News & Community

Century Paradiso

For the past 100 years, John Pente has been watching the world change from the same one-block radius in Little Italy.

eventy-five years ago, John Pente’s Model T Ford was the talk of Little Italy. He bought it used for $12, and had it, as the kidsmight say these days, completely tricked out.

The 25-year-old painted the car’s wheel spokes red and the fenders around the tires bright blue. He installed a homemade radio under the rumble seat that tuned in the city’s one station.

“It was my pride and joy,” he says with a smile at his kitchen table at 222 South High Street, the same house he’s lived in his entire adult life. “I polished that up every day.”

As he speaks, April sunlight filters through his windows and lands on his home’s sturdy plaster walls—walls he built himself back when he had that car.

“I know where every nail is in this house,” he tells me with a laugh. Although Pente is 100 years old, I don’t doubt him. Friends and family say he’s sharp as a tack. Less than two minutes with him proves this.

He points to an old photo that his son, Joe, has just retrieved from the basement. A young John leans up against the car, weight shifted on one leg, one arm slung proudly along the driver’s side door. His tie blows in the wind, his hair is dark brown, his pants are immaculately creased. He looks like a million bucks.

“I made a rumble seat back there,” he continues, almost not able to talk fast enough. “And I used to take my girlfriends for rides. Nobody else had a radio. I would put the top down and look at the stars and it was beautiful.”

Those were his “drugstore cowboy” days, as he calls them, when he wore custom-made suits and hats from local tailor shops with two-toned Cuban heels, and hung with his crew at a Jewish-owned Little Italy drugstore on the corner of Pratt and High Streets.

There aren’t many old-timers left in the neighborhood who remember that car, but people still certainly know John Pente.

“He’s too much!” says Pente’s longtime friend Dominic Leonardi, affectionately known around Little Italy as “Fuzzy.”

Leonardi, 84, recounts Pente’s custom of buying too much fruit for his kitchen table fruit bowl and then generously putting a few in a paper bag and handing them to off to his friend.

“He’s always givin’ me something,” he says, a smile in his voice. “If he gets a cake, he puts a slice in aluminum foil and has me take it. I’ll tell you what, that man is too much.”

It’s obvious, however, Leonardi’s not just talking about oranges, bananas, and cake. He’s talking about his oldest friend in the entire world: A man at the very center of a small universe and a large family. A man that is always glad to see you, and will always, without a doubt, make room for you on his bench.

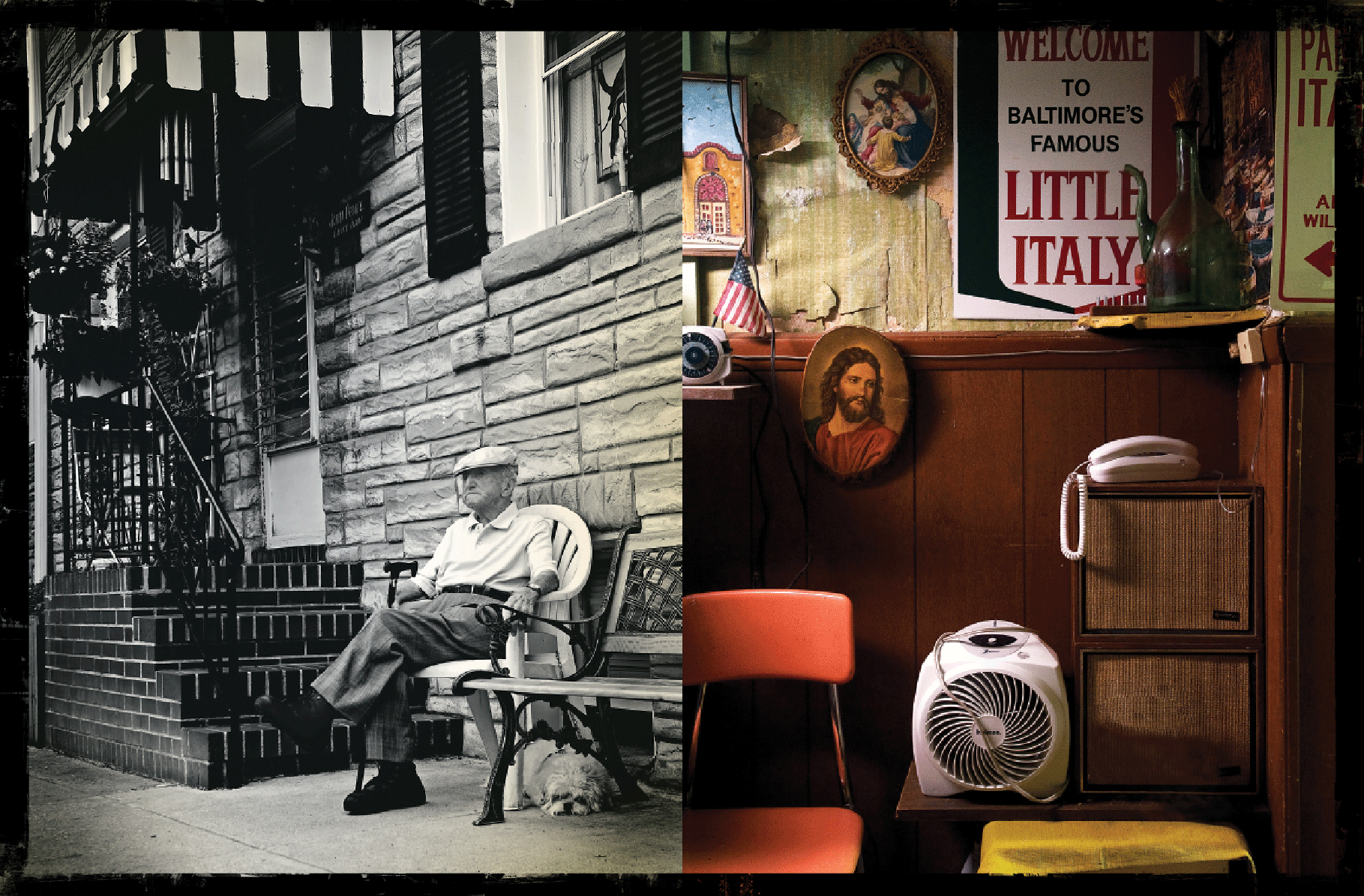

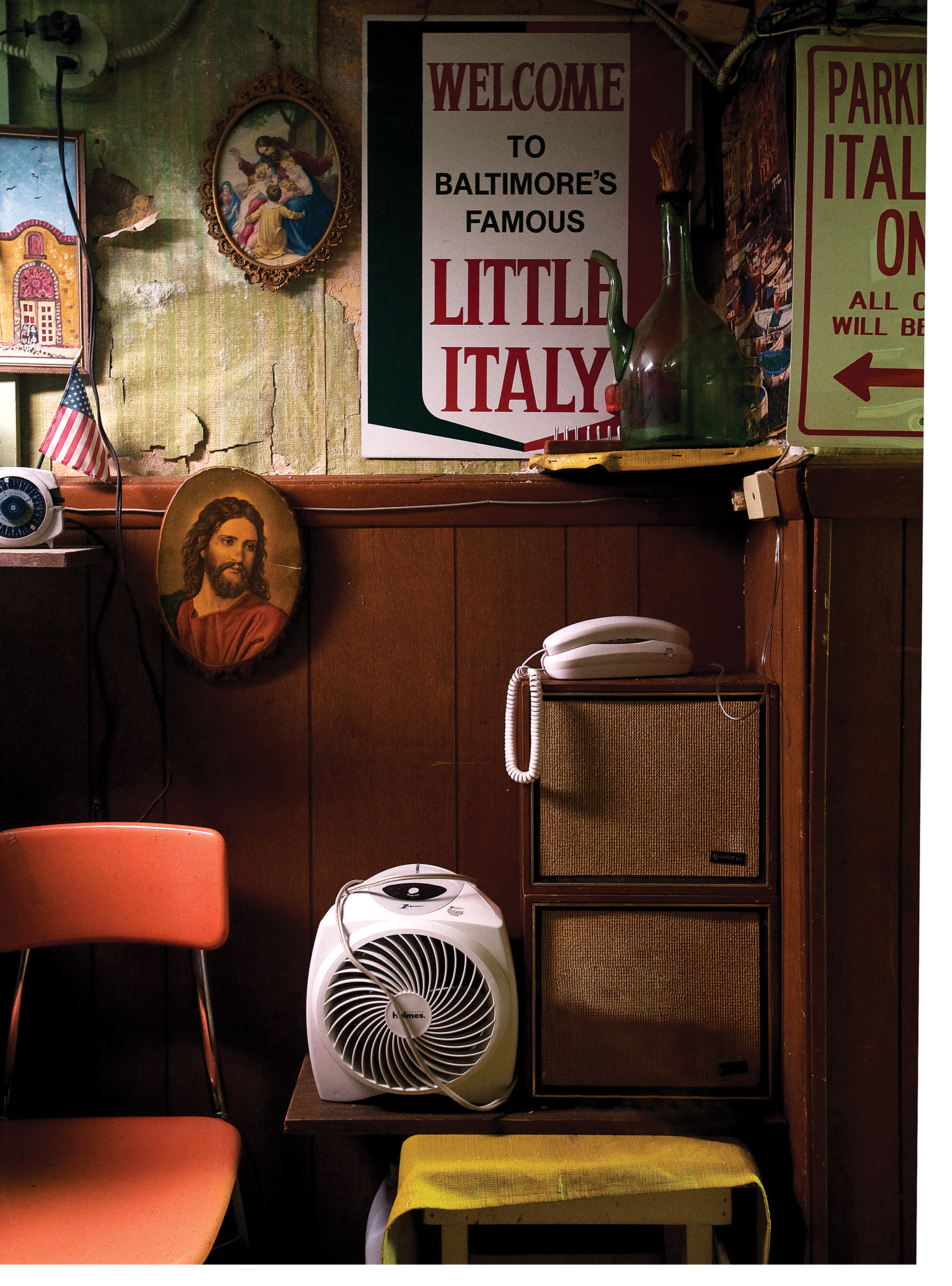

He’s known as “Mr. John” around the neighborhood and, chances are, if you’ve visited Little Italy even just a handful of times, you’ve seen his house. If you’ve brought a chair to the neighborhood’s annual outdoor summer movie festival, you might have sat a few rows in front of him—and unknowingly reaped the rewards of both his graciousness and centrally located home, since the festival beams its projector out of his third-floor window.

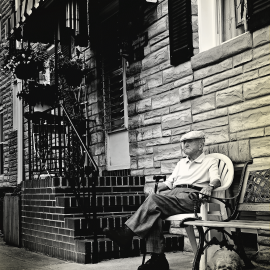

His sturdy three-story home—honored as a “centennial home” last summer by Baltimore Heritage for being in his family for over 100 years—sits at the corner of South High and Stiles Streets, directly across from Isabella’s Pizza and catty-corner from Caesar’s Den restaurant. A line of well-worn wooden benches and white plastic patio chairs sits by its side entrance on Stiles Street.

His sturdy three-story home—honored as a “centennial home” last summer by Baltimore Heritage for being in his family for over 100 years—sits at the corner of South High and Stiles Streets, directly across from Isabella’s Pizza and catty-corner from Caesar’s Den restaurant. A line of well-worn wooden benches and white plastic patio chairs sits by its side entrance on Stiles Street.

“There is nothing bad about Mr. John. Absolutely nothing,” says Tina DeFranco, co-owner of Caesar’s Den. “He is the most kind-hearted man. He has opened up his home to us for so many years. His door is always open to anyone.”

If the weather’s nice, Pente’s “gang” (a familial group of Italian-American old-timers with a name roster straight out of The Sopranos) will inevitably be hanging out on those benches and chairs. Sometimes Pente will be there with them, his devoted little white dog Gina—named after old-time Italian movie star Gina Lollobrigida (“She was beautiful,” Pente sighs)—by his side. Other times he’ll be inside fixing dinner or visiting with local family members—usually his daughter Marge Schwartz-Pente or oldest son Joe—that are in and out of his house, their childhood home, every day of the week.

Pente has spent his entire life in a one-block radius. In a world where many of us are transient, often crisscrossing the country to follow work or loved ones with our childhood homes a distant memory, this is awe-inspiring.

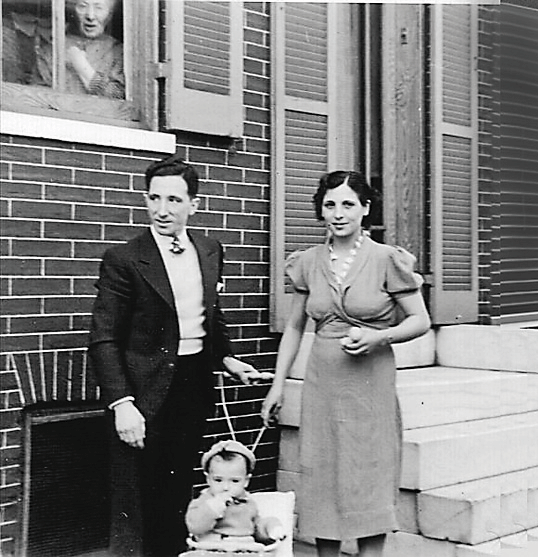

He was born half a block away on Stiles Street, and grew up next door at 220 South High Street. After he married in 1936, he and his late wife Margaret moved to an apartment on Fawn Street (now an annex to Sabatino’s Restaurant). Purchased by his grandparents around 1904, the house at 222 South High Street was owned by his father, who passed it on to his son after Pente’s uncle died in 1941.

At the time, it wasn’t much of a home. It was an instrument repair shop and a bachelor pad. But with the help of a few friends, Pente renovated the property and rebuilt it from the inside out.

At the time, it wasn’t much of a home. It was an instrument repair shop and a bachelor pad. But with the help of a few friends, Pente renovated the property and rebuilt it from the inside out.

Pente has gone to the same Catholic church, St. Leo’s on South Exeter Street, his entire life. (“I’m still the oldest alter boy in St. Leo’s,” he jokes. “I got a medal to prove it.”) He played on piles of wood at the Inner Harbor when it was just a smelly lumberyard. He lived in Little Italy before it was Little Italy, when immigrant Jews and Italians lived side-by-side, cooking for one another, congregating on sidewalks on summer nights amidst the melodies of neighborhood musicians, their children sleeping on stoops when it got too hot inside.

People were happier back then, he says. Foods were simple, and clothes were plain. They had less, but their lives were full.

Happiness is “not how much money you make. It’s not true,” Pente states with great certainty. “We were happier in the old days because we never had money. If you had a few dollars in your pocket, you were rich. We had communication.”

Pente is the picture of good health. He’s a tad smaller than he once was, and his hearing is a little strained, but overall he’s had remarkably few health problems in his 100 years. In fact, he’s never had a single surgical procedure. He’s barely had more than a cold. So, what does he eat?

He stops to think, taking great care in answering. He doesn’t hurry answering most questions. After all, what’s the rush?

“I’m a lasagna eater,” he says.

He’s about to continue when he stops mid-sentence, turns to face his daughter across the kitchen table and asks how he looks. While Pente’s been in the news before because of Little Italy’s summer film festival, it’s not everyday a reporter is in his house.

“Is my hair messed up?”

“You look fine,” Marge answers warmly.

“Okay,” he says, laughing.

He used to cook nearly every day until his one significant health problem—a bout of sciatica earlier this year—slowed him down.

“When I cook, I love the old Italian style. I like lasagna, ravioli, Italian meats. Things like that,” he says.

Pente started cooking at age 14 when he worked at a small grocery store, about a block away from his childhood home next door. When he wasn’t translating, reading, writing, and keeping the books for the Italian-speaking owners, he was helping them prepare hot meals for immigrant workers, all manual laborers, during the workweek. It was this early experience cooking for crowds that made cooking for his large family such a cinch. He’s cooked for—and packed into his row home’s modest dining room—up to 18.

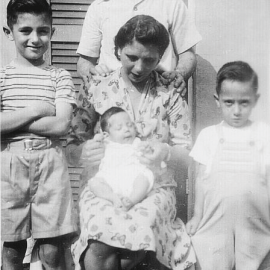

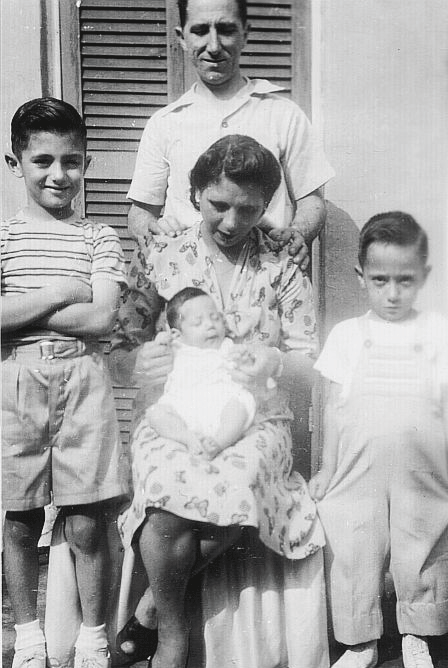

The Pente family is fairly large. His new white refrigerator can barely fit all of his family photos. There’s Pente and his three children—White Marsh resident Joe, John Jr. who lives in Virginia, and Marge from Rosedale—six grandchildren, and a whopping 14 great grandchildren.

“I’ve got the most loveable family,” he says, his eyes shining. “I brag about my family all the time. I can always depend on my family when I need them.”

Indeed, he attributes his longevity to his family. As for “secrets” to longevity, he says he really doesn’t have any, except one, so ingrained within him that he doesn’t even think of it as a secret anymore.

“There’s one thing you’ve always said that kept you young all these years,” Marge reminds him from across the kitchen table.

“Stay active,” he says, nodding. He recalls a story from when he was retiring from Western Electric, where he worked for 30 years. “They called to send off about a dozen people, all retiring. And the head director, he says, ‘I wanna tell you one thing. You’re all going out in the world. You’re all going to retire. Don’t stay home and sit in front of that television.’ I never do that. She knows I never do that,” he finishes, motioning to Marge who nods in agreement.

“I never get bored. I’m very active in this house,” he continues.

“He always likes to find something to do,” Marge says.

“I used to climb two steps at a time. Now I only climb one . . . Just wait ’til you’re 100 years old. You’ll understand.”

“I do not sit around. I like to maintain this house like I built it. I love flowers,” he gestures to his side entrance, full of brightly colored potted geraniums. “I love to stay out there and talk to people. I stay out there in the nighttime and the weekend. We have people from all over the world come down here to eat. I like to talk to them. And if the bench is broke, I’ll fix it so they can sit down.”

Besides his family and neighborhood, working has always been Pente’s pride and joy. Soon after Pente started work at the local grocery store, his father, who immigrated from the Calabria region of Italy when he was a young boy, bought a tall chair and a shoeshine box. He put them in a nearby barbershop, handed over shoe polish and two brushes to his teenage son, and told him to get to work.

“He said, ‘Make a living.’ And I went to work, and from there on, I never have stopped working,” he says.

The country was in the midst of the Great Depression when Pente graduated from Calvert Hall College High School in 1930. He put his new diploma under his arm and went job searching, eventually securing work in a factory putting handles on shopping bags. After six months, he became a foreman.

Knowing he’d need to leave to go into the defense industry to support the country’s World War II efforts, Pente went to night school for radio, and left the factory in 1941 to work at Western Electric’s Dundalk office, first making radar equipment for the war and eventually moving to its telephone switchboard division. He became a foreman there, too, barely taking a sick day—working extra unpaid hours in his basement workshop troubleshooting tiny telephone parts in order to get bonuses the next day.

He stayed at the company until his wife suffered a stroke. He took an early retirement to care for her until she died in 1975. She was only 59. More than 35 years later, he still wears his wedding ring. And he’s kept his promise to his family that things would never change.

“When my mother died, he said, ‘Everything is gonna be the same,’” Joe says. “And everybody gathers here and have for many, many years for dinners. This is the center of the universe. Small as it may be, there’s no feeling like sitting on the front steps and watching the world go by.”

The city has changed since John Pente was a young man. Towering buildings have sprung up all around Little Italy where there once was nothing. Many of the original Italian families have come and gone. The many neighborhood Jewish-owned stores that Pente used to depend on for day-to-day basics closed decades ago. But he’s never once thought of leaving.

“I have everything I need right here,” he says.

In the meantime, he’s learning to accept the limitations of old age.

“It’s not like it used to be, I admit it,” he says. “I used to climb two steps at a time. Now I only climb one at a time. Things like that.”

Right now, he’s having a heck of a time opening individually wrapped cookies—Biscoff, the kind that AirTran hands out on flights, delicious, those graham-flavored biscuits from Belgium. He received a special box of them from out-of-town relatives just in time for his 100th birthday party in April.

“My hands,” he pauses, rubbing his index and middle fingers against his thumb, “are like . . . waxy. Old age. Just wait ’til you’re 100 years old. You’ll understand.”

We laugh. One thing this man has never lost is his sense of humor.

His next birthday party is going to be his 105th, he says. And he’s expecting a Mercedes. Something he’s been requesting—always with a wink—from his children for at least a few years. Bear in mind that he hasn’t driven since his late-90s. But these are details to be saved for a later date.

His plans for the rest of the day are casual. Sit with his son. Marge may stop by again. Maybe he and Gina will go outside and hang with the guys for a little while. He might nap if the urge hits him.

One thing’s for sure, though. He will be here. And if you stop by even just a few times, he will quickly make you feel like part of the family.

“We’re always glad to see you,” he says, as we part ways. “Come back anytime. And if you want to make a reservation on the bench,” he adds with a smile, “lemme know.