Arts & Culture

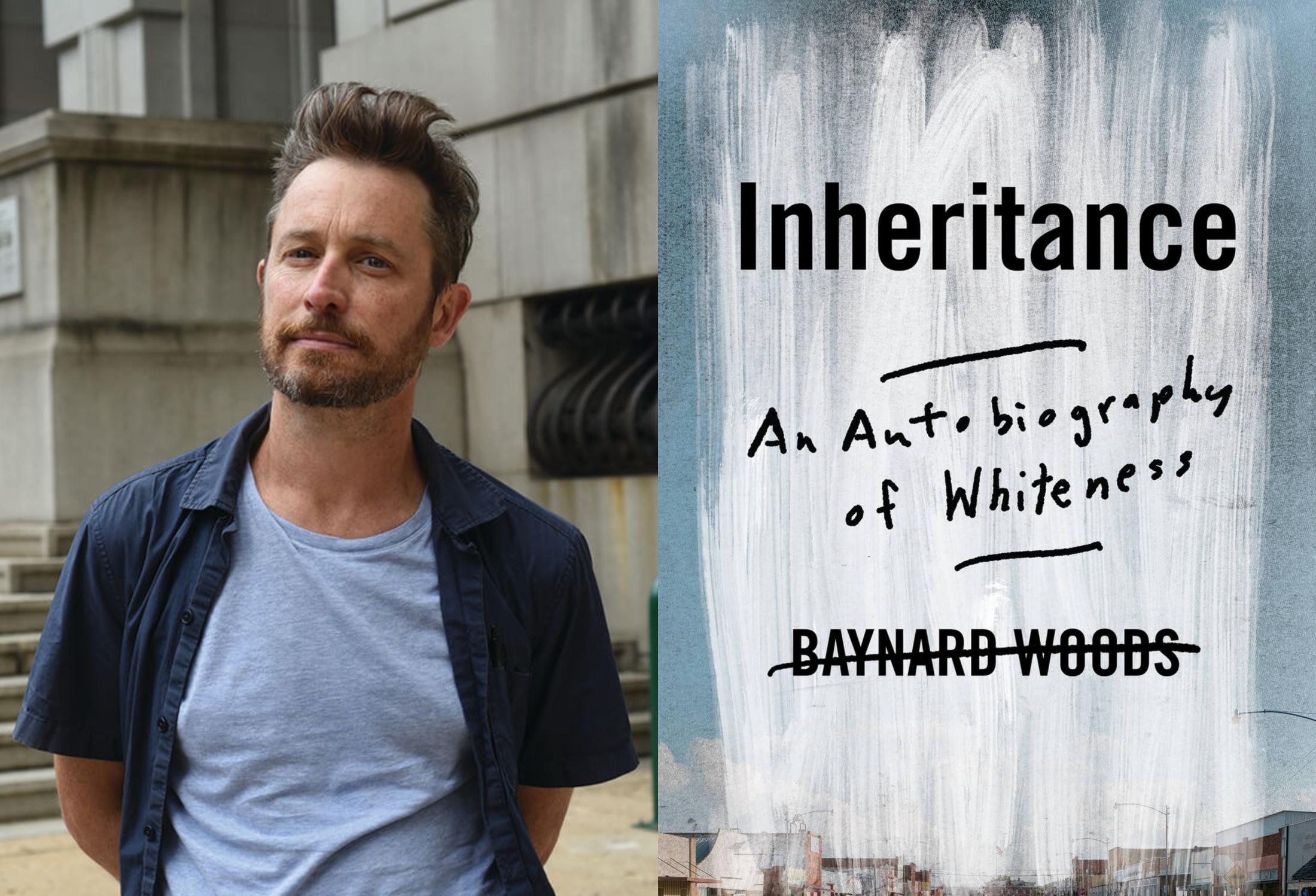

Baynard Woods Has Written Several Books, But Never One as Personal as His Latest

'Inheritance: An Autobiography of Whiteness' explores Woods' upbringing in the Deep South, as well as his family’s enslaver history.

Baltimore-based journalist and author Baynard Woods, a former City Paper editor, has written several books, among them Coffin Point: The Strange Cases of Ed McTeer, Witchdoctor Sheriff, and I Got a Monster: The Rise and Fall of America’s Most Corrupt Police Squad, co-authored by Brandon Soderberg. But he has never written one this personal.

His new book, Inheritance: An Autobiography of Whiteness, explores his upbringing in the Deep South, as well as his family’s enslaver history. Rather than assuming the role of a reporter investigating the embedded racism of his home state, with Inheritance, Woods examines his own experience in the white culture in which he was raised, and its invisibility to him. Woods is an engaging writer and aspects of his story will resonate with anyone who has grown up in the majority-white cities, towns, and suburbs of America. Especially those who struggle with the political dynamics of family get-togethers in the era of Donald Trump.

One thing that stuck with me was the quote about how laws are made to protect some people, but not bind them—and bind other people, but not protect them.

Yeah, I was horrified to realize how much of my own psychology had been sort of framed by the slave codes of 1740 in South Carolina, which set up these two systems of law whereby white people were protected and not bound—and Black people were bound, but not protected. And how often in my life, I had expected to be protected by the law without being bound by the law.

You covered the white supremacist rally in Charlottesville where Heather Heyer was killed. Does the effectiveness of the alt-right misinformation machine surprise you?

If you really trace the rise of Trump, and this is way before January 6, it just seems [you can go back to] the Lost Cause ideology as the progenitor of alternative facts. Think about how soon we first started hearing that phrase from the Trump Administration.

A major thread revolves around your great-grandfather, a Civil War veteran and state legislator, who was involved in the assassination of a Black man. And possibly, the rape of a young enslaved woman, with whom there is some evidence he may have had a child, or children.

I haven’t been able to pin it down for sure, but it wouldn’t have been unusual, to say the least. It was part of the economy. Rape enriched the rapist. There are Black families with the name Woods and McFadden [another family name]. With Ancestry.com and DNA, my uncle learned we have Black cousins in New York and several places, including Maryland.

Not being from the Deep South, it’s hard to get a feel for white culture there—the primacy of the Confederate flag, for instance—and the sense of aggrievement many white people experience there.

The civil rights movement was turbulent for white people. My parents, for example, grew up when every door they walked through was marked “white.” People have been filled with this either anger—for their privilege being taken away—or shame of having lived in an apartheid regime their entire life. I think that’s what Trump, Reagan, and so many others plugged into. My dad came of age right as the civil rights movement happened. This was an apartheid world that he had been raised to think was his right and it crumbled in front of him. And then it was just like, “Oh well, we’re just not going to talk about that anymore.” I think that did something psychologically to him.

You struggle with your father’s support for Donald Trump, especially toward the end when he’s dying from ALS.

Many times I liked him, and I always loved him. He had a lot of good qualities, and he had a lot of failings. I think that’s the question we have to deal with as white people. How do we deal with our family when they’re wrong? I see people saying, “If you’re white and you’re an ally, and you don’t talk to your family [about race], you’re not really an ally.” I don’t think that’s right. It’s not about purity or something like that. But I also don’t have a good answer, which is why I wrote the book. Eventually, I just played defense and quit trying to convince my dad.