History & Politics

From Fells to Free

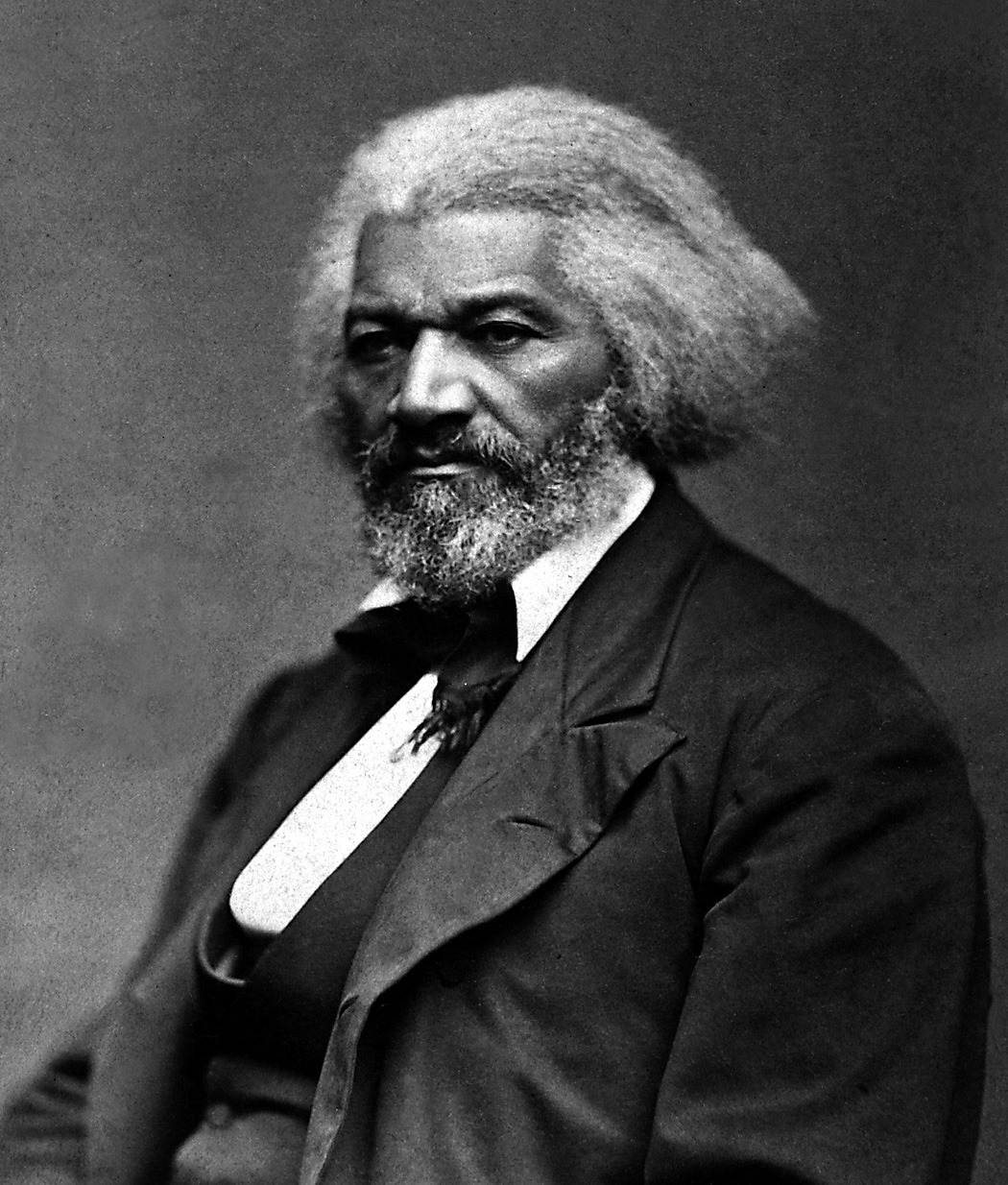

Celebrating Frederick Douglass’ 206th Birthday.

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey did not know the year or date he was born. He said in the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass that he did not remember ever meeting a slave “who could tell of his birthday.”

Born on a Talbot County plantation, he was 7 or 8 years old when he was sent to live in Fells Point and work for Hugh Auld, brother to his master’s son-in-law. He later chose Valentine’s Day to celebrate his birthday, recalling his mother had referred to him as her “Little Valentine.” The year of his birth had been recorded as 1818, marking February 14 this month as his 206th birthday.

The future writer and abolitionist also selected (for his safety) his own surname as a young man, following his escape from slavery in Baltimore. At the suggestion of a Black couple who had helped him and his wife make their way to Massachusetts, he choose Douglass after an exiled knight in Sir Walter Scott’s poem Lady of the Lake. Despite his newly won freedom, new surname, and new birthday, Douglass nevertheless refused to forget the vicious apartheid system he had been born into. He had not parted with his first name, he said, “to preserve a sense of my identity.”

For decades after his death in 1895, “Douglass Day” birthday events were celebrated in Black communities. One of the last national events honoring Douglass was the release of a U.S. Postal Service stamp bearing his fiercely dignified visage in 1967, the year before the sesquicentennial of his birth. In Baltimore, local historian Lou Fields has almost singlehandedly kept Douglass’ spirit alive, hosting “Path to Freedom” walking tours in Fells Point for the past 18 years.

“He was born into slavery, grew up watching slave ships dock all around Fells Point, and witnessed slaves being marched in shackles to auction in the market square,” says Fields. “We are still talking about his legacy two centuries later because he became one of the great freedom fighters.”

In Baltimore, the young Frederick secretly learned to read after an introduction to the alphabet by his new master’s wife. He later worked in servitude as a ship’s caulker in Fells Point, and then, as a 20 year old, he escaped on a train to Philadelphia, posing as a free Black sailor and carrying fake documents.

Once free, Douglass became one of the great prophets of universal human rights. In his 1845 memoir (the 5,000-copy first run sold out in four months and became one of the most important works of anti-slavery literature), he recounted the extreme cold and hunger he had suffered as a child on the Eastern Shore, where he was kept nearly naked with no shoes or bed. He also recalled witnessing his aunt getting whipped until blood poured from her back, and his own whippings. Two years later, Douglass launched The North Star, an influential Rochester, New York, newspaper whose rallying cry was “Right is of no Sex—Truth is of no Color—God is the Father of us all, and we are all Brethren.” Finding inspiration and a reason to love his country in the Declaration of Independence, he agitated for abolition, desegregation, public education, and women’s suffrage.

During the Civil War, Douglass met with President Abraham Lincoln in Washington to protest the disparate treatment of Black soldiers in the Union Army. After initially considering Lincoln not a militant enough abolitionist, the two became friends. Following the Civil War, Douglass was named to several political posts himself, serving as president of the Freedman’s Savings Bank, chief of affairs to the Dominican Republic, and later ambassador to Haiti. He was also named the second president of the Colored National Labor Union and was the first African American nominated for vice president, selected—albeit without his approval—for the Equal Rights Party ticket.

Douglass returned to Baltimore many times, serving on the board of the Black-owned Chesapeake Marine Railway & Dry Dock Company in Fells Point and building five rental homes for Blacks on South Dallas Street. (In 2003, those homes, which still stand today, were listed in the National Registry of Historic Places.) At the old Frederick Douglass High School, Baltimore’s original “colored” high school, he gave the commencement address in 1894.

“I am a Marylander and love Maryland and her people,” Douglass was quoted in The Sun in 1891. “I feel much. . . . affection for this old spot around Fells Point where I first felt that I might be useful in advancing and elevating my race.”

STORIED sTREETS

Follow Frederick Douglass’ footsteps across eight area sites related to the iconic abolitionist’s Fells Point past.

BY LYDIA WOOLEVER

The Fells Point wharves stood in the center of the Baltimore slave trade, with ships waiting along the neighborhood’s harbor to carry slaves to auction in southern ports.

As a child, Douglass was sent to this block, then known as “Happy Alley,” to serve the family of Hugh Auld, where his wife, Sophia, taught the young boy the alphabet.

At a shop at 28 Thames, now the Thames Street Oyster House, Douglass acquired The Columbian Orator, a collection of poems and essays—and the first book he ever owned.

As a young man, Douglass worked at the local shipyards, where he became a skilled caulker and builder.

When Douglass escaped slavery in 1838, he was thought to have passed through this then-train station, now the Baltimore Civil War Museum, on his path along the Underground Railroad.

Toward the end of his life, in 1892, Douglass purchased land on Dallas Street and built five homes to be used as rental properties for African Americans. He also attended church nearby on what was then known as “Strawberry Alley.”

On the western edge of Thames Street, this national heritage site celebrates Douglass’ time as a young man in Baltimore shipyards, as well as Isaac Myers, who there co-founded America’s first Black-owned shipyard, the Chesapeake Marine Railway and Dry Dock Company.

At the entrance to the maritime park, there sits a six-foot-tall bronze sculpture of Douglass, created by Maryland Institute College of Art graduate Marc Andre Robinson.