Arts & Culture

Q&A with Andrew Motion

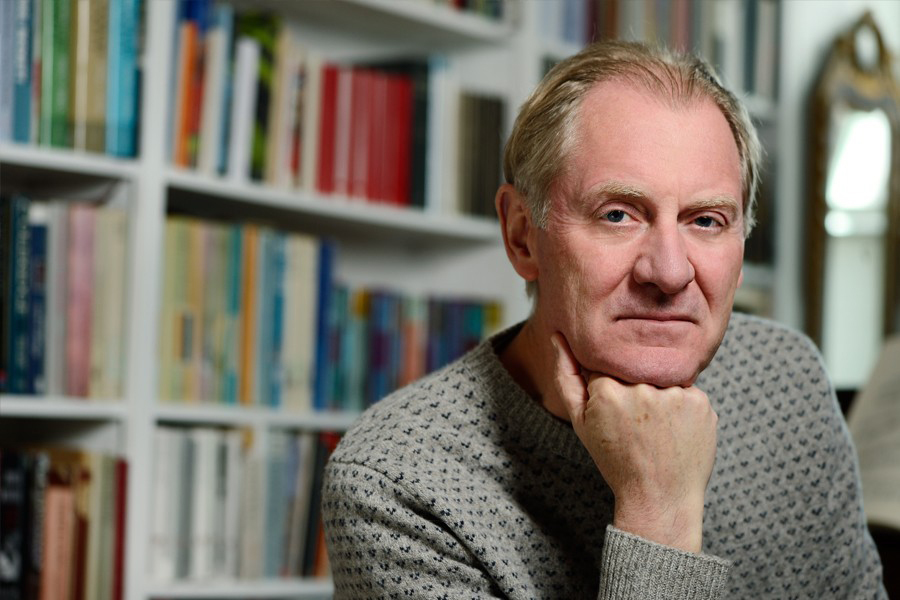

We talk to the poet laureate and Johns Hopkins University professor about his new life in Baltimore.

Andrew Motion’s lauded career precedes him. From 1999 to 2009, he was poet laureate of the United Kingdom, he won the coveted Ted Hughes Award in 2015, and was knighted for his contributions to poetry. But Motion left his home country two years ago to take a teaching position at The Johns Hopkins University, and now has released a new collection of poems, Coming In To Land, that spans his four-decade career. He joined us to talk about how he’s settling in, how Baltimore has affected his writing, and why salt-sprinkling lorries just appeared in a new poem.

You’ve lived here for two years now. How are you settling in to life in Baltimore?

I came here quite determinedly wanting to use the opportunity to write. It gives me a way to think about things in a more developed way than I did back in England, where I was much busier with other things. And if I were to live in New York, I think I would find it more difficult to get work done because there’s more going on, there are more distractions. So it suits me quite well to live a quieter life. I’m surprised by how pleased I am to be able to walk in a more or less straight line down the pavement. You can’t do that in New York because you’re constantly weaving in and out of other people, and that’s sort of true in London as well. It’s the right time to live more quietly and get more done.

What are your impressions of Johns Hopkins and the Writing Seminars?

The main thing is that I have very, very, very nice colleagues. I might say that, mightn’t I, but I really mean it. And I’ve worked in quite a lot of universities in my time, and I’ve never been in a department that’s as harmonious as this one. They’re usually a rat’s nest, but this one really isn’t. We all like each other, respect each other, and work well together. My students are very nice and clever and, as a whole, quite committed.

They haven’t read much, and I say this not dismissively of them at all—in fact I say this as sympathetically as I can. Because if they’re interested in reading, then, poor lambs, they ought to have been given the chance. I do feel critical of the system they came through that allowed them to read as little as they have. Which means that I sometimes find it quite difficult to know how to pitch what I’m saying. If it means that I can’t trust that everybody in the room has read “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” then that makes life more difficult than I’m used to it being. But what I can assume is if I tell them to go read it, they will, and they will say interesting things about it.

This is the first time you’ve taught poetry in the United States. How does your students’ work here differ from your students’ writing in the U.K.?

Their poems are not unlike the poems I’m used to seeing by my students back in the U.K., with the very interesting difference that American poetry in general is much more involved in identity politics as a sort of default setting than U.K. poetry is. And of course, it’s always interesting who someone thinks they are, but simply stating it isn’t enough. I spend a lot of time trying to get them to create a symbolic or metaphorical alternative, or a narrative at least that is not purely one that goes, “I did, I did, I did.” Because although that can be interesting, that can also be a bit narrow, I think, too finger wagging as well, too expository, not imaginatively seized enough. Not just to allow themselves to see what they are as part of a larger picture, but also to make it more like imaginative literature and less like true confessions.

Why do you think that is?

I think it has a lot to do with the race story here and the lack of harmonious integration between two or three major ethnic blocks. Which makes this a sad story fundamentally—people have to keep saying, “I’m this kind of person, and I matter. Think about my story.” There is a value in announcing yourself in that kind of way. But I’m a very dyed-in-the-wool Keatsian about these kinds of things, and this remark that Keats makes in one of his letters states, “We hate poetry that has a palpable design on us because it makes us put our minds in our books and walk away.” That’s something I’ve always believed very firmly. Of course, we need to announce our presence, but we need to do it in a way that it doesn’t make the reader feel as if they’re being read a lecture.

Do you have examples of American poets that you feel excel at that type of work?

I think the people who are doing it well find an interesting solution to this. Claudia Rankine, for instance, is an extremely interesting writer. I knew her before I came to the U.S. because she made a big splash [in the U.K.] as well. I’ve been reading her work quite closely and I find it extremely fascinating. Because she takes individual cases and her own individual case and connects it in very complicated ways to other things, and because she’s very good at saying what she means. Her thinking is sensuous, and that’s the kind of poetry that I like best.

How has being in Baltimore affected your work?

Two things happened when I got here. One is that I found myself writing a lot of things about my early days, about childhood and my parents. I’ve just finished writing a long poem about my brother, whom I’ve never written about before. It’s as though a plant of myself has been torn out of the ground and its roots are scrambling around, trying to grab on to something, and what they’re grabbing on to is past stuff.

It’s interesting that it took you coming here to do that.

It is. I’ve written a bit about childhood, but it’s gotten much more intense since I’ve come here. Now it’s about where do I come from? Who am I? And of course, I’m also focused on the here and now. But I think almost in principal I found that it would be presumptuous to think, “Right, I’m a poet and I’m going to write about Baltimore and I’m really going to tell what it’s like.” [Laughs] So I was a bit shy about it. It’s taken me a year or so to write about it in a direct way. I’ve just finished writing something about looking at things in Baltimore, it’s called “Surveillance.” It starts with a helicopter hovering over, looking at us. I thought how strange it must look to them, the light connecting the parts of the city. So it begins and ends with the helicopter and dots around places in the city.

How do you see your work evolving while you are here?

I expect I will write more about Baltimore in a recognizable way, but I don’t expect that I will make a fetish of it. Partly because I still feel that there would be some presumption in that, but also because I’ve never really wanted to write poems that were so precisely anchored in one place that they couldn’t be moved to another. I’m sure my next book of short poems will be full of references to Baltimore and Maryland. This morning, I wrote a poem thinking about the salt-sprinkling lorries. It’s set here, but what interested me is thinking about where the salt comes from, and it actually comes from under the Great Lakes. Four hundred million years ago, North America was about where Uganda is now, so the salt under the Great Lakes was laid down where Africa now is. And the idea of that salt being sprinkled on the streets of Baltimore, that’s an interesting thought. I feel a bit uncanny here. I feel very committed to the city and very committed to my teaching. There are people here with whom I’ve become very good friends and I feel loyal and invested. But I also feel a bit spectral. It’s not my place, it’s not my country, and there are millions of things I don’t understand. Like every writer, but perhaps like every transplanted writer, I feel at a sharp angle to everything.

This is such an interesting time in our country’s history for you to be here.

I thought Brexit was bad enough. Brexit is very bad, I think Brexit is actually worse because it’s forever and passionately keen to remain. I think it says something very vile about the majority of people in Britain, or in England, that they want to turn their back on the rest of Europe in this way. And as for the presidential election here, I think both it and Brexit are motivated by fear of the “other” and poor education. To think things are acceptable that have apparently been made acceptable by the election of Trump is only possible with people whose education has not been sufficiently developed. They are victims in that way.

The good news about Baltimore and its problems is that it knows it has got them. A lot of the difficult and/or repellant stuff in the U.K. it was in denial about it. Here, the city does know that there’s a problem, and only when you admit it can you then start to do something about it. And the good news about Trump is that in the worst case, provided that the world is still turning, he’s only president for eight years. American politics seems to vary precisely between one opposite to another opposite, so we might elect someone really cool next time.

Why did you decide to come out with this collection now?

To put it bluntly, I thought I’d ideally come to America and get a good publisher, and what should come first is a collection of poems. And that’s what happened, so I’m very pleased about it. I’m hoping what my British publisher publishes will be available in the U.S. as well. I’ve just given them a short something.

Sounds like you’ve been fairly prolific.

In England I used to get up and fight for time to write, which was hard to do because I’d committed myself to many different things. And when I was laureate there, especially, that seemed to me like the job—to do lots of talking and reading. And if it was the one morning a week when I got to write poems and didn’t work, I knew it would be a long time before I had another morning. Now, I have five mornings a week when I’m just writing, and if I have a bad day, it doesn’t matter because there’s tomorrow. That’s not only good for me in a practical way, but I think that’s allowed me to relax a bit and take some risks. And if my experiment doesn’t work, then what the hell, there’s always tomorrow. I’m very pleased about that, and I have written more than I expected.

This is the first year of my life when I can afford just to write poems. So God bless America.