Fall Arts

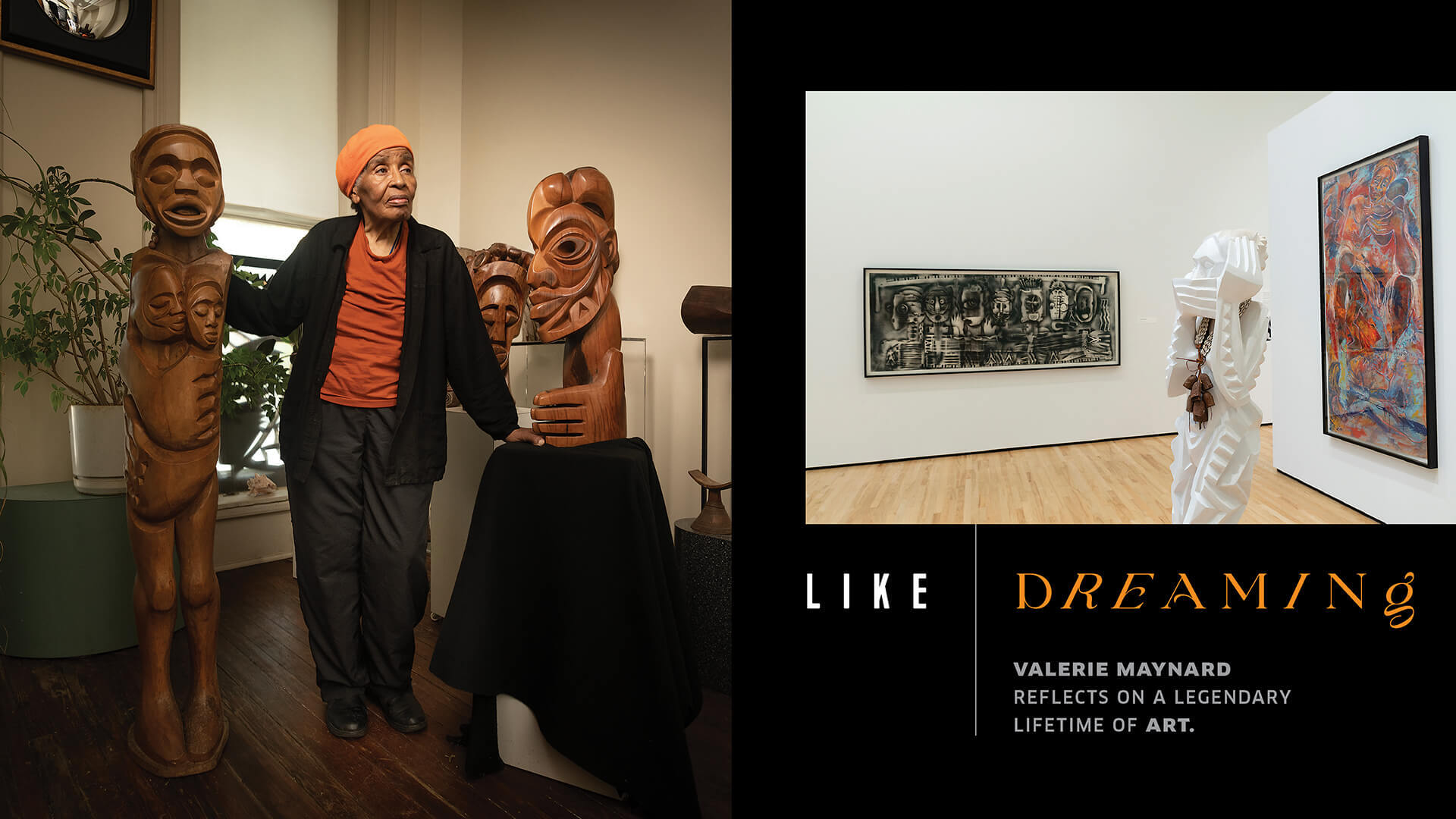

Like Dreaming

Valerie Maynard reflects on a legendary lifetime of art.

Editor's Note 9/20/22: Sadly, Valerie Maynard passed away earlier this week. We're honored to share this intimate profile from our September 2022 issue in acknowledgement of her incredible life and legacy.

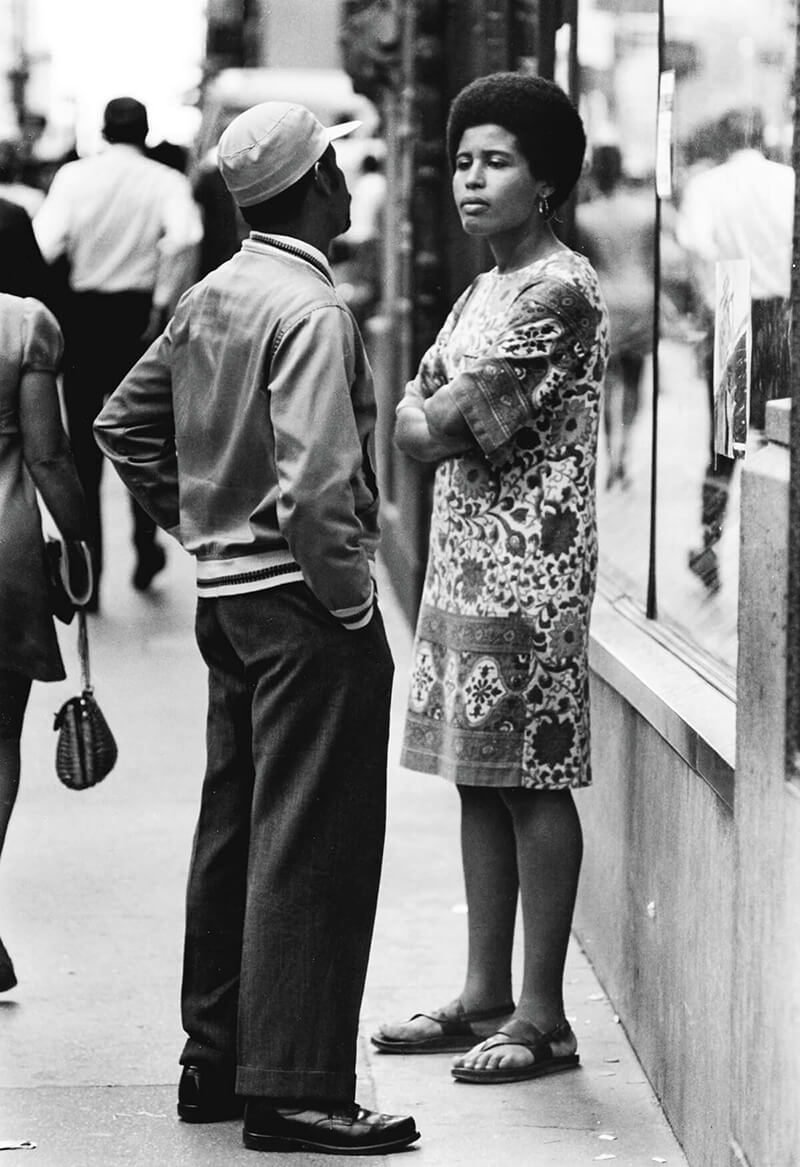

The artist in The Studio Museum in Harlem, 1971. COURTESY OF THE STUDIO MUSEUM IN HARLEM ARCHIVES/PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN.

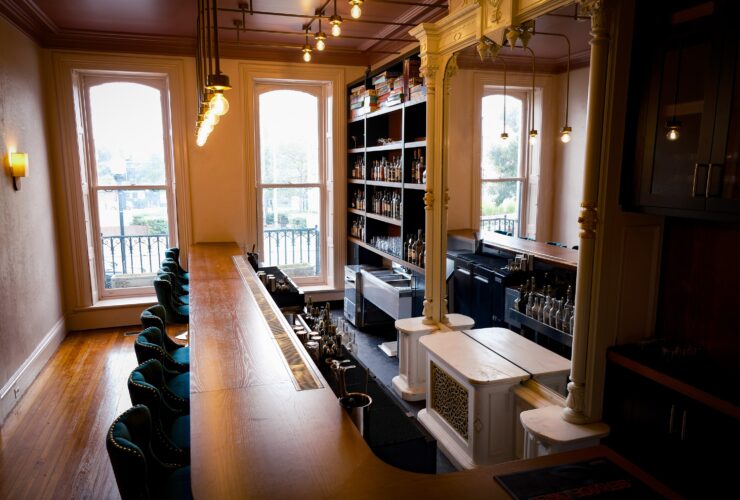

Valerie Maynard surveys the front room of her Station North rowhome, looking over an array of sculptures on pedestals, framed prints leaning against walls, paintings on rolls of paper, and metal pieces set in the windows.

The space functions as an ad hoc gallery of her art over the past six decades. The work is so varied in style, scale, and medium, it’s hard to believe it’s the output of a single artist. But for Maynard, a significant figure of the pioneering Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and ’70s, it’s also testament to an undaunted creative spirit.

Walking around the room, the 85-year-old artist seems genuinely astonished at having produced such a variety of work. She speaks softly, but authoritatively. Her pronunciation of New York as “New Yawk” hints that she isn’t originally from Baltimore. White hair peeks around the edges of a plum-colored beret; silver bracelets and a “Keep Hope Alive” wristband poke beyond the sleeves of her purple turtleneck. “I was never a driven artist,” she says. “I know people who get up and work at it all day. I was never that way. I never saw myself on a pedestal.”

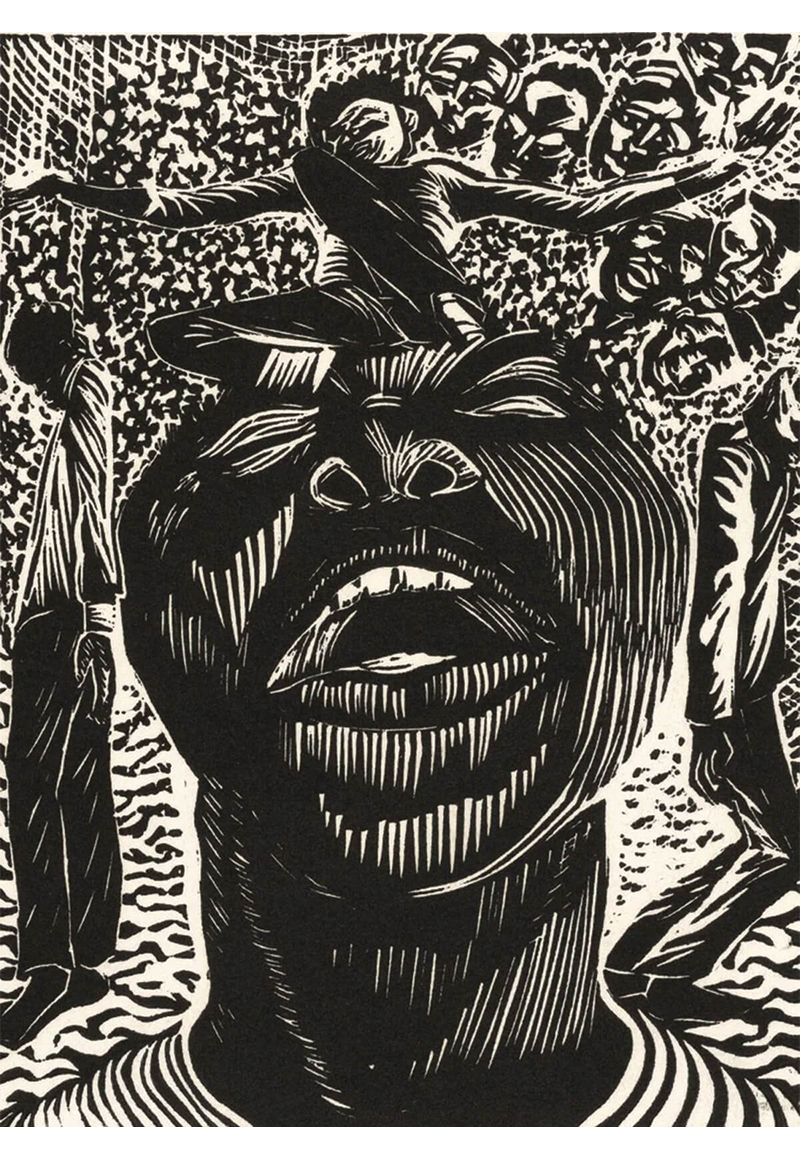

Maynard approaches a large head chiseled from a block of wood, lays a hand on each side of the face, and pauses a moment. The head’s wide eyes convey a sense of seen-it-all compassion, or fatigue; the open mouth suggests truths to be told. She turns the piece around to reveal the carved figure of a distraught man behind bars, a tribute to her older brother, Tony, who, for a period of time, went to prison for a murder he didn’t commit.

She says Tony had many advocates, including her longtime friend “Jimmy”—yes, that’s James Baldwin. Baldwin reportedly used Tony’s case as inspiration for the novel If Beale Street Could Talk and may have nodded to Valerie by making his protagonist, Fonny, a sculptor. A couple of Maynard’s sculptures were used in Barry Jenkins’ 2018 film adaptation of the book.

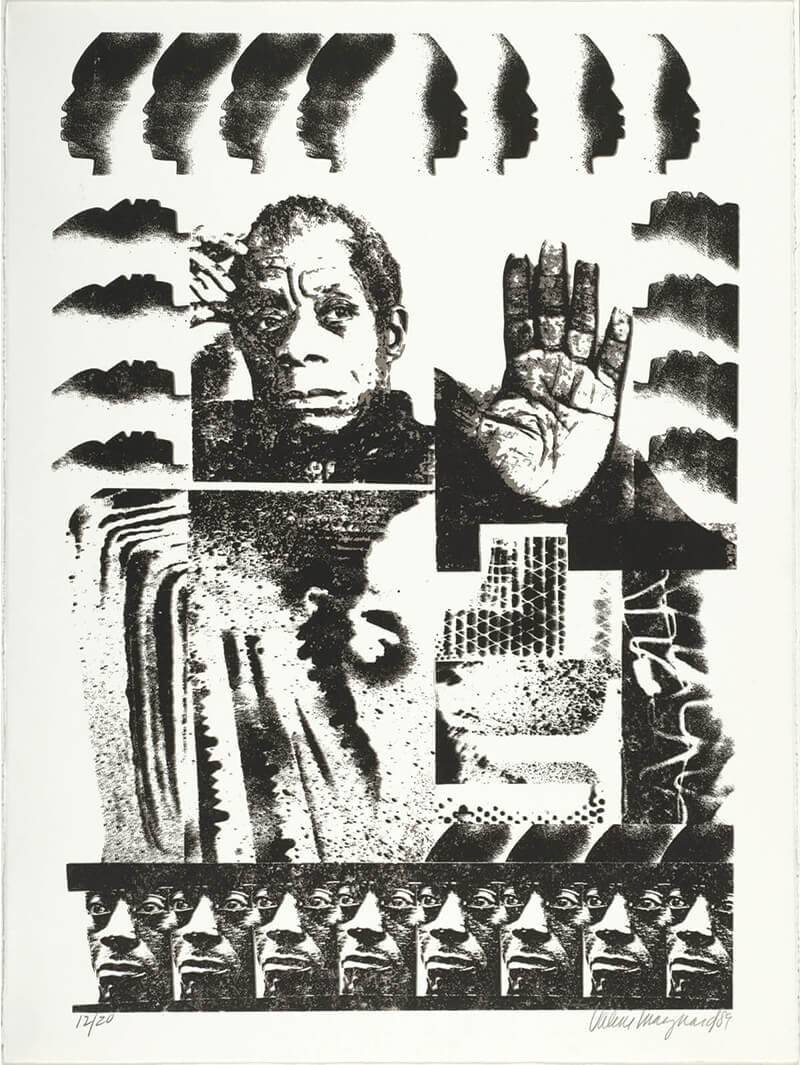

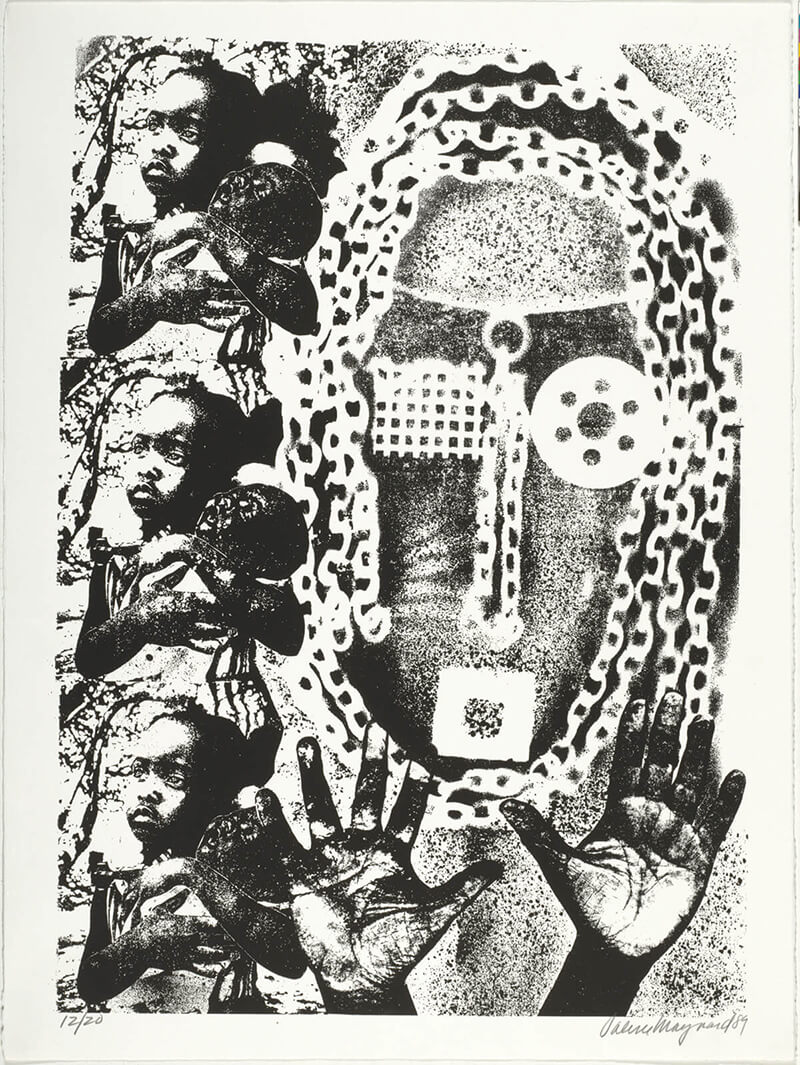

Maynard claims she never deliberately chose civil rights as an artistic subject matter—she simply observed what was happening around her and hated seeing people take advantage of others. She pulls out a pair of framed prints akin to her Lost and Found and No Apartheid series that were exhibited at the Baltimore Museum of Art in 2020. That first series—haunting black-and-white prints that are so affecting they resist being reduced to mere politics—included a frontispiece by iconic novelist Toni Morrison, whom Maynard calls “a great spirit.”

“This is art that summons, that creates what should be and disassembles what should not,” wrote Morrison. “The medium is dream, but the power is magic.”

Maynard turns to an untitled sculpture in the middle of the room. Its centrality suggests it holds special significance. Still partially crated after being returned from the BMA, the striking figure is painted white and stands six feet tall. A beaded necklace of cowry shells and bells made from seedpods spills from its chest. Maynard points out the large hand covering the entire mouth. “Sometimes, we don’t have words for what we see, or where we find ourselves,” she says.

Maynard fingers the necklace and looks into the face that she chiseled decades ago. “I guess it’s like dreaming,” she says. “If you just stay still, it will come through.”

Top left, “Rufus,” 1968; top right and bottom left,

“Untitled,” from the 'Lost and Found' series, 1989; bottom right,

a pair of sculptures at Maynard’s home. Courtesy of the Baltimore Museum of Art/Photography by Mitro Hood (3); Wood Carvings (Bottom, Right): Photography by Mike Morgan

L ike her accent suggests, Maynard grew up in Harlem. Her parents met as teenagers, when her mother came from Miami to visit family in New York. Her father was smitten and, hoping to make an impression, built a bicycle out of wood to ride her around the neighborhood. They married 18 months later and had three children—Valerie was the middle child. To support his young family, her father worked various jobs: as a Central Park security guard during World War II, loading and unloading cargo at the city docks, and tending bar at night. Her mother, Maynard recalls, played the piano and exuded sensitivity and a deep sense of consciousness.

Maynard likens the Harlem of her youth to a village, albeit one populated with cultural icons. She lived on 142nd Street near the Savoy Ballroom and watched jazz greats like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie come and go, often hearing the musicians rehearsing before show time. The family attended Sunday services at the nearby Abyssinian Baptist Church, which was well known for its charismatic preacher, Adam Clayton Powell Jr., as well as its focus on social justice issues. The poet Audre Lorde and her sisters lived next door to the Maynards. Those familiar presences made a lasting impression on Valerie.

“You just saw these people as neighbors,” she says. “Oh, that’s Langston Hughes over there. The fame didn’t mean anything to us. It wasn’t until I was older and looking back that I saw the enormity of it.”

Maynard was especially close to the Baldwin family, pointing to a photo of James collaged into a Lost and Found print. “I went to school with one of his sisters and spent many hours just sitting and talking with him and his mother,” she says. Later, she visited the writer at his home in the south of France. “Thank goodness for him, in so many ways. I won’t even say anything about intellect, because it was more about the vastness of his spirit.”

While in New York, Maynard also frequented the city’s sprawling public library system, especially the nearby Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, which housed an extensive collection of materials relating to African and African-American culture. Bashful and quiet, she became a voracious reader, and books piqued her curiosity and expanded her worldview.

Piles of books around her house indicate that’s still the case, though Maynard swears she doesn’t read as much as she used to. One stack includes June Jordan’s Civil Wars, Isabel Allende’s The Japanese Lover, Anne Terry White’s Lost Worlds, and Granta’s “Women and Children First” issue.

Atop the stack sits a wooden sign that reads “Walking: It’s Good for the Sole.” It alludes to Maynard’s preferred mode of transit and her love of the outdoors. She relished exploring New York on foot, accompanied by friends or siblings. “We walked the five boroughs and back,” she says. “If I went across the bridge, I’d be in the Bronx, I could be in Brooklyn. I loved going to the Museum of Natural History. We walked everywhere.”

Her introduction to art was similarly informal. She “liked to make stuff,” as she puts it, at school and summer camp and, as a teenager, took drawing and painting classes at The Museum of Modern Art on Saturdays. Her creativity flourished and, though she produced lifelike pictures and worked for a time as assistant to a portraitist, she found that style limiting and, ultimately, uninspiring. “I knew I didn’t want to do work where someone would be telling me, ‘Don’t do that because my eye is funny over here,’ or ‘That doesn’t look like my nose.’ I knew I wasn’t going to do that,” she says.

Maynard’s artistic career has not unfolded in a linear fashion. In fact, she would likely object to the word “career” being associated with her art-making at all. Though she studied art at The New School in Manhattan and Vermont’s Goddard College, Maynard doesn’t point to a mentor or professor who significantly influenced her process. At the suggestion that she’s mostly self-taught, she declares, “Oh, definitely.”

To further the point, Maynard describes her first attempt at stone carving. It was 1968, and she was working at a summer camp in Brattleboro, Vermont. With some free time, she went to the local swimming hole, swung out on a rope swing, and splashed into the water. “Bam, I go down and see this stone on the bottom,” she recalls. “I went back later and brought it up, but I didn’t know what I was going to do with it, because I hadn’t done anything like that.”

Maynard working on the City College bas-relief murals. Courtesy Of Valerie Maynard/photographer Unknown.

In her studio, Maynard tilted the stone on its side, envisioned a face in the rock, and got started. She opted for hand tools over electric, she says, “for a more intimate kind of creating,” and remembers very little about the trance-like work that followed. “One day, there he was,” she says of the stone head she named Rufus. “I had carved it, just like I knew what I was doing.”

Back in New York, she took an interest in printmaking and established a workshop at the Studio Museum in Harlem. It was the late 1960s, the Black Arts Movement—propelled by activist-artists such as Baldwin and poet Amiri Baraka—was in full swing, and as an artist-in-residence, Maynard became known for Afro-centric linocuts. In 1970, she showed her work for the first time at the museum.

Experimentation with different methods and materials would follow—using spray paint and found materials to make prints, for instance, and carving bolder, more evocative sculptures. From the outset, she tackled human rights issues with a keen eye for personal struggles buoyed by a yearning for transcendence.

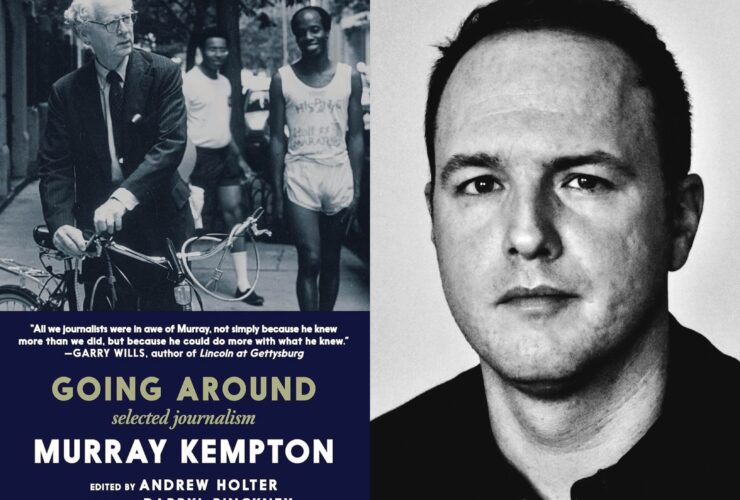

Wider recognition came gradually. Though never as wellknown as, say, Elizabeth Catlett or Romare Bearden, Maynard started turning up in books such as Creating Their Own Image: The History of African-American Women Artists (Oxford University Press) and Bearing Witness: Contemporary Works by African American Women Artists (Rizzoli International). Over the years, she exhibited at venues such as Manhattan’s Just Above Midtown Gallery, The Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, Texas, and overseas in Stockholm, Sweden, and Lagos, Nigeria. The Brooklyn Museum, the Library of Congress, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology all acquired her work, as did notable artists such as Stevie Wonder, Lena Horne, and Toni Morrison. The BMA recently added more than a dozen Maynard artworks, including “Rufus,” to its collection, and a selection of her linocuts will be exhibited as part of a new MoMA exhibition that opens October 9.

“Her art mirrors the struggles of African Americans and reflects the complexities of her identity,” says Asma Naeem, co-curator of the BMA’s Lost and Found exhibition. “It’s been a lifelong commitment of hers.”

Such a diverse assortment of venues hints at the wide-ranging relevance of Maynard’s art. Bill Gaskins, a professor at Maryland Institute College of Art, noted exactly that in an essay for the BMA’s exhibition catalogue. “Despite the historical, political, racial, and gender-specific forces in the life of the artist,” wrote Gaskins, “Maynard’s work excludes no one who has ever been in love (or wanted to be), sought justice, or recognized injustice. Her work excludes no one who ever shared a moment with a parent, grandparent, or guardian, sibling or child, or God.”

That sort of universality, what Maynard calls “humanbeingness,” is likely why she has been commissioned for large-scale public artworks for so many to see: glass and ceramic mosaics for a New York subway stop, a steel monument in Boston’s Ramsey Park, a granite frieze at a Brooklyn school, aluminum sculptures at a New Jersey train station, and a pair of murals for the auditorium at Baltimore City College.

Maynard in front of her Station North home. “Strange Fruit,” linocut; The artist on a street in Harlem, 1969. Mike Morgan; Courtesy Of Valerie Maynard; © Chester Higgins. All Rights Reserved.

Arts & Culture

These Are The Fall Arts Events You Can’t Miss in Baltimore This Season

The city's renowned art scene is thriving. Here are the chatter-worthy performances and exhibits to mark on your calendar.

W hich brings us back to Baltimore. In the late 1970s, the City College commission brought Maynard to the city. She recalls getting “no directive” on the murals and was free to create whatever she wanted. Perhaps not surprisingly, she opted for something she’d never attempted before: wooden bas-relief carvings, 14 feet high and eight feet wide.

The murals bring to mind her linocut work, but larger than life, with vibrant compositions of intermingling faces and figures. “I called them ‘folk people,’ because they would be seen by all kinds of different people,” she says of the carved figures, which have been in place for 42 years.

After teaching sculpture and printmaking at Howard University, Maynard came to the Baltimore School for the Arts in 1980, soon after it opened its doors on Cathedral Street, where she founded the school’s sculpture program. “I made a sculpture studio on the first floor, sent for some tools, and got started,” she recalls. When asked what wisdom she shared with her students, she chuckles and quips: “Don’t cut yourself. And be on time.”

Turning serious, she reiterates her belief in the importance of following intuition and forging your own path. “I just wanted them to be serious and imbue their spirit in their work,” she says. “That spirit is whatever comes through you. Somehow, you are not in control. We have titles like ‘Master’ this and ‘Master’ that, but making art is nothing like that. It’s a humbling experience.”

It brings to mind something Maynard once told artist Howardena Pindell during a Q&A: “When we ask people to study other people, or movements, or techniques, they’re being pulled away [from themselves], and the essence of them is just sitting there, tapping its foot, saying, ‘When you coming over here?’” she said. “I think it can be a distraction. Take time to mature and really get to know how you feel, how you think. Each one of us is unique. I think the world should get that, and not spend time being the observer to a screen or looking at someone else’s life.”

Her advice? “Jump in—live in the world.”

In 2006, Maynard jumped at the chance to purchase her Station North home. She had been living in a small East Baltimore rowhouse but had her eye on “the little bank building” at the corner of North and Maryland Avenues. That is, until she spotted a group of houses, similar to Harlem’s brownstones, near the bank. One of them happened to be owned by a dentist closing his practice, and Maynard bought the building from him.

When asked about her impressions of Baltimore, Maynard doesn’t immediately answer. “It’s not an easy question,” she says, but mentions the city’s slower pace compared to New York and easy access to parks, because she still enjoys the outdoors.

“Mourning for Maurice,” 1970 from the 2020 BMA exhibition; Portrait of the artist, c. 1980; “Gary Bartz at the East,” woodcut. Photographer Unknown; Courtesy Of The Baltimore Museum Of Art/photography By Mitro Hood; Courtesy Of Valerie Maynard.

“What Can I Do About All of

this Injustice,” linocut. Courtesy Of Valerie Maynard

Locally, she remains a well-kept secret for an artist of her stature, though both New Door Creative and Galerie Myrtis have shown her work over the years. In 2020, the BMA’s Lost and Found exhibition of Maynard’s prints, sculptures, and paintings—her first major museum exhibition—seemed poised to up her profile.

“Valerie is low-key and not a flashy art market person,” notes the BMA’s Naeem. “We wanted to make sure that an artist of her importance, living just a few blocks [from the BMA], got the recognition she deserves.”

Unfortunately, the BMA exhibition coincided with the first wave of the coronavirus, and most people were unable to see it in-person. Similarly, MICA honored Maynard with an honorary degree at commencement last year, but it, too, was waylaid by COVID-19 and limited to being a mostly virtual event. But Maynard has nonetheless managed to inspire and connect with younger, in-the-know artists around town.

“She serves as a mentor to so many of us,” noted local artist and writer Angela N. Carroll during a BMA gallery talk shared on YouTube. “She serves as a model for all of the possibilities that can happen when you’re dedicated . . . to community through your art.”

Photographer SHAN Wallace met Maynard six years ago. Wallace has a studio at the Motor House near Maynard’s home and, one day, spotted the artist sitting on her stoop and went over to talk. They’ve been in touch ever since.

“She encourages me to think deeper and longer about my work,” says Wallace, who likens Maynard to “a guide, always planting little seeds and being supportive and affirming. She’s a hidden gem, but her presence is energizing. And she’s just one phone call away.”

The artists check in regularly and, as a group, comprise a “beloved network,” says Naeem. “Valerie is one of the elders who has earned that type of respect.”

For her part, Maynard seems content to carry on and persist, valuing privacy over public acclaim. She appreciates the stillness inside her home. “I spend a lot of time just being quiet,” she says. “Sitting here, you’d never think all those buses and trucks are out there with all that noise going on.”

Maynard isn’t making any new art at the moment, and that’s okay with her. She’ll work when the spirit stirs. After all, that’s how she’s always approached her art, not as a commodity to be produced but as a humbling manifestation of her inner self.

“You don’t plan these things,” she says. “They just happen to you.”