Travel & Outdoors

The Shape of Water

The last vestige of a vanished fleet lives on through the art of Chesapeake boatbuilding.

in early August, Maryland summer has finally settled in and made itself comfortable on the low-lying land of the Eastern Shore. By 9 a.m., it’s nearing 90 degrees, and the humidity hangs as thick as molasses. The flags flutter low. The sailboats barely bob. Even the seagulls soar in slow motion, as if suspended in mid-air.

➤ Shadows cast on the Edna E. Lockwood.

Along the St. Michaels harbor, a slick sheen of sweat glistens on the skin of the boatyard crew at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum. Their hair lies wet at the napes of their necks, and their clothes cling tight across the thick of their backs. Even the widest of straw hats and the lightest of cottons do little to break this spell.

They work in the shade of the Edna E. Lockwood, who sits heavier than the weather—all 52 feet and 34,000 pounds of her, heaving fat and flush on the boatyard railway. She’s the reason they’re here on this blistering morning, as they have been for the past thousand days. She was born here, along these waters, over a century ago—an iconic Chesapeake Bay boat, part of an oft-forgotten fleet from the heyday of this estuary—and when she returns to them later this month, she will be the very last of her kind: a bugeye.

“Saving a boat like Edna is part of the way that we can come to understand our past,” says Pete Lesher, chief curator at the museum. “She is a quintessential Chesapeake boat in every respect, except for one—that she survived.”

By noon’s high tide, the young men guide her down the rails on an iron carriage, their eyes focused, their hands steady, listening to the clink and clank of hulking chains that lower her inch by inch toward the rippling waves of the wide and splendid Miles River. Thunderheads build in the distance, but against the hazy blue sky, her long, graceful lines have never looked more elegant, curving inward and billowing outward, much like the water itself.

There’s a lot resting on her, on the crew, on this moment. But without much ado, the last chains unfurl and it’s all over, having come and gone as quickly as the barely cool breeze. She drifts toward the water—a vision in white—and with little more than a splash, she floats.

➤ Old trees become a new hull; the boat lowers onto the railway.

With a scruffy beard, a few tattoos, and the occasional man bun, Michael Gorman is not your typical shipyard boss. For starters, he’s not a crotchety old man, waxing rhapsodic about the wooden boats of yore. “I don’t think any of us in this yard are the kind of people we see all the time, like, ‘This piece of wood sat in my shop for one full year and then finally told me what it wanted to do,’” quips Gorman. “We are not those people, and no offense to them. There’s just not much stroking of the old hull over here.”

With a scruffy beard, a few tattoos, and the occasional man bun, Michael Gorman is not your typical shipyard boss. For starters, he’s not a crotchety old man, waxing rhapsodic about the wooden boats of yore. “I don’t think any of us in this yard are the kind of people we see all the time, like, ‘This piece of wood sat in my shop for one full year and then finally told me what it wanted to do,’” quips Gorman. “We are not those people, and no offense to them. There’s just not much stroking of the old hull over here.”

➤ Michael Gorman

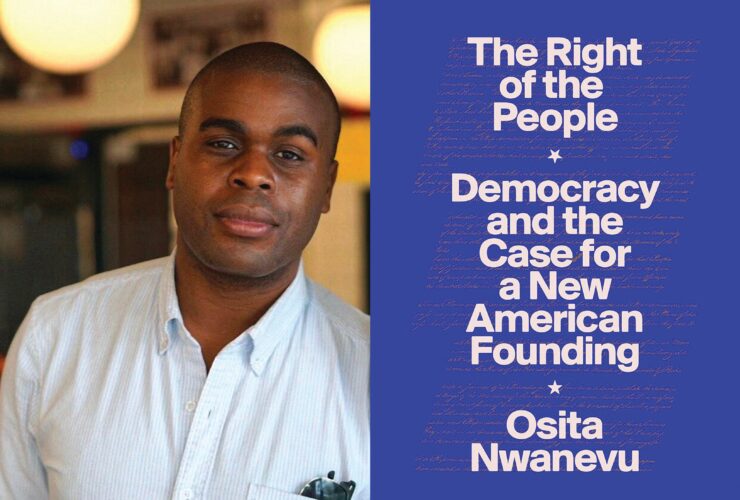

Still, this boat, more than three years in the making, has been an undeniable labor of love, and Gorman’s hazel eyes light up when he starts talking about the stories that she could tell. “You can recount a large chunk of the Chesapeake Bay’s history—people’s lives, their families, the waterways, the fisheries, industries like agriculture, timber, textiles, railroads, technology,” he says, “all through this boat and the way it was built.”

Edna was first constructed in 1889, a few miles west of St. Michaels on a spit of tidewater called Tilghman Island. But for Gorman, this all started in 2015 with 18 loblolly pines from a round-the-way forest off a family farm in Machipongo, Virginia. Thanks to their swampy location, these ancient trees had been skipped over for generations while their siblings were logged in yearly swoops. Trees so big—greater than 10 feet in girth and upward of 100 feet tall—that you could wrap your arms around them and your fingertips would never touch. Trees so old—nearing their second century—that they could have been passed by Union soldiers or runaway slaves. Trees so rare that it’s almost a twist of fate they would finally be felled only to remain on this tidal watershed, its tangled tributaries branching out like a labyrinth of roots.

These native trees mattered in order for Gorman and his crew—“the fellas,” as he calls them—to properly save the Edna, a National Historic Landmark. Sure, starting from scratch would have been easier—“if we wanted to turn out a replica bugeye, we could do it pretty darn quick,” says Gorman—but then the original boat would truly vanish. Instead, they carefully trace her lines, and, in turn, the trails of her builder’s ghost.

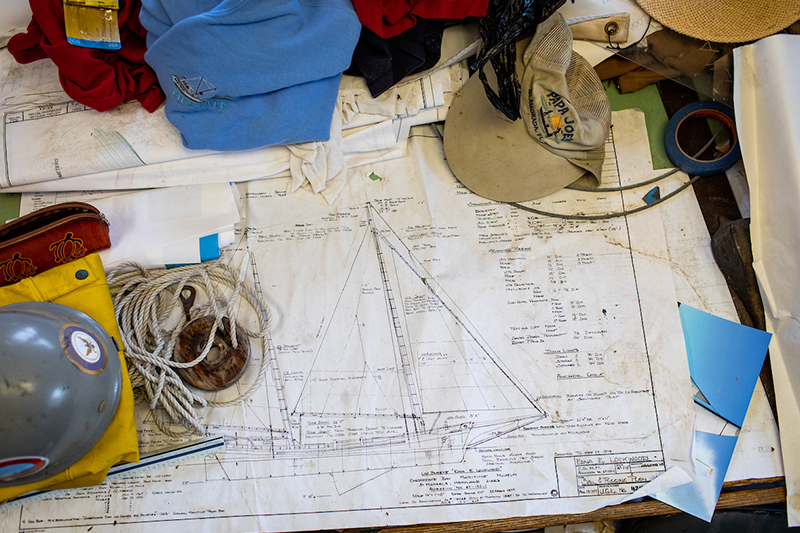

➤ CLOCKWISE, FROM Top: Clamps wait for work; the fellas paint the new hull; old maps and blueprints in the office; EDNA's plans.

But finding those trees was no easy feat, and after two years of searching, Gorman and his right-hand man, lead shipwright Joe Connor, had nearly given up and gone looking out on the West Coast before stumbling upon that Eastern Shore of Virginia farm owner and his fateful wood.

➤ The pines soak in the St. michaels harbor.

When the time finally came in early 2016, the pines were cut down, stacked on the back of a tractor-trailer, and hauled 150 miles north across state lines into Maryland and onward to St. Michaels. There, they were rolled into a quiet cove off the Miles, where they’d sit for weeks, then months, their rings curing in the brine of the brackish tide.

With the trees in their custody, Gorman and Connor, plus shipwright James DelAguila and apprentices Michael Allen and Spencer Sherwood, could finally get to work. Edna’s topside was in good condition, having been completely restored in the 1970s when she was donated to the museum. Her hull, however, was a different story, having deteriorated to the point of no return.

That fall, the loblollies were heaved out of the water and up onto the railway one by one by crane. Of the 18 trees, nine logs were selected for Edna’s new hull, each designated with a specific position, then draped in sweeping blueprints made using 3D technology from the National Park Service, all in order to recreate the very same timbers first pinned to her nearly 130 years ago.

Over the next few months and into the new year, the crisp, clean air fills with the thuds and whacks of adze and axe—archaic hand tools used to slowly carve the bulky blocks of pine into slight, sloping contours that will rest in the yard like whale bones. “It takes a lot of time,” says Gorman—nearly 40,000 man-hours when it’s all said and done—“but eventually it’s going to begin to take the beautiful shape of a boat.”

➤ clockwise, from top: Ropes idle on the old mast; the boatyard cat; a ladder leads into the hold below; Edna's topside, like shark's teeth; iron chains for hauling; deck work underway; old postcards hang in the office.

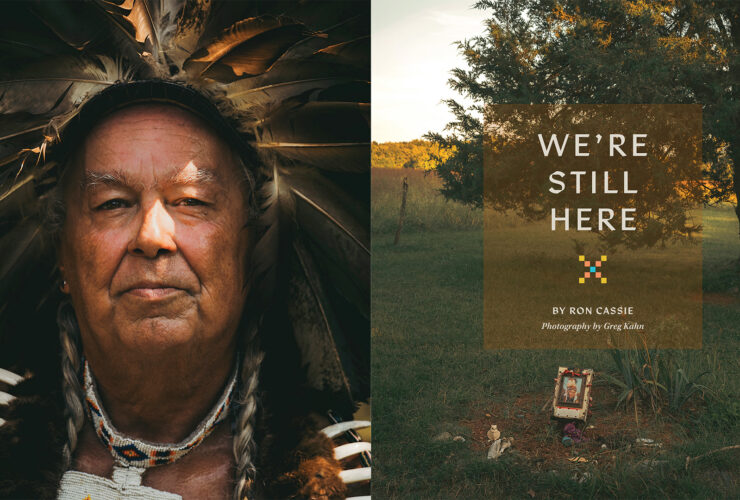

This method of boatbuilding is indigenous to the Chesapeake Bay, dating back thousands of years to when Native Americans first settled along these shorelines. Back then, the Eastern Shore was covered in old-growth pines, which were felled by fire and shaped by stone or shell into massive dugout canoes.

This method of boatbuilding is indigenous to the Chesapeake Bay, dating back thousands of years to when Native Americans first settled along these shorelines. Back then, the Eastern Shore was covered in old-growth pines, which were felled by fire and shaped by stone or shell into massive dugout canoes.

When Europeans arrived in the 1600s, they quickly took notice of the traditional craft—the way the boats’ fine ends and shallow hulls were ideally suited to the region’s flat and winding waterways. It wouldn’t be long before they began trading with the tribes, then hiring their builders and learning the techniques themselves. Their metal tools accelerated the building process, and soon enough they were joining multiple logs, adding masts and rigging, and transforming canoes into sailing vessels. Through the 1800s, these boats quickly grew in size before evolving into the largest and last of this lineage—the bugeyes—though few, if any, Native Americans were still around to see them.

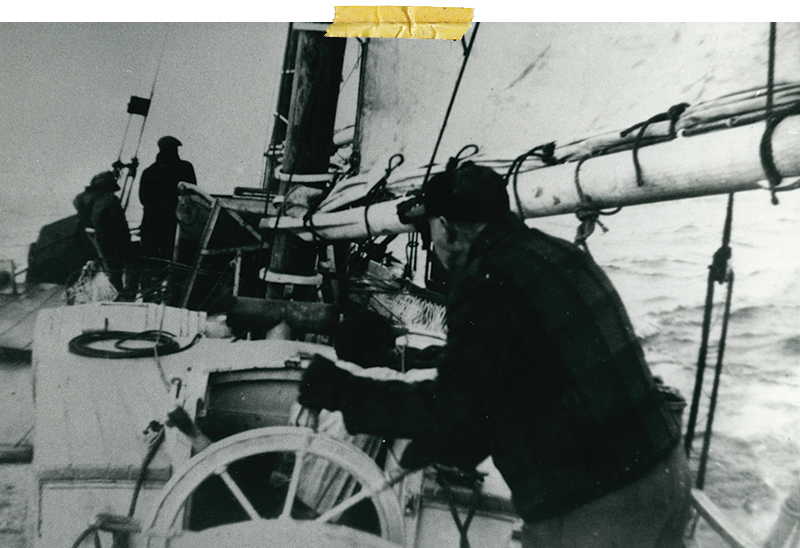

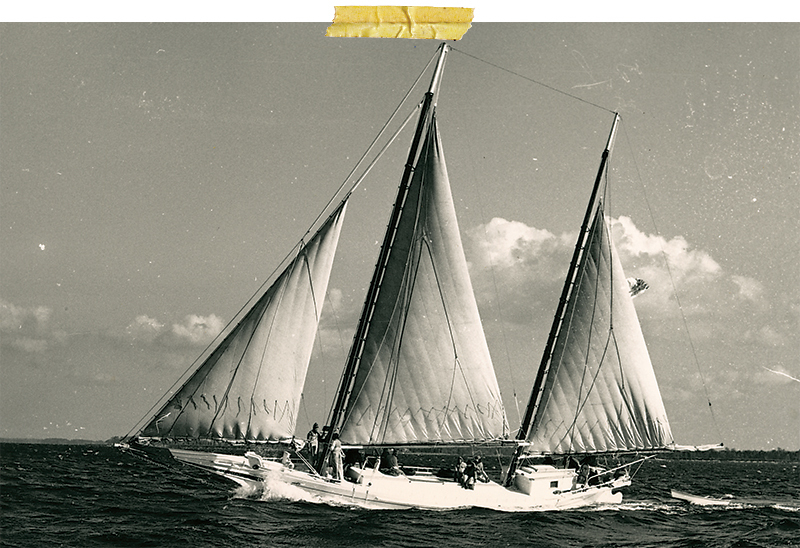

➤ Edna in high seas during the mid-20th century. Courtesy of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum

By the middle of the 19th century, bugeyes were like a flock of birds afloat on the Chesapeake Bay, their white gleaming wings appearing in the hundreds between the 1860s and the 1910s. At the core, they were workboats, and the job at hand was the bay’s then-abundant oyster. (The origin of the word “bugeye” has been lost to history, but many fittingly claim that the name hails from the Scottish word “buckie,” for shellfish.)

For centuries, Chesapeake inhabitants had harvested oysters using heavy hand tongs and human strength, but following the Civil War, iron oyster dredges were permitted in Maryland, and bivalves had become so popular that local watermen were in need of a strong and swift new vessel to both meet demand and carry the cumbersome contraption.

These broad and majestic ships were built specifically for the oyster fishery, still featuring the principal design of the log canoe but now made with upward of 11 logs, plus a wide hold for storing cargo and a small bunked cabin for the usual seven-man crew.

From fall through spring, they would leave the docks in the early morning darkness to drop their dredges at the first sign of daylight. Back and forth, they’d run the oyster bars, dragging up their catch and filling the boat’s belly with a battering of wet shells. When the holds were full, sometimes heaping up onto the deck like a mountain of soot-covered snow, they were off to market before beginning again the next dawn.

➤ An unknown bugeye hauling oysters. Courtesy of A. Aubrey Bodine

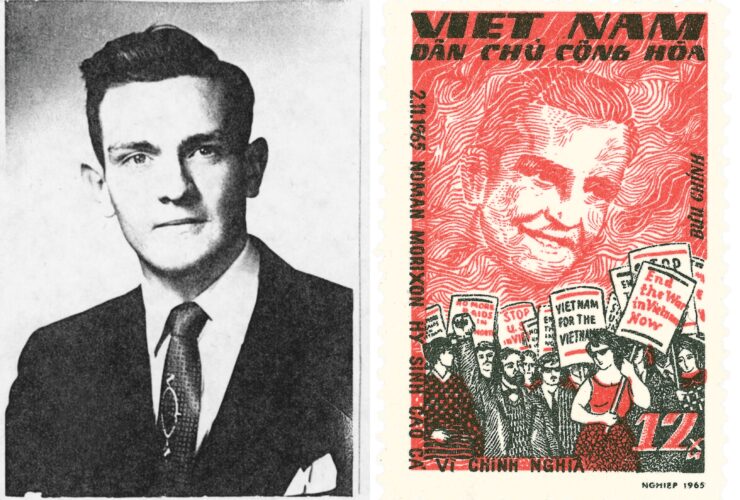

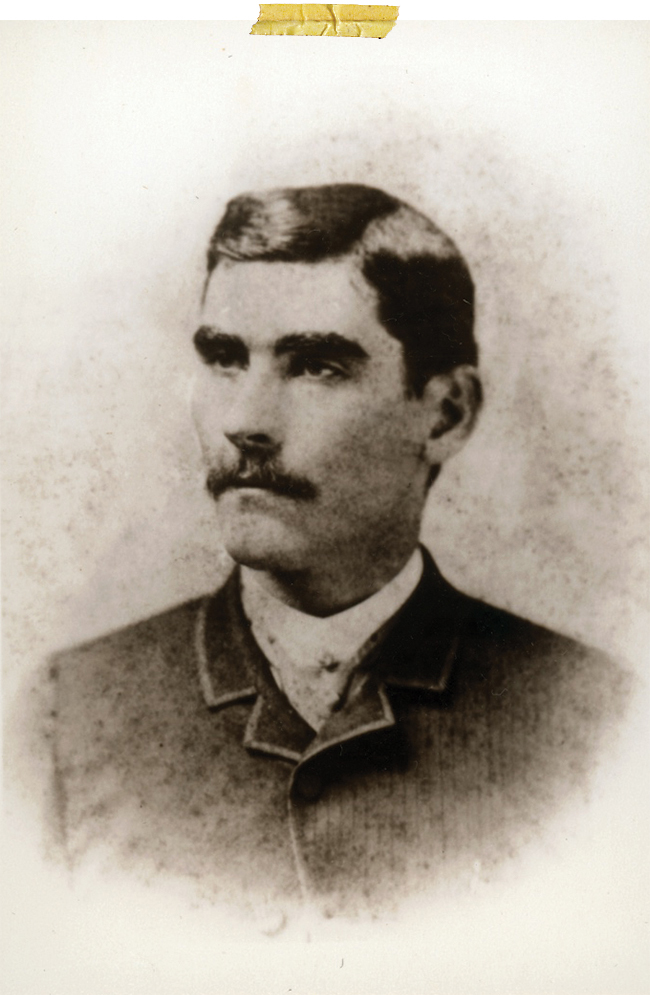

➤ John B. Harrison. Courtesy of THE CHESAPEAKE BAY MARITIME MUSEUM

Annapolis, Washington, and Baltimore, of course—then the oyster capital of the world—were all common ports for bugeyes. Throughout the winter, they would line the docks and off-load hundreds of bushels to buyers before a quick foray at the local pub. In the summer months, when oysters spawn, they carried produce—tomatoes, peaches, watermelons—plus grain and lumber to the big-city markets and mills. At the time, there were no bay bridges and few trains; the water was the road, and on it, bugeyes were the tractor-trailers.

Edna herself rarely ventured too far from home, mainly dropping her hauls along the Miles and Choptank rivers. She was built only a stone’s throw from both ports by the heralded builder John B. Harrison. At the time, Harrison was only 24 years old and had already built six bugeyes—“slightly intimidating,” says Gorman—and after Edna’s hull first hit the water in October 1889, he would go on to build another 200 boats and become one of the most skilled builders on the Chesapeake. “John B. was curious—the real Herreshoff of this area,” says Connor, referring to the revered Rhode Island naval architect—a sort of Elon Musk of sailing vessels. “To him, it wasn’t a job. It was the only thing in the world that he’d ever think of doing.”

Wooden boats lend themselves to wistfulness—“a disappearing art,” “a dying breed”—but boatbuilders, much like watermen, saw bugeyes as a tool that served a purpose, and their trade as just the tidewater way of life. As it still is today, “function was prized over form,” says Connor. “If the boat was strong and seaworthy, that was the most important thing.”

“You can recount a large chunk of the Chesapeake Bay’s history, all through this boat and the way it was built.”

During Harrison’s lifetime, there were scores of boatyards along the bay, with the most prolific bugeye builders hailing from Talbot, Dorchester, and Somerset counties to the east, as well as Calvert to the west, while Baltimore’s bountiful shipyards primarily produced large, sea-going vessels, such as schooners, and the city’s namesake clippers before that.

Despite their numbers, these were not grand or gilded places. “There was this innate conservatism among Chesapeake builders,” says Lesher, noting that few frills went into a boat’s construction beyond handy resources and scrappy know-how passed down among generations. At the time, large pines were still plentiful along the estuary, with dense stands of loblolly having yet to succumb to the teeth of sawmills. That mighty machinery had not yet arrived on this isolated terrain. Everything, for the time being, was still done entirely by hand.

➤ Joe Connor.

“Chesapeake boatbuilding is definitely a testament to doing a lot with a very little,” says Connor. “It’s a very American concept,” and bugeyes were born out of an era of “great American optimism,” as Lesher puts it—a time of industrial revolution, fresh-laid railroad tracks, westward expansion, and the exploitation of this new nation’s natural resources.

Despite the builders’ modesty, there was a quiet sense of pride that went into a boat’s construction, apparent from the intricate, hand-carved nameboards and gold-leaf embellishments down to the subtle nuances etched into every ship. No two bugeyes were ever exactly alike, each bearing the fingerprints of her individual craftsmen. “If [a boat] was a thing of beauty,” wrote historian Charles Kepner at the time of Edna’s 1970s restoration, “that was because the builder made it so.”

While Harrison gets the credit for constructing the original Edna, at least a half-dozen hands were likely to have played a part in her creation. As Gorman is in charge of the current job, recognition is due to the entire crew, including the later additions of apprentice Zachary Haroth, rigger Sam Hilgartner, and intern William Delano. There are also the countless volunteers who have lent a hand, up to the museum’s board and president, who made the nearly $1-million project possible.

“You can learn things from the archival evidence, but having the real example helps you make discoveries that wouldn’t appear on paper,” says Lesher. “The restoration adds a new layer, and then we’ll add another when we finally take her out for a sail. It gives us a deeper understanding of our past, and this is the last remaining opportunity for us to do so with the bugeyes.”

➤ Clockwise, from top: rusted tools; the fellas take lunch; readying the boat for the railway; Spencer Sherwood at work; organized chaos in the office; the boat shop; the old hull; Edna's plans; the docks.

For most of the boatyard crew, this is their first time ever working together, as each shipwright hails from a different city up or down the East Coast. Gorman himself landed here from his native New York after running out of money on a sailboat bound for Mexico, but he and Connor go back to college days, having met while studying at the Landing Boatbuilding School in Maine. “I like to think that I lured him here,” cracks Gorman, though Connor spent his childhood summers the county over, a self-proclaimed “river rat.”

For most of the boatyard crew, this is their first time ever working together, as each shipwright hails from a different city up or down the East Coast. Gorman himself landed here from his native New York after running out of money on a sailboat bound for Mexico, but he and Connor go back to college days, having met while studying at the Landing Boatbuilding School in Maine. “I like to think that I lured him here,” cracks Gorman, though Connor spent his childhood summers the county over, a self-proclaimed “river rat.”

➤ The crew and the crane operators.

The two interact like a classic old married couple, both relishing a good razzing before their first cups of coffee, as well as a round of Old Fashioneds after they clock out. But “it’s a wonderful treat to work with one of your best friends every day,” says Gorman, “and we have assembled a talented, liberal-minded, artist-approach boatyard here over the last four years together.”

“I don’t want to say it in front of them because they’ll all get big heads, but this is an amazing crew of inspired young folk,” says Connor, the oldest of the bunch at a mere 36. “The nature of this work beats you down; your joints ache, your back gives out. But the fellas bring a level of enthusiasm and also real expertise. At the end of the day, boatbuilding takes so many hands and so many hours. It’s definitely a team sport.”

➤ The fellas.

Each builder comes to the shipyard with his own stories and skill sets, and most of them have side hustles. Allen, 28, plays live music, while Sherwood, 24, dabbles in graphic design, and Gorman and Connor build furniture. Haroth, 32, is fixing up an old bus that he’ll eventually drive back to Seattle, while Hilgartner, 27, helped found a free college in Oakland.

Whatever their rank, there’s no attitude—no ego. Even through the most meticulous and mundane tasks, they share a mutual respect and genuine rapport. They literally whistle while they work, sporadically sing out a lone line of some long-lost country tune, and regularly shoot the breeze in the dusty break room, heckling each other and the old barn cat (also named Edna) before the bell tower rings and they’re back at work again.

Even in winter, they make it look easy. Out in the elements, they don knit caps and Carhartts, their beards grow long, and their summer tans stay as the snows blow in and the previous year whisks out. “November 1 through March 31, we’re cranking,” says Gorman, his hair tucked behind thick-rimmed glasses and into a faded trucker hat at the end of 2017. “It keeps you warm, there’s nothing better to do, and whatever the weather, this is the best office. When everyone else is complaining about going to work in the dark and getting home in the dark, we get to live in those eight hours of light.”

there was a quiet sense of pride that went into

a boat’s construction, apparent from the intricate,

hand-carved nameboards and gold-leaf embellishments down to the subtle nuances etched into

every ship.

➤ Planked up and ready for faring.

Despite their natural rhythms—the hypnotic hum of hand planers, the endless tap-tap-tap of chisels on wood—Gorman’s crew shows their greatest strengths in the face of the unknown. Boatbuilding is all about problem solving, and while true perfection can be aspired to, it is only found in the infinite number of obstacles overcome along the way. The crew has learned to trust their guts and hone their intuitions, finishing a task and standing back before starting the next one.

When Edna was donated to the museum in 1973, after a stint as a yacht with the Kimberly family of Kimberly-Clark paper fame, she was nearly a century’s worth of choc-a-bloc repair. “In horrible shape,” said the revered Tilghman builder Maynard Lowery, who helped oversee the restoration. The museum quickly moved in and completely rebuilt her topside, but nearly 40 years later, even some of those alterations would either rust out or rot away.

“This whole project has been us figuring out, was this just a fix or the way it was originally done?” says Connor, looking at the old jigsaw-like hull that has been cut away and saved for a future museum exhibit. “As we take the boat apart, how do we put it back together?”

Last fall, as the days grew shorter and the geese appeared overhead, the boatyard moved at a slow and staccato pace. Connor’s wife had a baby, and the rest of the crew took turns taking vacations. They’d spent the last two years tangoing with the schedule, and by this past January, they were coming out hot and catching up quick.

The beginning of 2018 brings blustery, sawdusty days, with the boat now cocooned in a colossal white tent to keep the wind at bay. Edna is marked with measurements—a miscellany of to-do-list minutiae—and for the next several months, the crew will be smoothing out (or “fairing,” in shipwright speak) the sturdy new hull that is now jacked up in the old one’s place. “It’s like sculpture,” says Gorman, who once studied the subject. “Day One was the biggest this boat will ever be. We’re now building by reduction.”

Beneath the pewter sky, each builder is in the zone as a flurry of blond pine shavings fall to the gravel at their feet, building in soft anthill piles, whipping in the air and sticking to their mustaches before blowing out to sea. This is meditative work, and much of it is done in silence, but they do stop to answer questions from museum visitors who stand in awe of Edna or to chew the fat with old-timers who saunter through and poke holes in the progress they’ve made.

After this spring’s final frost, the boat is nearly whole again. Much of the leftover loblolly has been milled into long planks, which are then steamed, bent, and clamped along the boat’s lines, filling the gaps between deck and hull until the final “whiskey plank” is placed and celebrated with a bottle of rye. They’ll continue to fair, sand, caulk, paint, fair, sand, caulk, paint on repeat for “what feels like an eternity,” says Connor, as the first buds bloom and the sun slowly gathers heat.

➤ Clockwise, from top: Rusted tools; THE BOAT's bow; Joe Connor operates a crane; a lone iron chain; hats and "Half Pint"; safety glasses for flying woodchips; edna's gilded name boards; her new centerboard awaits.

Bugeyes like Edna were constructed through the 1910s, but many would sail on for decades, through squalls and stock market crashes, well into the 20th century. She herself changed hands a half-dozen times but steadily plied the mid-shore bars. “If a boat continued to catch oysters, there was enough money to put back into its maintenance,” says Lesher. “The ones that survived did so because they earned their keep.”

Bugeyes like Edna were constructed through the 1910s, but many would sail on for decades, through squalls and stock market crashes, well into the 20th century. She herself changed hands a half-dozen times but steadily plied the mid-shore bars. “If a boat continued to catch oysters, there was enough money to put back into its maintenance,” says Lesher. “The ones that survived did so because they earned their keep.”

But by the end of the 1800s, Chesapeake oysters had already started to become badly overharvested, with some 14 to 20 million bushels hauled up each year in the previous decades. Maryland forests had been ravaged, too, with nearly all of those old-growth timbers now gone, leaving only smaller pines too skinny to build a working bugeye. In 2015, Gorman’s Machipongo stand was a white rhino, but after Edna’s logs were felled, so were the rest of the trees. Connor returned recently: “It was a real Lorax moment for me.”

Those giant sawmills had finally come online as well, and with them the invention of cheap sawn lumber, followed by a new, now-iconic ship. “If you asked a waterman in 1900, ‘What’s a skipjack?’ he might have given you a blank look,” says Lesher, but within a few years, these vessels were the shiny new pickup trucks built to replace the overworked bugeyes—far cheaper to construct and easier to maintain than their log-built predecessor. “Skipjacks might not have been quite as good of an oystering boat,” says Lesher, “but they were good enough.”

➤ William Delano, Michael Allen, and Joe Connor walk the plank; Zachary Haroth works beneath the new hull.

Most bugeyes were eventually worked into the grave, but a number did live on, having been converted into buyboats—the middlemen between watermen and market—though they’d soon all but vanish, too. “We tend to value things as they’re disappearing,” says Lesher, and in the bugeye’s case, that was too little too late. Wooden boat nostalgia didn’t gain traction until the environmental movement of the 1970s, and when she finally stopped oystering in 1967, Edna was the last working bugeye on the Chesapeake Bay. Today, the average Maryland resident has never even heard of these historic boats with their funny name.

Even by the time the museum was founded in ’65, “so many things about the bay were already changing,” says Lesher. “The end of steam service had just taken place. There were no schooners, one bugeye, and one oyster sloop. But there were a lot of skipjacks, and they have been preserved in numbers simply because they survived long enough.”

Now the prolific deadrise workboats speck the bay the way the bugeyes and even the skipjacks once did, roaming the shorelines in search of fat crabs and full oysters. Many are built out of the even cheaper plywood and fiberglass, a design that took hold in the 1990s, but watching them work the water today, still bewitching and so bound to Chesapeake ways, the question remains: When will they become the disappearing ships we need to save?

As with wooden boats, there are nowhere near the number of builders there used to be along the Chesapeake, but they are still out there, “making it, doing it, raising kids on it,” says Gorman. He can think of five such guys off the top of his head, all in his same age bracket, found down the shore in Maryland backwaters and across the bay into pockets of Virginia.

For the ones who do remain, wood has become a niche market, as few builders still consider the medium their bread and butter. The practice endures through small-craft hobbyists and restoration experts, but most have converted to those newer materials to craft workboats from the bottom up.

“To him, it wasn’t a job. It was the only thing in the world that he’d ever think of doing.”

These days, “you don’t really think you’re going to get a job when you start building boats,” says Sherwood, who came straight from school to this project. But wooden ones, whatever the size, are still the reason many get into it, even despite the modest pay. “The greater mission sucks you in—the stewardship of passing things on, the autonomy that comes with it,” says Connor. “In the beginning, we were cowboys, just figuring everything out as we went along.”

Most of the crew won’t easily admit that their trade is an art form, but the feeling is apparent in each furrowed brow and determined gaze. “Boatbuilding is a bit of an abstract,” says Connor. “Everybody has their own style. Everybody has learned from someone else. There are a million ways to skin a cat. But there is always some small version of self-expression every step along the way.”

➤ Afternoon light in the boat's belly; Edna moves in the air, on the railway, then back into the water.

The week before that sweltering summer morning, a crane arrived in St. Michaels and lifted Edna—now whole—into the air like a bold arrow, then back onto the railway. There she sat for a week, coming in and out of the August water, her planks swelling up around her cotton caulking, absorbing so much of the Miles into her porous new hull that she’d nearly double in weight. “She’s going to be a beast, a real Cadillac,” says Connor, “rolling through motorboat chop like it’s nobody’s business.”

The week before that sweltering summer morning, a crane arrived in St. Michaels and lifted Edna—now whole—into the air like a bold arrow, then back onto the railway. There she sat for a week, coming in and out of the August water, her planks swelling up around her cotton caulking, absorbing so much of the Miles into her porous new hull that she’d nearly double in weight. “She’s going to be a beast, a real Cadillac,” says Connor, “rolling through motorboat chop like it’s nobody’s business.”

Once she’s watertight, Hilgartner will install her rigging. Her old masts will go up, her new sails will flutter out, and she’ll get a final coat of paint—that traditional bright white topside and brick-red bottom—before her big day.

She drifts toward the water—a vision in white—And with little more than a splash, she floats.

When that time comes and she slips back into the harbor during the museum’s annual OysterFest on October 27, there will be much fanfare, just as there was when she was first launched off Tilghman Island this same month in 1889, and then again, from this very spot, in the 1970s. Now, as then, the townspeople will gather at the water’s edge and, with a bottle of champagne broken over her bow, she will be christened with wishes for fair winds and following seas. Flags will wave. People will cheer. Oysters will be shucked and devoured.

Nothing will remain from the original boat besides a 130-year-old silver dollar fastened to the bottom of her mast, which raises an age-old paradox—a matter of identity, debated among great philosophers: After a boat is rebuilt, does it remain the same ship? Though similar in build and steadfast in spirit, will she still be the Edna E. Lockwood? “As the old saying goes, my grandfather’s axe has had two new heads and three new handles,” says Morris Ellison, museum volunteer and mentor for the crew, “but it’s still my grandfather’s axe.”

➤ Edna, circa 1979. Courtesy of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum

Whoever she is—her namesake remains a mystery—Edna will be the queen of the museum’s Floating Fleet, joining a cast of fellow survivors back on the waters from which they came. Each year, she’ll be pulled up on land to receive “a shave and a haircut,” as they call her yearly maintenance, but she won’t be sitting in an exhibition hall, waiting for visitors, gathering dust. She’ll drop her lines from the St. Michaels dock and once again lift her sails along the Chesapeake. Starting with a six-month tour of neighboring ports next summer, she’ll be a working ship—no longer carrying oysters, but now the past, into the future—“a living witness,” as Kepner wrote, “as to how it was, once upon a time.”

Meanwhile, the crew is already on to other projects. Gorman will be crafting a racing log canoe out of those leftover loblolly pines, while Connor will be leading a new group of shipwrights, including many of Edna’s apprentices, in a recreation of the 17th-century Maryland Dove.

No one likes to put a number on it, but as the dreamer to Gorman’s cynic, Connor thinks the boat is going to last for a long, long time. He’s been told that every inch of hull gives a boat about a decade of life, which could mean at least another half-century for Edna. “As painstaking as it was to put her back together,” says Connor, “I’m still looking forward to seeing where she floats on her lines.”

Gorman, though, is going to leave the guessing up to the next guy. “God, I hope this doesn’t have to be done again for a while,” he says with a grin. “One hundred years would be nice.”