The fast times, hard luck, and rebirth of bluegrass in Baltimore.

Arts & Culture

True Blue

The fast times, hard luck, and rebirth of bluegrass in Baltimore.

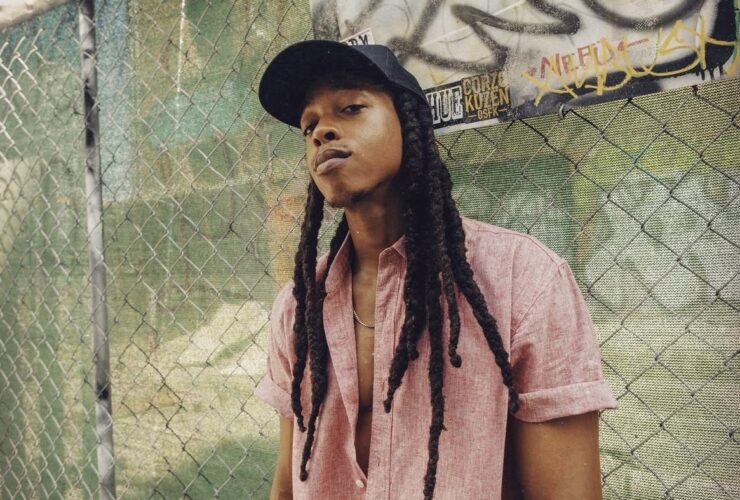

Opening image: Earl Taylor and the Stoney Mountain Boys perform at the 79 club IN Baltimore, late 1950s. Getty Images

Backstage, behind the thick, dark curtain, they heard the hum come on slowly. “Like a bee swarm,” recalled banjo player Walt Hensley. It was a Friday night in early April, 1959, and hundreds, if not thousands, of urbanites had gathered here, in the heart of New York City, to hear these country musicians play.

Decked in cowboy hats and string bow ties, the Stoney Mountain Boys were not used to such sophisticated audiences or grand and gilded venues. After all, they were from a small industrial city south of the Mason-Dixon, some 200 miles away. But they’d been invited here at the behest of famed folklorist Alan Lomax, who wanted to show the world a “panorama of the contemporary American folk song revival,” with the evening’s concert also including gospel singers and blues acts, like Muddy Waters and Memphis Slim.

Looking out over the giant room, the band stood wide-eyed in wonder at the bright golden lights and the four tiers of balconies filled with red velvet seats. “It began to take effect,” said Hensley. “This wasn’t the kind of hall I was used to playing . . . ”

Banjo made in Baltimore in 1845.

National Museum of American History

But after calming their nerves with whiskey, the band took to the stage—frontman Earl Taylor on mic and mandolin, Hensley on banjo, Sam “Porky” Hutchins on guitar, Vernon “Boatwhistle” McIntyre on bass, plus Curtis Cody on guest fiddle—and though they were greeted with little applause, Taylor flashed a smile at his fellow musicians and launched into the fastest song they knew.

This rip-roaring number, aptly named “Fire on the Mountain,” was unlike anything these city slickers had ever heard—a high-speed, hard-driving string sound that exploded off the stage and across the audience like the winds of a locomotive. And when the final chords hit and the room fell quiet, the crowd erupted in cheers, “rarin’ and screamin’ and hair-pullin’,” as Taylor later recalled.

This unexpected music had been born in the rural South—a young American genre fueled by little more than a few strings and fast-flying fingers. But it would be these Stoney Mountain Boys, a bunch of blue-collar musicians not from Louisville or Lexington or even Nashville, but the streets of Baltimore, who would be the first band to perform it at Carnegie Hall, lighting a spark that would inspire musicians for generations to come.

“They were the first bluegrass band to play Carnegie Hall, and I knew those guys,” says bluegrass veteran Del McCoury, who spent his early days in Baltimore. “They had it, they really did. They made a big splash in that part of the country, man, and a lot of musicians sprang out of listening to them . . . But you know, they never got out of the clubs. They were just one of those bands that never did . . . ”

Bluegrass was born in rural Kentucky, stemming out of the simple mountain music from the blue-tinged hills and backwoods of the Appalachian Mountains. It was brought to prominence by Bill Monroe, “the father of bluegrass music,” and his band, the Blue Grass Boys, from which the genre takes its name. In the 1940s, with the radical picking of now-legendary banjo player Earl Scruggs and guitar player Lester Flatt, they gave country music a modern shot in the arm, ratcheting up the old hillbilly sound into tight, up-tempo tunes defined by their “hard driving” and “high and lonesome” nature.

Bluegrass would be bred, however, farther north, in cities like Cincinnati, Detroit, Pittsburgh, and even Baltimore. The Great Depression had struck a serious blow to the already beleaguered economies of Appalachia, and over the years that followed, much of its rural population would migrate to these industrial epicenters to find work. The New Deal and World War II would create a boom for manufacturing jobs, especially around the Baltimore harbor, where the port lured laborers, longshoremen, and factory workers to the likes of Bethlehem Steel, General Motors, and the Martin Bomber Plant. By the 1950s, Baltimore was the sixth-largest city in America and a bona fide working-class town, built on thriving industries and an influx of both immigrants and migrants.

Curtis cody, earl taylor, Walt Hensley, sam Hutchins, and Vernon Mcintyre LIVE AT CARNEGIE HALL, 1959. Ray Sullivan

But besides their labor, these new rural residents were not welcomed with open arms. “No Dogs or Hillbillies” read For Rent signs of the day, which led many families to isolate themselves in like-minded pockets of the city, packing into rowhomes in Hampden, Highlandtown, Charles Village, Dundalk, and Middle River, which would come to be known as hillbilly ghettos. To foster a sense of community, these newcomers, most of whom were descendants of English, Irish, and Scottish settlers, turned to one of the few things they were able to carry with them from the mountains—their music—and before long, late-night picking parties cropped up in living rooms and kitchens on weekends. These impromptu concerts acted as common ground, with familiar jigs and ballads performed with a medley of string instruments. The fiddle played a starring role, while mandolin, guitar, and banjo filled out the lineup. (The banjo actually has deep Maryland roots, having been brought to America by enslaved Africans, many of whom landed along the Chesapeake. Later, the first commercial banjo was built in Baltimore in the 1840s.)

By the mid-1950s, house parties, more bohemian than blue-collar, had started to pop up in more affluent neighborhoods, too. In the homes of arts patrons, rural migrants mingled and made music with urban hippies and college-educated folkies. “We’d go in at 8 o’clock at night and come out 8 o’clock in the morning,” recalls Russ Hooper, a regular at these gatherings and a Dobro player in one of the city’s earliest working bluegrass bands, the Pike County Boys (whose frontman, Bob Baker, often threw such jam sessions himself). “I can remember going to brownstones up on St. Paul or Charles or Calvert Street with the likes of Mike Seeger,” he says.

RUSS HOOPER, age 15, 1951. Russ Hooper

In many ways, it was Seeger who changed the bluegrass game when he arrived in Baltimore for work in 1954. In addition to hailing from a rich musical family—his half-brother was legendary folk singer Pete Seeger, his parents were both American folk music experts, and they were all friends with Alan Lomax—Seeger would lug around a 40-pound reel-to-reel tape recorder to local performances. These recordings would help promote Baltimore artists outside city limits—Earl Taylor, Bob Baker, Hazel Dickens, who would become a trailblazer for female bluegrass musicians and early feminist songwriters. In fact, they would help land the Stoney Mountain Boys that starstruck moment at Carnegie Hall.

“Baltimore kind of lucked out that Seeger was here recording,” says Tim Newby, author of Bluegrass in Baltimore: The Hard Drivin’ Sound and Its Legacy. “It made a big impact. He had some famous connections that helped these guys get exposed to a wider audience.”

At the same time, the Appalachian picks and beatnik house parties had poured over into the local bars and clubs. There were dozens of what we would now call dives, speckled all across the city—the 79 Club in Federal Hill, the Blue Jay and Jazz City in Fells Point, the Chapel Café near East Baltimore, the Franklin Town Inn in West Baltimore, the Stonewall Inn and Cub Hill Inn north of the city—where some seven nights a week, that rhythmic music would burst out of these small, seedy watering holes as a growing brood of bluegrass musicians cranked away on the pint-sized stages.

“It was old-time music in overdrive, I tell ya,” says McCoury, who cut his teeth in some of these beer-slick, smoke-filled bars. “It really had something that would hit you hard, and lots of people said it was too strong for them! At that time, on the radio, you were hearing Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra—that’s crooning music, and it’s really good. But it’s a lot different than bluegrass.”

Many musicians were playing every night, with an extra matinee on Sundays, on top of their full-time jobs. “They were long days,” says Hooper, who worked at Western Electric. “You’d play from 9 at night until 2 o’clock in the morning, just to get up at 6:30 and go back to work again. And back then, you were only making $5 or $6 a night.”

MARVIN HOWELL AND THE FRANKLIN COUNTY BOYS, 1963. DIANA DAVIES/RALPH RINZLER FOLKLIFE ARCHIVES

That hustle came out in much of the music, with most songs longing for the simpler days of country living or lamenting the hard luck of city life. And in these bars, known for their rough reputations and rowdy patrons, the crowds could relate. Fights were a common occurrence as the liquor flowed and the band only grew louder and faster as the hours wore on. “But we kept playing!” says McCoury with a chuckle. “Not the kind of places you’d take your wife with you.”

But it was in these bars that some of the most influential bluegrass musicians would master their craft. There was Earl Taylor and those Stoney Mountain Boys, who would go on to cut a record with Lomax following their Carnegie gig. Bob Baker and the Pike County Boys with Hooper, who, like many musicians, shuffled between different bands. Marvin Howell and the Franklin County Boys, which at one point included McCoury, who would eventually be scooped up by the one and only Bill Monroe after a set at the Chapel Café in 1963. “Baltimore was a great training ground,” he says today. “After the evening got along and people got drinking, you realized you could do whatever you wanted to, because the crowd would enjoy just about anything. You could improvise and try new things and get your confidence up.”

And that they did. “If you’re surrounded by great musicians—and these were some tough clubs with some great pickers—you’re going to bring your A game,” says Paul Schiminger, executive director of the International Bluegrass Music Association.

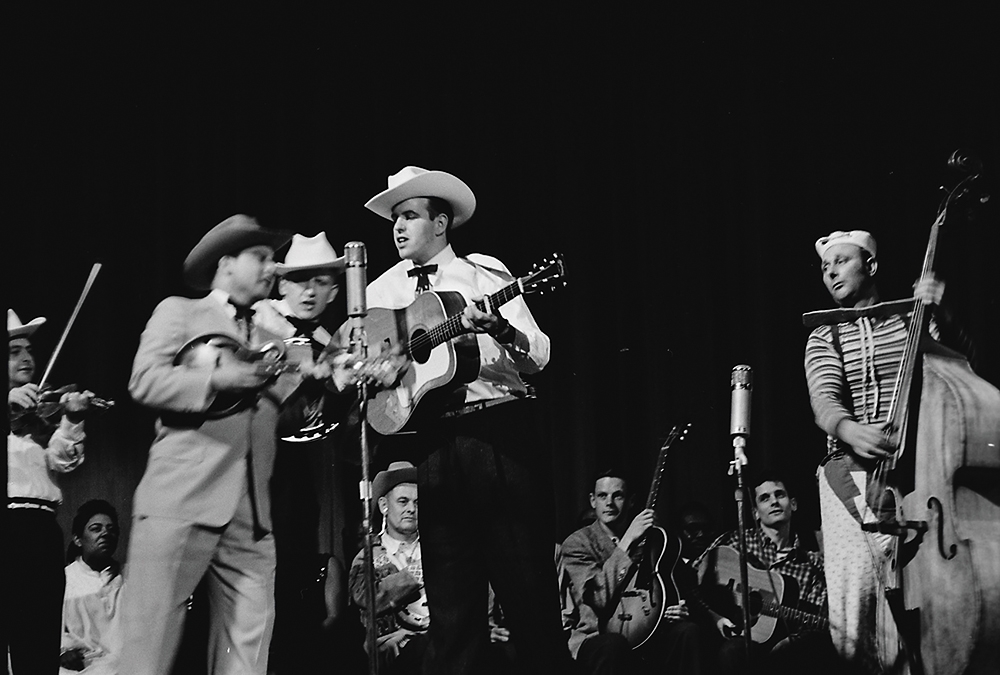

A young boy watches as LESTER FLATT AND EARL SCRUGGS rehearse backstage at Sunset Park, 1961.

John Cohen/Getty Images

John Cohen/Getty Images

Big-name acts would pass through Baltimore, too, on their way to the country music parks northeast of the city. Every Sunday, a stream of cars would file up and down Route 1 for a full day of entertainment at only $1 admission. In Rising Sun, Grand Ole Opry stars such as Monroe and his former bandmates Flatt and Scruggs headlined the New River Ranch, drawn in part by the event’s emcee, local radio celebrity Ray Davis, as well as the Campbell-Reed family proprietors, who were hillbilly music royalty, with matriarch Ola Belle Reed revered as a mother of bluegrass. The ranch was destroyed by a blizzard in ’58, but just over the Pennsylvania line, Sunset Park would live on until 1995 and host the likes of Hank Williams, Johnny Cash, and Dolly Parton.

But despite the trove of talent, in Baltimore and beyond, bluegrass remained somewhat of a niche genre, much as it has today. McCoury recalls early competition from rock ’n’ roll, with his schoolmates discovering Elvis Presley when he first found Flatt and Scruggs. And the hillbilly stigma remained hard to shake, as “the term ‘bluegrass’ often brings to mind this bad, preconceived notion of uneducated mountain men,” driving away potential listeners, says Newby.

“Bluegrass has always had its peaks and valleys,” explains Hooper, and that was certainly true in Baltimore, with the city’s scene never quite taking flight beyond state lines. Some musicians flirted with the edge of stardom, but most lacked managers or booking agents to help steer their business decisions. The Stoney Mountain Boys, for instance, found varying levels of fame but never quite capitalized on that Carnegie moment, ultimately ending up back in the Baltimore clubs before relocating to Cincinnati in the early ’60s.

Others simply passed up opportunities to find success on their own terms, be it for pride or blue-collar pluck. Ola Belle Reed was courted by “King of Country Music” Roy Acuff for a spot in his band, which she famously refused: “I wasn’t taking orders from no man.” And Russ Hooper unapologetically turned down a golden ticket from Flatt and Scruggs to keep his steady paycheck.

“There’s an old saying: don’t give up your day job. And I learned that a long time ago,” says Hooper. “At the time, I had a good job, and I knew if I hung in long enough, it would provide a good retirement, which it did. Besides, I knew how music was back in those days . . . ”

Another blow landed by the 1970s, when just 40 miles south down the beltway, a burgeoning scene would take advantage of the genre’s full potential. Washington, D.C., had started to gain notoriety for two new groups, the Country Gentlemen and the Seldom Scene, both willing to push the envelope further than their small-town neighbors, who were far more bound to tradition. With bigger, better venues frequented by a more attentive, upscale crowd, the district would soon be knighted “the capital of bluegrass.”

It’s ironic, because not only was Baltimore a pivotal part of bluegrass’ past, it also played a role in establishing its future. Though largely lost to history, Walt Hensley of the Stoney Mountain Boys enacted a sort of sea change with his 1969 solo record, Pickin On New Grass. In the age of experimentation, these inventive songs and the idea of a modern take on the old genre would inspire a new generation of musicians who, with less direct ties, if any, to Appalachia, could better relate to the emerging style. (One notable example is none other than Jerry Garcia, who infused sounds he heard in the Mid-Atlantic into his original jam band, The Grateful Dead, and later, his own bluegrass outfit, Old & In The Way.)

OLA BELLE REED, 1978. Ola Belle Reed

In Baltimore, this next wave would find a home around the cast-iron woodstove of Baltimore Bluegrass, a beloved music shop on Belair Road that, from 1975 until it closed in 2000, hosted weekly jam sessions and helped revitalize the local scene. It would be a place of refuge for both professional musicians, like revered picker Mike Munford, and amateurs, like a teenage Cris Jacobs, who took his first and only banjo lesson at the store. That one taste would prove to be enough for Jacobs, who formed his own bluegrass group, Smooth Kentucky, in 2003. The band would help launch the city’s roots music revival of the early aughts, as well as the careers of Jacobs, a rising solo artist, and bandmate Patrick McAvinue, who was named the IBMA’s Fiddler of the Year in 2017 and now performs regularly at the Opry.

“In many ways, it’s a natural evolution,” says Newby. “There’s this perception of bluegrass being this really old music, and its roots are old, like jazz or blues or rock ’n’ roll. But the term wasn’t even used until the late 1950s, and it’s easy to forget that these guys were trying to get away from some of that old country sound. They were experimenting, and the young guys are now keeping the scene alive in their own modern way.”

Today, Baltimore’s bluegrass heyday is something of a distant memory—the dives are long gone, as are many of the jobs around the harbor. But if you listen hard enough, and know where to look, you can still hear a hint of the sound that was born in the Appalachian Mountains and bred along city streets.

One of the last true haunts might be Jumbo Jimmy’s, a roadside crab shack in Port Deposit where bluegrass still incites a floorboard stomp every weekend in Cecil County. And nearby, in Elkton, Ola Belle’s nephews Hugh and Zane Campbell keep the legacy alive out of their old country store. In the city, every other Tuesday, musicians now gather in the back corner of the Five & Dime Ale House in Hampden for a traditional jam session, much like those of the hillbilly homes and brownstones more than half a century ago. And every third Thursday, local and national pickers perform at The 8x10 in Federal Hill, across the street from where the old 79 Club once stood, where Alan Lomax first saw the Stoney Mountain Boys. One night there this past winter, up-and-coming Baltimore bluegrass band The High & Wides shared the stage with the Seldom Scene, that savvy D.C. band from the 1970s.

“On some level, these guys become peers,” says Newby. “It creates a continuous scene and allows the younger musicians to feel like they’re a part of something—the next link in the chain.”

That link has been forged in large part thanks to another local venue: the rolling hills of Druid Hill Park. Now in its seventh year, the Charm City Bluegrass Festival has created new common ground for bluegrass musicians of every era, bringing together both old-timers, like Pennsylvania supergroup Bluestone (featuring Russ Hooper), and newcomers, such as The Dirty Grass Players and Charm City Junction (with McAvinue on fiddle).

Last year, Del’s sons—The Travelin’ McCourys—returned to their father’s stomping grounds and headlined Friday night of the festival. As the warm spring air whistled through the trees, they invited a half-dozen local legends on stage with them and launched into a hearty cover of “Why Did You Wander?” by Bill Monroe. “We played 30 minutes of traditional bluegrass, the way it used to be, here in Baltimore,” says Hooper, who was there that night and remains one of the region’s revered session players. “I’ve been doing this almost 70 years now, and I tell you what, it’s been fun.”

Despite its name, the two-day festival also draws from the broader umbrella of Americana, like local acoustic revivalists Caleb Stine, Letitia VanSant, and Ken and Brad Kolodner.

“All music is related,” says McCoury, who launched his own DelFest in Cumberland in 2008. “In my earlier years, I didn’t think that. I thought there’d be nobody like Earl Scruggs or Bill Monroe, which there wasn’t! But as I got older, I started to think, well, they had to listen to somebody who came before them . . . There’s a lot of good music coming from all directions, if you just listen.”

On the last Saturday of April, Cris Jacobs will return and wrap up the festivities with his jam band, The Bridge, which draws inspiration from bluegrass and the Grateful Dead. And when those hometown boys step onstage, it could be said that it was all set in motion by another band from Baltimore, who 60 years ago this month, as the bright lights rose and the room fell quiet, made music history.

“So many people don’t realize how much bluegrass was a part of this city’s fabric,” says Schiminger of the IBMA. “And how much Baltimore was a part of bluegrass’, too.”