Reverend Donté L. Hickman Sr. and David Warnock

The Southern Baptist Church pastor and GBC chair discuss Baltimore’s recent upheaval, systemic blight, and the need for greater investment in city neighborhoods.

By Ron Cassie

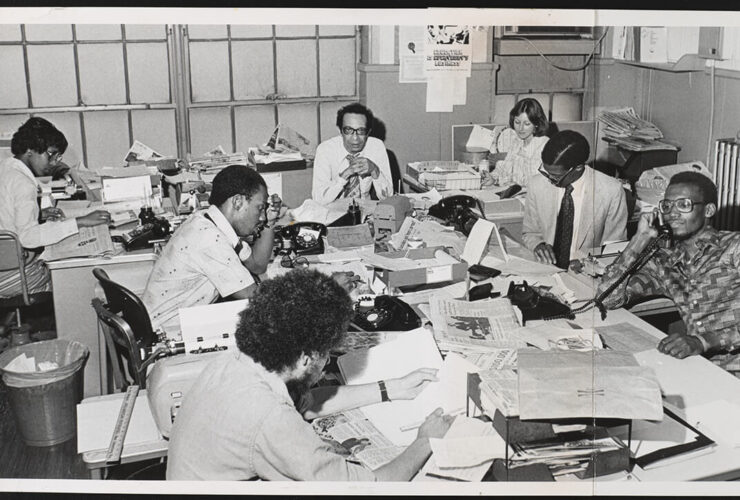

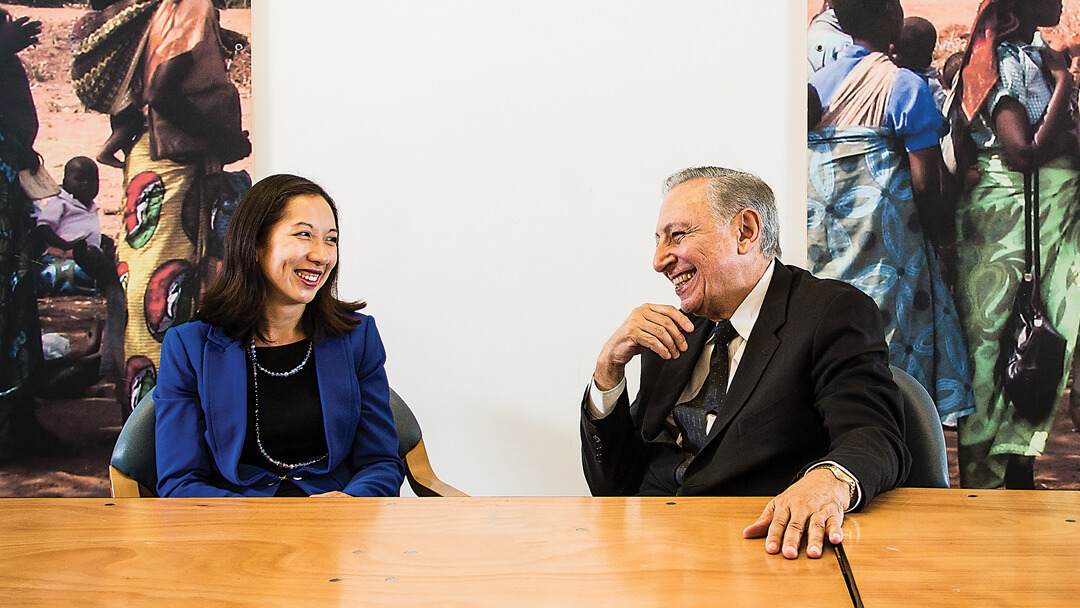

Reverend Donté Hickman Sr. and David Warnock at Warnock’s office in July.—Photography by Mike Morgan

Readers may remember Reverend Donté L. Hickman Sr. being interviewed on live television on the night of the Freddie Gray riots. As his church-sponsored senior center, under construction at the time, burned to the ground, the Baltimore native vowed to rebuild—plans that are now moving forward. David Warnock, managing partner at the private equity firm Camden Partners, is involved in several nonprofit organizations, including the Center for Urban Families, and also co-founded the Green Street Academy charter school in 2010. Their conversation began as Hickman noticed a photo of Warnock with Muhammad Ali in Warnock’s Inner Harbor office.

David Warnock: A friend’s father-in-law put a syndicate together—[Louisville, KY] investors—so Ali could turn pro. They backed him. Ali was always really loyal to them because they were the people that gave him the capital to start professional training. A bunch of local businessmen in Louisville.

Rev. Donté L. Hickman Sr.: That was a great investment. I wonder what they saw in him.

DW: He was a son of Louisville and he’d just won a gold medal in the Olympics.

DH: Which is probably a great segue to the conversation. What did they see in him to make that kind of investment, and then, be satisfied with not necessarily getting any reward from the risk they had taken? When I look at Baltimore, that’s the question I think has to be asked of people of means and also of motivation.

“The people, in my estimation, are the gems, the hidden treasures of this city.”

DW: I think to some extent it starts with celebrating excellence. In the wake of Freddie Gray, one of the things I think we as citizens of Baltimore, particularly as opinion leaders in Baltimore, have to do is talk about what’s really great in Baltimore. What are the things that pull us together—not divide us? And people of means need to understand that you can’t harvest the fruit of the city without planting seeds in different parts of the city.

DH: Before you got up to talk at the Greater Baltimore Committee event [the organization’s recent 60th anniversary annual meeting], it seemed like I was in a backroom board meeting with people of like minds and means who were somehow telling themselves, ‘Everything is settling down. We’re okay. We can go back to business as usual.’ And I was disgusted, [thinking] ‘They’re not getting it’. And then you made a speech and talked about the necessity of human capital and social transformation, and it was like a breath of fresh air. I wondered if it resonated within that environment, but it said to me there was somebody with means who has the right motivation that could possibly help to turn this city around.

DW: That was an important opportunity to link economic development to social change because I don’t really think you get one without the other. The fact is, everybody lives in their own echo chamber in some sense. [But] think about the people who have expungeable records. [Being able to expunge a criminal record] is good for people in the workforce and it’s good for business. When you talk to the business community, it’s like any other constituency: You have to explain the connections to them.

DH: For as long as I can remember coming up in Baltimore, the focus has been on the physical structures. I remember as far back as William Donald Schaefer being mayor and his vision of the Inner Harbor and what it could produce. But what gets lost in Baltimore is when we look at the physical structures as the strength of the city—we see the people as not as important. The people, in my estimation, are the gems, the hidden treasures of this city. Without impacting people, creating opportunities for people, identifying who the people are and what you can do to bring out a spark from them, hope from them—you are going to see dilapidation across the city. During the Freddie Gray events and all that mayhem, I saw the National Guard protecting the physical structures, but not protecting the communities and the people.

DW: Right. When you show leadership and say, ‘We are not going to have a safe city, we are not going to have a prosperous city, we are not going to have a city that’s looked upon by the international community or the media as a place where people want to come unless we think about the fortunes of the least fortunate among us.’ Well, yeah, that’s right. West Baltimore is tied to the Inner Harbor.

DH:

I saw the National Guard protecting the ‘gem’ of the Inner Harbor, but they allowed the communities, the businesses, and the pharmacies where people live

to be looted and burned down. . . . And I still couldn’t see the people as the problem. I saw systemic oppression as a deep problem. I am a product of West

Baltimore, of Edmondson Village, as an exception to the normality. Although there are many exceptions, many people found a way. There are so many in that

community who are gifted.

Reverend Donté Hickman Sr. and David Warnock discuss the important of community in Warnock’s office in July.—Photography by Mike Morgan

DW: Everybody has a dream. But do you have a tool kit and the backing to fulfill your dream? It’s about giving people the tool kit. That’s what we’ve got to focus on in our city, as individuals. . . . I’m interested to know your observations of the riots. I think the leadership that you [the clergy] all showed was important.

DH: It was surreal. Many pastors didn’t want to go in the street that night. We said, ‘We have to go, we need to be a ministry of presence and try to quell the chaos.’ I thought it was a necessary chaos because people had felt like they’d been unheard. Nobody is engaging, nobody is investing . . . Somehow the victims are looked at as the perpetrators of all the violence. I think that people had to lash out to voice themselves—granted it was in a destructive way. But how do we turn that destruction around and how do we transcend those fires to be light in areas that have not received attention, that, quite frankly, the city should be embarrassed about? As I sit here today [looking out toward the Inner Harbor], I look around and wonder, ‘What city am I in?’ as compared to the community that my church exists in.

DW: There’s an old phrase: ‘Character is what you do when no one is watching.’ The business community and political community need to think about solutions that aren’t framed in election cycles, that aren’t framed in activities with an eye toward the primary. Baltimore needs solutions that are done with an eye toward what this city is going to look like for the next generation and not what this is going to mean to my annual meeting, or my tax return, or my re-election.

DH: Most elected officials are about the groundbreakings and the ribbon cuttings that are coming within the season of their administration so they can pin another ribbon and move to the next position. Which means we have to start looking at the people we elect in a different way, who, as you have said, have character when no one is watching—when there is not so much of a tangible reward. We need people who can invest in the sons of Louisville. n

-

Kwame Kwei-Armah & Lawrence Gilliard Jr.

-

David Simon & Laura Lippman

-

Dr. Leana Wen & Dr. Robert C. Gallo

-

Denise Koch & Stan Stovall

-

Josh Charles & Derek Waters

-

José Antonio Bowen & Shanaysha Sauls

-

Laurie DeYoung & Konan

-

D. Watkins & Clarence M. Mitchell IV

-

Gaia & Doreen Bolger

-

Deb Tillett & John Davis

-

Damian Mosley & Linwood Dame

-

A Conversation with Dan Deacon

-

The Burning Question

-