Arts & Culture

David Bergman’s ‘Plain Sight’ is a Wake-Up Call to See the Wonder in Each Day

After being diagnosed with Parkinson’s, the retired Towson University English professor wrote his latest work of poetry—exploring new subject matter as he copes with aging and the evolving relationship with his body.

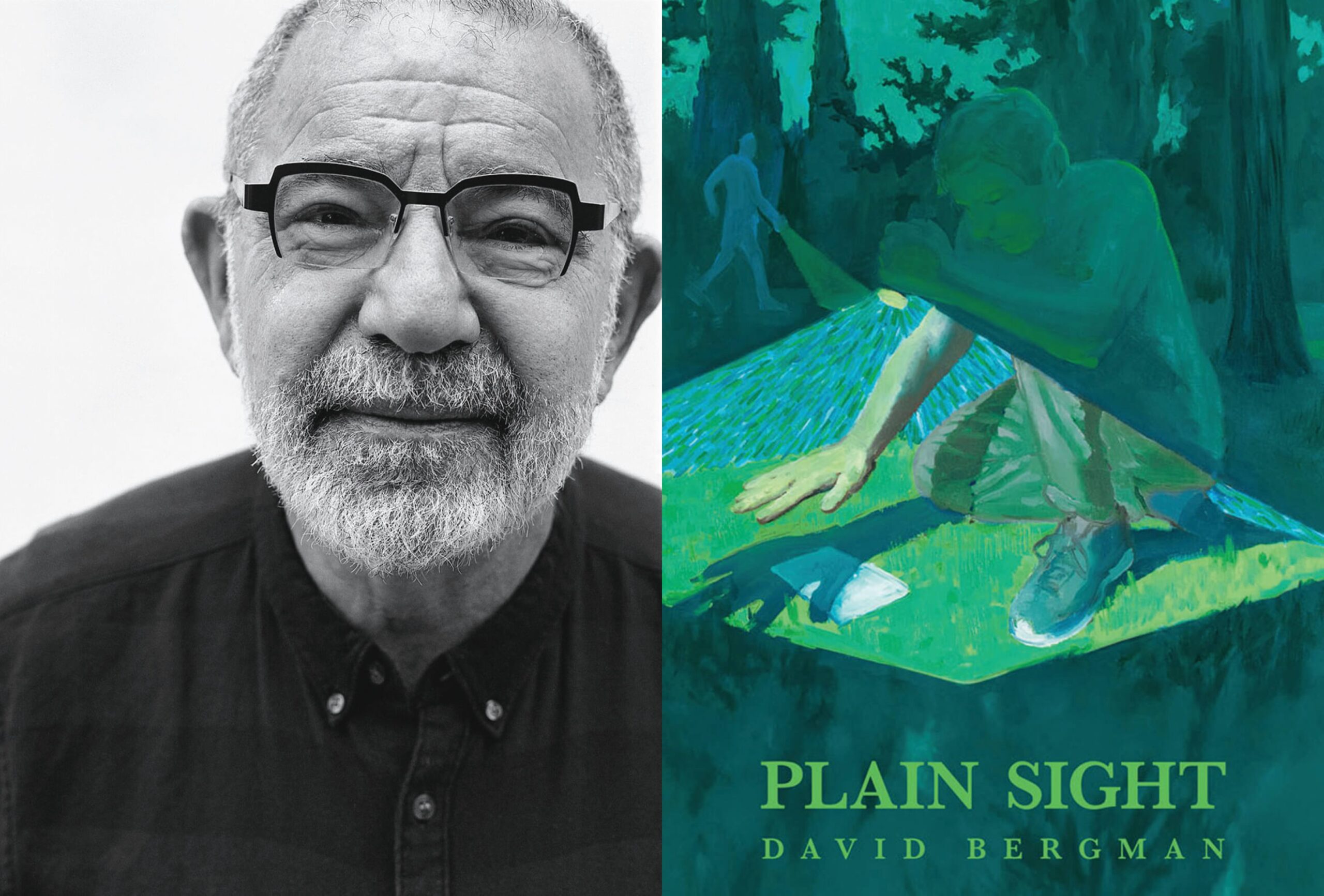

Writer and now-retired Towson University English professor David Bergman became a significant figure in gay literature decades ago. His first book, Cracking the Code, received the George Elliston Poetry Prize in 1985. Six years later, he published Gaiety Transfigured: Gay Self-Representation in American Literature, a seminal work of gay literary criticism. In 1998, as the deadliest years of the AIDS epidemic finally receded, he produced his second book of poetry, Heroic Measures. Subsequently, he and co-editor Karl Woelz won a Lambda Book Award for Men on Men 2000: Best Gay Fiction for the Millennium. Bergman’s third book-length work of poetry, Plain Sight, comes from Baltimore-based publisher Passenger.

Now 74, Bergman retired from teaching eight years ago, after being diagnosed with Parkinson’s. It was a combination of events that has provided him with time to write and new subject matter as he copes with aging and the evolving relationship with his body, which he does wryly and wistfully—and with a certain mordant humor. In whole, the observant stories in Plain Sight aren’t sad, but a wake-up call to see the wonder before us each day.

I love the title poem and the figurative use of in “plain sight” and what hides in plain sight—murder weapons, car keys—but mostly within ourselves. The last line is: “Look, I’ve been lost in plain sight for years, and no one has found me yet.”

Ha, yes. There’s nothing particularly plain about what’s in plain sight. There are writers who’ve been forgotten. I was thinking about me. Their books are on the shelves. They’re lost in plain sight. [The stories and characters in their books], they’re lost in plain sight.

It’s been 25 years since your last book-length work of poetry. Should we assume that these poems took time to germinate?

Well, I did have to wait, that’s true. But I wasn’t energetically pursuing getting a book published. There were so many more things happening in my life, like taking care of my parents and teaching, which took up an enormous amount of mental energy. I understand why writers were carpenters and farmers in the past. It’s not the same part of the mind working.

Obviously, Parkinson’s has changed your life. How has it changed your perspective as a poet?

I’m having trouble buttoning buttons because my fingers are not as sensitive as they were. Can I stretch the shape of the hole to make the buttons fit? Do I have to buy shirts with buttons that are easier to button? I begin to think about the whole problem of buttoning a button and that’s sort of amazing because even four years ago, I never would have thought about it. A small example. I’m working on a poem about becoming lightheaded, which sort of feels like going into a room that you recognize, but the furniture has been taken away. I also suffer from auditory hallucinations, a common side effect. There are allusions to that in the book. It’s fascinating how it functions. Sometimes I can stop them. Other times, it’s music that I hear, usually quite pleasant.

Much of the collection revolves around the engaging “The Man Who…”series. “TheManWho Hated Irony,” “The Man Approached by Dead Lovers,” etc. Some represent an aspect of your experiences. Not all, correct?

That’s right. “The Man Who” series began in one of my poetry writing classes [where the students] seemed emotionally closed in. I suggested they should write about themselves, but as a third person, and I wrote that poem in that class, too. I realized, “Oh, this might be a useful way of approaching some of the things that I want to talk about.” I’ve always loved psychological case studies, Freud, Kraft-Ebbing, Oliver Sacks, and these sort of became case studies. It opened up enormous possibilities for artistic speculation.

I also particularly admire the last poem, “Grace.” Perhaps because I recently had a high school reunion.

I went to a very small high school which closed soon after we graduated. Before our 50th year anniversary, one of the students contacted me via email and said, “Why don’t we get together for a high school reunion?” We’d never had one before and, in fact, there were only 22 members of the class. We were able to hunt down 20. Fifteen of them showed up and I didn’t remember ever being so warmly greeted. They extended grace—undeserved. I didn’t remember being that well-liked in high school. But, in retrospect, people seem to have liked me in school. It was nice. And I could extend grace in return. It was a nice feeling.