Health & Wellness

Top Doctors 2019

Johns Hopkins emergency surgery chief Joseph Sakran, who was shot in the throat as a teenager, has become a leading gun-violence prevention advocate.

“DO YOU MIND IF I PUT ON SOME MUSIC?”

says Dr. Joseph Sakran, the 42-year-old director of emergency general surgery at The Johns Hopkins Hospital, while staring at the screen of his office computer and clicking through a Pandora channel featuring country songs. Sakran asks if I’ve heard the new Zac Brown Band tune yet. “It’s so good,” he says, telling his computer to play “Leaving Love Behind.” A few lines sound as if they were written just for him, especially this one: “. . . and I missed my shot at dying young, a long time ago.”

We’re on the sixth floor of one of the hospital’s state-of-the-art towers in East Baltimore, and Sakran is just beginning a 24-hour on-call shift as late afternoon light angles through a small window behind him. Sporting standard blue operating room scrubs and a black goatee and glasses on a round face befitting a former high school offensive lineman, Sakran, one of the hospital’s top trauma surgeons, is being his usual polite and affable self in asking for permission. Spend a few minutes with him and you learn he’s the type who says hello to everyone he walks past in the hallway.

“It’s just how I was raised,” says Sakran, the son of a pair of hardworking Middle Eastern immigrants. He is also, according to those who work alongside him, the rare colleague who is completely approachable and as comfortable talking about last night’s television dramas with the office assistants (one favorite is The Wire-ish crime show Snowfall on FX) as he is commanding one of the nation’s busiest and bloodiest trauma bays. “It doesn’t matter how stressful that room is, how bad the situation is,” says Dr. Ryan Fransman, 31, a chief trauma surgery resident who trains under Sakran at Johns Hopkins, “you always feel like he’s in control.”

Today will mark a rare relatively calm shift, by trauma surgery standards. His pager is quiet. No need to put on his scrub cap and head to the emergency room. Primarily, he’ll work on a pair of consults on two patients, one a quadriplegic man who might need a feeding tube and another man who has a bleeding ulcer somewhere in his intestines. (When discussing the latter case with a resident, Sakran quickly sketches the human digestive tract with a black ballpoint pen on a piece of printer paper, noting the jejunum and duodenum. “That’s where the money might be,” he says.)

But on other days, his job means operating under the most intense circumstances, like he did earlier this year, on a man who had been rushed to the E.R. after being shot more than a dozen times. He had injuries in every cavity of his body, and Sakran needed to perform a complex surgery called a clamshell thoracotomy, essentially opening up the man’s entire chest with a scalpel and scissors (and sometimes a saw to break the sternum) to begin life-saving repairs around the heart and lungs. “You rarely live from the type of injuries that he had,” Sakran says, but this man did.

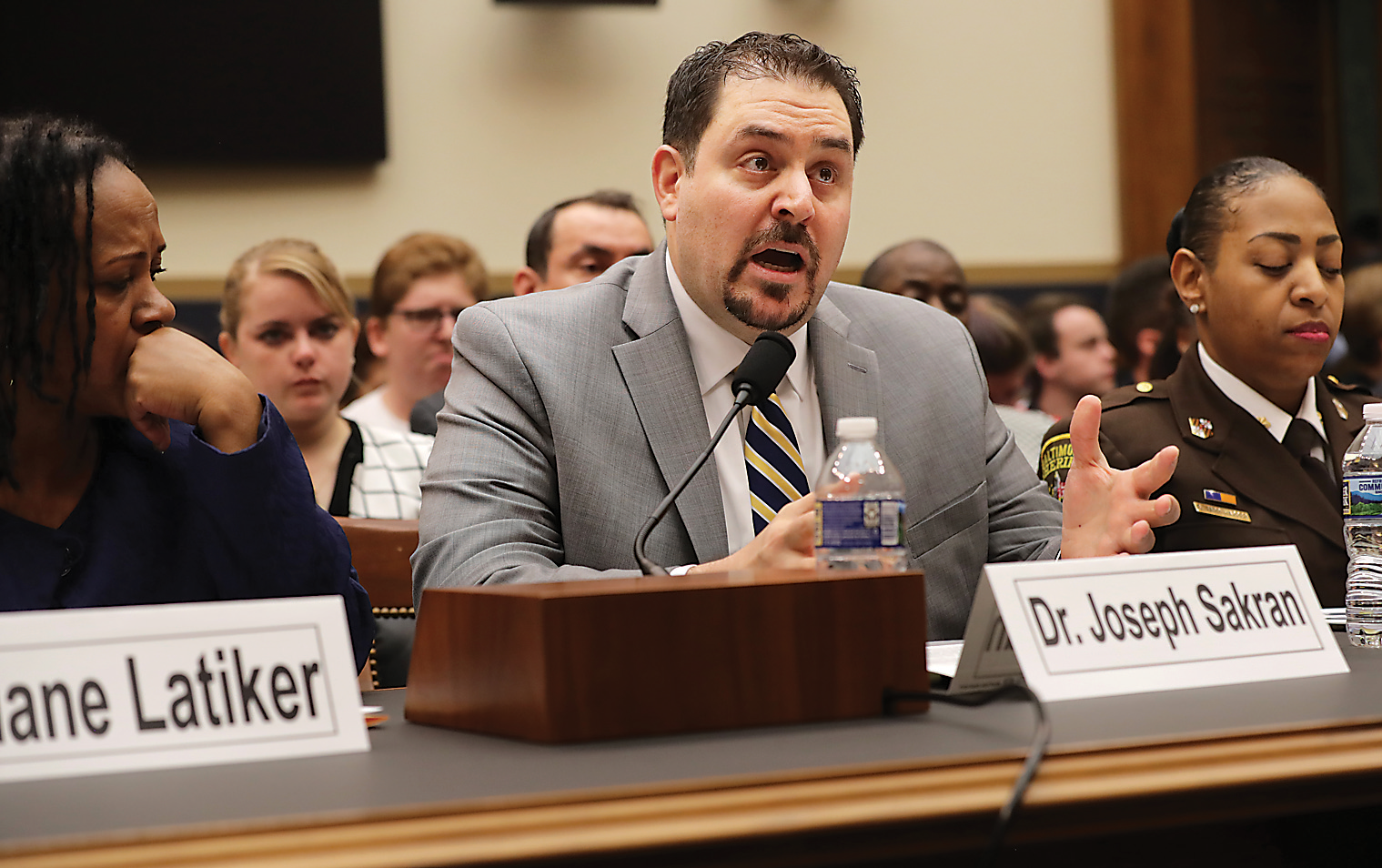

“I’ve said it so many times,” Sakran continues, “the worst part of my job is having to go talk to the families of those loved ones and tell them that the child that left that morning is never coming home again.” He’s done it too often, hundreds of times, which is why he’s currently in the middle of moving to Washington, D.C., a temporary relocation from his home in Brewers Hill, for a yearlong sabbatical as a health policy fellow at the National Academy of Medicine. Sakran, who founded the group Docs Demand Action after the mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida last year, has twice testified before Congress on gun-violence prevention issues while increasingly appearing on cable news shows as a passionate, articulate gun-violence prevention advocate. It’s a role he’s uniquely qualified to fill, not just because of the nature of his life-saving profession, but his own life-and-death brush with gun violence as a teenager.

As a high school senior, Sakran was shot in the throat when a fight broke out after a high school football game in his native Burke, Virginia. He was merely an innocent bystander—it was as wrong place, wrong time as you can get. The bullet from a .38-caliber handgun, fired into a crowd, entered the right side of his neck, hit one of the carotid arteries carrying blood to his brain, and ruptured his trachea before stopping in his shoulder. The near-death experience, and the doctors who saved his life during hours of surgery, motivated him to pursue a career as a trauma surgeon. And he’s done that for the past seven years, becoming a leader in his high-pressure field, spending the last four years operating and training the next generation of trauma surgeons at the world-renowned hospital in Baltimore that, tragically, receives several hundred gunshot victims each year. When Sakran speaks—sometimes projecting can be difficult since he has one working vocal cord; he lost use of the other in the shooting—or tweets, which he does a lot, he does so with authority about gun violence in America, one of our most intractable, politicized problems.

“He didn’t go to med school to do this [become a gun-violence prevention advocate]. This wasn’t part of his plan,” says Bellal Joseph, Sakran’s close friend, a fellow gun-violence prevention advocate and the chief of trauma, acute care, burn, and emergency surgery at the University of Arizona. “It’s just when you suffer and struggle and you tell your story, it’s very different than those people who make rules without ever being on one side of the fence. He’s been on both sides. He has the merit—he’s not just a talker.”

When the National Rifle Association tweeted and mocked “self-important anti-gun doctors” last November, telling them to “stay in their lane,” it was Sakran’s visceral reply—“We take care of these patients every day. Where are you when I’m having to tell all those families their loved one has died”—that went viral and started the hashtag and Twitter handle @ThisIsOurLane. Doctors around the country began posting pictures of blood-covered scrubs or operating room floors, and Sakran landed on CNN and MSNBC’s guest lists.

Through August in Baltimore alone, 700-plus people have been shot and 227 have died from gun violence. Bullets fly with similar frequency in cities like Chicago and Philadelphia, where Sakran worked for two years at Penn’s trauma clinic. “Young black men are being killed on our streets,” he points out in particular. Nationwide, more than 350,000 people have been killed by firearms over the past decade, but most of the stories don’t make headlines.

“This is a public health crisis we’re facing,” Sakran says. “And we have an obligation to tell the stories, especially those of us that are on the front lines seeing this day to day.”

So, in what can be described as a culmination of his journey to this point—and why he’s moving from his Brewers Hill bachelor pad and looking to rent his place—Sakran is going to Washington for the opportunity to sit alongside policymakers on Capitol Hill. As the embodiment of two sides of the gun debate, survivor and doctor, he hopes to deliver his rallying cry where it will have the greatest impact. “I just try to do my part,” he says.

After Sakran was shot, as friends tried to lay him down on a curb to help and see where he’d been hit, he began choking on his own blood. It was squirting from his windpipe and soaking his white shirt and pants. Paramedics took him by ambulance to Inova Fairfax Hospital, where he was born, and now struggled to remain alive. He remembers the residents and an E.R. doctor briefly arguing over what to do before the on-call trauma surgeon arrived on the scene. That trauma surgeon acted quickly, unlocking the gurney Sakran laid on and wheeling him into the operating room. “I have to do this to save your life,” the doctor had told him, and he performed what Sakran now knows is a regular procedure in a trauma room: an emergency tracheostomy to provide him a secure airway. Another doctor then graphed a vein from Sakran’s leg to the vital artery in his neck.

“I could have been dead,” he says now, 25 years later. “I could have been paralyzed. I could have stroked.”

He woke up close to noon the next day in the intensive care unit, on a ventilator, with a tracheostomy tube in his throat that would stay in place for six months. Yet, in typical teenage fashion, Sakran was primarily worried about missing what was supposed to be the first day of his first job at a local pet store. And that his parents would find the cigarettes he had on him when he was shot.

“He was never a bad kid,” says his brother Mark, a child and adolescent psychiatrist, “but he was also a kid who probably wasn’t on the path to becoming a trauma surgeon. He wasn’t the most compliant of children. But after he was shot, life truly stopped. We all had this moment of pause, and we all grew up really quickly.”

It took several months and multiple additional surgeries to remove scar tissue in his neck before Sakran began to comprehend and reflect on what happened. One night, Sakran’s father, an aerodynamic space engineer who immigrated from Israel with his wife 40 years ago, caught his son looking in the mirror at his wounds.

“Listen,” he says his father told him, “you can feel sorry for yourself, or you can take this as a second opportunity and make a difference for other people.”

The boy who’d been shot decided to find the doctors at the hospital who saved his life. They were trauma surgeon Dr. Robert Ahmed and vascular surgeon Dr. Dipankar Mukherjee, and Sakran asked to shadow them.

“That moment really changed me for the rest of my life,” he says, and he embarked on an almost obsessive quest to “make a difference.”

Sakran trained to become a medic and a firefighter at the City of Fairfax Fire Department while attending college at George Mason University and applied to med school. After graduating from Israel’s Ben-Gurion University in 2005, he returned again to the emergency room at Inova Fairfax Hospital for residency. He went through intense training next to his own doctors, an inspiring and nerve-wracking experience. “You felt like you had to be the best version of yourself possible,” Sakran says. “I had to show them what they did was definitely worth it and make them proud of this second opportunity they’ve given me.”

It wasn’t long before Sakran performed the identical emergency surgery he once needed from them. And he’s done it many times since in operating rooms in Virginia, Philadelphia, and here.

“To take care of a patient that’s been shot in the throat? It’s pretty crazy,” he says, pausing at the thought and staring down at the top of his desk. “Some have survived, some are paralyzed, some are dead. It makes you think about how lucky you are.”

The statistics are staggering in Baltimore, of course, and it can sometimes feel as if many people have become accustomed to, or feel helpless against, the overwhelming number of those shot and killed by guns every year, as if it’s an unsolvable issue. “We are purely in a reactive mode at the moment,” says Fransman, the Hopkins chief trauma surgery resident, in terms of dealing with the ongoing crisis. On the day we spoke, he said six people had died in the emergency room that week, all from gunshots.

Overall, more than 40,000 people died by guns in 2017, the deadliest year for gun violence on record in the U.S. Since the beginning of 2019 through late September, guns have killed more than 11,000 and injured 22,000 people, according to the Gun Violence Archive, a nonprofit organization that tracks incidents. Most gun deaths are from suicides, followed by homicides and accidental deaths. Meanwhile, every time a mass shooting grabs the national consciousness, gun safety advocates rally for change, but little or nothing happens in Congress, even though recent polling suggests most Americans support stricter access to guns. Sakran recognizes that, because of his story, he might be someone who can help get effective legislation through Capitol Hill’s political quagmire.

Holistically, gun-violence prevention is a complex problem that requires multiple nuanced approaches, Sakran believes. For example, he rejects President Trump’s assertion that mental health is the biggest contributor to mass shootings. “Less than five percent of violent crimes are committed by someone with a mental health disorder diagnosis,” Sakran notes.

But, of course, Sakran acknowledges, better mental-health policies are a critical part of the discussion for preventing suicides.

Some key policy changes Sakran wants to see: Universal background checks; extreme risk protection orders, also known as “Red Flag” laws, that allow law enforcement, after a due process, to take guns from people who are found to be a danger to themselves or others; and more federal funding for gun violence research. “One out of five firearms are acquired through means where the person doesn’t have to undergo a background check, like a gun show or on the internet,” he says. That last policy change is critical to Sakran as well. The Dickey Amendment, passed in 1996 with lobbying from the NRA, states that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention can’t promote or advocate for gun control. The amendment cut gun research funding by 90 percent, essentially taking it out of the public discourse (this after a CDC study concluded that having a gun in the home was more dangerous than not having one).

Public support for more gun-violence prevention measures continues to grow, according to polls. Those numbers don’t seem to be translating into meaningful legislation, however, at least not fast enough for Sakran’s liking. In February, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a pair of bipartisan bills, HR-8, and HR-1112, that would strengthen background checks for gun buyers, but as of press time they have yet to be voted on in the Republican-controlled Senate. Sakran was then asked to be part of a group of experts who testified before Congress in early September, urging the legislation to be considered as soon as possible.

“Over one million Americans will be shot in the next decade,” Sakran said, wagging his finger at the House committee, trying to make sure he was heard, in a clip CBS Evening News would play a few hours later. “We are the ones that understand all too often that the best medical treatment for this crisis is often prevention.”

It’s not about taking away guns, he says later. “It’s about allowing people to have the freedom of owning, but with responsibility. Our elected officials just need to have the moral courage to do the right thing. And we, as citizens, need to hold them accountable.”

He just doesn’t want to do the toughest part of his job any more, he explains. He doesn’t want to tell a family, a mother, father, sister, brother, that their loved one is dead. That there was nothing they could do.

Sometimes, Sakran continues, he catches himself looking through the waiting room glass before delivering the news. He thinks about how his parents must have felt when Dr. Ahmed came to talk to them all those years ago. And he thinks about the 17-year-old version of himself who lived through the trauma and survived.

“It never gets easy,” he says of breaking the tragic news to the families of victims of gun violence. “It’s heart-wrenching to watch that anguish, to listen to those screams.”