Community

The greater metro region is one of the wealthiest anywhere. Here are some bold ideas to break down the city's barriers.

he march of floats, fire trucks, and drum and bugle corps drew some 30,000 spectators to stoops and sidewalks from Falls Road to Keswick Road. Lottie Carnell, just 17, was named “queen” of the massive parade, and the teenager and her court led a nearly two-hour romp through Hampden’s balloon-filled “jubilant streets,” according to press accounts. Afterward, there was public dancing late into the night on the closed-off streets of Elm and Hickory, just off The Avenue.

The twilight fete, including a bonfire, in the summer of 1948, capped off three days of celebration. Not to commemorate the end of a war, the community’s founding, or even an Orioles championship—the O’s were still a minor league club then—but, wait for it, the 60th anniversary of Hampden and Woodberry’s annexation from Baltimore County into Baltimore City. Hooray, indeed. Who could imagine Charm City today without those neighborhoods’ vital commercial districts, repurposed mills, and quirky “Hey, hon” vibe?

Less than five months later, an overlooked referendum—written by a Baltimore County politician at the behest of the local Democratic party machine—ensured there would be no more Hampdens and Woodberrys annexed into the City of Baltimore. Or for that matter, any other Highlandtowns, Lauravilles, Violetvilles, Ashburtons, Howard Parks, or Roland Parks. All those neighborhoods, among others, had been annexed from Baltimore County and into Baltimore City (along with roughly 50 square miles of Anne Arundel and Baltimore counties) decades before the Hampden-Woodberry-Baltimore City lovefest.

The change to the state constitution may have appeared innocuous. It merely required that a majority of residents living within the annexation area approve annexation. In fact, it was not. There had been a decade-long fight prior to the massive 1918 annexation, which, like previous annexations, enabled Baltimore’s jurisdictional reach to follow commercial and residential development as it inevitably expanded over the city line. Baltimore County powers behind the 1948 referendum intended to close the gates around the city, one of the densest in the U.S. at the time. The passage of the measure, as intended, meant the commercial growth, new schools, and residential property taxes in the booming ring of post-WWII suburbs and towns—subsidized by state and federal tax dollars as well as racially discriminatory housing practices and G.I. Bill and FHA lending policies—would forever remain beyond the city/county partition.

It is no coincidence that Baltimore City’s population topped out two years later in the 1950 census and has been shrinking ever since. Subsequently, it has become one of the smallest major cities in terms of square miles. The closing of the city border was part of an even broader political effort that George Romney—the father of the Utah Senator Mitt Romney and Richard Nixon’s first Housing and Urban Development secretary—once characterized as a “high-income white noose” placed around the nation’s urban core. Romney had seen it play out in Detroit when he served as governor of Michigan.

The Baltimore Metropolitan Area, among the wealthiest in the country, continues to see growth—at the exclusion of the city itself.

The Baltimore Metropolitan Area, among the wealthiest in the country, continues to see growth—at the exclusion of the city itself.

The Baltimore Metropolitan Area, among the wealthiest in the country, continues to see growth—at the exclusion of the city itself.

The Baltimore Metropolitan Area, among the wealthiest in the country, continues to see growth—at the exclusion of the city itself.From the approval of the ’48 referendum to the end of the last century, Baltimore County quadrupled its population and surpassed the city. (The restrictive 1924 Immigration Act, which plummented immigration to historic lows until the 1970s, didn’t help cities like Baltimore replace its losses, either.) Not surprisingly, the income gap—virtually nonexistent between the city and county in 1950—widened exponentially. Entire neighborhoods of low-income families were boxed in by segregated public housing that lacked effective public transportation and access to livable wage jobs, which were departing to the county as well, but also for the non-union Sun Belt and later to Mexico and China.

If you wanted to create a city plagued by segregation, you could not have planned it better. By 1993, in his seminal work, Cities Without Suburbs, urban expert and former Albuquerque Mayor David Rusk described Baltimore and other “inelastic” Rust Belt legacy cities, including Cleveland, St. Louis, Milwaukee, Newark, and Camden, as beyond the point of return without dramatic restructuring and regional governance. Targeted “urban” programs such as empowerment zones—no matter how well-intentioned—would never move the needle. Three decades later, the book—and its 1995 follow up, Baltimore Unbound—remains prescient. There were six Baltimore City census tracts where poverty was above 60 percent in 1990; that number had not budged by 2015, the year of Freddie Gray’s death and the subsequent riot and uprising.

Meanwhile, thriving “elastic” cities such as Charlotte, Jacksonville, Raleigh, Indianapolis, Nashville, Austin, Houston, Columbus, Madison, and Albuquerque expanded their footprints anywhere from more than 250 percent to 2,000-plus percent from 1950 to 1990. Baltimore football fans will recall Charlotte and Jacksonville beat them out for NFL expansion franchises in 1993.

“It’s hard to think, looking back, of any single public decision that’s proved to be more important to Baltimore City than that question in the 1948 election,” former City Councilman and current Abell Foundation president Robert Embry told Baltimore years ago. “It was a very shortsighted decision.”

n hindsight, there was frustratingly little coverage of the 1948 anti-annexation referendum. The Truman-Dewey presidential race and 22 other ballot questions—including funding for Memorial Stadium, a term limit for Maryland governors, and a Red Scare measure forbidding officeholders who advocated the violent overthrow of the government—overshadowed the proposal. That said, alert city activists, leaders, and The Sun’s editorial writers recognized the referendum spelled trouble.

A sharp, opinionated gadfly known as “Mrs. B,” a thorn in the side of a half-century of City Hall administrations, called the annexation referendum “ridiculous.” Famous for her election-eve broadcasts, Mrs. B (real name: Marie Oehl von Hattersheim Bauernschmidt) correctly declared passage would “prevent the development of the city.” “Suppose,” she said, “annexation [into the city] had been unlawful and our boundary line would’ve been 25th St.?”

n hindsight, there was frustratingly little coverage of the 1948 anti-annexation referendum. The Truman-Dewey presidential race and 22 other ballot questions—including funding for Memorial Stadium, a term limit for Maryland governors, and a Red Scare measure forbidding officeholders who advocated the violent overthrow of the government—overshadowed the proposal. That said, alert city activists, leaders, and The Sun’s editorial writers recognized the referendum spelled trouble.

A sharp, opinionated gadfly known as “Mrs. B,” a thorn in the side of a half-century of City Hall administrations, called the annexation referendum “ridiculous.” Famous for her election-eve broadcasts, Mrs. B (real name: Marie Oehl von Hattersheim Bauernschmidt) correctly declared passage would “prevent the development of the city.” “Suppose,” she said, “annexation [into the city] had been unlawful and our boundary line would’ve been 25th St.?”

City residents agreed. They voted against the measure by a large count. Baltimore County, however, in what seems a suspiciously high 93 percent turnout looking back, voted in favor by more than 5 to 1. The huge numbers out of the county overrode the city tally and were enough to carry the measure statewide.

Ironically, up until 1853, the city and county had essentially been a single political entity. Initially, it was the city that seceded because of its diverging needs as a burgeoning urban center. By 1952, four years after the approval of the referendum, folks like then City Councilman Frank Flynn were already highlighting that the county was becoming less rural and more suburban and urban. Whatever the distinctions that previously existed, Flynn said, the political boundaries between the two jurisdictions—given their shared geography, economy, and infrastructure—no longer made sense. He noted, as many do today, that county residents took advantage of their proximity to the metro region’s economic and cultural engine, but without paying a fair share of the tax burden. Almost 70 years ago, Flynn proposed considering, if not more annexation into the city, then an even bolder idea—formal reconsolidation.

| ▶ | What if the city had added Catonsville, Rosedale, and Pikesville, local historian Gilbert Sandler once asked. And it had annexed Towson in 1960? |

|---|

Legendary former state comptroller Louie Goldstein floated the same idea in reverse. He suggested the county annex the city. Needless to say, neither plan took root. The subsequent construction of the Baltimore Beltway and the urban expressways of I-83 and I-170, aka The Road to Nowhere, exacerbated existing problems in a way that Councilman Flynn and Mrs. B could not have envisioned.

Baltimore, a mid-century economic giant, losing a third of its population? Unimaginable in 1948. Also, not inevitable. Taken together, the city and county would comprise the eighth largest city in the country today. What’s more, the city's problems would be less concentrated and more manageable. Rusk’s research found areas that created metro governments through consolidation were less segregated by race and class, more fiscally sound, and economically healthier. A plan to reduce school segregation could be worked out if the two systems combined efforts.

Consider if Baltimore had continued to annex parts of the county and maintained its status as a top 10 U.S. city. What if, in the 1950s, as beloved city historian Gilbert Sandler once asked, it had added Catonsville, Rosedale, and Pikesville? Annexed Towson in 1960? What if those light rail stops past Woodberry—Lutherville, Timonium, and Hunt Valley—were in the city? What would it mean to Baltimore’s clout in Annapolis and ability to attract Fortune 500 companies?

Of course, more annexation, or even merging the city and county completely, would not have alleviated all of Baltimore’s problems. But it would’ve had a strong palliative effect. Obviously, neither is politically feasible at the moment. Although there have been relatively recent mergers, most of the last big city/county mergers in the U.S. took place in the 1960s. There’s too much entrenched division now. Also, the metro area has expanded—Anne Arundel, Carroll, Harford, Howard, and Queen Anne’s are part of the equation. But as the recent COVID-19 crisis and its economic fallout demonstrates—along with issues like globalization and climate change—the city’s fate is inextricably linked to the wider world. It’s all the more evidence that Baltimore can’t go it alone in tackling its big problems. We need to act as one metro region if the next half century is going to be different than the last.

One bold idea kicked around in the early years after the passage of the 1948 referendum was a proposal for a federated model of the Baltimore metro region government—with each existing jurisdiction keeping some internal autonomy. In other words, the city and the surrounding metro counties would form something like the consolidated working arrangement that exists in cities like Toronto, London, and New York—think of the five boroughs—as well as Portland, Oregon, and the Twin Cities. Currently, there is an organization, the Baltimore Metropolitan Council, which in theory oversees regional planning, but it avoids controversy and has little power. No doubt few readers have heard of it.

“Someday it will almost certainly be adopted here,” a Sun editorial said of the federated government model proposed in 1956. “The question is, when and how?”

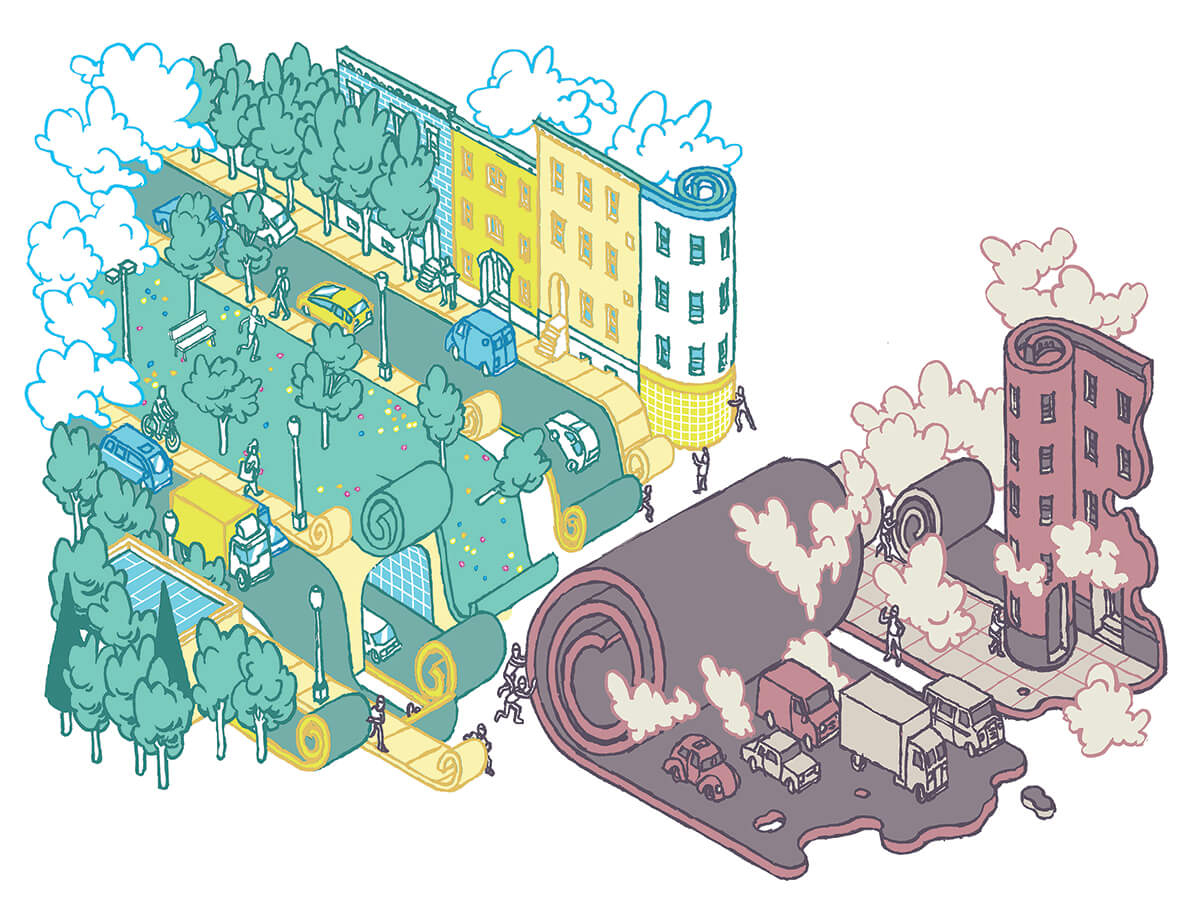

Over the next six pages, we look at 12 bold ideas to move Baltimore forward in the 21st century after decades of segregation, isolation, and stagnation. Some are successfully employed elsewhere, some are new, and several are being explored. One worked here before. The overarching theme is Baltimore will remain stuck in place until its internal physical barriers and its city line—a de facto border wall—are torn down.

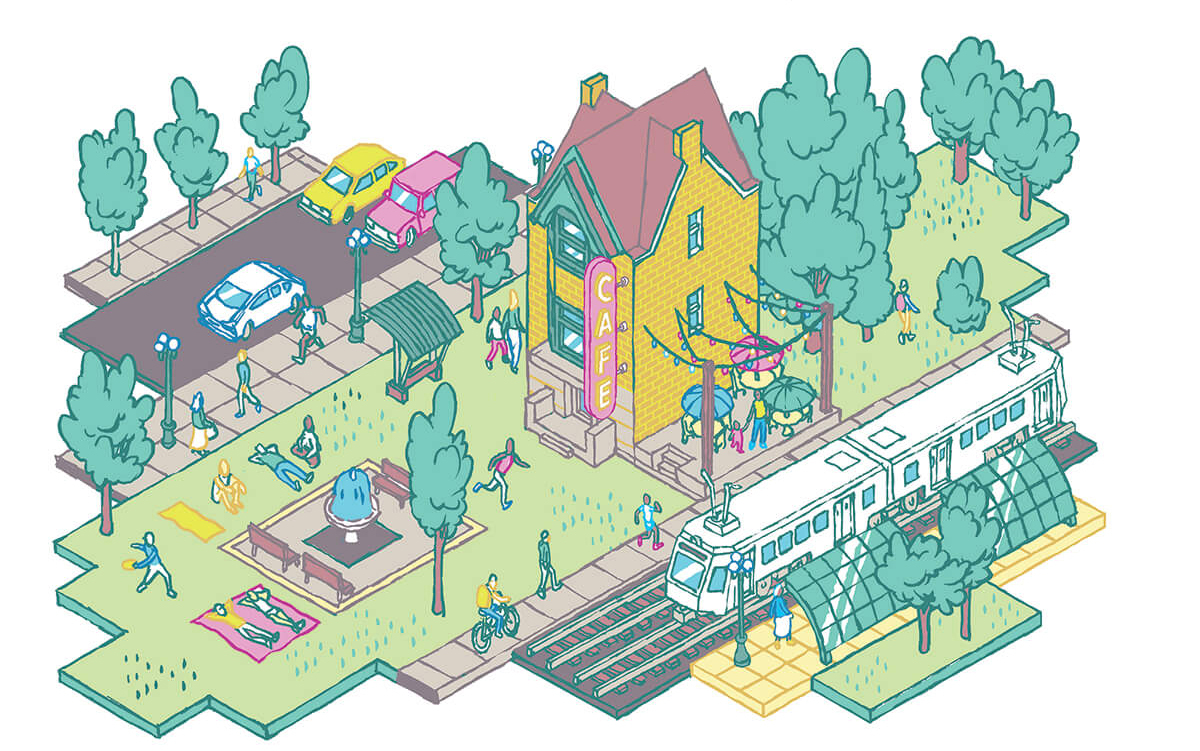

Big Idea: Urban Planning

Baltimore should turn the dangerous JFX into a grand city boulevard and connect downtown and Mt. Vernon with Oldtown and the Eastside.

or most of the country, the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake is remembered because it occurred during the live pre-game broadcast of Game 3 of the World Series at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park. But among public transportation wonks, it’s recalled as a turning point in the effort to undo damage created by two-plus generations of urban highway development. The California DOT intended to repair the busted-up Embarcadero Freeway after the earthquake, warning chronic congestion would ensue with its closure. Instead, then San Francisco Mayor Art Agnos offered a bold alternative: Level the rest of the elevated, 1968-built Embarcadero and replace it with a tree-lined, pedestrian-friendly boulevard and streetcar line. Support coalesced around Agnos’ plan, and the Embarcadero—along with several miles of the similarly damaged Central Freeway spur—was bulldozed. Traffic problems? They never materialized, and public transit trips in the area increased by 75 percent. The number of people living and working near the new Embarcadero boulevard jumped. Meanwhile, the neighborhood’s historic Ferry Terminal was reconnected to its surroundings by new development.

San Francisco is hardly alone today. A stretch of Boston’s I-93 has been buried under a series of parks, connecting downtown to the waterfront. In 2002, Milwaukee tore down a section of its 1960s-built Park East Highway.

Worried about the farmers’ market? There’d be less cramped space available up the street under the Orleans Viaduct.

Now consider I-83, a nearly 60-year-old concrete partition between City Hall and Mt. Vernon and Oldtown. It’s elevated for six blocks over its final stretch downtown before coming to ground-level at Fayette Street. In other cities, well-designed boulevards have increased use of public transit and are shown to be effective at moving JFX volumes of traffic. Liberal pie-in-the-sky? Jay Brodie, past president of the Baltimore Development Corporation, pitched knocking down the JFX in the Baltimore Business Journal several years ago—“Let’s plan now to demolish this elevated, archaic section of I-83”—citing a 2007 study showing the concept was viable.

problem: high city emissions

SOLUTION: car-free streets

▼

Four months ago, a two-mile stretch of San Francisco’s busiest, most iconic artery went car-free, with automobiles banned in favor of pedestrians, bicyclists, taxis, and bus riders. “If there was a street synonymous with San Francisco, it’s Market Street,” Mayor London Breed said during the announcement, describing the historic thoroughfare as “the everyday backbone of the city.” It may seem counterintuitive, but as the Golden Gate City grew from 50,000 to 800,000 residents since Market Street’s construction, it became obsolete for personal automobiles, which take up too much space to transport one person.

Following the lead of European cities, New York banned cars on 14th Street—a major east-west thoroughfare—in October. The endeavor has gone so well it has been nicknamed ‘The Miracle on 14th Street.” Harbor East and Fells Point, which tried an inaugural car-free, al fresco dining night last summer, seem tailor-made for car-free weekends, which reduce emissions, promote public transit, and add to family-friendly walk- and bikeability. But in Baltimore, the game changer would be a Charles Street car ban, which City Councilman Ryan Dorsey suggested while retweeting a Bloomberg story earlier this year that highlighted successes in other cities. “Congestion disproportionately affects vulnerable communities,” Tilly Chang, head of San Francisco’s transportation authority, said in the piece. “Less traffic means improved travel times for public transit, which many people rely on, as well as improved air quality,” which then improves public health.

-Getty

Big Idea: Education

Magnet schools on the city/county line open to students in both districts can be a start.

lthough Baltimore was one of the first cities to desegregate its schools following the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, hopes for an integrated school system evaporated as white families fled to the counties or enrolled their kids in private schools. What ensued we all know: a low-income, hyper-segregated, chronically underfunded system with a graduation rate roughly 20 percent lower than the metro region overall. Why does school integration matter? Students in integrated schools post significantly higher average test scores, are less likely to drop out, and are almost 70 percent more likely to attend a four-year college—even after students’ individual socioeconomic status is taken into account. The good news is the time for action may have arrived.

Baltimore City state senator Bill Ferguson, a former teacher and Annapolis’ new Senate president, has long sought to address the achievement gap created by school segregation. So how to do it?

In 2015, Ferguson authored legislation specifically intended to create diverse, socioeconomically integrated, multijurisdictional schools that would attract kids from the city and the surrounding county school districts. A proposal like that could at least start chipping away at the city’s concentration of hyper-segregated schools. Ideally, it would lead to fuller cooperation between school districts. There are steep political obstacles, of course, which is why the measure didn’t move five years ago. But the state’s new House leader, Del. Adrienne Jones, who is from Baltimore County, could prove a valuable Ferguson ally if she got on board. “More than 50 years of research affirms that poor and minority children perform best when they are not trapped in schools weighed down by concentrated poverty,” retired Johns Hopkins University sociologist Karl Alexander wrote in a 2018 paper. The key to encouraging more families to move to and stay in the city, he adds, “is in growing the base of genuinely high-quality schools that look like all of Baltimore in their makeup.”

problem: too much mayoral power

SOLUTION: charter reforms

▼

First things first. Among the slew of reform measures under consideration by the City Council is a charter amendment that would give the council the authority to oust a mayor for gross misconduct. But that’s just the start. Reform is needed of Baltimore’s so-called “strong mayor” system, which places more power in our top elected official than almost any mayor in the country. For example, only the mayor can make additions to the city budget during negotiations; City Council can merely seek cuts. In 2016, Councilman Bill Henry, currently running for comptroller, sponsored a change that would allow council members to make additions if the money was subtracted elsewhere. It was vetoed, not surprisingly, by former Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake.

Which brings us to another key reform—making it easier for the council to override vetoes. The current threshold requires three-fourths of the council, 12 of 15 members—a near-impossible margin for decades—to override. A two-thirds vote, the margin required in Congress, would require 10 votes. Also needed: the closing of a scheduling loophole that allows the mayor to avoid override votes entirely. Currently, a dozen-plus amendment bills have been introduced, but getting these three on the ballot in November is a must. Finally, the General Assembly must give Baltimore the right to implement a ranked-choice voting system. With more than 20 Democrats running for mayor, there’s every chance the next mayor will win the Democratic primary, and, for all intents and purposes, the city’s highest office, with less than 25 percent of the vote.

Big Idea: Urban Planning

The need for a transformative East-West line remains.

hortly after taking office, Gov. Larry Hogan quashed the city’s long-anticipated Red Line, the federally approved $2.9-billon east-west subway, without producing as much as a single formal review of the project. Hogan later spread the state’s share of the savings on various, and perhaps ethically questionable, highway projects. So, while roughly 30 percent of Baltimore households don’t have access to a vehicle, the city remains handicapped with a single subway track and single north-south light rail line that plods through downtown. Ultimately, building the Red Line is about more than just providing a way to get from West Baltimore to East Baltimore (and linking residents to thousands of jobs at the Social Security Administration and Johns Hopkins Bayview), critical as that is. It’s also central to connecting underserved city residents to more destinations in the broader regional transit network. Plus, it has the potential to spark creative investment in the Road to Nowhere corridor (see illustration), the long-since scrapped urban highway that was supposed to connect I-70 to downtown in the 1960s. “The Road to Nowhere broke up West Baltimore communities that are still trying to recover two generations later,” Glenn Smith, 71, vice president of the Baltimore Transit Equity Coalition (BTEC), told Baltimore four years ago. “My family was one of those displaced. Those 19 stations along the Red Line would’ve brought considerable investment to the community.” Smith noted that studies show long mass-transit commute times are linked to unemployment in low-income neighborhoods.

The BTEC proposes that the state legislature create a regional transportation authority, similar to the Washington Metro Area Transit Authority, the operator of the D.C. Metrorail system, which could raise fees, taxes, fines, bonds, and licensing as done in numerous regions around the country.

problem: collapsing infrastructure

SOLUTION: leverage city municipals

▼

Baltimore’s infrastructure problems are legion—an ongoing sewage system crisis, the state's oldest schools, lead paint, a lack of healthy affordable housing, streets collapsing under the weight of age and heavier rainfall, and low-income neighborhoods suffering from air pollution and the heat-island effect. Some news? Two years ago, the city partnered with the Chesapeake Bay Foundation to create Environmental Impact Bonds—also known as “green bonds,” and part of a World Bank initiative. They allow investors to pay for projects that minimize pollutant runoff and heal streams and the Inner Harbor and recoup their investments if the projects are successful. The Department of Public Works will use up to $6.2 million in those bonds to help construct 115 bioretention facilities and remove impervious surfaces. It’s an example of creative infrastructure funding the city needs more of.

The time has also come for the city to fully leverage its AA long-term bonding restored, to her credit, by former Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake six years ago. (The last time Baltimore’s bond rating was so high was 1963.) It should be used to fund city projects that will improve public health and help stave off the worst effects of climate change, and not just float Inner Harbor and Port Covington development projects. Finally, crowdfunded smaller municipal bond projects have launched more than 1,200 infrastructure campaigns elsewhere since 2010. In Denver, the city issued $500 “mini-bonds” limited to residents of Colorado as a means of funding certain infrastructure projects. Adding to Baltimore’s bicycle network and expanding broadband—at-risk communities remain separated by a widening digital divide—are potential uses.

Two years ago, the city partnered with the Chesapeake Bay Foundation to create Environmental Impact Bonds. | ◀ |

|---|

-John Patterson

Big Idea: Public Safety

Baltimore needs to follow Chicago’s lead.

emember when Chicago and Baltimore were linked in headlines for both cities’ skyrocketing homicide rates? In 2015, in the aftermath of the death of Freddie Gray, Baltimore suffered one of its most deadly years. Five years later, there’s no end to the violence in sight. After some if its lowest homicide numbers in decades in the early 2010s, Chicago’s homicides spiked 56 percent after unarmed 17-year-old Laquan McDonald was shot 16 times and killed as he walked away from police. The dashcam video of the shooting, finally released in late 2015, sparked widespread protests and exposed longstanding grievances over policing in Chicago. Sound familiar? There’s more. In 2017, a damning Department of Justice investigation concluded Chicago police officers were poorly trained and quick to turn to excessive and deadly force, most often against citizens of color, without facing consequences. Since? Chicago’s homicides have fallen nearly 37 percent. After 2016, Chicago realized it needed an all hands on deck approach to address gun violence, and, critically, the effort had to be coordinated—no more working in silos.

More than 40 foundations and funders now make up the Partnership for Safe and Peaceful Communities, a philanthropic community that works together to identify and support, with nearly $75 million since its inception in 2016, community-designed, evidence-based solutions that the public sector can use as a blueprint to battle the public health crisis that is gun violence. Among the key projects funded by the partnership is READI Chicago (Rapid Employment and Development Initiative), an ambitious 24-month-long transitional job, behavioral therapy, and training program that engages those at the highest risk for gun violence. Baltimore’s ongoing Ceasefire initiative has demonstrated our everyday citizens are willing to do their part, and Chicago’s example shows gun violence reduction is doable. Anti-blight, anti-poverty, and school investment also can’t be ignored and reduce violence in the long run. But in the short term, reducing the homicide rate requires focused attention on the relatively small group of people likely to use a firearm.

problem: kids need a place to go for activities

SOLUTION: state-of-the-art rec centers

▼

In the 1980s, Baltimore City operated more than 100 rec centers. Today, it’s 44, most of which are 50 to 60 years old and spent the past few decades closed on weekends. The physical deterioration and shuttering of Baltimore’s rec centers has been perhaps the most glaring example of the city’s misplaced budget priorities. Over the past 30 years, Recs and Parks funding has remained nearly flat while the police department's budget has tripled. Recently, corrective steps are being made, but they must continue. The first new rec center in more than a decade was built in 2014. West Baltimore’s Crispus Attucks and Harlem Park rec centers both recently reopened. And last September, city rec centers also opened on Saturdays for the first time since the 1970s. Other new efforts include the planned Middle Branch Fitness & Wellness Center, situated near Cherry Hill and the Gwynns Falls Trail, which will include a turf field for football, lacrosse, and soccer, and an outdoor pool. Also in the works is a nearly 50,000-square-foot Cahill Fitness & Wellness Center, which will be built into the 1,000-acre Gwynns Falls/Leakin Park area. Reginald Moore, executive director of Recreation and Parks, now wants to create a state-of-the-art regional facility that will not just pull kids from the city, but host elite basketball, cheerleading, robotics, and gaming competitions. “The goal,” Moore says, “is that Baltimore kids won’t have to travel to participate in AAU basketball, cheerleading, and gaming tournaments. We want people to come here, to our amenities.”

-Shutterstock

Big Idea: Politics

No way around it, the city and county need to merge.

ashville, the first city of country music, is also a pioneering example of progressive governance. A long-segregated city—just like Baltimore—Nashville also saw its population decline at the outset of the post-World War II suburban boom. But in 1963, after a decade of political wrangling, Nashville’s civic leaders worked together to consolidate local governments within Davidson County to create the Metropolitan Government of Nashville. Since the merger, Nashville’s population exploded from just over 170,000 to nearly 700,000 today. Similarly, Jacksonville, Florida, consolidated with Duval County in 1968 after the industrial city began experiencing its own symptoms of downtown decline. Indianapolis, led by Republican mayor and future U.S. Senator Richard Lugar, merged with surrounding Marion County in 1970—known colloquially as “Unigov”—through an act of the state assembly. More recently, in 1997, Kansas City, Kansas, consolidated with Wyandotte County and ever since has seen its population grow. Other consolidated city governments with populations larger than 500,000 include the city and county governments of San Francisco, Denver, Philadelphia, Boston and Suffolk County, and, of course, New York and its boroughs. All of have flourished in recent decades (even Philadelphia’s population jumped by 4 percent in the last count). Merging governments isn’t that hard structurally—most have an elected chief executive, a fairly large district-member council, plus at-large members.

Baltimore City’s population will never fully recover, for example, as long as its effective property tax is far and away the highest in the state and one-third higher than Baltimore County. Yes, city/county consolidations can take a generation or two to make substantial impact. But there is no quick fix. “The public services efficiencies [police, fire, sanitation, sewage, water, etc.] are important,” Baltimore native Spencer Levy, chairman of the international real estate services company CBRE, said in a Sun op-ed last year while making the consolidation case, “but mitigating reasons for urban flight—largely schools, taxes, and crime—are paramount.”

Merging Baltimore City and Baltimore County is no magic wand, but it offers the only solutions to addressing the city’s stickiest problems. |  | ◀ |

|---|

problem: corruption

SOLUTION: ethics reforms

▼

If only city corruption was limited to the crimes of recent mayors Sheila Dixon and Catherine Pugh. In 2018, former state Sen. Nathaniel Oaks pleaded guilty to accepting bribes from an FBI informant posing as an out-of-town developer. Earlier this year, former state Del. Cheryl Glenn pleaded guilty to accepting bribes to help a cannabis company. In March, the city Office of the Inspector General (OIG) found Comptroller Joan Pratt voted 30 times to approve spending involving organizations that she appears to have relationships with.

The endemic corruption within the police department continues—at least 20 officers arrested, suspended, or convicted last year. Meanwhile, The Sun reported police overtime cost the city nearly $50 million last fiscal year, and the Inspector General’s office found the Bureau of Solid Waste more than tripled its allotted overtime budget in fiscal year 2018. We could go on.

Councilman Ryan Dorsey introduced a bill last year that would move the ethics board—responsible for enforcing conflict of interest rules and maintaining city employees’ financial disclosure records—to the Inspector General’s office, which was recently granted independence. Dorsey has also introduced legislation prohibiting city officials from retaliating against whistleblowers. Both efforts need to move forward, as does legislation introduced by Gov. Larry Hogan in Annapolis that will increase fines for bribery, require that convicted lawmakers forfeit their taxpayer-funded pensions, and expand prohibitions on misuse of confidential information by public officials. But it’s just a start if Baltimore’s faith and hope in its elected officials and city agencies are ever to be regained.

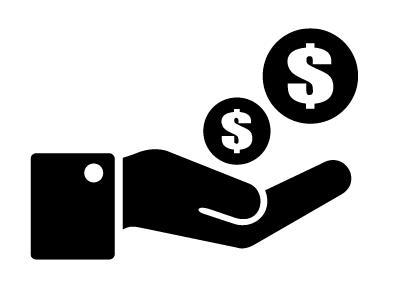

Big Idea: Transportation

Build out the Maglev and Penn Station to keep and attract new, younger residents.

he biggest promise of the 300-plus-mile-per-hour superconducting maglev, touted as the world’s fastest train, isn’t cutting the commute to Washington to 15 minutes, including a stop at BWI Airport—although that would be amazing. It’s that the entire trip from D.C. through Baltimore, Wilmington, and Philadelphia to New York—including stops at airports in Philly and Newark—would take one hour. Baltimore has a potentially strong transportation network, including BWI, I-95, I-70, I-695, and the Port of Baltimore. But for Northeast Corridor commuters, the options remain crowded highways or an outdated regional Amtrak system. The city sits uniquely poised to take advantage of the first-of-its-kind high-speed rail in the U.S. One reason is it could help the city’s two- and four-year college-graduate retention rate—at 44 percent, the city ranks among the lowest of the largest metro areas in the country (and that was before the upsurge in violent crime in recent years was taken into account). Baltimore also presents a strong option in the Northeast Corridor for remote workers because of its comparatively low cost of living, according to a more recent study. Finally, building the maglev is estimated to create 74,000 construction jobs in the state, which is why its has won support from Maryland NAACP leaders.

Meanwhile, it’s important to keep in mind that this should not be, and can’t be, a choice between moving forward with the maglev or building the Red Line or upgrading Amtrak and the MARC. The cost of a maglev ticket alone will certainly price out many residents. The city needs all of the above. Each transit option serves different purposes and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. But it’s also important that renovation and expected development around Penn Station, which help link West and East Baltimore, continues as planned.

problem: unaffordable city housing

SOLUTION: bring back the $1 house program

▼

City Councilwoman Mary Pat Clarke remembers the city’s famous “Dollar Houses” program of the 1970s, which offered incentives for homesteaders to claim vacant city houses for next to nothing. The initiative was the brainchild of Mayor William Donald Schaefer’s then housing commissioner, current Abell Foundation president Robert Embry. It matched qualifying middle- and low-income homeowners with below-market-rate rehab loans and home improvement professionals, and it was a hit in neighborhoods like Otterbein, Federal Hill, Fells Point, Pigtown, Ridgely’s Delight, and Butcher’s Hill. “Part of why the ‘dollar houses’ were a big deal was the idea itself—a spirit of possibility took hold in the city,” Clarke says. (One of those attracted by the potential of the program was future developer Bill Struever, just out of college.) The project proved most effective in Otterbein, where a significant number of homes were clustered.

Today, with 16,000 vacant properties in the city and the population falling below 600,000 for the first time in a century, Clarke has been trying to revive the program with a local group called “H.O.M.E.S”—Homeownership, Opportunity, and Mentorship for Economic Success—and got a resolution passed three years ago to study the plan. So far, city officials have told her that the obstacle is finding and pulling together revivable, vacant, city-owned properties in blocks where investment is likely to pay dividends. Clarke doesn’t believe it’s an insurmountable hurdle. “More than anything else, ‘Dollar Houses’ is the one I’d like to see get started before my time is up,” says Clarke, who is retiring at the end of this year.

“Part of why the ‘dollar houses’ were a big deal was the idea itself—a spirit of possibility took hold in the city.”. | ◀ |

|---|