Health & Wellness

IT’S FRIDAY MORNING IN LATE JULY and Dr. Caroline Burley is bright and cheerful, buoyed by the Thai tea in her YETI thermos and the fast-approaching “Golden Weekend.” That’s intern-speak for two glorious days off in a row, a welcome and rare reprieve from the grind of the internal medicine residency program at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center.

“I hope to get in some pool time and hang out with my friends,” says Burley, as she leads the way into a small conference room on the Bayview campus. “I might get really crazy and finish a book I’ve been reading.”

Free time is at a premium for Burley, but she has a sliver of it to chat before a lunch-and-learn didactic training on infectious diseases and a run of patient appointments scheduled to wrap up by late afternoon.

Is that realistic? “No,” she laughs while thumbing through her iPhone’s daily planner. “I’ll probably head home around 6:00, if I’m lucky.”

As a child growing up near Newark, New Jersey, Burley loved talking to older adults, soaking in their wisdom and the stories they told. Those experiences, along with her love of biology in high school and, having been raised Catholic, her belief in its tenet of living in service to others, sparked an interest in medicine.

But Burley doesn’t come from a family of physicians and it’s impossible to know what being a doctor is truly like until you walk a mile in their slip-resistant clogs. So before committing to medical school she signed up for a student program that allowed her to shadow several practitioners in multiple specialties.

Burley was surprised by how many docs cautioned her to think twice about following in their footsteps. “They were happy with their careers,” she says, “but made it clear that medicine is the wrong choice if you’re doing it for money or prestige. You need to feel like it’s the only thing you can ever imagine doing, a calling you can’t ignore.”

Practicing medicine these days is a veritable minefield. Antivaxxers have allowed measles to make a comeback. Major health insurers are prioritizing profits over patient care. Incidents of violence against health care workers are increasing, and rates of physician burnout and suicide are troubling.

The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) reports that the number of medical school applicants has declined for the third consecutive year and predicts the U.S. will face a deficit of 86,000 physicians by 2036. The AAMC presents additional figures that suggest financial concerns create barriers to pursuing a career in medicine: The class of 2025’s median four-year cost of attending medical school was $286,454 for public schools and approaching $400,000 for private schools. (Studies show it takes between six-10 years on average to pay off school.) Fifty-five percent of students who responded to a post-MCAT questionnaire in 2022 said the cost of applying to medical school discouraged them from applying.

Today's health care environment makes you wonder if medicine’s calling is loud enough to be heard or if current and potential physicians are even listening.

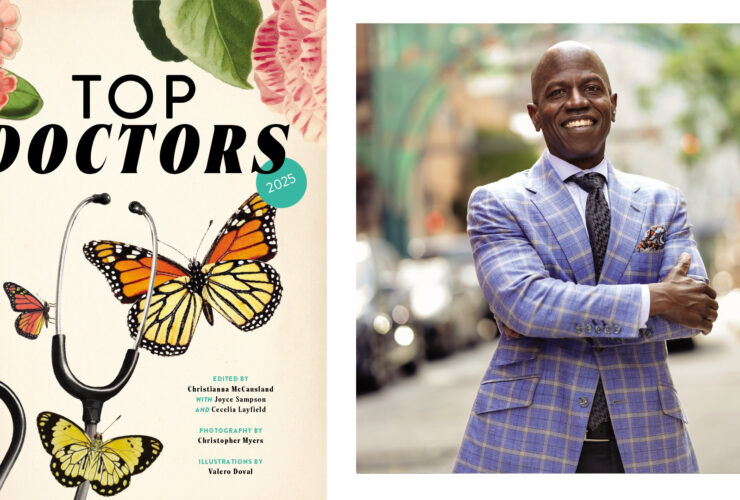

THE MODEST OFFICE at Mercy Medical Center in downtown Baltimore is filled with photos of a handsome young family and bric-a-brac-lined shelves. Its occupant arrives right on time for a morning meeting nattily dressed in a smart-fitting blue suit, complementary bow tie, and stylish glasses. Dr. Ashanti Woods is warm and gregarious, the qualities of a gifted pediatrician who understands the importance of making meaningful connections with the parents of his young patients.

Woods engages in small talk before reflecting on his journey from Baltimore City Public Schools, Howard University in Washington, D.C., a pediatric residency at the University of Maryland, and 15 years of practice at Mercy. Some of his first patients are now bringing their children in for wellness checks.

“I love kids. They’re fun and goofy, and not too serious. That fits my personality perfectly,” says Woods. “Medicine lets me serve, teach, and continually learn. Making my patients feel better or inspiring improvements in their overall well-being is what keeps me going.”

That drive is being tested by the politicizing of vaccinating school age children against infectious diseases. A poll conducted in June by the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the de Beaumont Foundation found that 79 percent of U.S. adults believe parents should be required to have their children vaccinated against preventable diseases like measles, mumps, and rubella to attend school.

The findings suggest that childhood vaccine requirements aren’t as controversial as many people believe, even as notorious vaccine skeptic Robert F. Kennedy Jr. fans the flames of skepticism as secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Most of the survey’s respondents supported mandatory childhood vaccination, regardless of political affiliation: 90 percent of Democrats, 68 percent of Republicans, and 66 percent of MAGA supporters backed the practice. Party lines also did not impact the belief that vaccines for preventable childhood diseases are safe.

Woods says the recommended vaccines approved by the CDC (and reaffirmed in a meeting of the organization in September) for school-aged children aren’t changing. At least not yet. He wonders if insurance companies—especially those that receive significant federal funding—will pay for vaccines that the CDC decides are optional.

That would leave pediatricians in a tough spot. “Do we absorb the cost of the vaccines and administer them to patients? How long could we afford to stock the doses?” says Woods. “The uncertainty creates anxiety.”

Still, he remains hopeful. “Lawmakers in both parties are starting to slow down and reconsider the public health implications before making significant changes to vaccination policies,” he says. “We’ll see how it plays out.”

A more clear and present challenge Woods deals with is that insurers are tightening the screws on reimbursement policies in relation to something called ICD-10 codes. Physicians must apply specific (oftentimes complicated) diagnostic or procedure codes to a patient’s record to receive reimbursements from some insurance companies for services provided. When improper codes are submitted, insurers deny the claims and refuse payment.

Mercy has a dedicated team to manage and resubmit denied claims, but smaller private practices often don’t have the resources, like a dedicated person, to keep up with paperwork.

“Some insurance companies are counting on that,” says Woods. “They hope enough doctors won’t notice they’re gradually losing money on improperly coded claims. It might take months before a doctor realizes why their payments have dropped for the same level or amount of care they’ve always provided. It’s a lot of red tape to navigate. Physicians need to jump through more hoops just to get the same or less pay.

“And when insurers try to save money, it often comes at the patient’s expense. That’s why attitudes toward the health care system are difficult right now.”

Patient frustration is mounting as inflationary pressures and the high cost of health care take bigger chunks out of household budgets. When Luigi Mangione gunned down the CEO of UnitedHealthcare, he was allegedly fueled by a deep hatred for the health insurance industry’s corporate greed and mistrust of the U.S. health care system. His cult following and antihero status on social media suggest some Americans share his anger.

It’s a scary time to work on hospital frontlines as potential targets of that pent-up rage. According to U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, current health care workers are five times more likely to experience workplace violence than professionals in other occupations. Consider, for example, a patient in 2022 in Tulsa, Oklahoma, who, after continuing to experience back pain after undergoing surgery to treat the issue, gunned down the orthopedic surgeon who performed the procedure. A study published last year in the Journal of General Internal Medicine reports that upwards of 64 percent of outpatient primary care clinicians experienced some form of verbal abuse.

Burley acknowledges the dangers she faces in her role and has undergone de-escalation training at Hopkins Bayview to mitigate the risks, but concerns about personal safety don’t consume her thoughts. Instead, Burley tries to cut off frustrations before they can escalate. She discusses the cost of medication with patients who’ve had to cut back on daily essentials to afford the co-pays of needed therapies. Her willingness to find treatment options that fit the circumstances of individual patients defuses some of their angst.

“That brings the conversation into a holistic perspective,” says Burley. “What is the true benefit of prescribing medications for patients who struggle to pay for basic necessities? How else can we treat their conditions?”

The Trump Administration’s cutting of federal funds earmarked for clinical research and the current political landscape has fueled a broader cultural mistrust of science and scientific experts, according to Burley, but she finds some positivity in the unintended consequences. Patients who buy into the anti-science rhetoric are more likely to research topics on their own—and discover data-driven truths for themselves along the way.

“Patients might not value the opinion of experts in the field and that is concerning,” she says. “But they’re taking more ownership in their care. Perhaps that will encourage them to be more informed about their health.”

However, that dynamic cuts both ways and could contribute to health care’s increasingly litigious landscape. Patients with unprecedented access to health care information about the care they receive might be more willing to question, rightly or wrongly, the decisions their doctors make and file malpractice lawsuits.

When Woods saw his first patient in 2007, TikTok and Instagram didn’t exist, and YouTube wasn’t what it is now. Parents couldn’t drink from the digital firehose of medical information that’s currently set to full blast.

Woods says many parents now arrive for appointments for a second opinion after consulting Dr. Google, who lists reasonable diagnoses alongside alarming outcomes. That sore throat? It could be strep, mono, or a peritonsillar abscess. It could also be throat cancer. Going down the rabbit hole of online medical information is a dangerous game for the uninformed.

“The diagnosis used to come from me,” says Woods. “Parents now have their own assumptions about what’s wrong with their kids, and that causes undo anxiety.”

It’s not that patients suddenly mistrust physicians, but they no longer see them as all-knowing demigods.

“Trust is now based more on quality relationships,” says Woods. “Physicians need to clearly explain the course of care, address the concerns patients have, and connect in a personal way. That level of commitment might mean patients won’t question a diagnosis simply because it doesn’t match something they saw online.”

Here’s an example of how things could go awry: Woods might explain to a parent that cough medicine isn’t recommended for children younger than six years old because the part of the brain that controls the cough reflex isn’t fully developed and the risk of side effects includes drowsiness and dizziness.

Parents who don’t heed his warning might administer additional doses in a pointless attempt to stop the coughing, increasing the risk of potentially dangerous side effects without relieving the symptoms. Physicians who don’t protect themselves through detailed medical documentation open themselves up to getting sued for malpractice.

Every physician knows that if it’s not documented, it’s not done, and meticulous documentation is now more important than ever. But documentation takes a tremendous amount of time, as much as six hours a day for an ambulatory physician according to the American Medical Association (AMA). That’s why, with permission, Woods uses an AI program that records the conversations he has with parents and automatically populates the transcripts into patient charts. It’s efficient—and ensures he covers himself.

“Yes, we’re thinking about the legal side of patient care all the time,” he says. “That’s the reality of the current climate. Thankfully, nothing serious has happened and we want to keep it that way.”

MEDICAL STUDENTS ARE DRIVEN and meticulous perfectionists, important traits for succeeding in medicine. “They’re also more likely to suffer anxiety and experience imposter syndrome that comes from constantly comparing themselves to others,” says Dr. Nicol Tugarinov, who was named the 2024 Student of the Year at the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM). “Being surrounded by such high achievers makes those feelings nearly inevitable.”

Persistent self-doubt in this setting can lead to devastating consequences. Medical students are three times likelier to die by suicide than their contemporaries in the general population, according to a 2019 study by the AMA.

Tugarinov, who is currently in the internal medicine residency program at Penn Medicine, is a self-described Type A personality and admits to fighting through bouts of anxiousness. She’s always been intentional about finding ways to keep herself regulated when stress levels rise.

That self-awareness first drew her to UMSOM’s Wellness Committee, a multi-departmental effort to champion student well-being. Tugarinov became a representative for her class during all four years of medical school and worked with other wellness reps, student affairs faculty, the student counseling center, and the leaders at the school’s fitness center.

Those connections led Tugarinov to spearhead the launch of the Peer Support Network in August 2023. The program pairs med students with peers who are trained in active listening and suicide prevention, and who can provide support, camaraderie, and connections to professional and personal resources when needed. It’s an incredibly valuable program, both for the students who receive support and those serving as mentors.

“Medical school can feel extremely isolating, especially in the third year,” she says. “The first two years involve didactic teaching, and you see classmates every day. But once clinical rotations begin, everyone is scattered across different teams and hospitals. It’s easy to feel like you’re working in your own silo. Sometimes you just need to talk to someone who understands what you’re going through.”

Depression, anxiety, and mental strain come with advanced education, but, “Med students are less likely to admit they need counseling but are actually the ones who would benefit from counseling services the most,” says Tugarinov.

“Everyone who goes into medicine is a bit idealistic,” she continues. “So much of our energy is focused on getting into medical school that it’s easy to ignore the hard realities of the profession. But the challenges eventually become impossible to overlook. You start to see the difficulty of the work ahead and the toll it can take. I knew about burnout before medical school, but I didn’t feel the weight of it until I experienced the pressures myself.”

It’s not just new physicians who feel this mental toll. In the most recent national burnout survey of more than 7,600 U.S. physicians published in the July issue of Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 45 percent reported at least one symptom of burnout: emotional exhaustion, detachment from work, depersonalization, and unfeeling toward patients.

That’s down from an alarmingly high rate of 62 percent in 2021, but AMA President Dr. Bruce A. Scott believes burnout levels remain too high and calls for continued efforts to fight the root causes of the physician burnout crisis.

Notably, female physicians are 27 percent more likely than male physicians to suffer burnout, and internal medicine doctors are among the practitioners with the highest risk.

Burley checks both boxes. She says many physicians grow frustrated with the bureaucracy they face when trying to do what’s best for their patients. Every form, insurance approval, or task that pulls them away from the practice of medicine contributes to the mental strain.

“There’s so much work required just to move care forward—dealing with insurance barriers or systemic issues in the health care system—that it can feel like you barely have time to be with patients,” she adds.

Technology, especially AI, is already beginning to reshape medicine in ways that could ease some of the daily burdens that fuel burnout. AI tools like the one Woods uses could extract key information from clinical documents to generate accurate patient notes, saving physicians countless hours each week.

The same goes for other time-consuming tasks like prior authorizations, which currently require endless calls to insurance companies to secure approval for essential medications. Automating or streamlining those processes would allow doctors to spend less energy fighting administrative battles and more time focusing on why they got into the profession in the first place.

“Many physicians who suffer burnout talk about moral injury, the seemingly endless amounts of small tasks that take them away from practicing medicine,” says Tugarinov. “Hopefully, technological advances will remove some of the administrative burden from physicians so they can focus more on patient care.”

Medicine was always hard. Grueling training. Weekend shifts. Early mornings. Late nights. Prioritizing the care of patients over everything else. Personal sacrifice is part of the deal.

So why do it?

Woods considers the question, leans forward and recalls walking from Mercy to M&T Stadium the previous day to meet his friend for a Ravens preseason game. Outside the main gates, he ran into a young patient he’d seen in clinic hours before.

“He introduced me to his friends as ‘my doctor,’ and they all thought that was so cool,” says Woods. “I love being able to encourage and influence kids. I’m still excited about caring for patients and being part of families across generations. It’s truly amazing to have that kind of impact on people’s lives.”

A baby cries in a nearby exam room. Woods smiles and excuses himself. His next opportunity awaits.