people together in Patterson Park was exactly the kind of project she could get behind.

Together, Little and Perez-Schere brought in artist and choreographer Melissa Martens, another Williams devotee, from the Jewish Museum of Maryland, and they began work on the first-ever Fluid Movement water ballet, “Water Shorts: A Synchronized Swimming Extravaganza.” The performers were friends, coworkers, and neighborhood kids, and they swam in scenes dedicated to the cycle of life—work, play, love, death, rebirth. Many, Little included, had never even taken a dance class. But there they all were, with matching swim caps, sparkles, and clipped noses, sharing something completely new with their community. And somehow, it worked.

People showed up and paid their three dollars to see the show that the Baltimore Sun called “so neighborhood-, family-, and community-oriented, it’s downright populist.” There was homemade lemonade and baked goods for sale poolside, and enthusiastic audiences cheered for their neighbors from the bleachers.

“As soon as it was done, we were like, ‘Let’s do another one!’” says Perez-Schere. With summer over, they decided to move their talents to dry land, and by Halloween, they were roller skating around the park in a performance of Edgar Allan Poe’s “Masque of the Red Death” that featured Death itself, wearing sneakers and trailing red gossamer scarves, rolling up to the Pulaski Monument on a skateboard. “People truly thought we had lost our minds,” says Perez-Schere. “But folks showed up. I don’t remember us charging admission. I don’t remember it even being ticketed.”

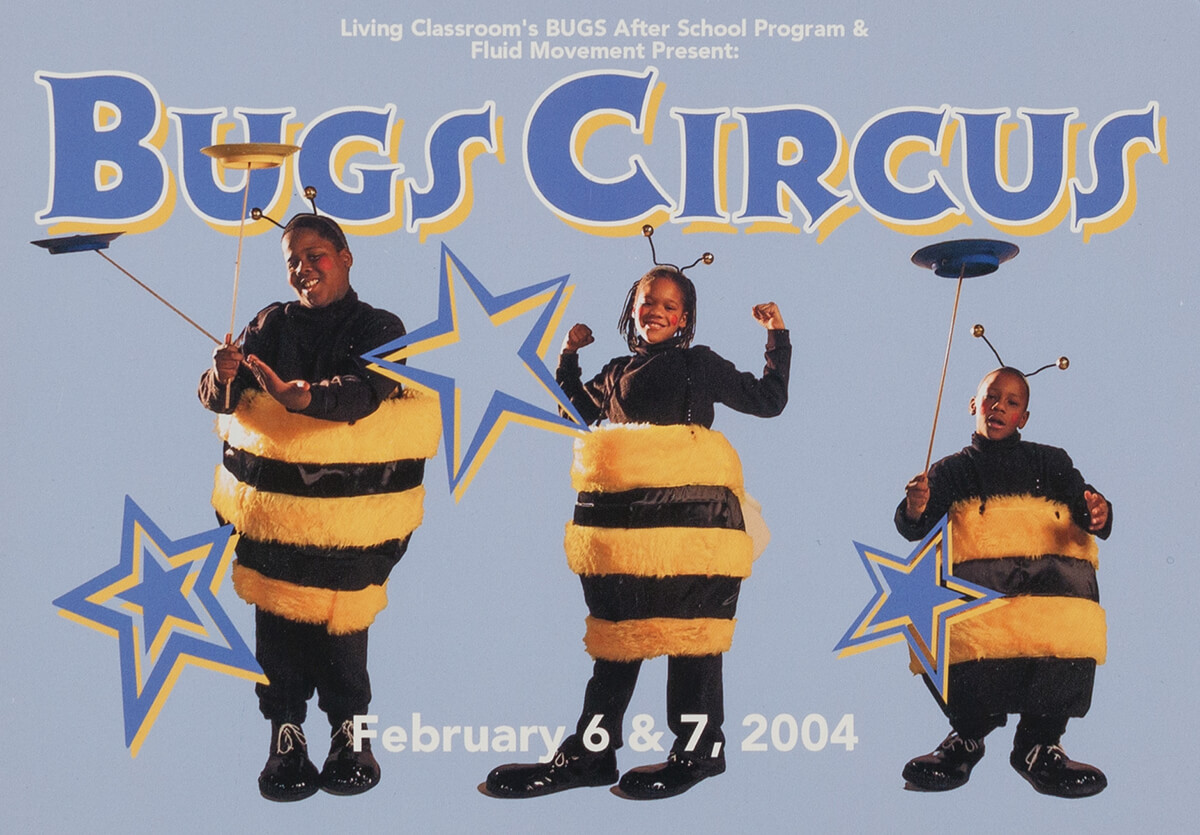

Within a year they’d produced another four shows, and the second Halloween offering, “Frankenstein on Wheels,” drew more than 1,300 people. Audiences were showing up, and with them more people who wanted to be a part of the show. The aim was to create accessible, educational art in urban spaces for any and everyone, and the arts and community development leaders around the city got it. Before long, partnerships with the likes of The Baltimore Office of Promotion & The Arts, HonFest, the Transmodern Festival, and the Living Classrooms Foundation offered opportunities to craft performances of all types, from an adult puppet show based entirely on tchotchkes to a bug-themed circus featuring local school children. Instead of auditions, they held sign-ups. Anyone who wanted to join could find a place for themselves. The founders of Fluid Movement almost never said “no.” Instead, they said, “How can we make it happen?”

Fluid Movement performance posters over the years reflect the eclectic spirit of the troupe.

But that kind of constant creative output can take a toll. After cramming 10 performances into just two years, the all-volunteer team took a three-year break from the water ballets after 2001’s “Cirque de L’Amour.” They focused on other mediums—puppetry, flamenco, and fire dancing among them—while they took some time to cement what Fluid Movement would be in the long term.

Joe Meduza joined the group just before the break. The lifelong performer felt he’d found his tribe in these other passionate and all-embracing artists, and he would go on to perform, direct, produce, and serve as a board member for Fluid Movement. When the group was ready to return to the ballets in 2005—bolstered by incorporation as a 501c3 nonprofit and an Open Society Institute fellowship granted to Little—so was Meduza. He produced his first piece—2008’s “Mother Goosed: The Nurseryland Campaign Tales”—and then one show became three as he tackled “Jason and the Aquanauts: 20,000 Legs Over The Sea” and “Strange Customs: The Flurry Family Odyssey” in 2009 and 2010. “That’s been the highlight for me artistically,” he says. “It’s so open. People have the opportunity to say, ‘Hey, I want to do this,’ and we support them. That’s Fluid Movement. If someone is inspired, there’s something they can do.”

It’s true that most people who have heard of Fluid Movement know them for their summertime spectaculars, but between those sequin-studded events, the group makes a number of other appearances throughout the year. Their dances have long been a fixture at HonFest and Light City, and over the years, Fluid Movers have appeared at Creative Alliance’s Marquee Ball and the Transmodern Festival’s Love Parade in all sorts of themed getups.

Through those partnerships and their growing numbers, Fluid Movement established themselves as an integral part of Baltimore’s creative community. They garnered attention from The Washington Post and NPR, and they even got Baltimore’s own Mike Rowe into a patriotic Speedo as part of his show Somebody’s Gotta Do It on CNN.

And while individual performers come and go, the performances themselves have maintained their DIY spirit and wacky enthusiasm, in many ways akin to Baltimore’s own underdog ethos. Little herself left the group in 2007 to pursue her burlesque career in New York, but she made sure it could outlast her involvement through her Open Society Grant and has since watched it thrive from afar under the leadership of Perez-Schere, the boards, and dedicated volunteers.

“I see Fluid Movement as a really important cultural institution for the city,” says Little. “It’s a bit of an unsung hero because it’s all volunteer. But to me, it’s up there with the American Visionary Art Museum and Creative Alliance and these other big institutions because of what it does. It really builds community. What it does to make people feel good and connect with Baltimore and do something greater than themselves is priceless.”

Some Fluid Movers, like Ashley Ball, came into the fold never even expecting to get in the pool. Her first encounter with the group came in 2014, when she saw a poster for “Star-Spangled Swimmers,” Fluid Movement’s War of 1812-themed water ballet. She watched a group dressed as Dolly Parton Madisons—a mashup of the First Lady and the Queen of Country—saving art from the White House, and she was hooked. “It was everything,” says Ball. “I was so into it. I thought, ‘This is something I have to be a part of.’” There was just one hitch, she didn’t really swim.

But, after finishing her graduate degree at Johns Hopkins University, Ball found herself unemployed and performing with the Baltimore Rock Opera Society (BROS), another outsider performance art troupe located in the city.

“I met Margaret Hart, who’s a Fluid Mover, when we were making garbage for a trash-themed party at BROS. She was making this giant tampon—it was huge—and I was like, ‘I like you, I love that this is where your head’s at. We can be friends.’ She told me about a dance show that Fluid Movement was doing for Light City that year, and love just bloomed.”

Since that first foray into Fluid Movement, Ball has danced and acted at countless events, crafted all kinds of props, created choreography, and, this past summer, finally jumped into the pool. In February, it all came back to trash as she directed a performance to introduce the documentary Trash Dance. Two dozen Fluid Movers dressed as sanitation workers, rats, and raccoons spun their way around Bond Street's Brown Advisory carrying brooms and oversized cutouts of city garbage while a mix of Lionel Richie, AC/DC, and Outkast played over the loudspeakers. The audience giggled, clapped, and cheered them on. And over the applause, Fluid Movement yelled their signature ending slogan: “We are Fluid Movement, and so are you!”

That “and so are you” is at the heart of everything. When Fluid Movers talk about this strange, wonderful collective they’ve created, it’s always with such joy: “I found my tribe.” “Love just bloomed.” “It’s just an amazing group of people.” “We share so much.” Each one saw a dance or water ballet or roller show, worked up the courage to sign up for something, and was immediately embraced by the Fluid Movers. They stick like glitter to those they touch.

Some, like Will Archer and Suzy Kopf, even got hooked on each other. The pair met at a Fluid Movement rehearsal in 2015 and have been swimming together ever since. Last August, as the cast of “Alfred Hitchcock Presents: The Water Ballet” danced on the spotlit deck of the Patterson Park pool in front of a packed house to close the show, Will got down on one knee while some conspiring audience members produced signs that read, “Suzy, Will You Marry Me?” Suzy, much to the crowd’s delight, said yes.

“I’m a big fan of cyclical things,” says Archer. “We met doing water ballet . . . It just made sense.”

“And who can say they’ve been proposed to on stage in a swimsuit?” adds Kopf with a laugh. “Not many!”

Joe Meduza, left, and Amelia Meman in costume at Fluid Movement HQ.

Those who aren’t actual couples connect in other ways. The Fluid Movement Community Facebook group of more than a thousand members stays active with invitations to events, inside jokes, and posts about all things water ballet. There are weekly “Skills and Drills” swims at pools across the city and movie night screenings of past performances to gather at throughout the year.

That ability to bring people together is by design. Fluid Movement’s mission was, and still is, to be a place that’s welcoming to all. At a time when self-love and body positivity weren’t yet buzzwords, Fluid Movement offered radical acceptance in a space that didn’t just allow all kinds of bodies, but also celebrated them.

“Seeing these people bare their bodies is a whole other piece of why this is so important for people and why it’s important to me,” says Perez-Schere. “Seeing trans people in bathing suits and having people in drag in bathing suits, not just in a performance, but in public in a city pool, was some transgressive shit 15 years ago. . . . Those are the ephemeral little pieces of bringing a community together that are vital.”

Fluid Mover Amelia Meman, who works as the program coordinator for University of Maryland, Baltimore County’s Women’s Center, was drawn to the group’s inclusivity and sees the water ballets as a testament to what her body can do. She deals with a chronic illness, and through Fluid Movement she found a space to both succeed and fail around people who encourage her. “You can be somebody who’s still learning, and that’s fine,” she says. “We share something so unique and strange and weird, and there’s an amount of beauty and love in it that’s just contagious. It takes a lot of work, commitment, an creative energy, but it’s such an empowering process that it’s hard not to want to do it again.”

After 20 years as an essential part of Baltimore’s creative landscape, Fluid Movement is still working to improve and share those moments with everyone they can. It has already become a place of acceptance and fulfillment for so many, and Meman hopes that it can continue to reach into even more communities. “There’s a really desperate need for more racial diversity,” she says. “I know that there are folks who are involved who are differently abled, and we tend to check off the box in terms of gender expression and sexuality. But I am really eager to involve more people in the work that we do, especially folks who look different from me and look different from a lot of the folks who are involved. It’s a place where we can make space for anybody and, hopefully, everybody.”

That reaching out can start with the inclusion of local kids, which Baltimore City Recreation and Parks aquatics coordinator Nikki Cobbs sees as some of Fluid Movement’s most valuable work. “I believe that Fluid Movement, in doing their practices at the pools, shows inner city kids a different way of thinking,” she says. “Some of them knew nothing about water ballets until Fluid Movement came. [The group] tries to help us change the culture at the pools. If the kids want to be in the show, they try to find a way. It really shows our kids something different than what they’re used to.” Nearly every water ballet has included children, and the welcome also extends to the local lifeguards, several of whom have acted in the ballets and shown off their diving acrobatics as part of the show. Anyone and everyone is welcome.

It’s a radical concept: A performance-based group with no audition process or experience or skill requirements. Just people who want to do something together making it happen, one crazy idea at a time. The fact that those crazy ideas seem to work, over and over again, after 20 years of dancing, skating, and swimming, is worth celebrating.

And so this July and August, the theme will be Fluid Movement itself, a magic-laced look behind the scenes at what goes into a water ballet: the “technical excellence, raucous joy, somber beauty, Hollywood glamour, and just plain weird,” as they put it. Ghosts of ballets past will work their ways in, but the 20th anniversary show is also an entrance into a new era.

“Fluid Movement: The Water Ballet,” a self-titled album of sorts, will be the final show at Druid Hill Park Pool for now, before it closes this fall for a multi-year renovation.

Perez-Schere is co-directing Ball’s water ballet directorial debut this year, and her daughter Lilly and her best friend Emilia, both longtime Fluid Movement kid swimmers, are directing their first-ever scene together. A new Fluid Movement president will likely be elected in October, though Perez-Schere plans to stay on as artistic director. The change will help balance the workload and allow for more voices to be involved with the organization’s direction. The following month, Fluid Movers past and present and their supporters will celebrate their shared history with a gala at AVAM, a glittery class reunion for those who’ve had the unique experience of creating artistic spectacles in front of the city they love, and finding a new sense of belonging in the process.

“One of the beautiful parts about being in the shows is starting to feel a sort of belonging to a place,” says Perez-Schere. “Occupying a space for a long time changes it for you. If you feel disconnected from Baltimore, if you’re new to town, if you’ve just broken up with somebody, if you need a change in your life, if you just want to play more, if you think this might be something for you, come to sign-ups. With the people that you meet and the vibe that you get, you’re going to want to do it.”

It’s like they always say: They’re Fluid Movement, and so are you, if you’d like to be.