Arts & Culture

Cult Classic

John Waters shares highlights from his upcoming Baltimore Museum of Art retrospective.

No one better represents Baltimore’s fringe arts scene than living icon John Waters. From putting his hometown and its off-beat characters on the big screen in Hairspray to sparking the city’s affection for kitschy plastic flamingos and drag queen Divine in Pink Flamingos, his five-decade arts career continues to this day—and his eccentricity does, too.

On October 7, the Baltimore Museum of Art will unveil John Waters: Indecent Exposure, a retrospective of his work dating back to the 1990s, featuring more than 160 photos, video clips, early films, photocopied drawings, sculptures, and assorted ephemera (like archival photos of John with Andy Warhol and the framed Joan Miró reproduction he bought at the BMA Shop when he was a child). We asked him to reflect on some of his favorites from the upcoming salon-style exhibit.

You’ve lived in Baltimore all your life, you’ve been exhibiting in the U.S. and abroad for some 20 years—why are you just now doing this massive exhibit in your hometown?

I think it’s the right time for me to come home and have a show at the Baltimore Museum [of Art]. I couldn’t have the first one there because people would’ve just said, “Oh, that’s just because he lives in Baltimore.” I had to go out in the rest of the world and build 20 years of exhibitions and museum shows and books. Now that I’ve done that, I think Baltimore is the perfect homecoming. It’s where I got my first taste for the love of how art can infuriate people.

Baltimore is so prominent in all your films. It’s not obvious to a viewer whether it’s prominent in your visual art as well. Is it?

No. It’s the only thing I do that has very little to do with Baltimore. Not completely. My studio is there. My art assistants are there. I have a piece about Mr. Ray, who was one of the most notorious hairdo lunatics on the radio in Baltimore for decades, that I idolized—and he was horrified that I liked him [laughs].

What is it about Baltimore that’s kept you here?

Everything—the sense of humor and the extreme style. Everything I wrote about, everything that informed me was always about taking what some people think is a negative thing and exaggerating it, turning it into a style, and having a sense of humor about it. Baltimoreans have always done that. I like living there now more than I ever did because it’s the only place left that has a bohemia. It’s gotten more expensive, but it’s still cheaper than anywhere else. And kids can still live there and start, you know, bohemia! And the music scene there, the people who have had national success—they stayed. They bought houses. I think that’s very, very important, to stay in Baltimore.

You see that happening with the younger generations of artists?

Yes, I do. I see musicians and artists that grew up in Baltimore didn’t leave when they got success, and students that came here decided to stay. That’s all kind of new and good. You don’t have to leave Baltimore anymore to have success. You might have to have people outside of Baltimore like [your work], but you don’t have to leave.

So getting back to your exhibit—I understand that you take photos of TV screens and rearrange them to create a new narrative.

Yes, most of the work is like that. This show is really about editing. I take images from other people’s movies and put them in a completely different context, often with other movies and scenes, and tell a story that you read from left to write. So it’s about writing and editing.

All your career has been about that, right?

Yeah, you know, I write all my movies, I write all my books. I’ve never made a movie I didn’t write. This is just telling a story in a different way—in the art world rather than in a movie or onstage when I speak. It’s about telling a story and celebrating the failure of show business that really all the movie stills would be rejected from real publicity campaigns. They show what you can’t show.

I show the tape marks that the actors have to hit to stay in focus—but I don’t show the actors or costumes. I show things that go wrong like hair that gets stuck in the gate and ruins a scene. I just show everything that could go wrong and celebrate the failure of show business and the art world, hopefully in a humorous way, because I love everything I make fun.

Well and you’ve lived it—you’ve probably experienced firsthand pretty much everything that could go wrong on set.

Yes, I have, probably [laughs]. And I’ve experienced a lot that went right, too. And sometimes when something goes wrong, it is right in the arts world once it is isolated and put in a different completely showcase what is wrong is right. Like my commercially shot movies don’t work in the art world when I use them for imagery. The worst shot ones work the best.

So you’re using images from your movies as well other filmmakers’.

Once in a while, yes, but just one second of a movie—one second that proves no movies are bad. Because there’s 24 frames a second, and somehow you can find one frame out of 24 in a 90-minute movie that’s good.

Do you truly believe that no movie is bad?

I’m saying if you have access to every frame in a movie, no movie is all bad. You can find one great frame and celebrate it—out of context, stolen, isolated, hidden, put in the wrong projector, the wrong theater, the wrong book for the wrong audience, then it’s good.

I wanted to talk about this photograph called “Divine in Ecstasy.” What were you thinking when you captured that?

I was looking for a still that I didn’t have. I wanted that still. It’s the most ludicrous part of the film [Multiple Maniacs], where Divine is attacked and raped by a transgender man and an insane woman. It’s probably is the most sacrilegious scene to ever be filmed. I never had a still because we were always worried the police were gonna come and get us. We’d been arrested for making a movie before that, Mondo Trasho, so we’d jump out, do a scene, and run! So I just put an old VHS on the TV, and I just kept shooting like a crazed fan in the dark. And then I saw it and thought, oh God—this looks even artier than I could ever imagine. So that’s how I started doing this. Stills are what everyone remember from movies. I always knew how important they were. Even when I had no budget, I had stills.

Why is this photo considered your first official visual art piece?

I never say the word “art.” When people say to me, “I’m an artist,” I secretly think, “I’ll be the judge of that.” Someone else can call me an artist; I’m not calling myself an artist. I think that is up to others and history to call you an artist. But it was my first photograph that was ever shown in an art gallery.

Well, assuming what you’re exhibiting is art, do you see your work as pop art or conceptual art or what would you classify it as?

I think it is conceptual, if I had to name it. I think it all up before I do it. and then I have to go find the images to write with, to edit with, to make that concept come through. The whole idea behind the show is, can art be funny? It’s always been witty, but can it be funny? To me, it can be. But we’ll see.

John Picks His Favorites

Beverly Hills John. 2012. Rubell Family Collection, Miami. © John Waters, Courtesy Marianne Boesky Gallery

“I always say L.A. is just one big York Road. To me, eventually everyone is gonna look the same in L.A. There’s only so many kinds of faces you can get.”

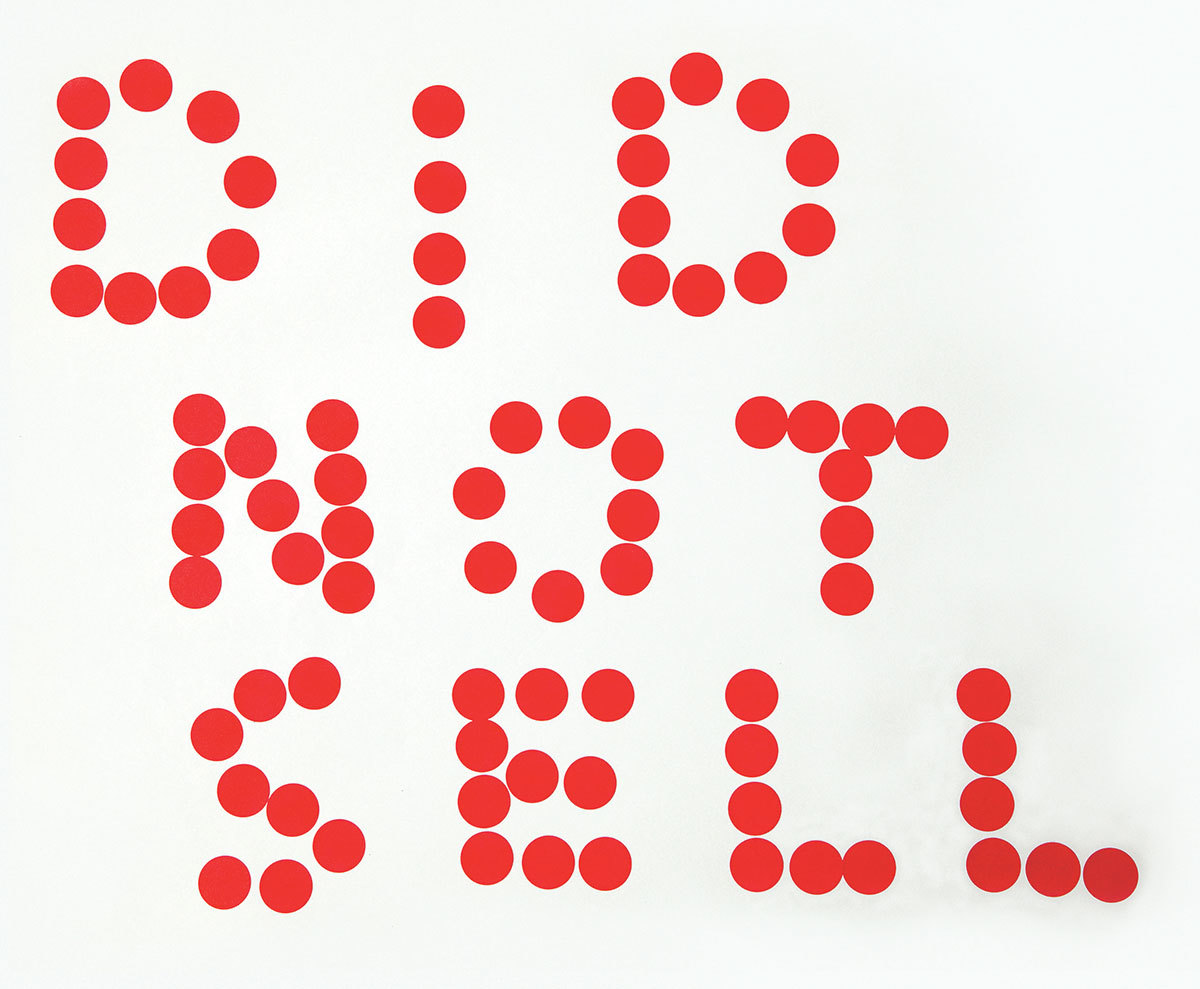

Congratulations. 2014. Collection of Brenda Richardson. © John Waters, Courtesy Marianne Boesky Gallery

“Congratulations is code. When your gallery calls you and says, ‘congratulations,’ you know that you sold something. When you’re a collector and you say, ‘I want it,’ the art dealer will say, ‘congratulations’—which to me is so ludicrous. Many galleries leave the price list out with red dots on [the pieces] when they’re sold. I told the story of the worst thing that can happen in the medium that is the best thing that can happen.”

Divine in Ecstasy. 1992. Collection of Amy and Zachary Lehman. © John Waters, Courtesy Marianne Boesky Gallery

“I wanted that still. It’s the most ludicrous part of the film [Multiple Maniacs], where Divine is attacked and raped by a transgender man and an insane woman. So I just put an old VHS on the TV, and I just kept shooting like a crazed fan in the dark. And then I saw it and thought, oh God——this looks even artier than I could ever imagine. So that’s how I started doing this. It was my first photograph that was ever shown in an art gallery.”

Loser Gift Basket. 2006. Courtesy of the Artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York. © John Waters

“I’m trying to imagine and celebrate everything that can go wrong in show business. Everybody used to give away gift baskets. If you went to the Oscars as a presenter, you’d get cars and stuff. You’d get amazing stuff. But then they started taxing you. It ruined—overnight—the gift bag business. This was my idea of what could be the worst gift basket if you lost the Oscars.”