Reaching Back

Three local luminaries weigh in on the city, on their calling, and on Baltimore’s kids.

GameChangers

Reaching Back

Three local luminaries weigh in on the city, on their calling, and on Baltimore’s kids.

Interviews by Ron Cassie

Photography by Erin Douglas

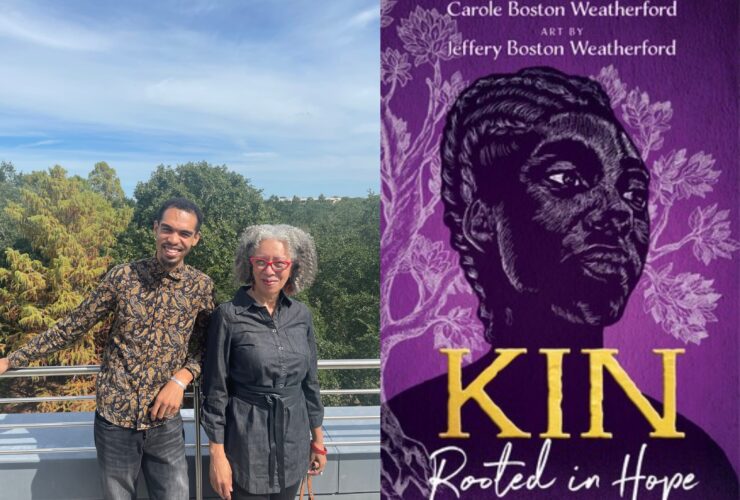

The Writer

D. Watkins, 38, born and raised in East Baltimore, is an editor at large for Salon magazine, a Salon podcast interviewer, a University of Baltimore lecturer, and the New York Times best-selling author of The Beast Side: Living (and Dying) While Black in America, The Cook Up: A Crack Rock Memoir, and We Speak for Ourselves: A Word from Forgotten Black America. He holds a master’s degree in education from The Johns Hopkins University and an MFA in creative writing from the University of Baltimore.

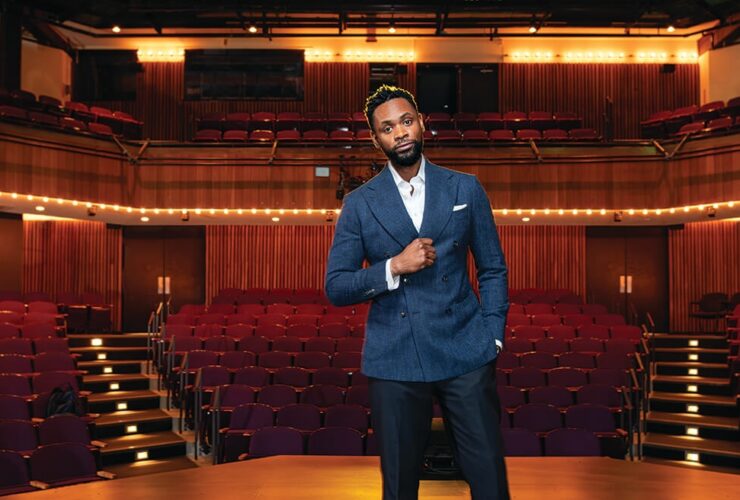

The Photographer

Devin Allen, 31, is a self-taught, professional photographer from West Baltimore. He gained national attention when Time magazine published his black-and-white image from the Baltimore Uprising on a May 2015 cover. His photographs were collected into the book A Beautiful Ghetto and have appeared in New York Magazine, Aperture, The New York Times, and The Washington Post, and are among the permanent collections of the National Museum of African American History & Culture, the Reginald F. Lewis Museum, and the Studio Museum in Harlem.

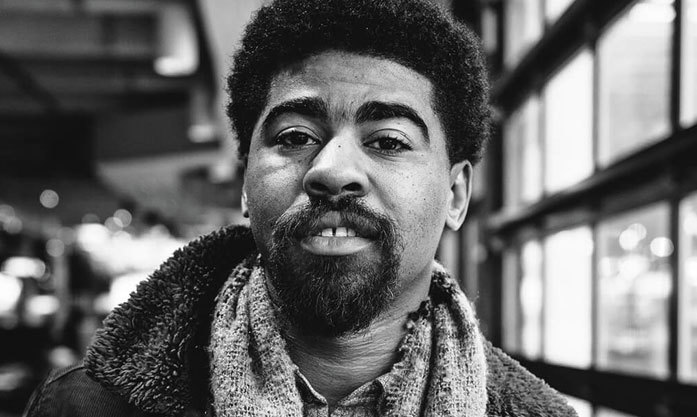

The Poet

Kondwani Fidel, 26, is a Baltimore native, poet, essayist, and the award-winning author of Raw Wounds and Hummingbirds in the Trenches. His work has been featured in The Washington Post, The Atlantic, and The Root. In 2018, he received the Civil Rights Literary Award from the Baltimore City Office of Civil Rights. In 2019, he was awarded Community Law in Action’s Inspiring Voices award, and his biofilm was nominated for Amazon’s 2019 All Voices Film Festival.

➔ Writer D. Watkins, photographer Devin Allen, and poet Kondwani Fidel have each earned national praise for their personal, often Baltimore-inspired work. But rather than head for the bright lights elsewhere, the three close friends have remained here, at least in part, because of their shared commitment to the city’s youth, which includes donating countless hours, as well as books, to local schools. To find out what makes them tick, we met them at R. House in Remington and asked about how they broke in as artists, their work in schools—and what Baltimore students need to succeed.

“There weren’t people, writers in Baltimore, with whom I could connect, or directly learn from, until after I was already in it.”

Bmag: D, can you go first and talk about starting out as a writer and the challenges coming from outside the traditional white publishing networks? Did you have a mentor?

D. Watkins: There weren’t people, writers in Baltimore, with whom I could connect, or directly learn from, until after I was already in it. You think about that because maybe your career could’ve started five years earlier if you knew somebody. In our industry, more people get published because of who they know, rather than their straight work. You know someone, boom. You don’t, you can send the best s--- out to magazines for years and it will just sit at the bottom of a stack.

Devin Allen: That’s how it was for me. I’d shoot stuff, shoot protests, send it out for free, just ask for a credit, and not even get a reply to an email. I did get a reply once from the City Paper, but nothing from The Sun. Not until I got the cover of Time, and then they wanted to interview me [for my Reginald F. Lewis Museum show]. At that point, I didn’t want anything to do with them, but the museum wanted me to do the interview. I did it, but not until they apologized.

Kondwani Fidel: After I graduated [from Virginia State University] in 2015, I traveled around the city doing spoken word and got a good response. I dropped this poem called “The Baltimore Bullet Train” with a video and it got like 20,000 views on YouTube. Then, I finished my first collection of poetry and my first book, and teachers started asking me to come to their classes. Everything grew from there. I teach now, perform, do workshops.

Bmag: You each spend a lot of time in public schools, making hundreds of visits. What do you hope to accomplish?

Watkins: I was struggling to get published, but then my first Salon article came out, my second Salon article, then a City Paper article …and Baltimore City school teachers started reaching out to me. While these articles were doing well on the internet, kids in schools had started reading them, too. I didn’t think much about reading coming up. It wasn’t really my thing and it wasn’t until later that I realized how much I loved reading and that I wanted to be a writer. I had never met a person who looked like me who was a writer, and seen them come hang out in school when I was in school.

Allen: You got to go and think, “I’m going to change someone’s life today.”

“…I started visiting these schools, kids would say, ‘I didn’t think I liked poetry until I heard your work’ and ‘Yours is the first book I read cover to cover.’ I looked at the things that helped transform me and it was texts that were relatable.”

Fidel: At first, I didn’t understand what [teachers] wanted from me. I didn’t have a degree in education. But when I started visiting these schools, kids would say, “I didn’t think I liked poetry until I heard your work” and “Yours is the first book I read cover to cover.” I looked at the things that helped transform me and it was texts that were relatable. I fell in love with reading through a college professor’s readings at Virginia State…so I started thinking about how I felt slighted in high school. I started thinking it’s part of my obligation to get students excited about reading and get them engaged in literature at a younger age than I was exposed to it.

Bmag: What obstacles have you run into working with students?

Watkins: One teacher, who worked on the curriculum, told me he was pretty sure they were going to put The Beast Side on the required reading list. Kids were already reading it and stealing copies from classrooms, which was crazy and great because, by that time, I already had a New York Times bestseller to my name and a presence in Baltimore City schools. Then, they denied it because of the profanity.

Allen: A lot of times, there’s too much politics working with schools. Same with nonprofits. It takes too much time. So I’ll go to a rec center and use my own money, or get my own grant. At the Kids Safe Zone, after the Baltimore Uprising, I got a grant from [music mogul] Russell Simmons, put the cameras in my trunk, and started working with the kids. Same with the St. Francis Center. MICA wanted to do a show with some of my work and I told them they could use my work, sure, but, “How about donating some point-and-shoot cameras” and I did a workshop. I’ve given away almost 500 cameras.

Watkins: The bottom line is, I need to be in schools. They read one of my books, or one of Konnie’s books, and they like it and meet us. That might turn them on to another book. And now, they’re not only loving our Baltimore stories, which are their own stories, they’re learning about other places from different stories and they are in the game.

Bmag: A common theme is Baltimore students need to be reached with material that will engage them. Maybe don’t start with traditional English or world literature?

Fidel: Things Fall Apart [a 1958 novel written by Nigerian author Chinua Achebe] is a good book, but it was hard for me to connect to that book in high school. I didn’t know anything about Africa and the complicated issues he was dealing with. It was foreign. But imagine if you use the same themes that were in that book, but it was based in Baltimore, and the writing had Baltimore vernacular—I probably would’ve engaged in it. Not to say we didn’t have artists and writers who shared the same skin complexion as me, but those Baltimore experiences, I didn’t see them in anything we were being taught.

Watkins: If they read [Fidel’s book] Hummingbirds in the Trenches, it is going to hit them. It’s an authentic story from a person that is here and accessible and loves them, and it just bleeds through all the work.

Bmag: Do you believe writing, poetry, and photography help students dealing with trauma?

Fidel: When I speak about painful experiences, it lets students know they aren’t alone. Teachers and adults say things like, “I don’t know if they are ready for that conversation,” whether it’s about trauma or violence or people getting their brains spilled on the curb. How are they not ready for the conversation when they witness it firsthand? They read my work, and they’re like, “Okay, it’s normal for me to feel depressed and it’s normal for me to cry. It’s normal for me to be upset with what’s going on in my community and in the world.”

Bmag: You are all also active on social media. Why is that important?

Fidel: We share a lot of things the students share, we share a lot of the same interests, but we still travel to Japan, to London, wherever, and we do all those things and come back to Baltimore.

Bmag: Why do you think Baltimore students are attracted to your work? Or to writing, poetry, and photography in general?

“You would be surprised how many kids grew up in the ’hood that have few photographs of themselves and their families. Then, when they take a photograph, there’s that moment to look at it and self-reflect.”

Allen: You would be surprised how many kids grew up in the ’hood that have few photographs of themselves and their families. Then, when they take a photograph, there’s that moment to look at it and self-reflect. They see their friends, too, and it opens up communication on a different level. It allows them to digest what’s around them and regurgitate what’s around them to the rest of the world. Kids walk past addicts and vacant houses every day, it’s nothing to them, but when they start photographing it, it’s like, “Oh, this s--- isn’t normal.” They’re just so desensitized to it. It’s a stress reliever and a conversation starter.

Fidel: Baltimore is an uncanny, peculiar city. For them to be able to look at photographs, to read poems and books from Baltimore artists who share the same experience, teaches them how to build a life like we actually face, not a fairy-tale life.

Bmag: What can schools and artists do to help students?

Watkins: If a person is an artist in Baltimore, with world-wide notoriety or not, and they are willing to come talk about the beauty of art and the beauty of creation, then schools should work hard at connecting them with kids and building those relationships. There should be fellowships and stipends to purchase their work and bring that into schools. They waste so much money on stuff that doesn’t matter.

Allen: I didn’t start until I was 25 and I taught myself. I can only imagine if I knew a photographer and I started at 16, 15. Photography is not even in public schools. I talk to white photographers and they’re going to private schools that have darkrooms. Photography transcends so many different spaces. Look at social media. Photography needs to be in schools.

Fidel: They need to teach rap and spoken word in schools.

Bmag: Devin, from Instagram, etc., do students recognize you when you visit? Do they know the Time magazine cover? Or about shooting for Under Armour?

Allen: They don’t care about the Time cover. Once they know I shoot for Under Armour and I shoot Steph Curry, it’s over. They’re hooked. One girl, at a school I hadn’t been to, told The Baltimore Sun that I deserved a statue and so I popped up on her and visited her class. She was nervous, but the teachers and kids were all taking pictures with me. It was dope.

Bmag: What do you think would surprise people from outside about city students?

Fidel: All these kids want to learn, they want to be creative, and they want to be engaged.

Bmag: What else do they need?

Fidel: The best that we have to offer. They see these other schools, private schools in the city, and they see what they get—and they’re not even getting functioning heat and air conditioning. Then, we deny them representations of themselves. Their experiences are scarcely mentioned or omitted completely—and people wonder why some act out. If this country and this city know the importance of education—where the best education can lead you and where a lack of education can lead you—why is it that we give the black and brown students that live in these underserved areas the least?