Arts & Culture

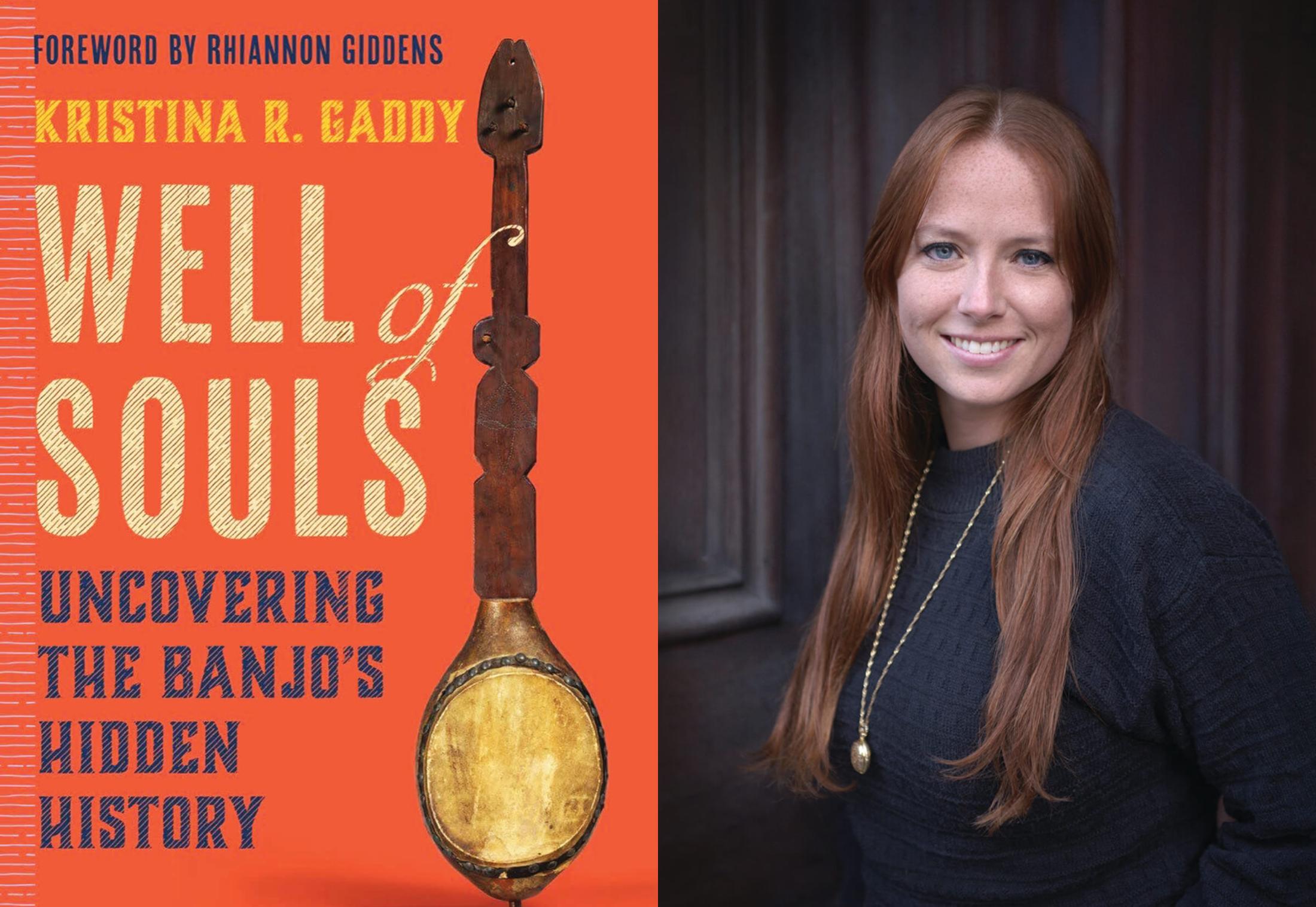

In New Book, Kristina R. Gaddy Tackles the Extraordinary History of the Banjo

'Well of Souls' will fascinate readers interested in early American music history—and just early American history, period.

Some authors stick to writing about one subject. Then there’s Kristina R. Gaddy.

The Baltimore-based writer and musician is the author of Flowers in the Gutter: The True Story of the Edelweiss Pirates, Teenagers Who Resisted the Nazis and now Well of Souls: Uncovering the Banjo’s Hidden History. She holds an M.F.A. in Nonfiction Writing from Goucher College. Her work has also appeared in The Washington Post, Washington City Paper, The Baltimore Sun, and Bitch magazine, among other publications (including this magazine). She is the recipient of the Parsons Award from the Library of Congress, a Logan Nonfiction Fellowship, and a Robert W. Deutsch Foundation Ruby’s artist award in support of Well of Souls.

With a deep interest in both forgotten history and the banjo—she previously produced a CD of field recordings from banjo player and ballad singer Currence Hammonds through the Augusta Heritage Center in Elkins, West Virginia—Gaddy tackles the instrument’s extraordinary journey from its African origins to the Caribbean, and, finally, to the U.S. Well researched and well-told through compelling stories of characters and places, including Maryland’s Eastern Shore, Well of Souls will fascinate readers interested in early American music history and just early American history, period.

By way of getting started, we should note you play the fiddle and the banjo.

I like to say that I’ve been learning a few tunes on the banjo for many years. I played classical violin growing up. [Since] my mom is from Sweden, and she plays music, I started playing Swedish folk music with her. My aunt is a bluegrass banjo player, so I learned some bluegrass stuff from her. But it was when I moved to West Virginia and lived in a house full of musicians and dancers that I began learning more fiddle, and the kind of American traditional music that we call old-time.

What got you interested in the history of this music?

Eventually, I came to learn about an older Black fiddler from Kensington, Maryland, where I grew up. He opened my eyes to the idea that we have this Appalachian music, but some of these traditions are much more widespread and much more diverse than we realize, because of the picture in our minds which comes with the various stereotypes we have with this kind of music.

Who was John Rose and why is he critical to the banjo story?

He lived in South Carolina in the 1700s and he painted what became an iconic watercolor of a dance in South Carolina. Until the early 2000s, he was actually not known, not identified as the painter, which was is kind of shocking because it had graced book covers and album covers. It was on the side of the Reginald F. Lewis Museum when they had an exhibit on slavery in the Chesapeake region, because even though it’s from South Carolina, we basically have no images of enslaved African Americans doing something that was not labor, but at their leisure. It is the earliest depiction of a banjo in North America, and it’s got a gourd body with a flat wooden neck. It doesn’t necessarily look like the banjos that we see today, but it matches all the contemporaneous descriptions of the instrument.

Was there a specific prompt for the book?

Basically, my partner and I came across a diorama, a three-dimensional work of art, in Amsterdam, that was made by an artist of African and European descent who lived his whole life in Suriname [on the northeast coast of South America]. It’s an identical scene to the old plantation in the watercolor painting, and as the book explains, it depicts a dance that is called the banjah, which is also an early word for banjo. I thought, “How is this related to the banjo?” and I went down a rabbit hole.

As you cover, by the mid-19th century, the banjo skips across cultures.

Blackface minstrels appropriate the instrument, and it becomes part of jazz, bluegrass, and country music. And that’s something a lot of folks don’t want to admit because the banjo has become so integral to so much music and culture in Appalachia and the South. They don’t want to say, “Oh, you know, it’s taken from this racist stage performance. That’s how we got our culture.” That’s harsh to say, but the reality is the banjo is also closely tied not only to African-American music and culture, but also to old African-American religious practices. That’s hard for some people to accept, who view it as part of white vernacular culture.