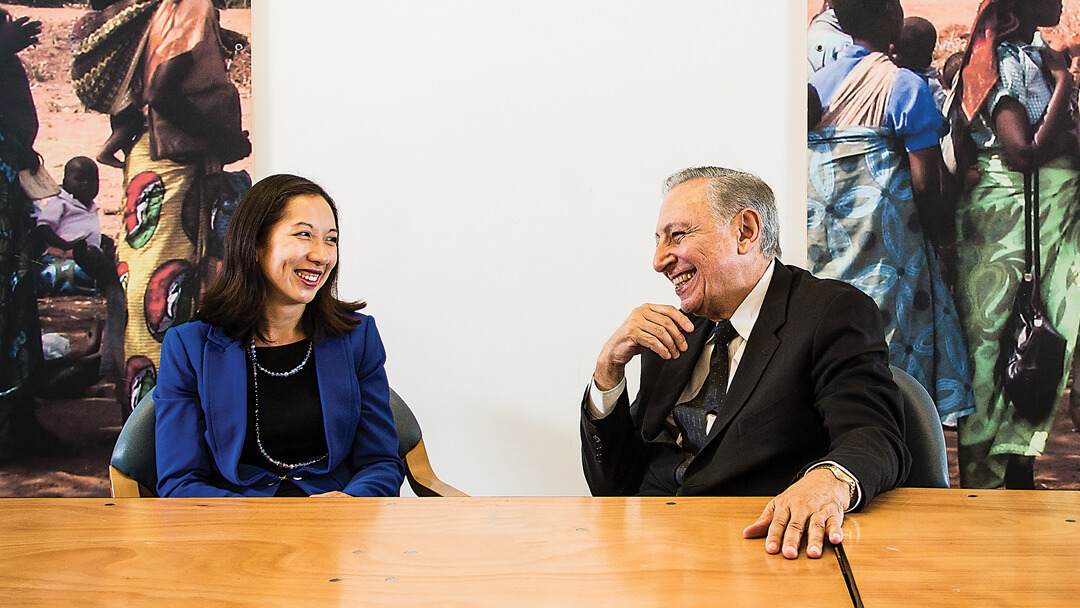

D. Watkins and Clarence M. Mitchell IV

The East Baltimore writer sits down with the former state senator and host of WBAL’s The C4 Show to talk about police brutality, civilian review commissions, and how to ignite change.

By Ron Cassie

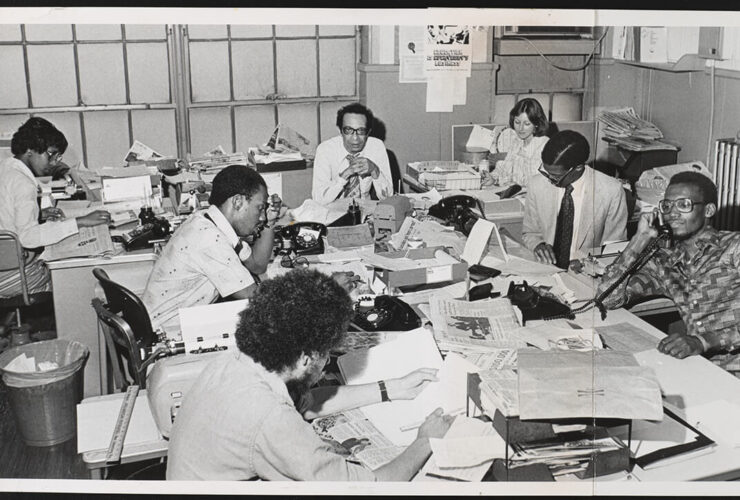

D Watkins and Clarence M. Mitchell IV shake hands in the WBAL studios in July —Photography by Mike Morgan

As the grandson of Clarence M. Mitchell Jr., the NAACP’s chief lobbyist during the civil rights era, and Juanita Jackson Mitchell, the first African-American female lawyer in Maryland, C4 brings a wealth of institutional knowledge to his topical radio show. D. Watkins has taught at Coppin State University and writes regularly for Salon and occasionally the City Paper. A collection of his essays, The Beast Side: Living (and Dying) While Black in America, will be published this month, and a debut memoir, The Cook Up, is scheduled for release in January. They met for the first time at WBAL’s studios, with Watkins explaining that while he was looking forward to writing about something other than police brutality for a change, he was more than happy to discuss the biggest issue currently playing out in Baltimore.

D. Watkins: Honestly, teaching is what I love to do more than anything. . . . [But] I’ll write for anybody and everyone. I’m writing something under a pseudonym now that’s going to be kind of funny. I’m trying to get into different lanes and directions. I get it, police brutality exists. I’ve just written about it so much.

Clarence M. Mitchell IV: But you want to do other things.

DW: I just need a break, you know? [But] not a break from this. I can start. . . . Sometimes when I talk to politicians, they talk in numbers: ‘There’s 37-percent less people getting their heads knocked off.’ Yeah, but okay, that’s still too many people. You have a strong family history, you know a lot of people in the community as well as people who deal with some of these issues. How do you navigate in those two worlds?

CM: I grew up as a child around issues of police brutality. My grandmother, Juanita Mitchell, used to represent people pro bono in police brutality cases when I was 7, 8, 9 years old. My great-grandmother, Lillie May Jackson, who was president of the NAACP from 1935-1970, had a place called Freedom House, which, if you drive down Druid Hill Avenue, is across the street from Bethel [A.M.E. Church]. Freedom House was a place where people could come to share stories about police misconduct or discrimination, unemployment, whatever. So the background I come from is learning about these one-on-one stories and then bringing the one-on-one stories to the reality of how you implement public policy.

DW: It [sounds] like your own personal journey has been a great tool and a lot of politicians don’t have that. What do you think of our [police] civilian review board now?

CM: Oh, it’s horrible.

DW: It’s nonexistent. It’s like one person with a million cases, who works every fourth Sunday.

CM: When I was in the House of Delegates, we tried to get a civilian review board bill passed for a few years. It never passed. The reason we got one passed in ’99 when I went to the state Senate was because state Sen. Joan Carter Conway . . . she was actually coming out of her office on Monument Street and saw a young child hit by a car. There was an ambulance there and so she goes over, it was right in front of her office, ‘What’s going on? May I be of assistance?’ The EMS person tells police, ‘Get this person away from me’—he doesn’t know who she is. They arrest state Sen. Joan Carter Conway. Handcuff her, put her on the curb, take her down to Central Booking. Guess who her lawyer was? Baltimore City Councilman Martin O’Malley. All that led to us crafting a brand-new civilian review board bill.

“When I was coming up, if you didn’t play basketball, you were selling crack.”

DW: It makes so much sense to have one.

CM: It doesn’t make sense if you are a police commissioner and a mayor who don’t want the public knowing you have police misconduct. It’s not a good idea if you don’t want people knowing what’s going on, which a lot of people believe happened, particularly through the O’Malley administration years, when aggressive, zero tolerance-style policing really escalated. We saw 100,000 people in Baltimore locked up each and every year. Even under Sheila Dixon and Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, [the civilian review board process] hasn’t changed much.

DW: [Recently], I went to a town hall with some people from Canada who came down and talked about how their civilian review board system is set up, and it works.

CM: When they say it works, what does that mean? That officers get fired?

DW: That officers get held accountable. Citizens have actual power.

CM: Let me ask you a question. When you look at what’s going on, from a younger perspective—because I’m 53. I don’t know how old you are?

DW: I’m 34.

CM: We’re a generation apart. When you look at things, do you see hope in addressing some of these problems, particularly in Baltimore? Do you see people trying to make a difference and coming together to do something?

DW: Yeah, I do, actually. But it has nothing to do with the system. It has nothing to do with education. It has nothing to do with the police department. It has nothing to do with trusting some of the policymakers. It’s independent artists, independent filmmakers, independent people who are achieving mastery in their fields and sharing those skills with younger people. When I was coming up, if you didn’t play basketball, you were selling crack. Flat out. There were no writers, there were no filmmakers, there were no dudes walking down the street like, ‘Yo, I design fashion.’ None of that was out when I was a kid. It was crack—and basketball.

CM: Those were the two choices.

DW: Obviously, there are some people who went to school, but these were the two hottest things. Now, there is a brand-new creative wave of artists and people who are really out here making it cool to organize, and making it cool to be smart.

CM: Here’s my question. Are they organizing just to organize? A lot of people meet just to meet. Are they organizing around changing public policy, or are they meeting basically just to bitch to each other?

DW: I get it. Yeah, I’ve been to all of them. Some of them are on a power trip. Some of them want to organize, but they don’t know what they’re organizing for. I’m more focused on people who know what their talent is. I’m starting on something where I’m going to be training young journalists and young people to document the stories of people who have been in Baltimore for generations. Baltimore is potentially on a path to be like D.C. or Brooklyn. A city that’s not like the Baltimore we know—not a Baltimore that you know, or that I grew up to know—but a different place through urban renewal and gentrification.

CM: [For] a whole bunch of reasons.

DW: So I’m teaching these young people how to conduct interviews, edit them, and then we’re going to archive them on a website as a method to preserving the history of the city that we love. That’s my contribution. That’s a small thing.

CM: No, that’s huge.

DW: My friend Devin Allen, who shot the Time cover [of the Freddie Gray riots], he’s doing the same thing with photography. My friend Aaron Maybin, who was a former NFL guy, who is a visual artist—he’s doing it with art. We’re all connected. We are all trying to reach mastery in the things that we love and to spread those skills. That’s the change that I’m seeing and that’s the most effective thing for me. I can sit here and say I want to organize a group to end systemic racism. I know that maybe it can happen, but I’m probably going to be dead for 200 years first.

-

Kwame Kwei-Armah & Lawrence Gilliard Jr.

-

Reverend Donté L. Hickman Sr. & David Warnock

-

David Simon & Laura Lippman

-

Dr. Leana Wen & Dr. Robert C. Gallo

-

Denise Koch & Stan Stovall

-

Josh Charles & Derek Waters

-

José Antonio Bowen & Shanaysha Sauls

-

Laurie DeYoung & Konan

-

Gaia & Doreen Bolger

-

Deb Tillett & John Davis

-

Damian Mosley & Linwood Dame

-

A Conversation with Dan Deacon

-

The Burning Question

-