A

Moment

of

Reckoning

Listening to Black voices in Baltimore.

Edited by Lydia Woolever

As told to the editors

Photography by Devin Allen, Kelvin Bulluck, Schaun Champion, Tevin Towns, Shan Wallace, and Isaiah Winters

News & Community

A Moment Of Reckoning

Listening to Black voices in Baltimore.

Edited by Lydia Woolever

As told to the editors

Photography by Devin Allen, Kelvin Bulluck, Schaun Champion, Tevin Towns, Shan Wallace, and Isaiah Winters

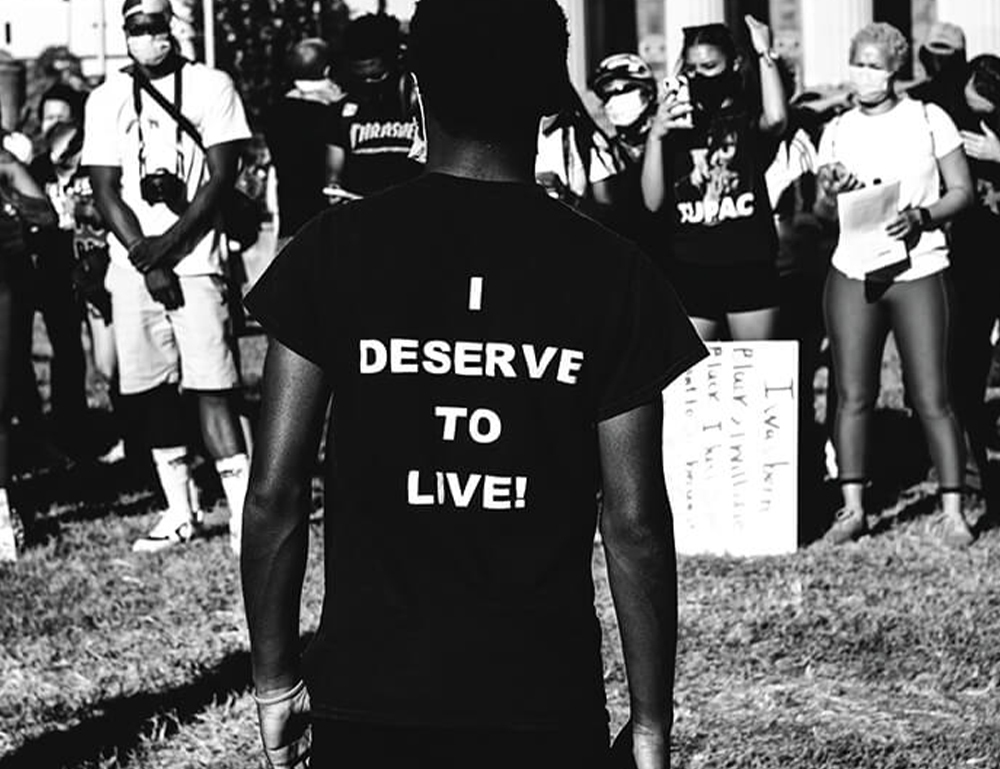

“UNTITLED,” 2020. BALTIMORE CITY HALL, JUNE 12. PHOTOGRAPHY BY DEVIN ALLEN

IN LATE MAY, a horrifying video began to circulate of George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man who died in Minneapolis after being pinned under the knee of a white police officer while pleading more than 20 times: “I can’t breathe.”

The loss of Black life at the hands of law enforcement has become a familiar story in America. Just five years earlier, Baltimore had been at the center of similar anguish after Freddie Gray died from injuries suffered while in police custody. But this time, the grief and outrage over Floyd’s tragic death incited protests that would ripple out across the entire country, forcing many to realize that, a century-and-a-half after emancipation and a half-century after Jim Crow, systemic racism remains entrenched in the United States.

“I saw generations, decades, of frustration,” local artist Ernest Shaw Jr. told PBS in the aftermath of the 2015 Balti-more Uprising. “I don’t think it was directed solely at police officers. . . . It was directed at the system.” In that same vein, this national outcry is about much more than police brutality and the failings of our criminal justice system. Systemic racism and racial inequality are being called out in all aspects of society: education, employment, health care, housing, voting rights, incarceration—and anti-racist allyship among non-Black people is at an all-time high. Since the death of George Floyd—after Ray-shard Brooks, Tony McDade, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and Elijah McClain—there has been an undeniable shift in public sentiment and a newly urgent refrain: enough is enough.

But it does raise the question: With generations before who fought tirelessly for civil rights—from Frederick Douglass to Lillie Carroll Jackson to Thurgood Marshall to Elijah Cummings, to name just a few here in Baltimore—what makes this moment different?

Perhaps, in part, it’s the coronavirus pandemic, which has given many time to reflect, as well as witness the disproportionate impacts of COVID-19 and its economic fallout on minorities. Certainly, the omnipresence of cellphone video and social media is documenting racial violence and making it difficult to look away. Likely, the protests have also been fueled by a polarizing president, who has stoked racial tensions and failed to unify the nation.

All the while, city streets are being renamed, Confederate monuments are coming down, police reforms are underway, and across America, hundreds of thousands of protestors of every color, age, and creed have been out there, day after day, fighting for justice and equity on a scale never before seen in this country. Once a rallying cry for activists, Black Lives Matter is gaining acceptance as basic truth.

Two months in, it’s clear that this reckoning is more than just a moment. But where do we go from here? Will there be meaningful, lasting change?

On the following pages, we listen to local Black leaders as they speak to these historic times, share their own stories, and pose hopes for the future.

“It’s better late than never...Isn’t that the point? Continuing to talk about something until it comes to light,” says musician Eze Jackson. “I’m grateful for it, and I’m not going to stop. There’s more to talk about. We’re just getting started.”

MAHSATI “SUNNY” MOORHEAD

CO-ORGANIZER, MARYLAND STUDENTS FOR BLM, 17

PHOTOGRAPHY BY SCHAUN CHAMPION.

I’ve been protesting since I was about nine. I went to the Trayvon Martin protest in New York City. I went to an Eric Garner protest. I went to a Freddie Gray protest. When we first moved to Baltimore, that’s when Freddie Gray was murdered by the police. It was sort of by my house where all the uprisings happened. We went to help clean up when the uprisings settled down. It’s been really awesome to see all these people come together [this time]. Going to protests, I’ve seen many people of different races, different ethnicities, different backgrounds come together to fight for Black rights and human rights. . . . For the student protest [in Baltimore this June], a group of us talked about the demands: Racial bias training for teachers and students. Adding more books by African-American authors and scholars within the English curriculum. Just talking more about Black excellence. And implementing the Black Lives Matter movement within the history curriculum, because we definitely have been making history. I read the demands. Speaking in front of all those people gave me confidence to keep pushing with activism. We need to have more conversations about race, anti-Blackness, white supremacy, and white guilt. I think Black kids are more open to talking about race. It’s still very hard for my white peers. That’s also what we were fighting for in our demands. . . . Young people have been fighting for years for what’s right. And with social media, anti-Blackness is more clear—we’re getting more information. But we learned from the people who came before us. We learned from Angela Davis, Malcolm X, Toussaint Louverture, Nat Turner, Ella Baker. We’re trying to finish the work that they started. Everyone’s waking up now. I know that change is coming. But I’m still on the edge. This has been 400 years of “change is going to come.” It’s been slow to change.

—AS TOLD TO MAX WEISS

“No justice, no peace. Prosecute the police.” —Baltimore youth protest, June 1.

EZE JACKSON

MUSICIAN, COMMUNITY ORGANIZER, VETERAN, 39

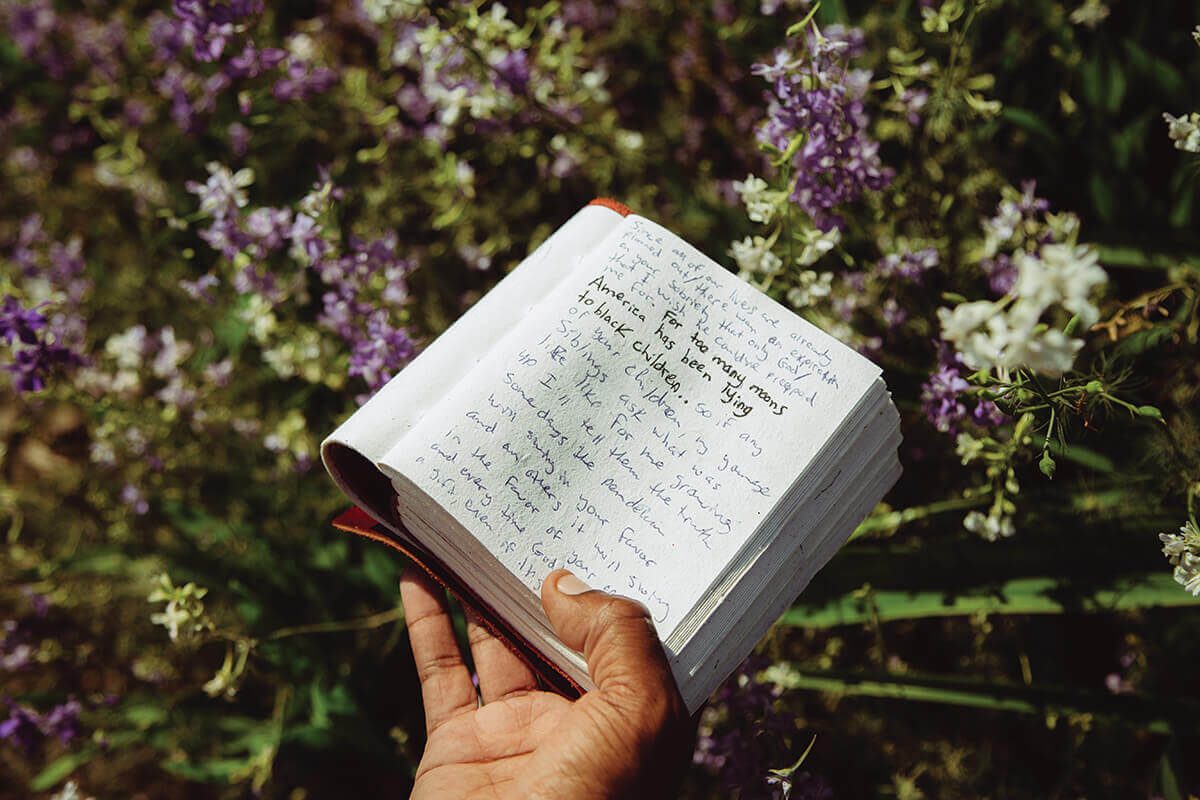

JACKSON WRITES AT THE COMPOUND. PHOTOGRAPHY BY TEVIN TOWNS.

I’ve always felt like artists should help push social agenda. My mother raised me on protest music. Marvin Gaye. Stevie Wonder. She was a big Public Enemy fan. Those sorts of artists were always my favorite musicians. When I left community organizing in 2014, I never felt like I was totally leaving the movement. With music, I could say what I want. I didn’t have to worry about my job being like, well, that’s not the position we’re taking so you have to be quiet. My mother would always tell me stories about what was going on in the world when certain songs came out, like Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come,” and the fact that she could remember was always fascinating to me. Recently, when we had protests here in Baltimore, they played my song, “Be Great,” [outside of City Hall]. To see my music providing a backdrop for this moment was humbling. I definitely cried. And now people have been pulling “Unapologetically Black” back up, which I wrote a few years ago when a lot of stuff was happening—Philando Castile, Alton Sterling, post-Freddie Gray. That’s the goal, I think. An artist’s job is to articulate the human experience. When people identify with that, it’s a blessing. . . . I think it’s better late than never. Isn’t that the point? Continuing to talk about something until it comes to light. I’m happy that everybody is talking. In this particular moment, it’s scary to think about how much longer we would’ve gone before people woke up. In the Black community, we watched America take a nap during the Obama era. I can remember having arguments with my white, liberal friends during that time. It was just this dismissal. Like, oh, it’s not really that bad. And now I’m seeing some of those same people go, oh, I had no idea that I was not paying attention all this time. I’m grateful for it, and I’m not going to stop. There’s more to talk about. We’re just getting started.

—AS TOLD TO LYDIA WOOLEVER

JUSTIN TIMOTHY TEMPLE

YOGA TEACHER, 37

To me, as an individual who wakes up every morning and purposefully breathes, it’s a radical act, particularly when you’re aware that that there are external forces that would rather I not. I’m going to do everything I can to make sure that I continue to teach people to be with their breath, because it’s a radical act. That's just another way for us to be free, to sit with ourselves, and to acknowledge and be present with this thing that so many others would take away from us. It's a declaration of no—you can’t have it, it is ours. . . . Who is this a moment or reckoning for? For me, all of these truths that we have exposed, all of these ideas and instances of exactly how bad things are were talked about in 2015, in 2014, in 2013. . . in 1954, when my dad was one of the first Black people allowed in a school. So, for Black people, it’s not really a moment of reckoning. It’s a moment of you guys caught up. The reckoning is what did I miss, and how do I make sure that it doesn't happen again? . . . . Because of COVID-19, you couldn’t have a more crystallized moment where more people were paying attention to the internet. It came after three months of people being stuck inside. Those two converging truths led to not only a desire for people to want to join in community, but a desire for things to be better than how they are right now. People are operating within the sense of collective care. People really want what’s best for the group. That, to me, is hopeful.

—AS TOLD TO JANE MARION

ERNEST SHAW JR.

PAINTER, EDUCATOR, ADJUNCT PROFESSOR, MICA & BCCC, 51

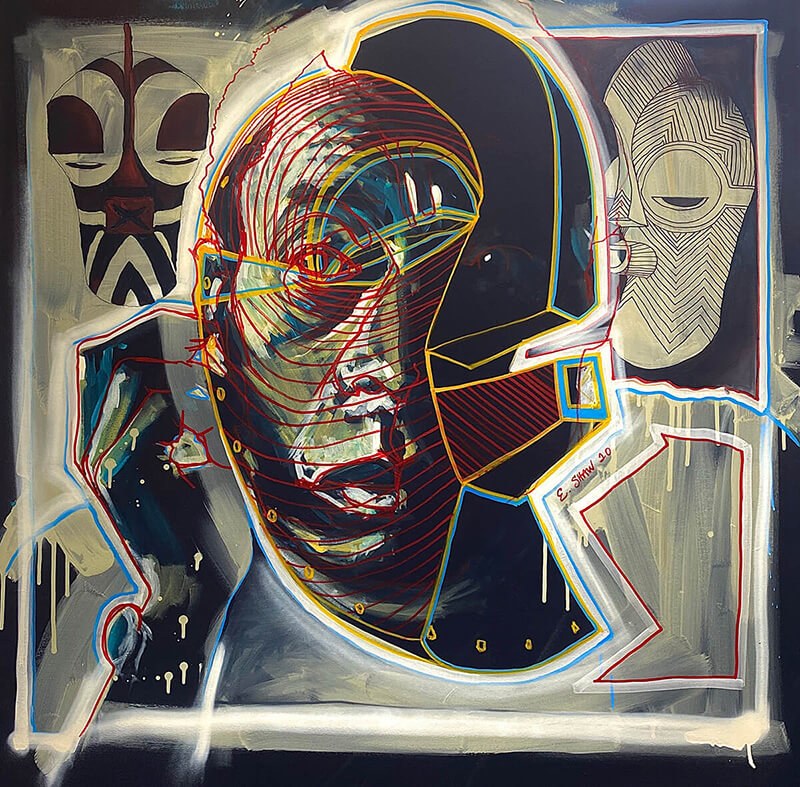

ABOVE: “SONGYE.” BELOW: “EVIDENCE.” COURTESY OF ERNEST SHAW JR.

When the officer who had his knee on George Floyd’s neck put his hands in his pocket, I think that specific action was the tipping point. That, on top of Breonna Taylor, on top of Ahmaud Arbery. It was rapid fire. It wasn’t simply the brutality, it wasn’t simply the taking of a human being’s life. But the putting of your hands in your pocket was a signal, and a symbol, of, I would say, Custer’s Last Stand. Just a very subtle, nonchalant action like putting your hands in your pocket. The arrogance associated with it . . . It’s like, I can kill you without even using my hands. I have the authority to invalidate your humanity, you know? I think the toughest part psychologically for a lot of people is that people of color, women, members of the LGBTQ community—so many have been fighting to have their humanity validated. That’s a basic human pursuit. Everybody wants some sort of validation that who they are and what they do is worthwhile. The problem is, when you brutalize other human beings, it’s an inhumane act. All oppressed people are asking is for you to be human, for you to validate your humanity, not to validate ours. I think that’s the difference in 2020. . . . This notion that there are just a few bad apples, that the overwhelming majority of police are good people, I’m going to push back on that. For certain groups of people, for certain members of our society, there is no such thing as good police. . . . Have I done everything right? No, but I don’t have a criminal record, I’ve always been employed, I have more than one degree, I co-parented two children, I’m a schoolteacher and an artist. But I’ve still been brutalized by the police. It doesn’t matter if you get straight As in school. It doesn’t matter if you’re an adjunct professor at a private institution. You are still subject at any time to get what is called your “[N-word] wakeup call.” Excuse me for using that language, but that is a part of the reality for Black people in this country. At some point no matter who you are, and it may happen multiple times. No matter how much money you make, or how many taxes you pay, or what neighborhood you live in.

—AS TOLD TO LYDIA WOOLEVER

TAWANDA JONES

MOTHER, TEACHER, ANTI-POLICE BRUTALITY ACTIVIST, 42

Jones at her Home under a Photograph of Her brother. PHOTOGRAPHY BY ISAIAH WINTERS.

With George Floyd, it took me back in so many ways to my brother’s death. [An unarmed Tyrone West died during an arrest in Baltimore in 2013.] Hearing his final words, calling out for his mother who had passed years ago, that really broke my heart. I saw law enforcement officers just completely disrespectful of human life, of a human being, and I think those screams for his mother are the catalyst for this struggle for civil rights. I’m not the only one who heard his cry, and I think his cry changed us forever. It made people know we are more than trending hashtags, buttons, and T-shirts. . . . Then Rayshard Brooks is killed [by police outside a fast-food restaurant in Atlanta in June] and it did it to me again. You relive your own trauma, your whole family relives their trauma. It happens over and over. Rayshard Brooks reminded me of Walter Scott. There was Tamir Rice, who was a baby, gunned down by police in a sacred place for children—a playground. What was his last thought? Eric Garner, who was choked out. Breonna Taylor. But what’s happening makes me know this work is not in vain. . . . We’ve had successes. Gag orders in Baltimore City police settlements have been banned. Johns Hopkins University de-laying the start of their own police force is a big deal. The movement to defund police is amazing. The entire world is protesting. You’ve got little children holding up signs. But it’s never going to stop, that’s what people are learning, until we make it stop.

—AS TOLD TO RON CASSIE

IYA DAMMONS

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, BALTIMORE SAFE HAVEN, 28

Dammons in front of Baltimore Safe Haven in Charles Village. Photography by Shan Wallace.

Time magazine was an achievement to those on the out-side of the trans community. [An image of Baltimore’s Black Trans Lives Matter march by local photographer Devin Allen made the magazine’s cover in June.] That’s not what makes me happy. What makes me happy is to see my community really get the resources and the education they need, because help is not on the way. All Black Lives Matter, including trans lives. That’s what our march was about for me. It was not about changing the narrative for our Black community, but including us. I’m making sure that we’re included. I’m on the frontlines, I’m fighting for my people, with unbelievable strength at times. The glitz and the glam that comes with the news? All of that is just hype for an old girl like me who was a survival sex worker. A lot of people do not talk about the difference between women who are willing to do sex work who have a college degree versus my girls who have been out here during COVID. My highest achievement was when I turned the key to the drop-in center and opened our mobile outreach unit and was able to put out those services [such as providing temporary housing, HIV and AIDs resources, and legal support, among others] right in the streets where trans women are. Baltimore is historically behind when it comes to programming for the trans community. There’s a stigma that says LGBTQ people will get HIV and AIDS, that trans people die at 35. At least one of us has been killed, no matter the color of our skin, every year for the last 10 years in Baltimore. Like, come on—is anyone listening? But this is the fight of all fights that I’m in...My hope for the future is that you include me at the table. Take my life and my trauma seriously. Don’t come through right now because it’s an “it” thing to do. I want you to show up every day. I’ve been here as a Black trans woman in survival mode way before this, and I’ll still be here when all of the lights are over with. Last year, there were at least 27 of us who died in the United States. We are now at 21 this year. Don’t forget us, because we’re still here, going through the same issues, and until you tap into the resources we need, we’ll still be fighting.

—AS TOLD TO LYDIA WOOLEVER

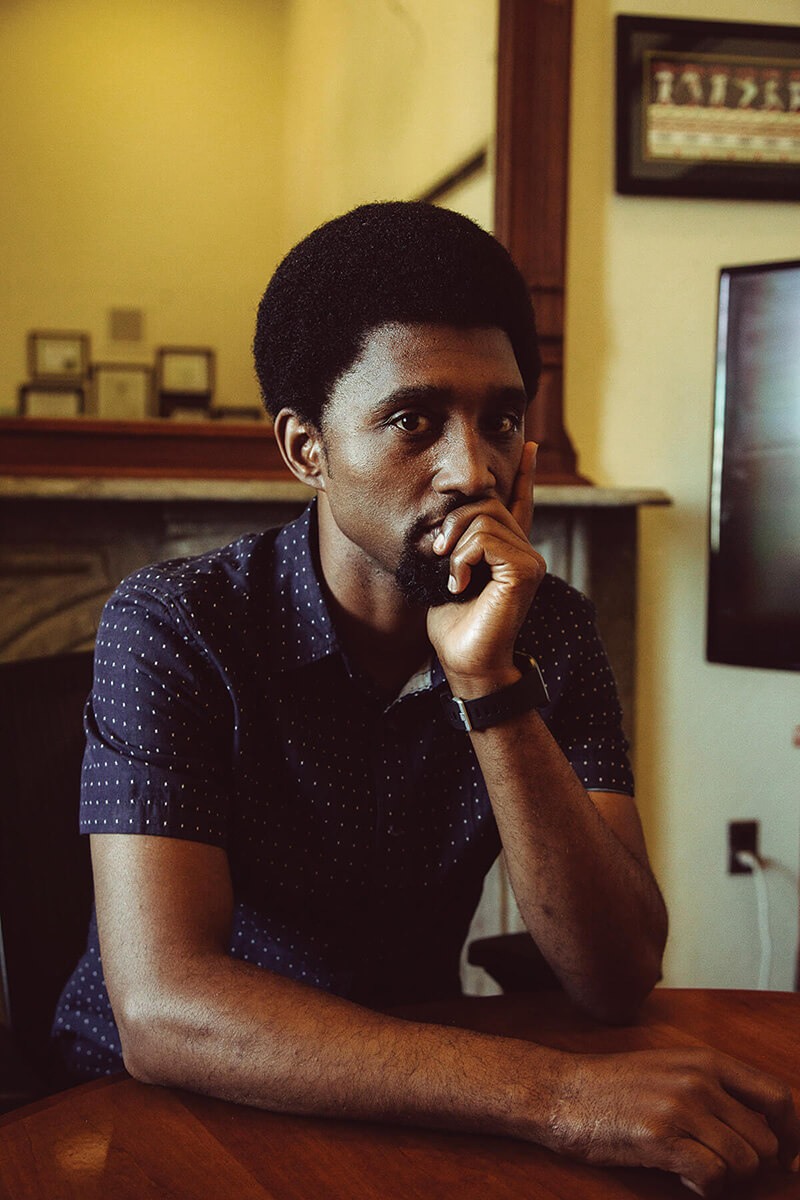

KONDWANI FIDEL

POET, AUTHOR, 27

FIDEL AT THE CYLBURN ARBORETUM. HIS NEW BOOK, "THE ANTIRACIST", IS DUE OUT AUGUST 11. PHOTOGRAPHY BY SCHAUN CHAMPION.

In moments like this, when I don’t know how to make sense of the world, I talk to Zoe Spencer, one of my college professors at Virginia State University, who is a sociologist, about the group psychology of what’s happening. Experience is a big part of how you process things. I talk to [Baltimore writer] D. Watkins and Valencia D. Clay [a National Geographic Education Fellow and humanities teacher at the Balti-more Design School]. They’ve been on this Earth longer than me. They have more insight, even though I’ve been Black and from Baltimore for 27 years. But what I’m really pulling from them is inspiration. When you’re doing this work, it gets discouraging. I have more bad days than good days. My writing, when you hear it or read it, it’s very emotional. I never wanted to be involved in politics, but art pushed me into politics. . . . The thing about being from Baltimore is that we’re always on the Jumbotron for the corrupt mayor, the dysfunctional police, the violence, the poor schools. That’s plastered in your face every day. At the same time, we don’t ever get around to addressing the poverty that’s behind all this. It’s like nobody wants to have that conversation. . . . I think symbols are important, the Confederate statues and flags coming down, but I want the real change, too. I want both. I want Black people to be treated the way white people or people with money are treated. That’s it.

—AS TOLD TO RON CASSIE

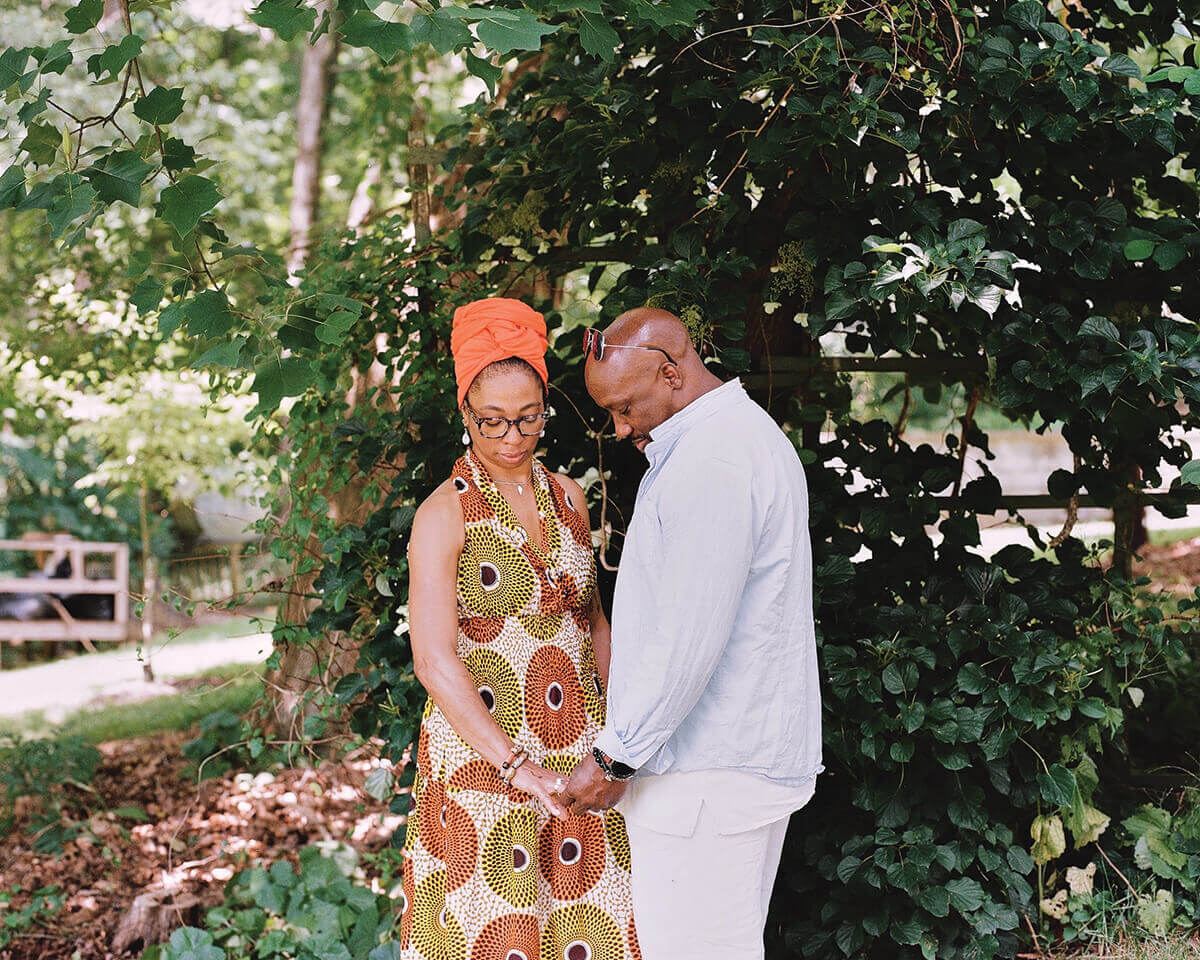

DAVE & TONYA THOMAS

RESTAURATEURS, 52 & 54

The Thomases on their family land in Cockeysville. PHOTOGRAPHY BY ISAIAH WINTERS.

DAVE: My family was the second African-American family to move into an all-white neighborhood in Riviera Beach, Maryland. It was a really, really tough existence. My family moved there to get away from the city, to give us a better way of life, but little did they know that we’d be walking into a hotbed of racist anarchy. We had crosses burned on my lawn in 1973. In junior high school, I was around a bunch of people who didn’t see a lot of African Americans unless they went to school. The community was very prejudiced. Some of them were just out-and-out rac-ists. They wanted to get rid of us and they would intimidate us. I had an Afro-pick in my back pocket and one of the kids on the bus grabbed it and stabbed me in the side. That’s the kind of stuff you dealt with—it just became the norm. You just prepared yourself for it. This is stuff that I have dealt with all of my life, so my voice was set in stone for me long before I even knew that I had one. My wife and I have always wanted to talk about things that would help uplift our people, so my voice isn’t going to change now. We are going to continue to push this narrative so that people understand that out of struggle comes beauty. Hopefully, after the struggle, there will be some ease. That’s what our goal is—to continue to educate people so we can hopefully turn the corner on this one day.

TONYA: That’s why we are always telling the story. We don’t want the history to be erased, we don’t want people to be able to say that’s not what happened, what are you talking about? We have to continue the narrative. There’s a group in this country that if they could, they would erase it and say it didn’t exist, that it was a hoax.

DAVE: Racism is about one group oppressing another group and the power and systems that are in place to allow that to happen—that’s what racism is. Black people have never been in the position to oppress anybody, not in this country. Racism was brought out of white people not wanting Black people to be equal, not wanting Black people to be free, so it is not a problem that we can fix ourselves. We can yell and scream and protest, but unless the white people of the country stand up and say that racism has to end, it’s never going to end. Until they embrace it and say, ‘We are not going to stand for this anymore,’ it will continue.

—AS TOLD TO JANE MARION

JINJI FRASER

OWNER, PURE CHOCOLATE BY JINJI, 37

I know that I’ve gotten to where I am because of the way I’ve interfaced with the majority community. What that means is that I grew up a swimmer, went to McDonogh, went to Indiana University. It’s just this training that we all get in these different ways for what’s necessary to blend in and make it through. I’m in such gratitude that this moment has finally come...My earliest memory of being different or being the other person was in school. I remember white girls and their parents wanting to play with and touch my hair—that goes back to the whole idea of ownership, like someone thinks they own a piece of you, that they can, without permission or any kind of conversation, handle you and your body. . . . I feel like, through the truth of fully being myself without the fear of not being accepted, I’m able to freely and openly bring more integrity to what I’m doing now. That’s a gain in principal and purpose. I look forward to the research this will allow me to do into my specific craft, and I look forward to the openness of the conversations that will come.

—AS TOLD TO JANE MARION

SHARAYNA CHRISTMAS

FOUNDER, MUSE 360 ARTS, 36

Christmas at her Muse 360 office. Photography by Kelvin Bullock.

I’ve had to really rethink what radicalism is in this moment, and think about it in a sense of peace and balance. I’m always doing this work—all of my work is really African- and Black-centered. And now everyone is marching and every website says “Black Lives Matter.” But it needs to be more than that. It needs to be action. This country has been built on the backs of my ancestors. That’s a cliché thing to say, but it’s real. Yes, there are injustices being done by the police in terms of what the Black community has experienced for centuries. But there are also things that have been systematically happening that people need to zero in on. It can be as simple as getting someone’s name right, or asking me how I’m doing—I know it can’t compare to someone dying at the hands of the police per se, but it’s death by a thousand cuts. And that’s what I think a lot of institutions, predominately white institutions, don’t understand. We’re constantly triggered by these moments. So it’s really important for me to maintain the balance of a radical love for myself and for my work with my youth. And to let them know that they’re loved. My youth are really hurting. They are suffering. They are hopeless. Yes, people are marching and listening, but they also know people are dying. . . . Racism is not going to be solved overnight. There are tons of books and resources, but it really comes down to how you treat people. It has to start with yourself. When people quote, “The revolution will not be televised,” it has nothing to do with television. It’s not televised because it’s happening inside of you.

—AS TOLD TO LAUREN COHEN

FREEMAN A. HRABOWSKI III

PRESIDENT, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND, BALTIMORE COUNTY, 69

Hrabowski stands on the roof of the administration building at UMBC. PHOTOGRAPHY BY ISAIAH WINTERS.

As a society, we are being forced to see our-selves, to look at ourselves in the mirror and speak the names of those who have been the victims of structural racism. Protestors are doing important work, making visible the signs of discrimination and the deaths from police brutality. Now, there is a challenge with respect to that. What comes after the protests? Am I asking myself the question, what role am I playing in all of this?...For me, education is obviously very important, and we have to do everything we can to ensure that income inequality and zip codes never impact the quality of education a child receives. In terms of higher education, we have to look at our-selves in the mirror, too. Are we assisting first-generation college students of all races and genders? At UMBC, we have increased the number of Black faculty, but we still have a deficient faculty of color...One thing we have to realize is anti-Black racism directed at African Americans is a 400-year-old-plus phenomenon. I grew up in Birmingham, Alabama, in the ’50s and ’60s, when marchers being knocked down by fire hoses and children being put in jail first began to make many Americans feel the depth of hatred in this country. In 1963, I was 12 years old when those four girls were killed in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing. One of the girls went to my school. My mother was a teacher and another girl had been in her class. Seeing how those little girls died was horrific. Period. You don’t want to do anything after something like that. But you can’t stay in that place. What Dr. King said inspired me, that tomorrow can be better than today. And tomorrow is today and we have to act.

—AS TOLD TO RON CASSIE

JAMYLA BENNU

OWNER, OYIN HANDMADE, 44

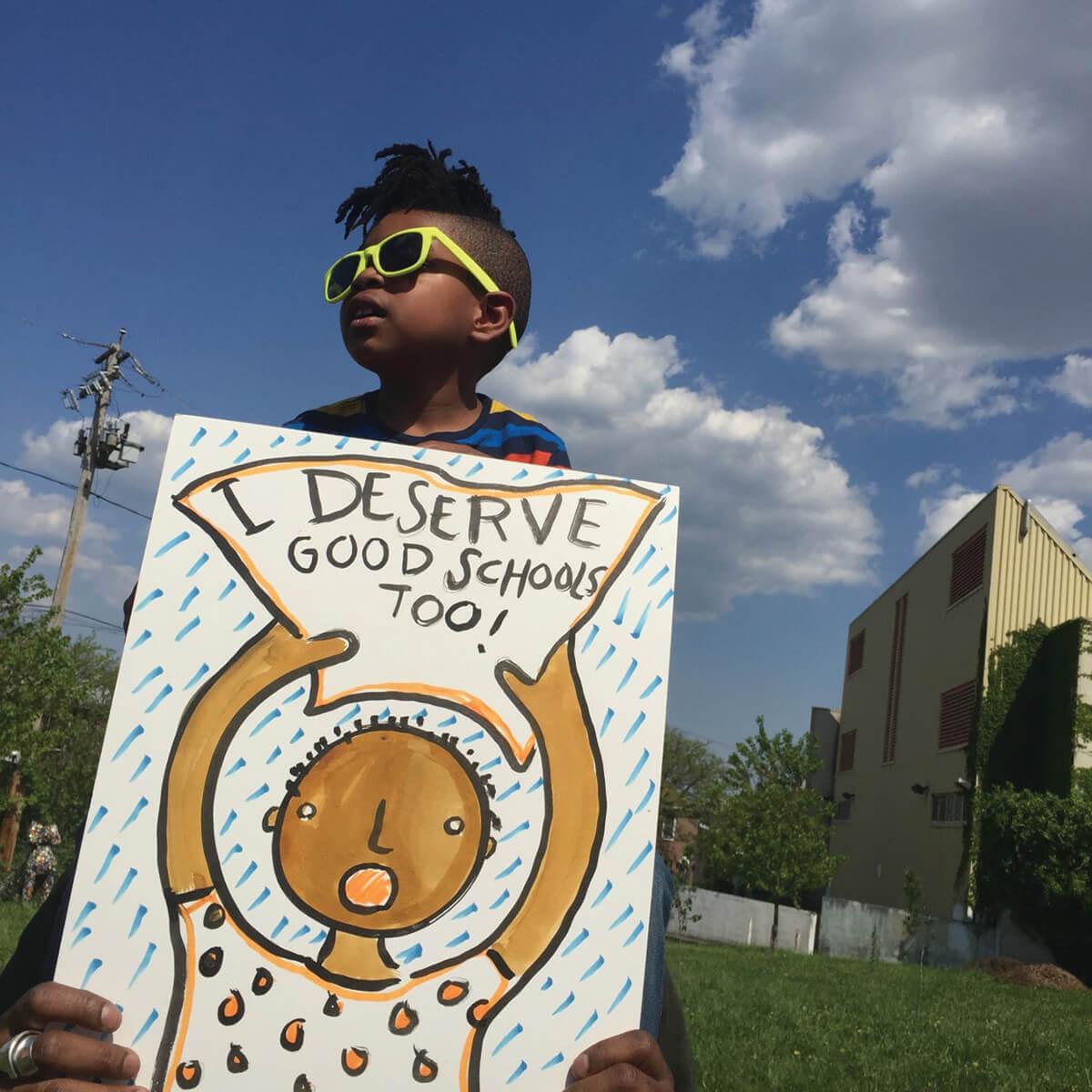

BENNU’S SON AT A 2015 MARCH IN BALTIMORE. COURTESY OF JAMYLA BENNU.

Like most Black American parents, we’ve been talking to our children about race, equity, and the brutal history of our country since they were very small. In age-appropriate ways, we have always tackled the tough questions and tried to be honest with them about the world they live in. This is an important part of rearing Black children in an anti-Black society. We have to inoculate them, little by little and early, so that—hopefully—their first exposure to these concepts doesn’t break them. These are also Baltimore children, and we attended protests as a family around the police killing of Freddie Gray five years ago. They were tiny. I have feelings of fatigue and disgust that here we are again. Here we are some more. Here we are, continuously, and still. They’re less tiny, now. My oldest just turned 12—the age Tamir Rice was when police slaughtered him in the park while he was playing with a toy. I had to grapple with my urge to protest and my simultaneous urge to protect my children. But is one even possible without the other? When are they the same thing? When are they in direct conflict? In Dani McClain’s book, We Live for the We: The Political Power of Black Motherhood, she talks about how Black mothers have traditionally “metabolized fear” on behalf of their children. That expression was so powerful. Because yes, we eat our fear for them and turn it into protection, into action. But also, we risk being consumed by it, if we're not careful. We risk it becoming the kind of “preexisting conditions” that lower our life expectancy and make us more vulnerable in a pandemic. [In early June,] my metabolizer broke. My “supermama” mask slipped. My children saw my fear. That hadn’t been a part of what I'd talked to them about. History? Yes. My own personal horror? No. . . but I guess it was time. We were all able to grow closer as a family after having the conversation that was prompted by those tears.

—AS TOLD TO JANE MARION

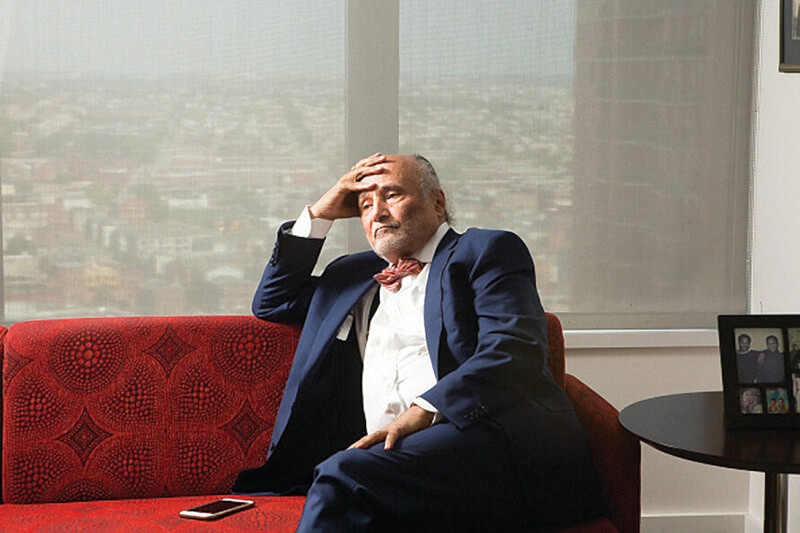

WILLIAM H. “BILLY” MURPHY, JR.

LAWYER, FORMER CIRCUIT COURT JUDGE, CIVIL RIGHTS ADVOCATE, 77

Murphy in 2015 while he was representing the Gray family.

People are absolutely outraged by what they’ve seen. And each outrage trumps the last one—it’s unlike any we’ve seen be-fore. But there are various factors that con-tribute to what the outcome will be. One of those is press coverage: During the Nixon administration, the press stopped covering the civil rights movement—figuring the out-rage would go away—because of an unspoken agreement with the powers that be. But social media spreads this like wildfire, and now families and communities are talking about it for the first time. This last incident in Minnesota just horrified people. They said, “Is this racism? I can’t be in favor of this.” Every structure has to change. Color remains the symbol of inferiority—we still see that in the criminal justice system, housing, and banking. And it’s the younger generation that can affect that change through re-education. Look at the historically fast shift in attitudes toward the LGBTQ community. The younger people are just not taking it anymore. And when white folks fight against bias, then you get real change. As far as Baltimore goes, it’s time for the Black leaders to get some backbone—most have just been kowtowing to the white establish-ment. Unless our new mayor, Brandon Scott, comes out with a radical new approach, there will be a failure of leadership. Incrementalism does not move the needle.

—AS TOLD TO KEN IGLEHART

REVEREND ALVIN C. HATHAWAY SR.

PASTOR, UNION BAPTIST CHURCH, 69

I was born in the 1950s, so much of my life has been a constant fight for civil and human rights. I grew up on Druid Hill Avenue in Upton, but 60 years later, it’s clear it has been a community of disinvestment. This highlights that in Baltimore, we have created two different experiences: communities of advancement and those of decline. This moment of reckoning means that, first, we must acknowledge the disparity that exists, and institutions must become intentional about dismantling racism. Finally now I see recognition across the board that our society, and city, are going in the wrong direction. Unfortunately, though, I've seen similar conversations occur after the riots of 1968, and we can point to very few accomplishments that have resulted from those. I also participated in the One Baltimore effort after the 2015 Freddie Gray incident, and, despite the full force of the federal government, we accomplished very little in the way of tangible results. And now we are at this watershed moment again, and, if we are not careful, we will repeat the patterns of the past and revert back to business as usual. I will resist that from occurring with everything I can. I’ve lived long enough and interacted with enough people that I can say empathically the hearts and spirits of the people of Baltimore are desirous of change in a more equitable way. My hope is that, as we walk that journey, we will keep our hands to the plow and not turn back.

—AS TOLD TO KEN IGLEHART

SHELONDA STOKES

PRESIDENT, DOWNTOWN PARTNERSHIP OF BALTIMORE, 48

STOKES OUTSIDE OF THE DOWNTOWN PARTNERSHIP BUILDING. PHOTOGRAPHY BY SCHAUN CHAMPION.

I do believe we’re seeing meaningful change. I think about every step we’ve taken in our expansion of freedom over the years. In the past, there were always certain people willing to challenge the status quo. But now it’s not just that one group of people, it’s everybody, all colors, standing up—even some police taking a knee. And businesses, too, are standing up. This is a moment in history. And all this means more for us than for many other cities. For a while, we were like the lone actress on the stage, with people thinking that these issues were only about Baltimore. But now you see everyone grappling with them, though we’re probably further ahead in the process of change because of Freddie Gray. I believe we have to see positive change now. Because those who were in power for so long are, in many cases, no longer able to wield it. It’s the masses now that have the power. Now, because of George Floyd and others like him, people can start to visualize their own sons or daughters being in the same position. We saw him beg for his life. And you could see that life come to an end. People are now forced to take a position. They can’t stand on the sidelines anymore. And the one factor that makes this time different? Audio-visual technology. For hundreds of years, injustices against people of color were underreported—or not reported at all, much less prosecuted. Before, people could question a report of injustice, because there was no proof. But suddenly we have cell phone cameras, security cameras, YouTube, and the media spreading the word—that’s played a tremendous role in providing a lens for the world to see what’s going on. Those eight minutes and 46 seconds of video were pivotal.

—AS TOLD TO KEN IGLEHART

Brandon Scott

PRESUMPTIVE BALTIMORE CITY MAYOR, 36

SCOTT AT CITY HALL. PHOTOGRAPHY BY SCHAUN CHAMPION.

I can’t tell you how many protests I went to. Pretty much for the first two weeks [after George Floyd’s death], if there was a protest, I was there. My first instinct is always to be present and be seen in the moment, but especially one that has a higher meaning to me as a young Black man. In this case, it was also critical for me to be there to make sure that our young people were being looked after, that outsiders were not coming in and trying to hijack their moment, their movement. That people were not putting them at risk. I always say that when I was growing up, aside from [late Congress-man] Elijah E. Cummings, I couldn’t reach out and touch most elected officials. I made a point in my career in service to be present so that the next generation could reach out and physically touch me. They could talk to me, they knew me, I was in their schools, I’d be coaching their teams, in their neighborhoods. . . . Being Black in America is exhausting. It’s exhausting. We have to think about things that no one else does. I always tell younger politi-cians, especially Black ones—you don’t get the breaks that anyone else gets. When you step into your job, you have to be 10 times better than anyone else because the system is set up for you not to be there. I heard from reporters that the other can-didates said it wasn’t mayoral for me to be down at the protests and my response to that was, actually, it is very mayoral. If you’re the mayor of the people, you have to be with the people. . . . Above all else, when my title is gone, I’m going to be Brandon from Baltimore, from Park Heights, who was involved in community work before coming to City Hall.

—AS TOLD TO MAX WEISS