News & Community

What's Next?

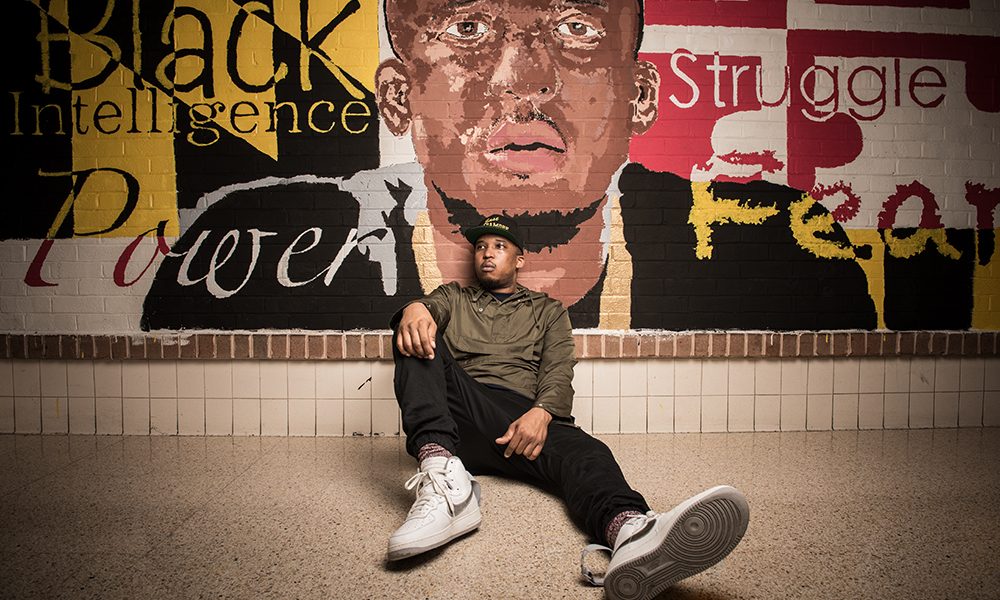

An essay by D. Watkins on the importance of mentoring black youth and becoming a voice for the future.

“Everybody watches movies, D! TV and movies!” my friend Rello said, pounding a basketball against the pavement and in between his legs. “You gotta make a film, not everybody gonna read books! But everybody watch the tube!” Some of our crew nodded in agreement. About twenty of us twenty- or thirtysomethings eclipsed the corner of Lakewood and Madison on a semi-warm April day. I was trying to get half of us down to Bocek Park for a 5-on-5. “They gonna read my book, homie,” I said. “I can sell! Man, I could talk a Nazi into donating money to the United Negro College Fund if I wanted to!”

The block laughed. We traded a few more jokes as we limped our way down to the court. Limped, because East Baltimore is rough on the bones—the lot of us have been beat, shot, stabbed, or suffered from some type of dirt bike injury.

Rello elevator sales pitched me all the way from Lakewood down to the court. He had some great ideas, but I had to school him on how the pen is the foundation. “We can make hella films or TV shows,” I told him. “But somebody is writing them! Most of your favorite films were probably books first!”

We reached the park. The court was limp and cracked like us. They painted it a fresh coat of red and blue the previous summer, but that last Baltimore winter made the rehab temporary. We didn’t care; we just wanted to compete while knocking off a few pounds for the summer.

Three or four games in, a black Honda pulled up. Q, another from our block who used to ball with us, hopped out, squeezing his iPhone. I haven’t seen him in person since he discovered Twitter.

“Yooooooo!!!!!” he said. “They killed that boy Freddie Gray from over west, yo! Slim died today! Bitch-ass, racist-ass cops!”

Obvious rage exploded from our side of the gate as some crowded his phone and some reached for their phones to watch the video, over and over again.

I didn’t know Gray personally, but he was tight with my friend GD, among others—Black Baltimore is small like that. We are all just one cousin away, really—everybody knows everybody. GD always called him Freddie Black because of his complexion. Gray was dark, slim in body, stood about yay high—and had a reputation for being a friendly jokester. Everybody knew he liked to clown, which made the cops who killed him even more evil in our eyes than the cops who usually kill people, and it was the primary reason for the actions that followed.

I allowed his ignorance to further perpetuate the angry, Black stereotypes.

Baltimore took to the streets in true Baltimore fashion shortly after Gray was pronounced dead. Cop cars were flipped like pissy mattresses and rumbles broke out as buildings burned—it got so wild that the National Guard parked troops with heavy automatic weapons and Army trucks on residential blocks. Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake issued a 10 p.m. curfew in the midst of the madness. I don’t have a press pass, but I scraped up enough clout as a freelance journalist to mostly stay above the curfew law. I tagged along with some Sun, City Paper, and Guardian reporters; together we documented the cocktail of pain and positivity that would grow to become the Baltimore Uprise.

Prior to the murder of Freddie Gray and the Uprising, I had documented Black culture for a number of publications, mainly Salon. My writings earned me two book deals and countless speaking engagements around the country as a go-to guy for a range of topics including police brutality, literacy, the digital divide, and systemic racism. I used a universally accessible language, I had a knack for discussing these topics to mixed audiences, and felt like I was doing my part to make a difference.

Gray’s death introduced my work to all of the major cable news networks. It gave me the opportunity to talk about these issues to a larger audience, with the hope of having a larger impact. My TV experience was limited—I had nothing under my belt except a few HuffPost Live interviews, but that was more than enough for the influx of reporters and producers that flooded every inch of Baltimore. They were everywhere: Don Lemon at City Hall, Geraldo Rivera getting laid out by activist Kwame Rose at the corner of Penn and North, Anderson Cooper mobbed by fans—and on and on and on. They were snagging everybody who was anybody to do interviews on Gray, our cop problem, and the current state of the city.

“Okay D, three shows reached out, they want to talk about your New York Times piece,” said Brandi, my event coordinator. “I’ll send you the location and hit times.” I had penned an essay for the Times the previous day on our city’s ugly history of police brutality and how growing up Black in Baltimore under Martin O’Malley almost guaranteed constant harassment and an arrest record.

The first few interviews went smooth. I talked about the collection of peaceful protests that went down, and how myself and other community members were going to play our part in repairing the damage. I also got a chance to shed light on the many systemic issues that cause all of these cop shootings. My language might not have been as effective as it could’ve been, but I got my points across. I felt good about all of my appearances that afternoon and even more confident about the one I had to knock out around 7 that night—OutFront, with Erin Burnett.

CNN was posted up on the corner near that park in front of City Hall. I strolled up to the set, and prepared to give the same spiel. Erin introduced the guests—me and some square ex-cop named Dan Bongino, who was over at CNN studios in Washington. I started off by talking about the positive things that were going on in the city, and even slipped in some jokes about how the peace rallies were so diverse that they looked like Black Eyed Peas concerts or Gap commercials.

“D’s words are inflammatory and irresponsible!” screeched a voice in my right ear. “And all he is going to do is run away when this whole thing blows up!” It was Bongino. They had told me he was a Republican who would position himself against me; but who knew the little guy would come out swinging?

I thought his claims were stupid and disconnected—I’ve never run from anything in my life, not even the police. I cut him off, telling him that he was annoying and blinded by privilege. His foolish statement gave me no choice. The smell of the streets still reeks from my pores, so yeah, I lost it. I went off on him and, as a result, I allowed his ignorance to further perpetuate the angry Black stereotypes that the mainstream media love to portray.

I’m not the only Black writer in the city. I’m responsible for making (other) voices heard.

I was upset with my performance, dismayed that a talking head could make me snap like that. Surprisingly, my mentions blew up on Twitter with praise from my side and hate from his—and now I was confronted with screenshots of his cubed-shaped head next to mine, up and down my timeline. I looked crossed-eyed and crazy on the streets, yelling at that phony in a safe and comfy studio who claimed that I ran from the issues that plague my city. I felt as dumb as he looked and decided I didn’t want to do TV any more.

Why do I need to be on camera? I thought. I was in the streets working with the kids who made the Uprise happen. They needed real love and support from neighborhood guys like me, especially since the mayor and the president instantly wrote them off as thugs. TV people should stick to TV, I thought, and I should write and do my community work. My event coordinator emailed a list of shows that wanted me on the next day, while square head continued to live on my feed as my social media followers tripled—but still, I was ready to cancel all of it just to focus on working with the people who I thought needed my help the most.

I flopped on the couch, cracked a soda, and started flicking through some of the cable news stations. Baltimore was 24/7. Some of the reporters were trying to do good work, but many were just blowing things out of proportion.

My phone buzzed and then made that annoying FaceTime sound. It was Rello. I didn’t answer because I thought it was a mistake. Grown men normally don’t FaceTime each other.

It rung again, same FaceTime ring, so I answered.

“Man why you take so long to answer! You too Holly Wood now! We saw you on CNN cookin’ boy! I’m proud of you!” he screamed. A small group of well-wishers peeked over his shoulder, forcing their way into the frame—my screen was full of gleaming Black faces. “TV, homie, the tube! That’s what I been tryin to tell you! I told y’all that I know D. Wats!”

“Yo, for one, I find it weird that you FaceTiming me, homie, we grown men, bruh,” I told him. “And two, I ain’t going back on TV, that clown made me lose it, I would’ve slapped his face off in real life!”

“Hang up D!” Rello said, “I’ll call you on the landline.”

A second later, he called back. “D, you are going back on TV man, these streets are fucked and we need you on TV. You speaking for us. You was saying the things we wanted to say, so finish your meal! Let them know how racist this dumb-ass system is, and how hard it is being Black in Baltimore, man—that’s your job! Finish your meal man, finish your fuckin’ meal.”

Rello was right. Black representation in the media is a little more lopsided than Trump’s hairline. TV, like print, is considered an authority—people see it and they instantly believe, and I can’t have people believing in Bongino. I started something and my people were backing me 200 percent, so I had the responsibility of being a voice—not the voice for every Black person in America, but a much-needed perspective from the Baltimoreans who are too often left out of the narrative. After our conversation, I went ahead and agreed to do spots and interviews at pretty much every station except Fox—and I made sure I exposed systemic racism on all of them. I communicated effectively in some, others were a little rocky, but I always got my point across. I played a small role in controlling the narrative.

As time progressed, I pushed harder to play my part in controlling that Black narrative. Not just by telling my story to the masses, but by setting up other writers to do the same. I don’t have the monopoly on the Black Baltimore perspective, and I’m not the only Black writer in the city, so I’m responsible for playing my part in making sure their voices are heard. I’ve worked with Tariq Touré, whose work was published in 1729 Magazine, where I also started, and now he’s writing for City Paper and dropping a book; activist Kwame Rose, who is traveling the country as part of the Black Lives Matter movement; and artist and former NFL football player Aaron Maybin, who gained recognition in The Sun. Young activists Chanet Wallace and Makayla Gilliam-Price are helping me on a website that captures Baltimore stories, and young spoken word phenom Kondwani Fidel is working to get his stories published, and navigate the publishing world, while getting enrolled in grad school.

I want to be that go-to person who helps others get their voices out—creating opportunities is just as important as gunning my own. Hopefully, I can do the same with Rello and his film. And that, as Rello puts it, is finishing my meal.

D. Watkins, a native of this city’s East Side, has been lauded by the editors of Baltimore magazine for his writings on such subjects as social change and race relations. In the wake of the death of Freddie Gray, he’s written for The New York Times, The Guardian, and Salon, among other publications, and published his first book, The Beast Side: Living (and Dying) While Black in America. Watkins, who teaches at Coppin State University, participated with talk-show host Clarence M. Mitchell IV in our “Conversation Issue” last September. His second book, The Cook Up, is being published this month.