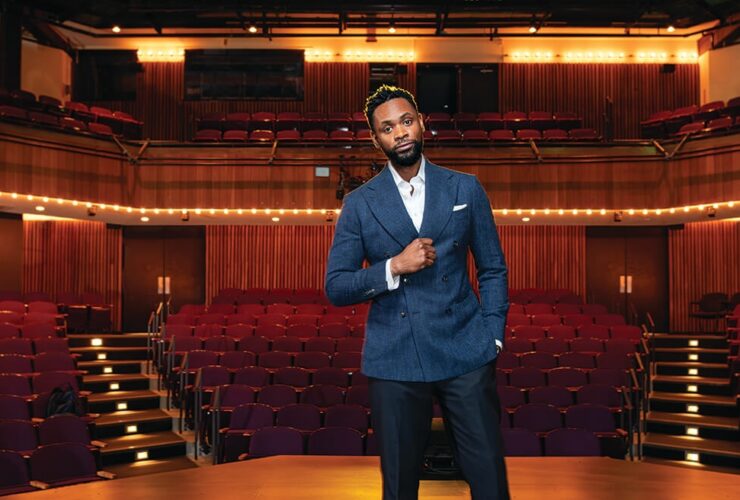

Calvin’s Calling

Exelon exec has flipped the switch on money and leadership for multiple city causes.

GameChangers

Calvin’s Calling

Exelon exec has flipped the switch on money and leadership for multiple city causes.

Christianna McCausland

Photography by Frank Hamilton

Fresh marketing campaigns about their community involvement, new Baltimore-boosting billboards, words of sympathy, and small donations to this or that urban cause.

In many cases, that was the response of the local business community to the uprising in 2015 following the death of Freddie Gray. But it wasn’t enough for Calvin Butler.

“There are not many people like myself sitting in the top positions of companies; if I can be a role model to them, that to me is a driving force for why I do what I do.”

The St. Louis native had been named the CEO of BGE just the year before—he has since been promoted by parent company Exelon—but he was already plugged into the city, its struggles, and its capacity to make itself stronger. And the unrest put him into action.

By his own admission, Butler is not a patient man, but that’s paid off for Charm City. After the unrest, he immediately thought of what he and BGE could do to effect a long-term sustainable change—not just write a check.

“What was interesting about [the Freddie Gray uprising] was a lot of people were giving a little money here and there, but at the end of the day, if people don’t have jobs, if people don’t have hope, they’re going to do what they have to do,” Butler says. “The city felt, in real time, what happens when people feel as if they’re being suppressed.”

Since Butler joined BGE, the company has given more than $30 million

to area nonprofits.

Butler knew there were job opportunities in his energy sector. He also knew there was opportunity in construction. Over the course of several Saturdays, Butler met at Atwater’s off York Road with Whiting-Turner CEO Tim Regan. Together, they mapped out an idea on the back of a napkin.

“We recognized people who feel disenfranchised lack a couple of things: mentors, social capital, and opportunities,” says Butler, who, in December, was put in charge of other Exelon utilities as well. “We didn’t want to create something new because there are already many organizations in the city doing great things, so we went to the community in West Baltimore and asked them what we could do.”

The initial idea evolved into TouchPoint, co-founded in 2017 by BGE and Whiting -Turner. Located in Mondawmin, it brings together three pre-existing, high-performance nonprofits—Thread, Center for Urban Families, and Baltimore Corps. According to Sarah Hemminger, CEO of educational outreach nonprofit Thread, TouchPoint nurtures the existing talent pipeline in the city “from cradle to career,” by bringing nonprofits, community partners, and all their associated audiences together to volunteer and collaborate across silos.

“TouchPoint is an unprecedented example of a space where Baltimoreans come together across lines of difference to build relationships and access opportunity,” Hemminger says.

This type of large-scale, programmatic philanthropy has become a signature of Butler’s approach to outreach. In addition to co-founding TouchPoint, Butler also used the Freddie Gray uprising as a catalyst to develop BGE’s Smart Energy Workforce Development program. Working in partnership with four Baltimore City and County vocational schools, BGE offers field trips to its facilities and provides summer internships to high-school students. Since its inception in 2017, 11 full-time BGE employees have been hired from the program.

“I recognize our leadership responsibility as a corporate citizen because we’re not packing up and going anywhere. So what do we do with that responsibility?”

Since Butler joined BGE, the company also has given more than $30 million to area nonprofits. Following Butler’s lead, the employees at BGE, who nominate their own “Employee Cause Initiative” each year, have seen an uptick in their dollars raised year-over-year. Over his tenure, employees have also given more than 100,000 service hours.

Butler has overseen large contributions, partnering with the Cal Ripken, Sr. Foundation to open Eddie Murray Field at BGE Park in West Baltimore, where the oldest continually operating African-American youth baseball league plays. And under his leadership, BGE became a founding lead sponsor for Light City. He’s also made small contributions that make a lasting impression, like painting BGE’s storage tanks with murals to beautify the southern entrance to the city.

“These are things that are outside the box of what your traditional utility might do,” says Butler, who says his commitment to philanthropy comes from his own experience with mentors.

BGE’s Butler was one of the co-founders of TouchPoint.

“I always talk about finding your purpose and, for me, as an African-American business leader, my purpose has been to impact young people, specifically kids of color,” he says. “There are not many people like myself sitting in the top positions of companies; if I can be a role model to them, that to me is a driving force for why I do what I do.”

Of course, Butler is a businessman, and he does not shy away from underscoring that BGE’s growth is dependent on a strong, healthy city and surrounding area. He believes it’s also good business to create a workforce at BGE that is diverse and inclusive. Currently, BGE customer satis- faction is at an all-time high; in June, BGE was recognized as one of the nation’s most trusted utilities, according to industry- review analytics firm Escalent. And Butler says it’s no coincidence that the company’s peak performance is coinciding with its commitment to employee diversity.

“For the last five years, we’ve received the highest customer satisfaction in our 200-plus year history, best financial performance, and highest reliability, and, to me, the team we’ve put together, which is the most diverse in BGE’s history, is indicative of what can happen when you hire diverse people of diverse backgrounds, talents, and skills, and enable them to do their jobs.”

At the same time, Butler has radically improved BGE’s spending with women-, minority-, and veteran-owned businesses (WMVBs). When he joined the company, it was spending roughly 14 percent with these entities; in 2019, BGE committed 40 percent to WMVBs.

The example set by the utility captured the attention of other local institutions. Ronald Daniels, president of The Johns Hopkins University, worked with Butler to bring the Roca anti-violence program to Baltimore. Says Daniels, “Calvin has the rare ability to understand the complexity of the city’s needs and then summon up the moral, strategic, and financial savvy to respond to those needs in a compelling way.”

“When there’s a challenge that crops up in the city,” Daniels adds, “Cal is at the top of my speed dial to figure out how we can make a difference.”

In the wake of Freddie Gray, Johns Hopkins also looked into how it could have a sustainable impact. Understanding that strong local businesses would enable much-needed job growth, Hopkins wanted to be more intentional in its support of local and WMVBs in its procurement, construction, and hiring.

HopkinsLocal, as the program became known, drew on the BGE playbook. Then Mike Hankin, president and CEO of money management firm Brown Advisory, suggested amplifying the impact across other city businesses. Daniels and Butler answered that call in 2016, co-founding BLocal, a coalition of city businesses committed to supporting local businesses and workers. It now has 28 partners including T. Rowe Price, Legg Mason, KPMG, Under Armour, The Cordish Companies, Howard and M&T Banks, and DLA Piper. In their first year, BLocal businesses spent $73.8 million with WMVB vendors in construction and purchasing, plus another $2.3 million in non-construction purchasing; and as of late November of last year, the coalition had spent more than $280 million. In addition, BLocal has encouraged the hiring of more than 1,700 local employees.

“Freddie Gray was a cry, a call to do better as a city,” says Butler. “Do I think we’ve made progress? Yes. Do I think we’re close to being there? No, because as long as we have high unemployment rates in pockets of the city, high healthcare disparity, as long as kids in certain zip codes don’t get the same level of education, there’s a problem.”

He’s optimistic that breaking down silos and providing opportunities for young people and their parents will lead to prog- ress. Given BGE and parent firm Exelon’s size and reach, he anticipates playing an expansive role in radical change, not only in Baltimore but also across BGE’s wider customer area.

“I recognize our leadership responsibility as a corporate citizen because we’re not packing up and going anywhere. So what do we do with that responsibility?” Butler asks. “I think leaning in and not only being a trendsetter but a thought provoker, an impact player, is who we are.”