History & Politics

Lost and Found

Baltimore man connects long-lost vintage portraits and family photos with their loved ones.

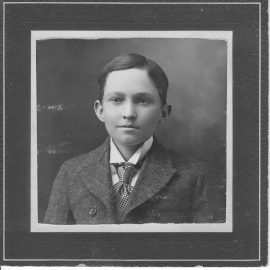

The first old photograph Chris Whitaker reunited with its family, he discovered in a Montana antique shop. The black-and-white picture is a coming-of-age portrait of a boy, attired in a wool suit, tie, and pressed, white, short-collared shirt in the style of the day—about 1890. His hair is parted, there’s a hint of a smile above his dimpled chin, and on the back of the photo someone long ago scrawled the boy’s name and hometown: Samuel Reynolds, Kingman, Kansas.

The few words on the back also described young Samuel as “my cousin.” The vacationing Whitaker decided to track down the boy’s family, searching census records and ancestry databases. A grateful descendant on Samuel’s family tree came across his research and blog, which included the picture of Samuel, and later drove across the country to the same store and unearthed more than 40 other lost family photographs. Whitaker was elated.

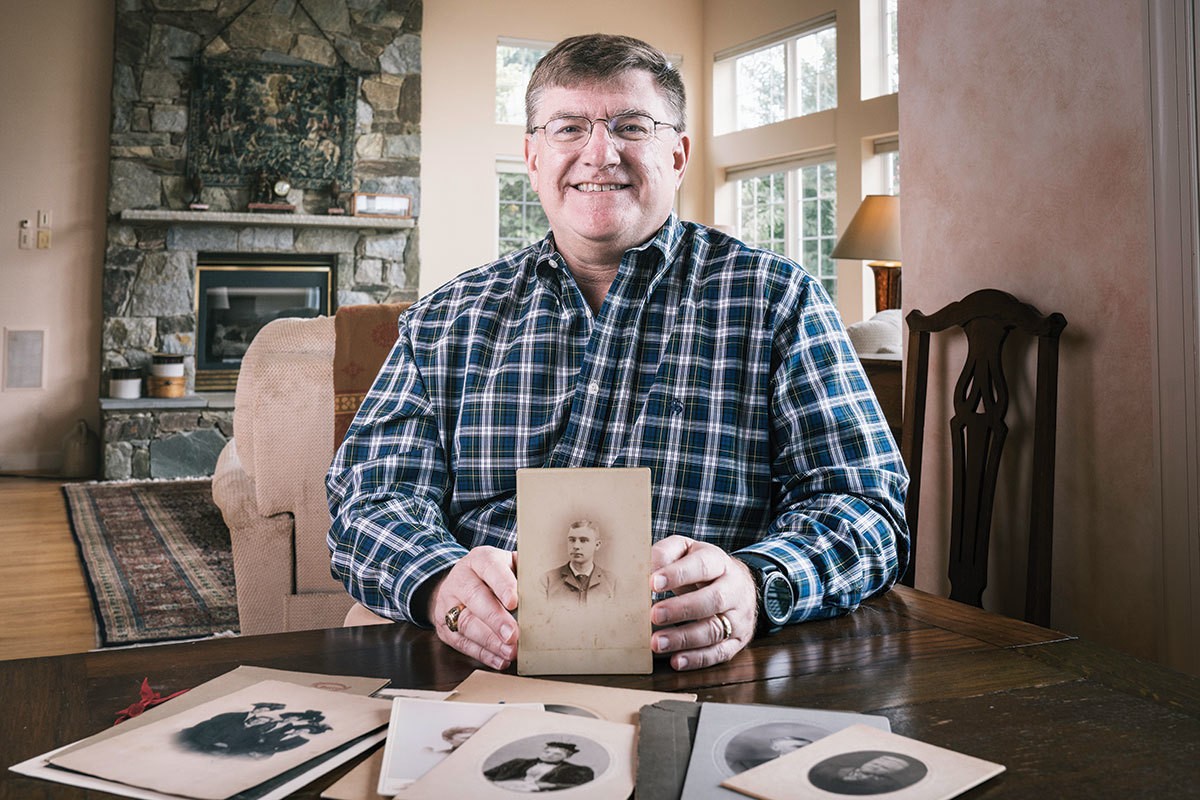

“I just thought if someone found a photograph of my great-grandfather, I’d be thrilled,” says Whitaker in his north Baltimore home office. “It was really that simple.”

Over the past three years, the retired Whitaker has fleshed out the identities of hundreds of wayward vintage portraits, most of which he has stumbled across in the dustbins of Hampden’s antique, book, and curio shops. Placing these mysteriously adrift portraits with their loved ones, at times, has proved difficult for unexpected reasons.

Shortly after his initial success with Samuel’s portrait, for example, Whitaker contacted the West Virginia daughter of a woman in a lovely 1940s portrait via Facebook. Not only did the woman not respond, she blocked him. “I think it creeped out the woman when I messaged her and I told her I had a picture of her mother,” Whitaker recalls with a laugh. Ever since, he just scans the photographs and posts them on his blog, including the subjects’ names and the location where he found the photo, encouraging people to email him if they discover an ancestor. “It’s rewarding,” he says. “And I like the detective work.”

In one case, Whitaker provided a woman in her 80s with the last photograph of her dad—taken four days before he was killed in a plane crash when she was a girl. He connected Reed Young to a youthful portrait of his grandfather, who died before the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory program manager was born.

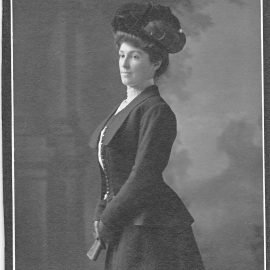

Whitaker’s found photos have taken him through time to the blocks of what was once “Little Bohemia” in East Baltimore, to the former stoop of former big-leaguer Edwin Americas Rommel, reportedly the first pitcher to deploy the knuckleball after the spitball’s banning in 1920. And to Fells Point, where a young wife named Ruth Collier sent photos of herself to her husband while he served in the South Pacific during World War II. (He returned home and the couple raised a family here.)

A Tennessee native, Whitaker became interested in genealogy in the mid-1980s when he couldn’t find pictures and found scant information about his maternal great-great-grandfather. He did, however, eventually locate his ancestor’s Civil War pension records at the National Archives. There, Whitaker read the firsthand account of the shot—from a Confederate rifle—that killed his great-great-grandfather at the Battle of Stones River.

Whitaker learned that his great-great-grandfather and both of his brothers had fled Tennessee after its secession to join Kentucky’s 9th Volunteers Infantry. All three gave their lives to the Union cause. “I don’t know if I fully absorbed their actions when I first came across that,” Whitaker says. “My appreciation, and pride in what they did, has continued to grow over the years.

“My younger brother, who is now deceased, and I grew up in Tennessee in the 1970s,” Whitaker continues, “when Confederate flags and Southern rock were all the rage and he gave me a lot of grief when I married my first wife because she was a Yankee from Philadelphia. [Learning about our great-great-grandfather] turned everything he believed on its head, which I thought was great.”