Business & Development

How Architect George Kostritsky Revitalized Downtown Baltimore

Co-founder of groundbreaking firm RTKL died of COVID-19 complications in July, shortly after his 98th birthday.

“It’s like that movie Big Fish, you can’t believe all this happened in the life of a single person,” says Tom Gamper of SM+P Architects. “But with George, it did.”

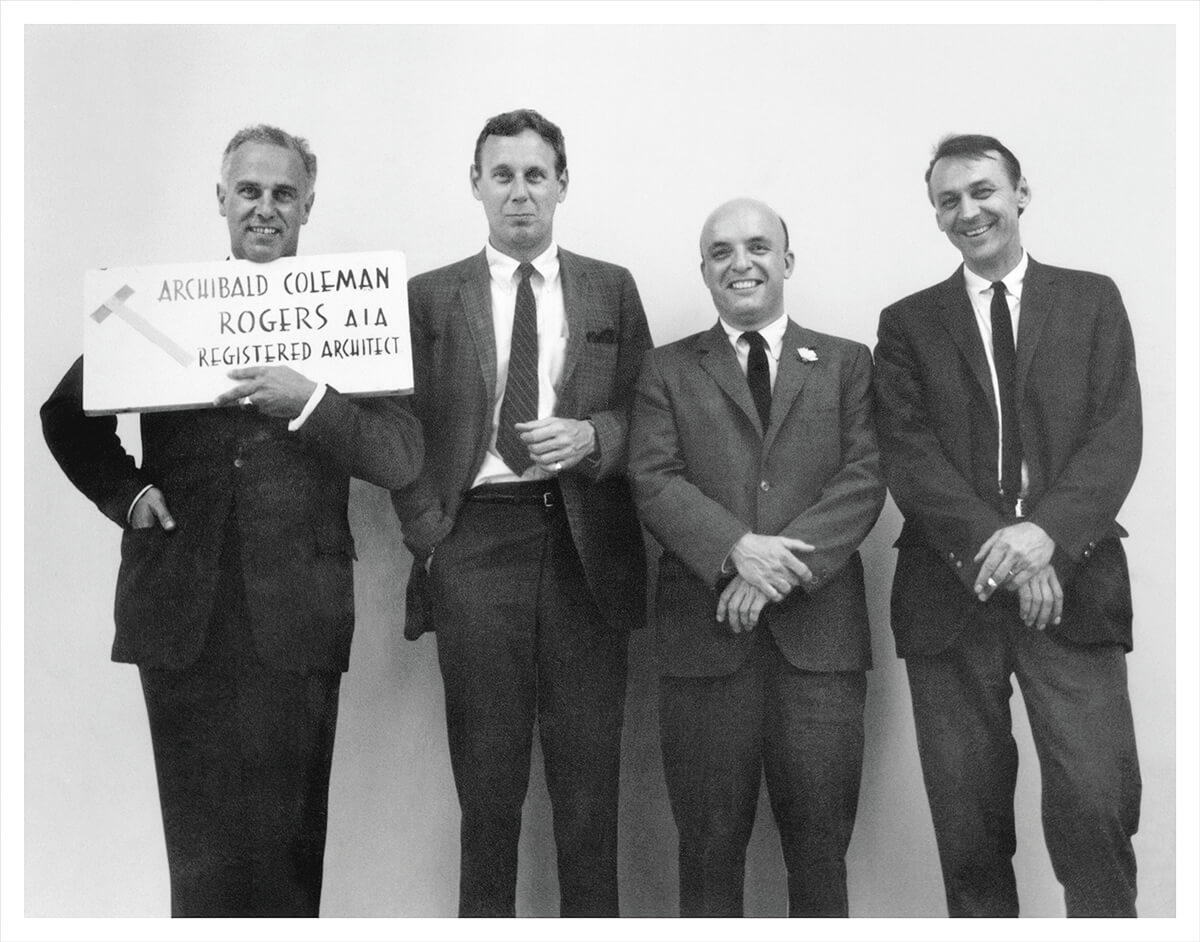

Pictured at far right with Archibald Rogers, Francis Taliaferro, and Charles Lamb, founders of the groundbreaking architecture firm RTKL, George Kostritsky died of COVID-19 complications in July, shortly after his 98th birthday. A gifted urban planner, the last of the original RTKL partners (now the global firm CallisonRTKL), Kostritsky left an impact on cities across the country, most notably his beloved adopted hometown.

At the behest of the Greater Baltimore Committee, he arrived in 1957 to help with nascent plans to revitalize downtown, which was already suffering the consequences of suburban flight. A big-picture thinker, Kostritsky soon became the lead planner of the pioneering 33-acre Charles Center project, which eventually included the rehabilitation or construction of a dozen buildings and series of plazas and interconnected stairways that remain a modernist landmark.

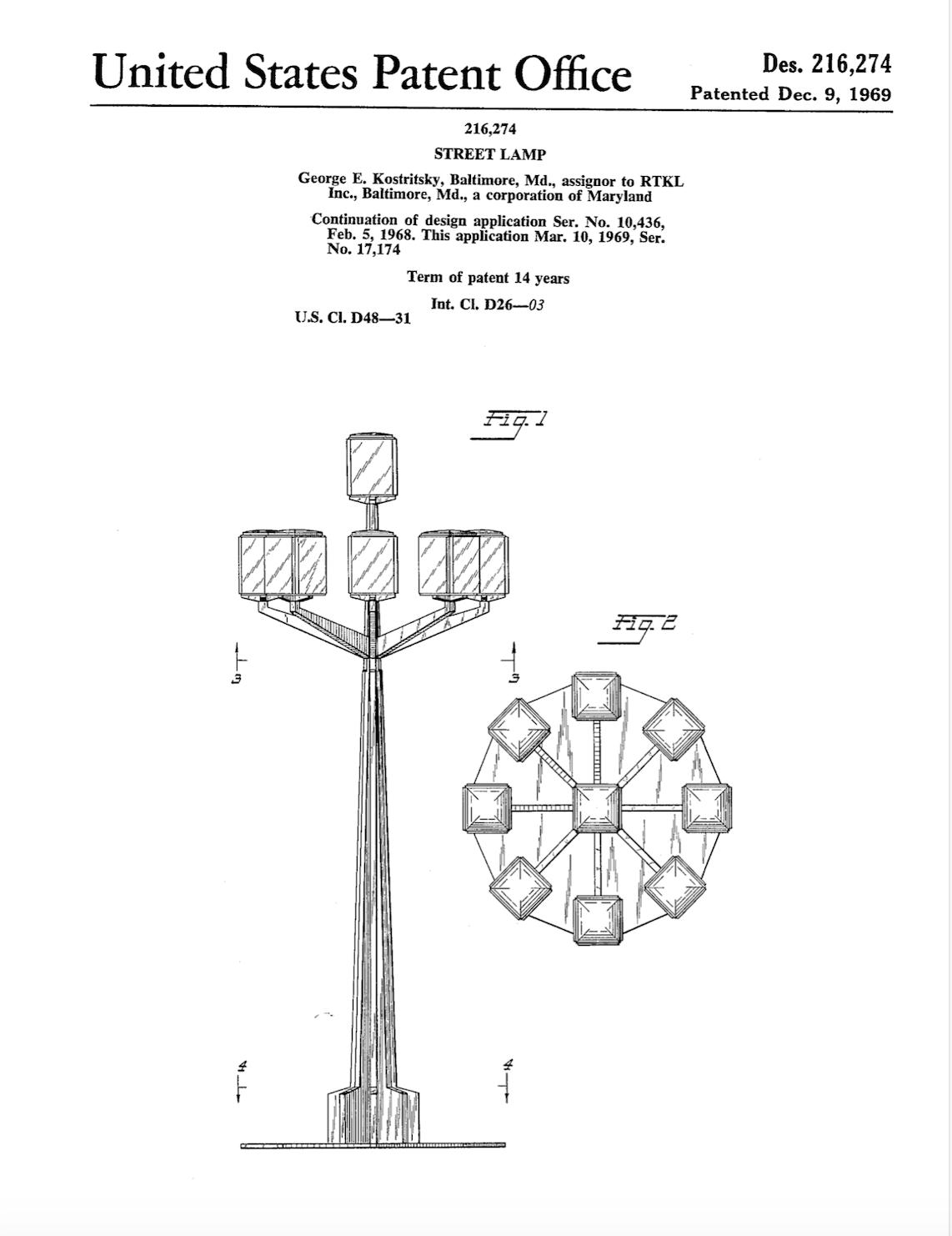

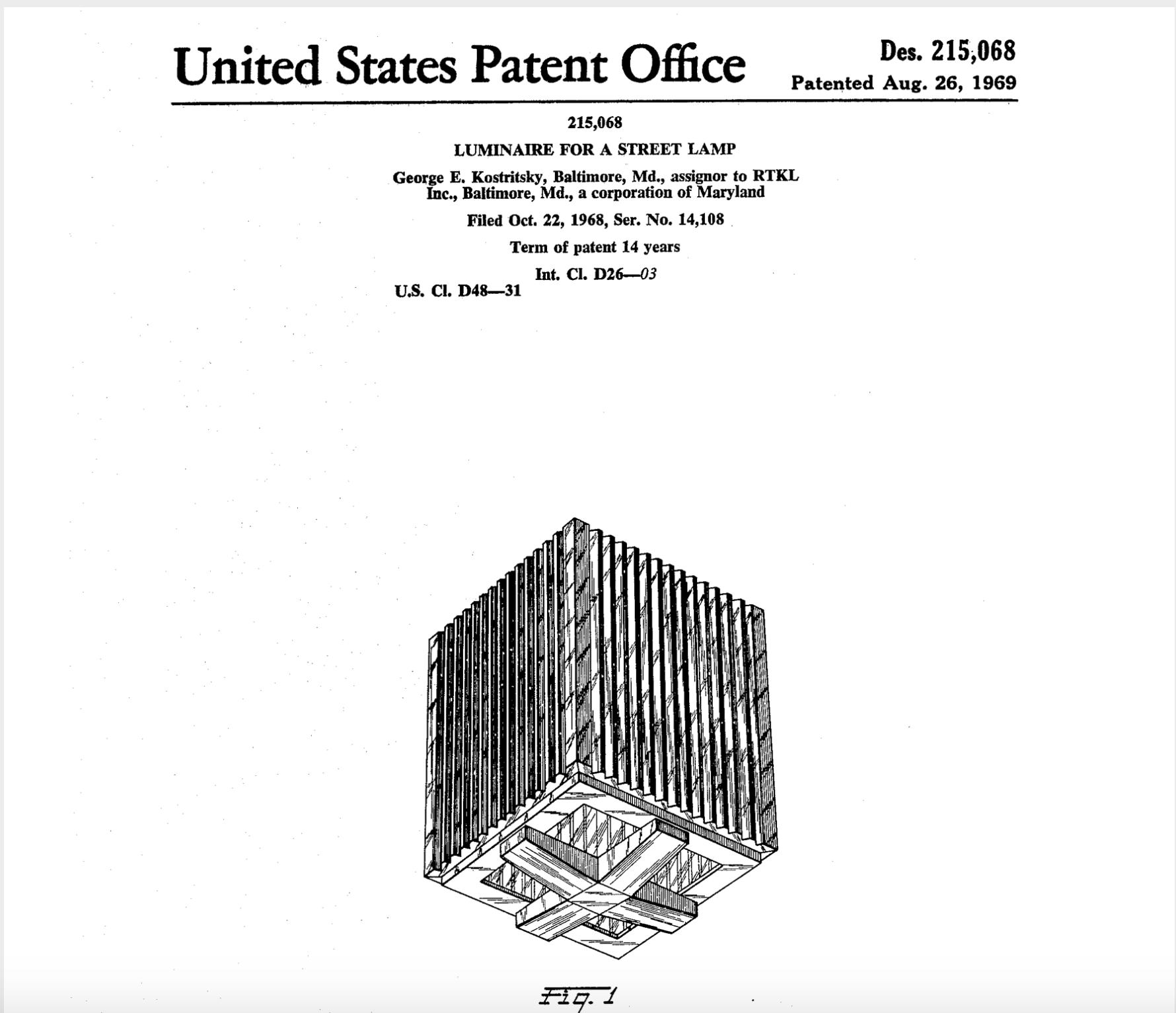

In the process, Kostritsky created and obtained U.S. patents for the unique sugar cube-shaped streetlamps that brighten Charles Center’s public spaces to this day. None other than acclaimed urbanist, activist, and author Jane Jacobs, who penned The Life and Death of Great American Cities, visited Baltimore and praised the early example of adaptive re-use “in the very heart of downtown . . . for precisely the things that belong in the heart of downtown.”

“George was part of that era of ‘heroic’ architects and planners who came out of the ’40s and ’50s, when Baltimore was still crammed with slums and homes that didn’t have indoor plumbing, and had the vision and confidence great things could be done,” says Gamper, a longtime friend. “People like Jim Rouse, David Wallace, Martin Millspaugh, and George believed in cities. And they believed in placemaking. I think that’s why the modernist buildings of the period still resonate.”

Born in Shanghai to Russian immigrant parents who fled the Bolsheviks across Siberia by train and foot—his father had been a World War I pilot in the Tsar’s army—Kostritsky later grew up in San Francisco. Fluent in Russian, he joined the U.S. Navy during World War II and served as an interpreter for a clandestine partnership between FDR and Stalin, known as Project Zebra, which secretly trained some 300 Soviet aviators on U.S. soil for the bombing of German submarines.

After the war, Kostritsky earned a degree in architecture from the University of California at Berkeley. His master’s thesis at MIT focused on designing urban areas to meet social needs.

With the addition of Kostritsky, RTKL began applying its local experience to urban projects in such places as Albany, New York; Charlotte, North Carolina; and Cincinnati, where the Kostritsky-designed Fountain Square remains the hub of that city’s restaurant district. In the late 1970s, he left RTKL for the U.N., and projects in Sri Lanka and Nigeria. He also taught at Harvard and Howard universities before retiring in 1995.

After the death of his wife, Penny, in 1991, Kostritsky met Sheila Hoffman, an art teacher and potter, at an Engineer’s Club luncheon. Eventually, they would share a home in Bolton Hill.

“We had a lot common,” Hoffman recalls. “He’d gone to Berkeley, and I’d gone to UCLA. We both loved the Bauhaus. He called the next morning and said he thought we should take a trip. I asked where and he said, ‘I have Paris in mind, but let’s go to the Eastern Shore.’”

Two years ago, Kostritsky moved into an assisted-living facility as his mobility declined. Sadly, due to COVID-19 precautions, Hoffman and family had not been able to visit for months, even once it became clear that he was gravely ill. In addition to Hoffman, Kostritsky is survived by his son, Gyorgy, and daughter, Juliette, a law professor. A memorial get-together remains on hold for now.

“Dad lives in all of us, his children and grandson, because of his love of art and architecture,” Juliette Kostritsky says. “He took us to art museums, and on Sundays, we’d go for drives to look at buildings under construction. It’s what we did. He was always sketching and later made watercolor paintings. It’s no surprise my brother is an artist and I married an architect. Or that his grandson teaches in Paris and is an artist. It’s funny, too, I keep learning more about my father since he died. I hadn’t known he’d earned a patent for the Charles Center streetlights. When this is all over, I want to visit some other cities and see more of the places and buildings he designed. That would make a great post-pandemic road trip.”