Health & Wellness

Top Nurses 2019

Our fifth annual awards program salutes the front line of modern health care.

In modern health care, the spotlight is too often on the doctors. That was understandable a generation or two ago, maybe, but things have changed. Now nurses are at least as likely as physicians to be the ones attending to patients, and those with specialized training not only can perform many of the same roles as a physician, but are the backbone of health care today.

You’d be hard-pressed to find a region with more great nurses than metro Baltimore, and our job in Baltimore’s fifth annual Excellence in Nursing survey was to identify the best of the best.

To arrive at the results, the unveiling of which coincides with National Nurses Week in May, we solicited nominations from peers, supervisors, and patients of registered nurses—both in and out of hospitals—who represent the nest in their fields, and we received an overwhelming response. And in our accompanying story, “Nursing’s Next Generation,” we look at the extra effort local hospitals are making to attract and train new recruits amid a looming shortage of R.N.s.

There were 18 nursing specialties for which we accepted nominations in a process that took nine months. Then the hard part began: picking the finalists. For that, we relied on an impressive panel of highly experienced R.N. advisors, who divvied up the specialties and pored over the hundreds of nominations to arrive at our winners.

Nursing’s Next Generation

Baltimore is uniquely poised to address the looming nursing shortage.

By Rebecca Kirkman

Tamika Missouri

Maternal Child Health, Mercy Medical Center

Ever since she was a child, Carrie Moyer was a fan of nurses, whether they were easing her fears during routine doctors’ office visits or caring for ailing family members. “I always loved them,” she recalls. “Becoming a nurse was always in the back of my mind.”

Now, as a 31-year-old first-year oncology nurse at Mercy Medical Center in Baltimore, Moyer has finally fulfilled that dream. But the Locust Point resident took the longer road to get there.

“Nursing is actually a second career for me,” says Moyer, who graduated from the University of Georgia in 2009 and worked in public relations at an Atlanta children’s hospital. “I really loved working there, but, after a couple of years, I realized the reason I loved it was because of the patients. I started thinking, maybe in the long term, I should consider going back to school.”

So when Moyer and her husband, Glenn, a Navy officer, moved to Annapolis in 2015, she enrolled in the University of Maryland School of Nursing’s (UMSON) Clinical Nurse Leader program, which offers an entry-into-practice master’s of science in nursing for those who already hold bachelor’s degrees in other disciplines.

And people like Moyer are getting into nursing at a critical time: There’s a wave of R.N. retirements underway, and a real shortage of new recruits to fill the gap, in part because there isn’t enough capacity in nursing schools to meet the new demand. So the health care community is getting creative to try to triage the problem.

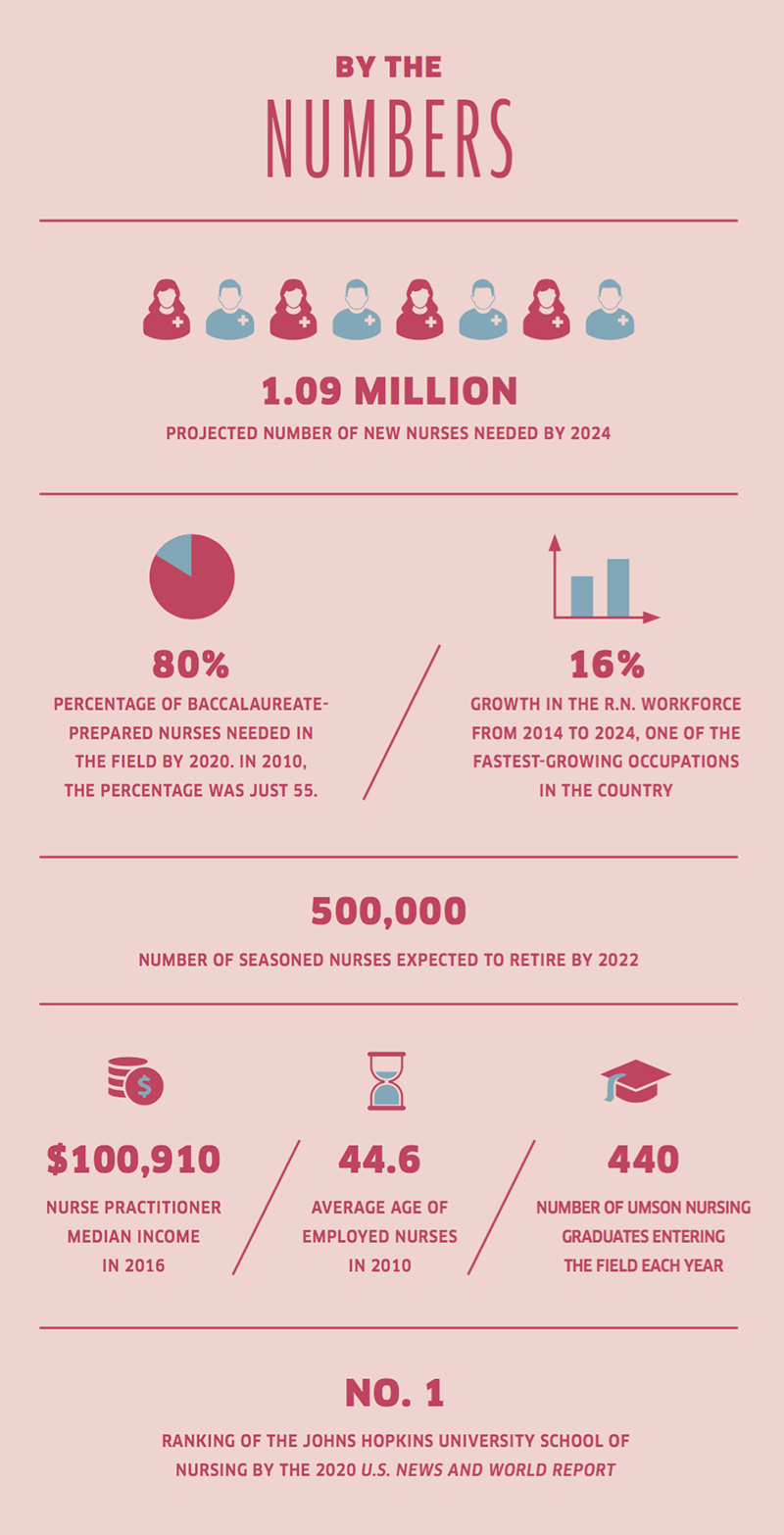

The UMSON Clinical Nurse Leader program, ranked second in the nation by U.S. News & World Report, is part of a growing number of programs designed to address the shortage of nurses nationwide: The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects the need for an additional 1.09 million nurses to enter the field by 2024.

“We’re one of the professions in which the demand continues to grow—by a projected 16 percent in the next five years,” says Jane M. Kirschling, dean of the UMSON. “And we also know we have to replace the nurses that retire. So the combination of the growth and the replacement of the baby boomers as they finally leave the workforce just creates this unbelievable demand for well-educated nurses.”

Aline Dagdag

Psychiatry, University of Maryland Medical Center

Not only are baby boomers leaving the workforce, but they’re likely to soon become patients, and that huge demographic bubble means greater demands on the health care system, says Judith A. Fuestle, associate dean of nursing at Stevenson University. “We’ll have fewer nurses and a population with more health care needs. We need to increase our number of students.”

Not too long ago, health care facilities looked further afield to fill the nursing void: Fifteen years ago, it was common for U.S. hospitals to hire foreign-trained nurses, often people who had earned their nursing degrees in the Philippines or India, according to the National Council of State Boards of Nursing. But it was a controversial practice, as critics worried about brain drains from developing countries and were concerned that the foreign-trained nurses might be exploited by U.S. employers.

Since then, the number of new foreign-trained nurses in the U.S. has fallen by half, from 10,636 in 2004 to 5,696 in 2017. Three factors have driven that number down: First, during the 2008 recession, there was an unexpected and prolonged boom in U.S. nursing-school enrollment. Second, in 2009, the U.S. cancelled the H1C visa program, which was aimed specifically at foreign nurses. Finally, in 2010, the World Health Organization enacted a new Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel, which discourages hiring nurses away from certain low-income countries.

In any case, the problem is no longer a shortage of interested applicants. Ample employment prospects and good wages have made the nursing profession attractive again. At the same time, however, there’s a bottleneck: Schools across the nation continue to turn away qualified applicants due to limited space. The University of Maryland School of Nursing, for instance, turns away nearly as many students as it accepts for that reason, says Kirschling.

Recruiting faculty is another challenge, she adds, noting that advanced-practice nurses are compensated better on the health care front lines than in higher education.

Despite these challenges, the greater Baltimore region’s wealth of highly ranked universities and hospitals gives it a unique edge over other metro areas to tackle the problem.

The recent 2020 U.S. News & World Report’s “America’s Best Graduate Schools” named The Johns Hopkins University the top master’s nursing school in the nation, and its online program and doctorate of nursing practice also ranked No. 1. University of Maryland School of Nursing’s master’s-level nursing informatics program was ranked No. 1 in the nation, while five additional nursing programs ranked in the top 10.

Those sorts of reputations are helping local universities contribute to a pool of highly trained local talent. Across the University of Maryland School of Nursing’s Baltimore and Shady Grove campuses, for example, “we’re putting somewhere between 400 and 440 new graduates into the market each year,” says Kirschling. “And the overwhelming majority stay in Maryland.”

To reach more students, the school is partnering with 13 regional community colleges to offer dual admissions, helping students streamline the path to baccalaureate degrees, a growing necessity for entry-level jobs in the area.

Daniel Neas

Vascular Surgery, Saint Agnes Hospital

Rebecca Landreth

Patient Care Manager, Behavioral Health MedStar Franklin Square Medical Center

Additionally, Maryland is home to the state-funded Nurse Support Program, run by the Health Services Cost Review Commission and the Maryland Higher Education Commission to bolster the number of nurses entering Maryland hospitals and pursuing graduate education by providing grants to hospitals and higher education institutions.

New technology is at work, too, in the drive to train more R.N.s. For example, nursing students at Stevenson University regularly encounter the same patient, Victoria. Housed in the Sandra R. Berman School of Nursing and Health Professions, Victoria is a lifelike, high-fidelity labor and delivery mannequin—she’s basically a robot—controlled by computer software that simulates a patient in a hospital setting.

Jennifer Spahn

Clinical Program Manager, Nurse Residency Program Greater Baltimore Medical Center

“They blink, they bleed, they talk—everybody in nursing education has been using simulation for years now,” explains Feustle, stressing that simulation can never replace real-world clinical experience.

Working with mannequins, however, allows faculty to guarantee students will encounter certain health care situations in the classroom setting. Or, as Feustle says, “Victoria always delivers.”

Thanks to this new technology, the university has been able to add 30 students to its fall class.

But there will never be a substitute for mentoring and other forms of personal interaction: “In the hospital, there’s going to be other experienced nurses who can help mentor the new graduates coming out,” says Feustle.

Mentoring is an important part of the system at many hospitals, including Mercy Medical Center in downtown Baltimore, where it can also be a recruitment tool.

“The students may want to pick my brain about nurse residency [possible future employment by the hospital] and how they should prepare, or if they have an interest in a particular clinical topic,” says Monica Nelson, Mercy Medical Center’s professional development specialist. “We have expertise so that we can have a conversation with them. While they’re here, that’s when we want to grab them.”

It seems to have worked on Carrie Moyer: When she was interviewing for nursing jobs, she made a point to ask about what support systems were available to new nurses. “I had seen how nursing can be a really rewarding career, but also challenging. I wanted to go somewhere that would set me up to succeed, not just throw me into the deep end,” Moyer says. “That was something appealing to me when I interviewed at Mercy.”

She also knows she can take her skills anywhere: “We hope we’ll be in the Baltimore area for a couple more years, but eventually we’ll be moving, and we felt there would be opportunities for me wherever we went. Plus, nursing is flexible—I could work full-time, part-time, become a school nurse, and be able to work once I do have children.”

It may have taken her awhile to become a nurse, but she knows it’s exactly where she belongs.

Sol Dominic Sebastian

Critical Care RN II, Sinai Hospital of Baltimore

Tammy Jones

Charge Nurse Neuroscience, Johns Hopkins Bayview