News & Community

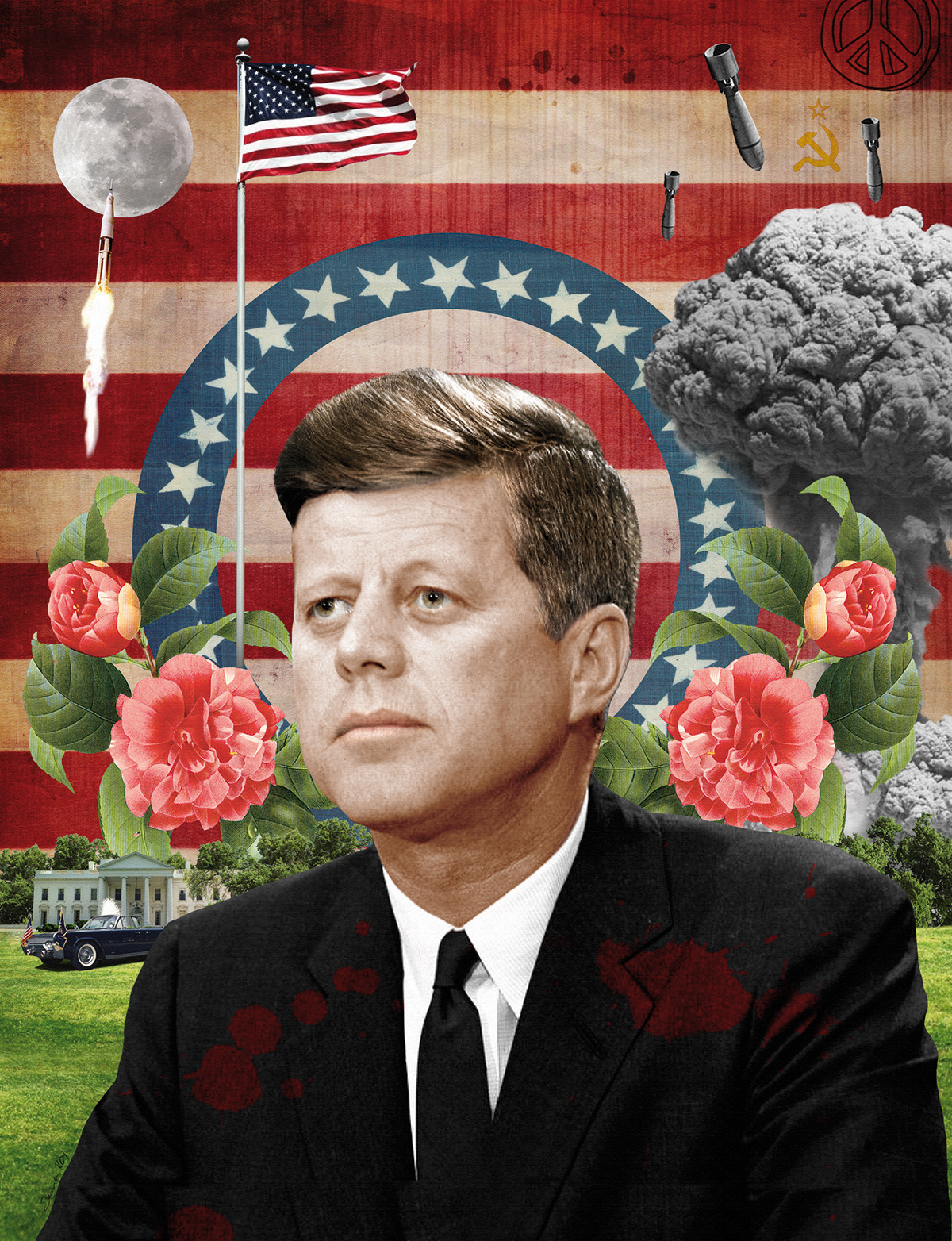

JFK: 50 Year Anniversary

Baltimoreans reflect on the significance of John F. Kennedy's assassination and how it resonates a half century later.

Gus Russo

Investigative journalist, 64, co-editor of Where Where You? America Remembers the JFK Assassination

Trying to explain the impact of JFK’s death to a generation that

lives in the micro-moment, eschewing history books in favor of cosplay

and Grand Theft Auto V, borders on the impossible. But for the tiny

minority that recognizes the study of history as the best means to

understand our present and future, I’ll throw in my two cents.

To fully comprehend how the bloody events of November 22-24, 1963

(three dead, one wounded, 189 million traumatized) metaphorically

wounded a generation, one must seek perspective. The world before JFK

was drenched in grays: gray-haired presidents who resembled retired

corporate execs; the eerie, grayish light emanating from ubiquitous

black-and-white TV sets; and the darkening gray clouds of the nascent

civil-rights movement. But by 1961, the year of Kennedy’s inauguration,

color television consoles from Sears & Roebuck and Montgomery Ward

were finally affordable and saturating the country’s living rooms—just

in time, it turned out, for the first presidential inauguration

broadcast in color.

It was a fitting synchronicity that bordered on the surreal, for on

Friday, January 20, 1961, we watched as America’s first young,

movie-star president (43 years old, the youngest elected in history) and

his movie-star leading lady (31 years old) were ushered into the

nation’s house previously occupied by Dwight D. Eisenhower (70) and his

wife Mamie (64). Jack’s golden tan, coupled with Jackie’s near-porcelain

beauty were nothing short of breathtaking.

In today’s terms, it would be like Brad and Angelina succeeding George H. W. Bush and his pearl-necklace-wearing wife Barbara.

Amazingly, another synchronicity was also taking place: the post-war

baby boom generation was now old enough to have some money in its

collective pockets. We were arguably the first American teenagers that

could choose a college education (or to just meander) over entering the

workforce. We had numbers, power, and a sense of adventure unavailable

and unthinkable to our wartime parents. And now we had our young First

Family to lead the way into this new frontier, JFK doing it with a

wicked sense of humor to boot. (He kept the Fourth Estate in stitches at

his frequent press conferences; they were in the palm of his hands. Had

this ever happened before?) It was a confluence of events to beat them

all, and it seemed—for white America at least—like it was time to have

big fun. JFK did it with the Rat Pack, and we teens did it with rock and

roll. We were even going to go to the moon! Hang on for the joy ride.

With light speed we were projected into what seemed like a new and

exhilarating universe. A few years later, John Lennon wrote a song

titled “Sun King,” which he said came to him in a dream: “Here comes the

Sun King. Everybody’s laughing. Everybody’s happy.” For many of us, JFK

was the Sun King. It seemed too good to be true, and, of course, it

was: JFK’s golden glow was, in fact, the byproduct of Addison’s disease;

his sense of fun extended to humiliating his wife on a daily basis; and

his missile crisis heroics were merely resolving a crisis he created

with a disastrous Cuba policy—the missiles of October were placed in

Cuba by the Ruskies to prevent a second unprovoked, Kennedy-backed

invasion of the small island.

But we didn’t know any of this when three shots (yes, three) rang out

1,036 days into his term. All we saw was heroic King Arthur saving us

from nuclear annihilation, and then, with the speed of a supersonic

bullet, it was over. JFK’s violent death in the broad Dallas daylight

(coupled with the largely forgotten death of heroic cop J.D. Tippit, and

the knee-jerk murder of their killer two days later) whipsawed us back

into the old universe, where a glum, humorless LBJ now presided and was

soon sending many of our teenaged pals (not to mention between 1 and 2

million Vietnamese) to their deaths in a faraway Asian jungle. How could

a generation be expected to handle such trauma?

Unable to cope with this violent tear in the Zeitgeist, exaggerated

by the governmental secrecy that permeated the investigation into King

Arthur’s dethroning, we mourned until February of 1964, when four

British rockers, gifted of not only talent but amazing timing, let us

know that it was okay to have fun again—and they would show us how. But

even they couldn’t completely heal the wound.

Kennedy’s entrance onto the scene inspired many young adults to join

government, while his exit did just the opposite: Young people began

turning against the government en masse. Just a year earlier most male

teens wanted to join the CIA and be America’s James Bond, a favorite

literary character of JFK’s, but overnight, the Agency became the enemy.

When Kennedy’s “best and brightest” encouraged a more malleable

president to escalate the war in Southeast Asia, the youth revolution

was engaged big time. The turnabout pitted patriotic WWII vets and their

kids against one another. It was ugly, and some familial rifts were

never repaired. To this day, conspiracy theorists, fueled by the global

soapbox for crazies called the Internet, regale their followers with

“evidence” that the FBI, CIA, Pentagon, Secret Service, Texas oilmen,

LBJ, French assassins, Wall Street swindlers, the mob, Clay Shaw, George

H. W. Bush, and even Jackie were involved in the crime, which Jack’s

brother Bobby covered up. The 50th anniversary of JFK’s death will be

emptying the loony bins of so-called experts trying to make a buck by

turning Americans against each other in one last Dallas-inspired

onslaught.

In truth, Kennedy’s and Tippit’s killer hated America, and he was

more successful in harming it than he even dreamed—not to mention that

Mrs. Kennedy, Mrs. Tippit, and Mrs. Oswald were now widowed mothers

raising seven fatherless children.

Thanks for nothing, Lee Harvey Oswald, you bastard.

Caitlin Vincent

Soprano, Camelot Requiem librettist, 28

Fifty years later, both of my parents remember exactly where they

were and what they were doing when they learned of President Kennedy’s

assassination. For those of us born decades afterward, however, it’s

difficult to view John F. Kennedy’s death as more than an entry in a

high-school history book. We know we should remember, and we know we

should mourn what was lost, but we can’t help feeling disconnected from

the reality of what happened.

When I wrote the libretto for the opera Camelot Requiem, my

goal was to somehow bring the events of that day into focus. Instead of

describing Kennedy himself, I decided to portray those who were closest

to him—his personal staff, colleagues, and family—and explore the unique

way in which his death affected each of them as individuals. When The Figaro Project

premiered the opera last May (with 10 Baltimore-based opera singers,

all under the age of 32), I hoped the audience would be moved by the

story we were telling. But, even before opening night, I knew the piece

had had a profound and lasting effect on the performers. The opera had

become an artistic bridge between generations, allowing us to connect

with a tragedy and a time in American experience far beyond the reach of

our own memories.

In 40 years, there will be only a few people alive who remember what

the world was like before President Kennedy’s assassination. Forty years

after that, there will be only a few people alive who remember what the

world was like before the Twin Towers fell. Between now and then, I

know this country and this world will experience many more tragedies and

many more days that make the history books and change the world

forever. My only hope is that there will still be artists, musicians,

and, yes, librettists to be inspired by these events and create their

own bridges to past generations.

Richard Vatz

Mass Communications professor, Towson University, 66

President John F. Kennedy’s assassination was a considerable shock to

a nation and to its youth, who viewed assassination as unthinkable. No

one knew that such a preeminent voice in American leadership could be

silenced so easily, though his values and words continued to resonate.

My field encompasses political persuasion and political speeches, and

this is where President Kennedy excelled. Look, for example, at two of

his most memorable and consequential speeches: the 1961 inaugural

address and his 1963 speech at American University. His inaugural

address was a brilliant tour de force, mixing Cold War-era toughness

with an articulation of American values. He stated clearly that the

strength and resolve of the United States should not be doubted: “Let

every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay

any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend,

oppose any foe, in order to assure the survival and the success of

liberty.” And in the most memorable line of his inaugural, President

Kennedy decried dependency and praised the individualism that has

historically made America great: “And so, my fellow Americans: ask not

what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.”

JFK also knew how to rhetorically advance peaceful positions with

fewer misperceptions of our primary enemy, the Soviet Union. In a

brilliant speech at American University after the Cuban missile crisis,

he offered a bilateral nuclear test treaty to the Soviets in the spirit

of changing the prevailing atmosphere of mistrust. He also said we must

not fall into the “trap” of seeing conflict as inevitable and the

Soviets as without virtue: “No government or social system is so evil

that its people must be considered as lacking in virtue.” This was quite

consistent with his inaugural admonition, “Let us never negotiate out

of fear, but let us never fear to negotiate.”

Kennedy was a great rhetorical president, exhibiting great American values and resolve.

Elijah Cummings

United States House of Representatives, 7th District, 62

When President Kennedy instructed our nation to “ask not what your

country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country,” countless

people from Baltimore and communities large and small across America

responded to that call to action with a strong commitment to serve.

During a time when hatred and vitriol seemed to be woven into the fabric

of our country, President Kennedy spoke to our humanity and reminded us

of our responsibility to build up one another and to help those in

need. That pillar of public service remains alive today—demonstrated by

the young person who decides to delay her career to volunteer for the

Peace Corps, which President Kennedy founded, or by a retiree who spends

his days teaching in an after-school program. President Kennedy changed

the trajectory of our country by reinvigorating us with a spirit of

service.

Sanford Ungar

President, Goucher College, 68

I grew up in a small town in Pennsylvania, the son of immigrant

parents from Central Europe for whom the American Dream was a vivid, if

modest, reality. I was raised to believe that our country was not just

exceptional, but as flawless as any could ever be—to trust that our

system of government, embodied by everyone from the policeman at the

school crossing to the highest officials of the land, would protect us

from any evil that might come our way.

The assassination of President Kennedy represented, for me and for

many other naïve members of my generation, the abrupt end of such

illusions. It not only disrupted our lives, but also caused us to

question our idealism.

I was in my college dining hall at Harvard when I heard the news from

Dallas. I immediately got on my bicycle and rode to the office of our

daily campus newspaper, The Crimson, where I stayed for 20

hours and helped produce a special edition and the next day’s

paper. Because JFK was a relatively young alumnus of our college—he’d

not yet celebrated his 25th reunion—we felt a special connection to him

and a duty to chronicle precisely what had happened. Those of us at The Crimson

were fortunate, in a sense, to have an outlet for expressing the

feelings of devastation we shared with everyone around us. But it could

not take away the sense that we had reached an unwelcome turning point

in our young lives.

Burt Kummerow

President, Maryland Historical Society, 73

I was in my first year of graduate school, studying classical history

at the University of Maryland, College Park. I was also a dorm proctor

and still involved with the weekend shenanigans of my fraternity. That

Friday, we were all gearing up for parties and, as I drove my Corvair

into a gas station, the first announcement came over the car radio. The

only information was that the President had been shot in Dallas, but I

can vividly recall the whole scene—the gray day and the tangle of retail

sprawl along University Boulevard. I drove back to the fraternity row

and found everyone glued to the black-and-white television images as

news trickled in. Walter Cronkite’s announcement, delivered with

controlled passion, became the image of the day. My other vivid memory

is the following Sunday when I had my TV turned on in my dorm room.

Walking into the room, I watched in disbelief as Lee Harvey Oswald was

shot dead. For the first time, we witnessed a whole series of national

tragedies on live television.

The so-called “happy days” of my young adulthood were filled with

paradoxes. Yes, it was an innocent time in many ways, but the threat of

nuclear war was always hanging around. The two weeks of the Cuban

missile crisis in 1962 had the feel of Armageddon. For me, that event,

pre-Vietnam, marked the beginning of the modern television news era. In

our 24/7 full color news cycle today, it’s hard to imagine everyone

peering at the grainy, faint images of talking heads, sometimes with

blinds drawn to block out a bright day.

Stephen Hunter

Novelist, 67, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and author of The Third Bullet

Lee Harvey Oswald is my father. I wish I had a better one, someone

noble, kind, self-sacrificing, and wise. But no, I’m stuck with the

surly, creepy lout who pulled the trigger three times on November 22,

1963 and turned everybody’s world upside down, though mine, as it worked

out, turned right side up.

His legacy to me was the conspiracy. Whether or not he authored one

is open to doubt, but it is certain that his sloppiness, stupidity, and

banality left large holes in the official narrative and smart guys were

quick to see the possibilities. The first, of course, were the

anti-Warren Commission agitators, who dominated the publishing world for

10 years. Between sorry Lee and slippery Mark Lane, the conspiracy, as a

literary conceit and as a believable construct, was validated.

That’s where I come in, as have dozens, even hundreds of other

thriller writers. I’ve waded in those murky waters for 33 years now,

coming up with all matter of devious gambits, suppressed coincidences,

and outsized egos to justify such concoctions on the 350-page scale. To

be sure, conspiracies had existed as fuel for fiction before: Richard

Condon’s great The Manchurian Candidate is one such, fondly

remembered. But Lee Harvey Oswald took the conceit and injected it with

steroids, filmed it in Technicolor, and added a $50-million f/x budget.

Twenty-two books later, I have lived happily ever after, even if no one

else has.

Freeman A. Hrabowski III

President, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

Nineteen sixty-three was a very significant year for America, and,

for black children in the Deep South, the year was even more momentous.

As a 12-year-old in Birmingham, I participated in the Children’s March

led by Dr. King and other civil rights leaders, and as a result, spent

five days in jail. After that march, our families were more hopeful than

ever as we saw that for the first time, people were talking about black

children having the same rights as other children—to drink out of the

same water fountains, to go to the same movie theatres, to attend better

schools with more resources.

We all remembered how supportive President Kennedy had been in words

and actions during the Children’s March. As 1963 continued, we witnessed

the integration of the University of Alabama, for which the National

Guard was mobilized. We watched people march on Washington to ask for

jobs and basic rights. We saw the bombing of the church and the killing

of my friends, the “four little girls.” Through all of these

experiences, John F. Kennedy was our president. For the first time in my

life, I could be proud to have a president who believed I deserved to

be treated like any other human. He represented for all of us the best

of humanity, someone who cared about other peoples’ children.

As I sat in my 10th grade social studies class, now 13 years old, I

found myself stunned, sickened, and shaken to the core when the teacher

announced with great emotion that our president, John F. Kennedy, had

been killed. And for the rest of that day, we all simply cried. I will

never forget the grief and despair that one sensed all around us in our

school and in our community. He had been the source of hope we had been

searching for, a symbol of enlightened power—someone willing to do the

right thing and who cared about all Americans, even little Negro

children.

It was a pivotal moment in America, as devastating as any in our

history. It was a time when we as a nation had to decide who we were.

What a shame that it sometimes takes tragedy to remind us that we are

all the same.

Lea Gilmore

Vocalist, civic activist, former deputy director of ACLU Maryland

There they were again. As a young girl, I looked up on the wall of my

great aunt’s house in Rockingham, N.C. and saw the trinity of framed

pictures that were in the homes of seemingly all my older relatives:

Jesus, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and President John F. Kennedy.

Although I was not born at the time of President Kennedy’s

assassination, his life and death had a profound impact on many black

families, including mine. My family members would often discuss where

they were, and what they were doing when they heard of Kennedy’s death,

just as my generation reminisces on the immense tragedy of September 11,

2001.

This year, our country commemorates 50 years since that dark day in

Dallas, and it is coincidentally the 50th anniversary of the March on

Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which was organized by, among others,

Bayard Rustin (an openly gay, black advocate who brought the teachings

of Gandhi to the Movement) and led by Dr. King. Although Kennedy is

often lauded for his civil rights record (which I believe should be the

legacy of President Lyndon Johnson), Kennedy was actually hesitant about

the march, its implications, and the possible fallout.

So what is Kennedy’s legacy to me? It is one of humanity—that great

men, like him and Dr. King, should not be deified, but known for all of

their human strengths and weaknesses. This knowledge gives us the

inspiration to know that we, too, can do great things. We can make real,

positive change living in this skin of imperfection and knowing there

is perfection in trying. The perception and reality of President

Kennedy’s accomplishments and fallibilities is a human story. I am

critical of many of his actions and grateful for his journey towards

justice. As President Kennedy once stated “As we express our gratitude,

we must never forget that the highest appreciation is not to utter

words, but to live by them.”

Elaine Eff

Folklorist, author of The Painted Screens of Baltimore: An Urban Folk Art Revealed

In addition to the visual memory of the spot where the news reached

me—in Forest Park High School, under the clock in the entry hall at the

close of school—I more recently learned that John Oktavec, a close

friend and descendant of the man whose creativity ignited by own life’s

work, was born following the assassination and named for the fallen

president.

Keiffer J. Mitchell, Jr.

Maryland House of Delegates, 44th District, 46

I wasn’t born when Kennedy was around, but there’s a famous story in

my family. My grandmother was a civil rights attorney in the ’50s and

’60s. Kennedy called her house to inquire about some things that were

taking place, and she was in the bathtub. My uncle, who was 5 or 6,

answered the phone and had this conversation with Kennedy. He was

trained to say, “Who’s calling?” The caller said, “This is John Kennedy.

Can I speak to Juanita Mitchell?” He replied, “She can’t get to the

phone; she’s in the bathtub.” As my grandmother scrambled to get out of

the tub, my uncle had this little conversation with Kennedy about how

old he was and where he went to school—just a normal conversation with

John Kennedy.

Growing up and learning about the Kennedys, this was a family that

kind of brought majesty to the Presidency. But Kennedy also had a very

self-deprecating humor. He didn’t take himself too seriously, which

reminded me of one of the things my uncle [Clarence Mitchell III] said,

“Always remember, you put your pants on one leg at a time like everyone

else.” That even extends to the way in which he was assassinated,

because the Secret Service advised him to not ride in an open car, but

he wanted to do that.

I remember sitting in school years later and our teacher showing us

the actual news reports with Walter Cronkite breaking in on the soap

opera that was playing at the time. We were watching this video in

middle school and were very much riveted as if we were there. We were

all very affected by Cronkite saying Kennedy had died. Seeing the video

of the funeral procession—I remember bagpipes and marching drums—really

had an impact. As someone who grew up in a political family, here was a

young person—who was vibrant, with young kids—and he was assassinated. I

remember the youngest, John John, didn’t even realize what happened.

That had a big impact on me.

Kennedy’s influence was a call to service to young people—the torch

had been handed to another generation. It wasn’t just politics, but also

civil rights and public service. Under his administration, there was

this idealism. You had young people in their 20s or 30s who were key

advisors to him. You had young people dropping out of college to be

apart of the Peace Corps. There was the sort of idealism and innocence I

don’t think you will see again.

Jess Mayhugh

Senior editor, Baltimore magazine, 27

The 50th anniversary of John F. Kennedy’s assassination came up recently during a dinner with friends, all in their late 20s, early 30s. Mind you, we were hardly in an intellectual setting—Ocean City isn’t exactly a hotbed for political banter—but the conversations were thought-provoking nonetheless.

“He seemed like a politician people could relate to,” my one friend said, after explaining that she had just seen The Butler (which features James Marsden playing JFK).

“I don’t know. To me, he seems overrated,” another friend interjected confidently. “It was all golden and Camelot, but I wonder how much he would have been revered if he wasn’t assassinated.”

“He was actually shot 20 years to the day before I was born,” a third friend mused. “Yeah, November 22. I should probably care more about it. But it was so long ago. I don’t really think about it.”

I found it striking that each of my friends had a specific take on JFK. After all, not only were none of them born at the time of the assassination, but their parents were just kids. But the mere fact we were even talking about him meant JFK’s legacy still resonates with our generation—and continues to 50 years later.

When you begin to think about it, it’s easy to see why. Clues to his enduring impact are all around us. The Kennedys are pervasive in pop culture—whether it’s an Oliver Stone movie, a Marilyn Monroe joke, a heavy Boston accent from a Simpsons character, or a pivotal season-ending plot point on Mad Men. Also hard to ignore are the parallels between him and our current president—the good looks, fashionable wife, and two young children playing on the Oval Office rug and White House lawn.

And, like my one friend pointed out, Kennedy was relatable—the young president represented progress. Similarly, during President Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign, I felt more engaged in politics than I ever have—a sentiment I know was echoed on college campuses and in urban settings across the country.

Kennedy was also able to connect with young people, as well as break the Irish-Catholic barrier, engaging an entirely different demographic. Obama, of course, achieved a similar and monumental feat. Seeing an African-American get elected President was a pivotal moment for our country, and a milestone that many wished civil-rights champions—like JFK himself—were still around to see.

But regardless of these connections, the assassination itself will never pack that visceral wallop for me that it did for those who were alive. My dad, for example, was only seven years old at the time, but his memory of the incident is vivid. He recalls the hallways of his elementary school, the teachers scrambling when the news broke—and, of course, the live TV coverage when Lee Harvey Oswald was shot in front of millions.

I have heard plenty of these “You know exactly where you were” stories and the only way I feel like I, or anyone in my generation, can relate is to think back to the panic of 9/11. “I remember walking to my first class when one of my friends ran to me, shouting, ‘We’re at war! They’ve attacked the World Trade Center!’” recalls local opera singer (and millennial) Caitlin Vincent, who recently played Jacqueline Kennedy in Camelot Requiem. “September 11 will always be the date when the world changed forever: transforming from one we thought we knew to one we knew to fear. November 22, 1963 is a date of similar significance for the baby boomer generation.”

Like Vincent, I imagine that panicked feeling was similar to that horrible day in November. Of course, news about the Dallas shooting trickled in slower than it did in 2001. The world watched Walter Cronkite with bated breath, instead of being able to follow updates on CNN.com. All eyes, I’ve heard, were glued to TV sets, and the world seemed to shut down as an era—characterized as Camelot—had come to an end.

That era, though well depicted in history books and on screen, is another concept that’s difficult for those of my generation to connect with. We never lived it, of course, and our associations with the Kennedy clan have less to do with Camelot and more to do with the so-called “curse.” Since the assassination, the Kennedy family has been pummeled with one ill-fated event after another—Bobby Kennedy’s assassination, the Chappaquiddick incident, other car crashes, a skiing accident, and the death of John F. Kennedy Jr., to name a few.

I do remember JFK Jr. clearly—his handsome face plastered across the cover of People magazine. While he was certainly no president, the idea of his and his wife’s death made me realize that the story was still being told—the story of this huge Massachusetts bloodline being doomed for tragedy. Camelot, indeed, seems like just a fairy tale for those who weren’t around to see it.

But there was one time when the assassination felt very real—when I got an inkling of the incident’s power. In a college journalism class, our professor showed the Zapruder film of Kennedy being shot in Dallas. That slow-motion footage is now forever ingrained in my mind, where I’m sure it resides for many others. Some classmates even had to leave the room because it was too intense. But this was the first time I really watched. No longer was this just the 35th president on a term paper. This was a man, whose wife sat beside him as his brains were blown out of the back of his head. This was a man who was just trying to do his job—in a top-down convertible at his insistence—one crisp November afternoon.

Probably the most haunting part of that film comes right before he is shot, and that is the image that resonates with me, that is the image I see in my head when I think of John F. Kennedy: a blurry, Technicolor frame of a handsome man waving to the crowd, an eternal symbol of what could have been.