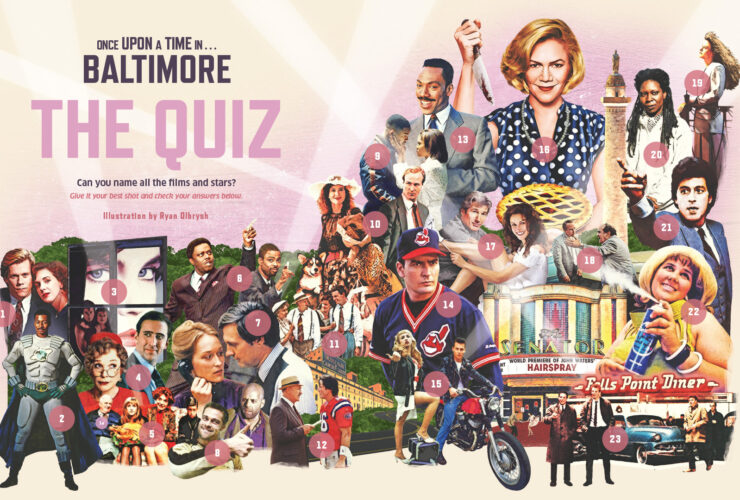

Arts & Culture

For the Record

The resurgence of vinyl culture is on full view at the Arbutus Record Show.

Chris Armbruster steers his 2011 RAV4 into the parking lot of the Arbutus Volunteer Fire Department and pulls to a stop near a set of double doors at the back of the building. It’s 6:30 on a cold and dark Sunday morning, but the early hour doesn’t faze him. Armbruster has been making this pre-dawn pilgrimage to Arbutus from his White Hall home for more than 20 years. The RAV4’s wheel-cover gives a clue as to why.

Chris Armbruster steers his 2011 RAV4 into the parking lot of the Arbutus Volunteer Fire Department and pulls to a stop near a set of double doors at the back of the building. It’s 6:30 on a cold and dark Sunday morning, but the early hour doesn’t faze him. Armbruster has been making this pre-dawn pilgrimage to Arbutus from his White Hall home for more than 20 years. The RAV4’s wheel-cover gives a clue as to why.

The customized cover’s meticulously rendered text is designed to catch the eyes of jazz aficionados. It looks startlingly similar to the front cover of Cannonball Adderley’s classic 1958 album Somethin’ Else, with the same color scheme, font, and background. It reads: “We pay cash for records and CDs. Jazz rock soul more. Call today. 410-627-6017.”

TALL STACK OF VINYL

A tiny line of text, near the bottom, signals just how serious Armbruster is about records. “Flat edge with gakubushi cover” will not mean much to most people, but to record collectors it indicates that this is a representation of a major find: these are markings—on the vinyl and jacket, respectively—that identify original, 1950s albums on the Blue Note jazz label, some of the rarest and most sought-after records in the world.

A U-Haul trailer hitched to the RAV4 is stuffed with some 3,000 records, which Armbruster begins unloading. Other vehicles packed with albums have arrived, and a small army of record-toting men and women stream in and out of the fire hall. The Arbutus Record Show, held the third Sunday of each month, opens to the public at 9 a.m. (Note: This month’s show is scheduled for May 27, the fourth Sunday.)

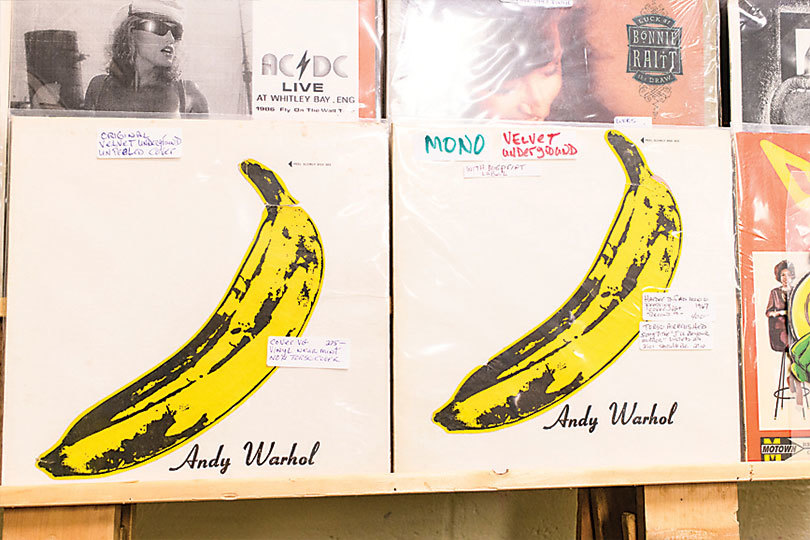

The dealers set out crates and boxes of records—with some CDs and assorted memorabilia in the mix—on tables arranged in rows stretching the length of the spacious room. Dealers pay $30 a table. Armbruster, who operated the Mount Vernon record shop Musical Exchange in the late ’90s and early-2000s, reserves four tables. He also sets up a display rack featuring a dozen of his priciest pieces, such as a test pressing of Tom Petty’s first album ($600) and a mint copy of The Velvet Underground and Nico with Andy Warhol’s iconic banana cover art intact ($500). He brought the Velvet Underground record hoping it might catch the eye of a particular customer he had in mind.

Armbruster says the most expensive record he’s ever sold at Arbutus was an original mono pressing of Sonny Rollins’ Saxophone Colossus—for $1,500. When asked if it’s difficult to part with such a rarity, Armbruster doesn’t hesitate: “As a dealer, it’s actually harder to look at a thousand-dollar record on your shelf and say, ‘I’ll keep that.’ No, you gotta pay your bills.”

Soon after the doors open, collectors flood the aisles. The customers skew male, but the wide range of ages is an indicator that vinyl’s resurgence may not be a fleeting trend. Armbruster sees evidence of exactly that, as millennials turn up looking for old records. “It’s almost like they’re curating a collection,” he says. “They’ll want a copy of Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours, along with jazz and soul and even classic country like Hank Williams and Johnny Cash.”

Armbruster pushes back the Notre Dame baseball cap he’s wearing and scans the crowded room. “Looking around, it seems like vinyl has definitely come back,” he says, “but for many people here, it never went away.”

The Armbruster's van. VELVET UNDERGROUND LPs. OLD 45 RECORD PLAYER.

Sales of new vinyl LPs grew for the 12th consecutive year in 2017. According to Nielsen, which tracks music and TV purchases, vinyl sales were up 9 percent last year to 14.3 million units sold. Legacy titles such as The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Bob Marley’s Legend sold particularly well, alongside more recent releases like Ed Sheeran’s (Divide).

In an era when consumers can stream all the music they want on pocket-sized devices, the resurgence of records, along with the old-school equipment needed to play them, may seem baffling. It makes sense to Armbruster: “Some people will opt for more of a high-quality experience over convenience.”

Cat Keyes is one of those people and attends the Arbutus show when her schedule allows. The 25-year-old Catonsville hairdresser doesn’t download or stream music on her phone, but she does have three turntables at home and a record collection heavy on 1980s New Wave and obscure film soundtracks. A lavishly packaged reissue of the Creepshow soundtrack—on colored vinyl with a comic book insert and extensive liner notes—is a particular favorite. “Albums like that are more immersive and interactive,” she says. “I have friends over for dinner parties, and they love going through my records and choosing something to play.”

David Koslowski, another Arbutus customer, concurs. “Vinyl is tangible and tactile, which can be particularly appealing to young people who’ve grown up listening to nothing but digital files,” he says. “Their world is so sped up, and putting on a record is also a good way to slow down and relax.”

Koslowski co-owns Baby’s On Fire (named after a Brian Eno song), a Mount Vernon café and record shop, with his wife, Shirlé Koslowski. When the couple opened the café two years ago, they figured that stocking records would add ambiance and allow customers to flip through bins of LPs while waiting for their orders. As it turns out, the vinyl has provided a bona fide revenue stream. “It’s even inspired some of our customers to buy turntables,” says David. “Now, they come in for coffee, a sandwich, and maybe a couple records.”

Besides indie music shops like Towson’s Record & Tape Traders, Catonsville’s Trax on Wax, The Sound Garden in Fells Point, and Normal’s in Waverly, records are now sold at Urban Outfitters, Barnes & Noble, and Target and online through Amazon, eBay, Popsike, Discogs, and other sites. A few vinyl delivery services have popped up around the country, like the Colorado-based Vinyl Me, Please, which mails select records to more than 30,000 subscribers who pay a monthly fee.

Record shows are thriving. Frank and Janet Ruehl, organizers of the Arbutus event, say the show often sells out vendor spaces, with dealers snapping up all of the hall’s 100-plus tables. Frank, now retired after 31 years working for Verizon, rents six tables for himself and four for his daughter, who also sells snappy T-shirts with “I found it! At the Arbutus Record Show” emblazoned across the back. “The shows have been good to us,” says Frank, noting that some dealers make the trip from New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia, and customers have come from as far as Japan. “We really enjoy the one-on-one relationships we’ve developed.”

Selling and buying online pales by comparison. At least, he imagines it does. “I’ve never sold one record on the internet, nor have I bought a record on the internet,” he says. “It wouldn’t be fun sitting in front of a computer screen, hitting a button, and it just comes in the mail. No, it’s all about the hunt, discovering the music, and meeting good people.”

Scenes from the Arbutus Record Show.

MISS FREDDIE

Quickley banters with dealers and customers, telling back-in-the-day stories about the likes of James Brown. As a teenager just out of high school, Quickley frequented the Royal Theatre, where she saw Brown, the Flamingos, the Drifters, and many other greats. On the night Brown recorded his live album Pure Dynamite at the Royal, Quickley was in the second row. “You can hear me screaming on that record.”

She often met the stars, got autographs, and ran errands for them. She’d dash across Pennsylvania Avenue to Mom’s restaurant and return with plates of food for performers, many of whom kept tabs at the restaurant. “I’d head out the door and Mom would be hollering, ‘You tell that James Brown to bring me my money,’” recalls Quickley, who can also dish on lesser-known personalities like “Cheese” Martin (Brown’s guitarist) and “Fat Daddy” Johnson (a popular DJ in the 1950s and ’60s).

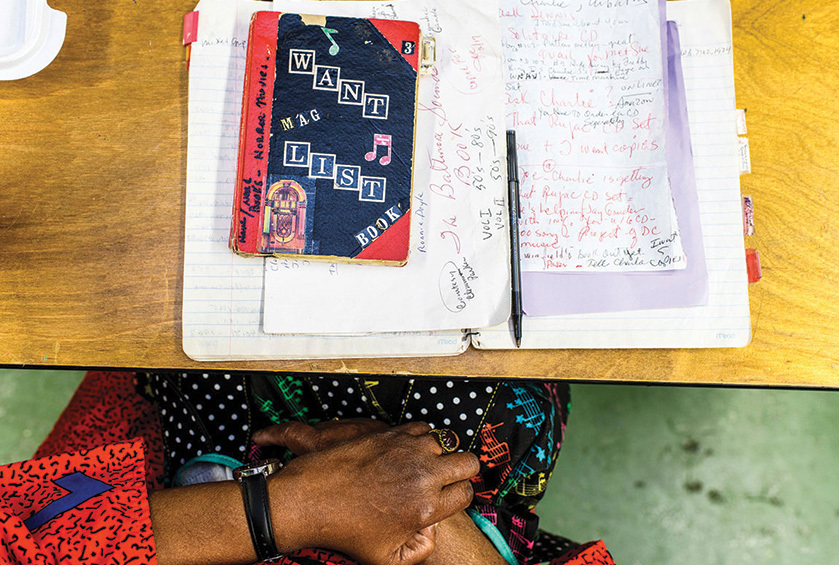

Quickley will share her stories with anyone who’s interested. “Some people come here for more than records,” she explains, “because it’s also about history and passing on what we know.”

Joe Vaccarino, also browsing at the show, literally wrote the book on Baltimore music. Vaccarino’s Baltimore Sounds is a history of local pop music from the 1950s to the 2000s, and he’s always hunting for regional rarities. He pulls a pair of choice 45s out of his bag and notes their significance: B.B. and the Oscars’ “Hold Me Tight” on Guilford Records (“issued by a recording studio that was located on Guilford Avenue”) and “You Bring Me Down” by The Royalettes (“a vocal group named after the Royal Theatre”).

“it’s all about the hunt, discovering the music, and meeting good people.”

Catherine Bailey rents a table every few months and sells mostly jazz, soul, and political speeches by Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X. It’s an idiosyncratic collection, one that would seem to have a story behind it. Sure enough, they were collected by Bailey’s deceased brother, Jan, who worked as a civil rights activist in the late 1960s, and she’s happy to reminisce about the era. “I come to talk and socialize more than anything else,” she says.

It’s an important aspect of the show, demonstrating how the LPs exert a near-totemic pull that bends toward recognition, acceptance, and, ultimately, camaraderie. They spark conversations and get total strangers swapping stories about concerts, record stores, and favorite tunes. Walking through the hall and overhearing snippets of chatter is like listening to an oral history mixtape of music memories.

“Man, I miss the Record Bar in Glen Burnie.”

“I just spotted a copy of Shaun Cassidy’s Da Doo Ron Ron, the first record I ever owned.”

“I saw The Supremes at the ballroom on the steel pier in Atlantic City. They wore those green-ish formal dresses, which made them look like bridesmaids, with gloves.”

SHOW ORGANIZERS Frank and Janet Ruehl.

Jack Skutnick, a dealer from Binghamton, New York, views the scene through something of an egalitarian lens. “Nobody looks down on anyone here,” says Skutnick. “If you want to listen to Lawrence Welk, that’s great. We aren’t snobs. I used to sell antiques, and that attracts snobby people, which wasn’t any fun. This is fun.

“Look around this show and what do you see? You see happy people.”

For hours, they mingle and meander. While some folks come early to strike deals or nab the rarest of rarities, others consider potential purchases for hours. Roger Priode, who made the drive from Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, had his eye on a $22 Molly Hatchet Flirtin’ with Disaster picture disc for most of the day and eventually got it for $15. Someone has offered to buy the Ozzy Osbourne T-shirt right off Priode’s back, which, he says, “wouldn’t be the first time.” If he can get $30 for the shirt, he hopes to buy another picture disc.

As morning gives way to afternoon and the crowd thins, Armbruster is pleased. Business has been brisk, and the customer he had in mind for the Velvet Underground record did, indeed, buy it. “Some people who come here might spend a good portion of their paychecks,” says Armbruster, “while others spend just a few dollars. But everybody leaves with something that makes them feel good.”