News & Community

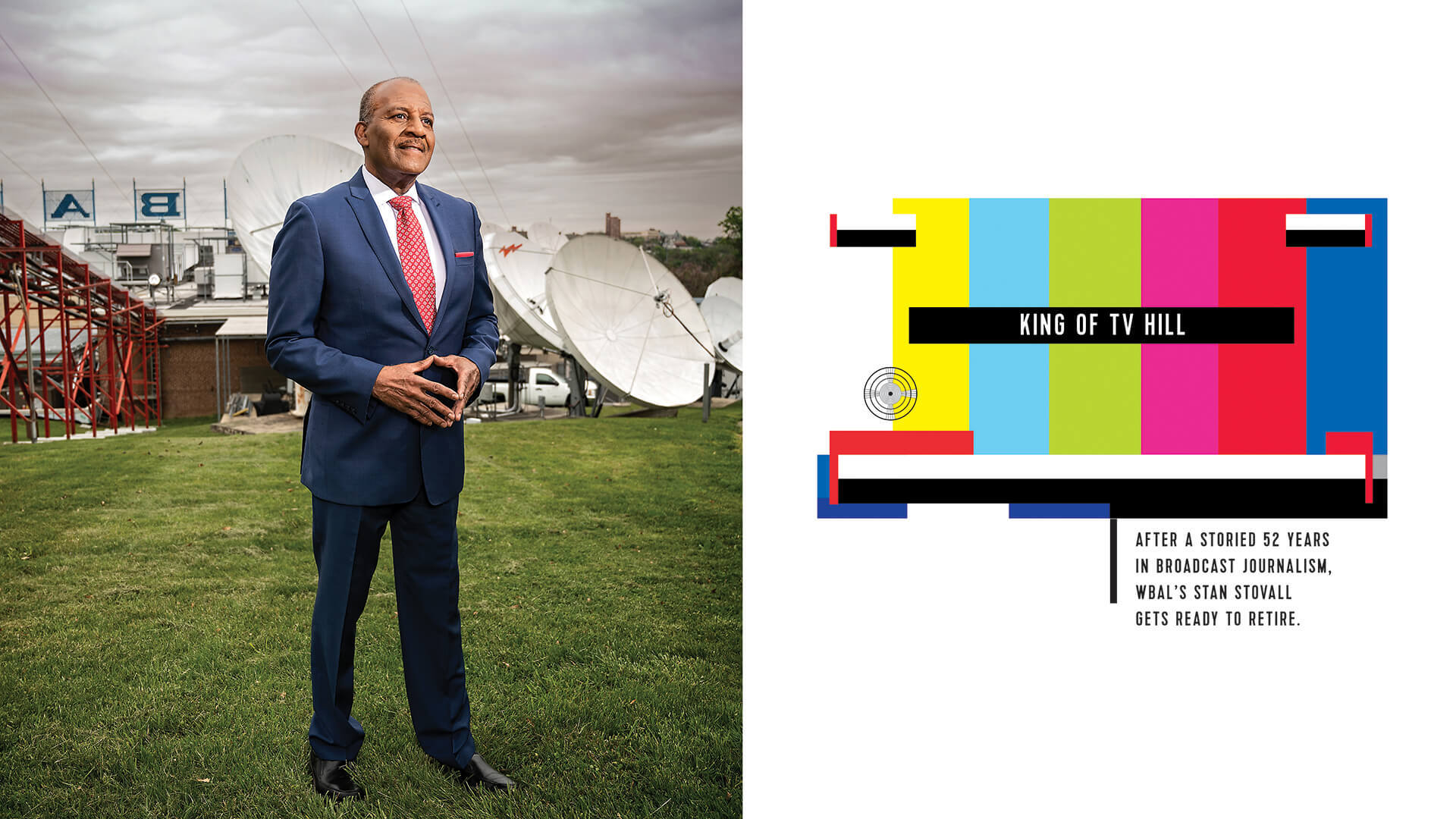

King Of TV Hill

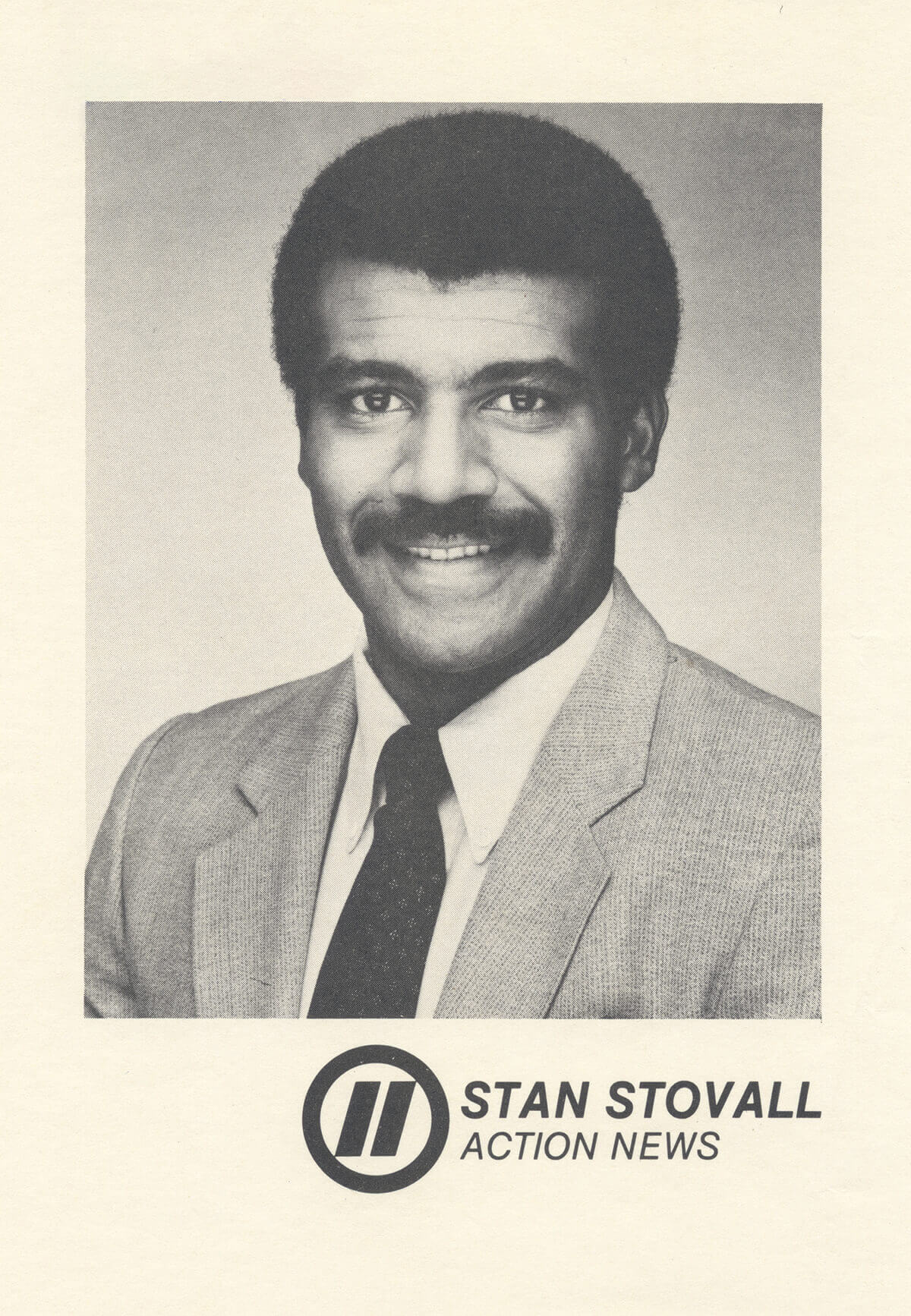

After a storied 52 years in broadcast journalism, WBAL’s Stan Stovall gets ready to retire.

By Jane Marion

Photography by Christopher Myers

THE FIRST TIME STAN STOVALL WALKED INTO THE NEWSROOM

at WBAL in April of 1978, he was 25 years old—a young hotshot, who had quickly risen through the ranks of broadcast journalism. He had a natural knack for reporting, made-for-TV baritone, and eight-and-a-half years of on-camera experience, thanks to breaking into the industry while still in high school. When he stepped into the studio on Hooper Avenue, the gig was Stovall’s first role as a weekday primary anchor—it was the moment he had been working for.

After signing off for a final Saturday night broadcast at KSDK-TV in St. Louis, Missouri, he was on-air in Baltimore the following Monday, having barely enough time to practice learning how to say the name of his newly adopted city. “I had to learn to say Bal-ti-more, not Bal-tee-more,” he recalls. After all, Stovall had grown up in Arizona, a long way from the Mid-Atlantic.

“When you move to a new town, you try to find out everything you possibly can, so you don’t look like you’re lost in the candy shop,” says Stovall. “But I didn’t do my research before I got here. I remember that first Tuesday was election night and Paul Sarbanes was running for senator. The first time I said his name, I said ‘Sar-ban-us,’ and Ron Smith, my co-anchor at the time, laughed out loud on the air.”

Decades later, Stovall is having the last laugh. At 69, the venerable Emmy Award-winning journalist, one of the most beloved anchors in Baltimore, will hang up his mic for good toward the end of the year. He has spent roughly half of his career on TV Hill—the mini media neighborhood where the station is located north of Woodberry—for a combined total of twenty-six-and-a-half years.

“I’ve had a chance to think about my impending retirement,” says Stovall, sitting in a WBAL conference room. “When I signed this contract two years ago, I knew it would be the last. I wanted to hit that 50-year milestone, which I did in June of 2020—that was my primary motivation for staying in the business, because I knew that for an African-American news anchor, I might be the only one to have lasted that long.”

S tovall was born in 1953, in Rochester, New York. His mother’s family was from upstate New York, a place he remembers as fairly integrated. His father’s family was from Birmingham, Alabama, one of the most racially discriminatory and segregated cities in the country at that time. In 1958, Stovall recalls visiting his great-grandmother on her deathbed there and seeing the Jim Crow South for the first time.

“The deeper we’d go into the South, we’d start seeing Confederate flags, which I didn’t understand,” he says. “Once we entered the city limits, that’s when I saw ‘Whites only, no Blacks allowed’ signs, whites-only drinking fountains. This side of town had sidewalks and streetlights, the other side of town had dirt roads...Even at age five, it slapped me in the face, and I started to become aware of racism, prejudice, and segregation.”

When Stovall was eight, his family hitched a trailer to their ’61 Chevy Impala and moved to Phoenix. At the time, the state was only 2-percent Black, and the Civil Rights Movement was in its infancy. He and his younger brother, Darrell, were almost always the only Black students in their elementary and junior-high schools. “I caught hell, my brother caught hell,” he says. “Not a day went by in school that I wasn’t called [the N-word].”

Stovall behind the anchor desk with Ron Smith at WBAL, Studio 10A, 1979.

His glasses and strong New York accent only made matters worse, and he sometimes endured physical abuse. “I got picked on mercilessly,” he says, “and among the few Black friends I had, I was told ‘You’re trying to be white,’ because I spoke good English, so I caught it from both sides.”

Rather than fight back, he learned restraint from his parents, who followed the teachings of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and preached nonviolence to their boys. “I let it bounce,” says Stovall, whose steely stoicism likely helped him report the news objectively in the years to follow. “The mantra in the Black community was that to have a fair shot at life, you’ve got to be twice as good as anyone else—meaning whites. To get a shot at doing well in school or getting a job was through education. I took that to heart at a very early age and ran with it.”

Across the country, the civil rights battle continued to roil, and Stovall gradually woke up to the world around him. In 1963, his aunt’s church, the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, which had served as a civil rights meeting spot, was bombed by the Ku Klux Klan, killing four young Black girls. She had been their teacher. “I started paying much more attention to the images I was seeing on TV every night, what was going on in the South, the protest marches, the beatings, the water hosings,” says Stovall.

Before that pivotal moment, he was already on his way to becoming a lover of language. His mother, who became the first African-American salesclerk at the local Woolworth’s (after organizing a picket line along with the local chapters of the NAACP and the National Urban League to desegregate hiring practices in the downtown), encouraged her sons to read. And Stovall’s favorite pastime was poring through the World Book encyclopedia in his quest to learn more about the world around him. “I’d always been curious,” he says. “I always knew there’s something bigger than this town I’m working in or this state—or even country.”

That inquisitiveness led Stovall to his first “print” job, when he became a paper boy at age 10. “I threw the morning paper, The Arizona Republic,” he says. “I’d get up at 4 a.m. to go on my bike and pick up my papers. I’d ride around the neighborhood and get home just in time to get ready to walk to school.” In addition to delivering the newspaper, he read it, too. “Even then, I realized that reading the newspaper every day and watching the news helped me be a much better student,” says Stovall.

Publicity photo of Stovall and the news team in his early years of broadcasting.

Several years later, Stovall landed his first “broadcast” job—reading the cafeteria menu and school announcements on closed-circuit television in the seventh and eighth grades. Later, at Carl Hayden High School, Stovall was a scholar and star athlete, earning straight As and serving as captain of the football, basketball, and track teams. By senior year, he was elected class president—a position he ran for, and won, to cure himself of a fear of public speaking.

At 17, as class president, he attended the Arizona Boys State program to learn how to be a more effective student leader and ended up with a summer journalism job when Ernest W. McFarland, a TV executive (and former Arizona governor) from KTVK-TV, the local ABC affiliate and sponsor of the program, heard Stovall’s speeches and was so impressed that he hired him for a summer stint. “They paid me $1.30 an hour, and I was happy to get it,” he recalls. That job made him the first African-American TV reporter in the Grand Canyon State.

Though he blew his first assignment covering the opening of a new theme park—he was told to document the ribbon-cutting with a silent-film camera (video had not yet been invented) but had no idea how to operate it, resulting in no footage—Stovall soon became a quick study, shooting his own footage, writing his own copy, and editing the final product. In June 1971, the day after he graduated from high school, McFarland offered him a job. By the time he turned 18, he was the youngest TV news anchor in the country.

His big break came not only because of his oratorial skills but because the Federal Communications Commission was putting pressure on TV stations to diversify their staffs after the death of Dr. King. “Cities were going up in flames,” says Stovall. “It had to change. The FCC said, ‘Integrate your staffs or we’re going to yank your license to operate and put you out of business.’”

By 1971, Stovall was also a full-time student at Arizona State University. “Three days a week, I would go to school at 8 in the morning, until 12:30, and I was due on the job at 1 in the afternoon,” he says. “I’d rush to work, go and crank out one story for the early evening newscast at 6.” Impressed with the fledgling journalist, the station also made him a weekend news anchor—he was a one-man band juggling multiple stories at a time, including sports and weather.

After just two years on the job, he was live on-air, hosting newscasts at 6 and 10 p.m.

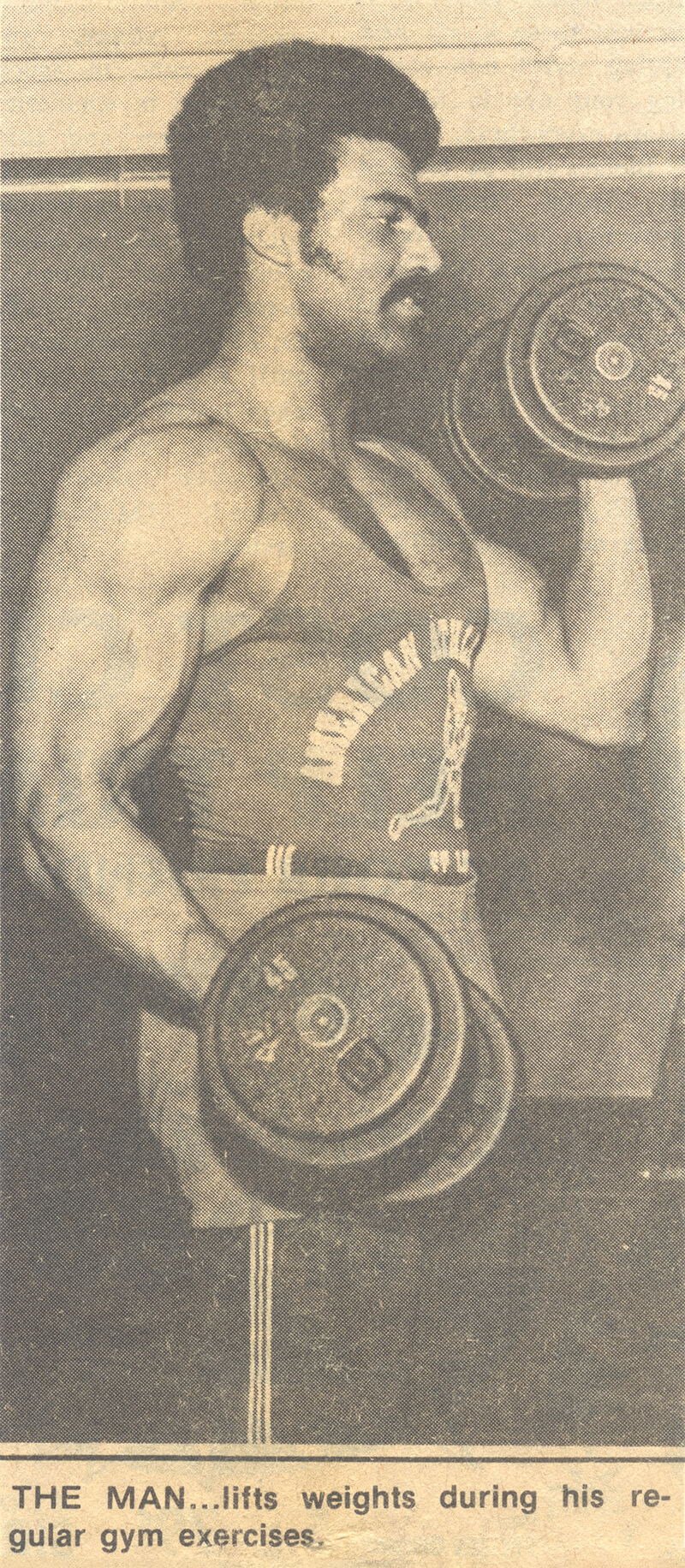

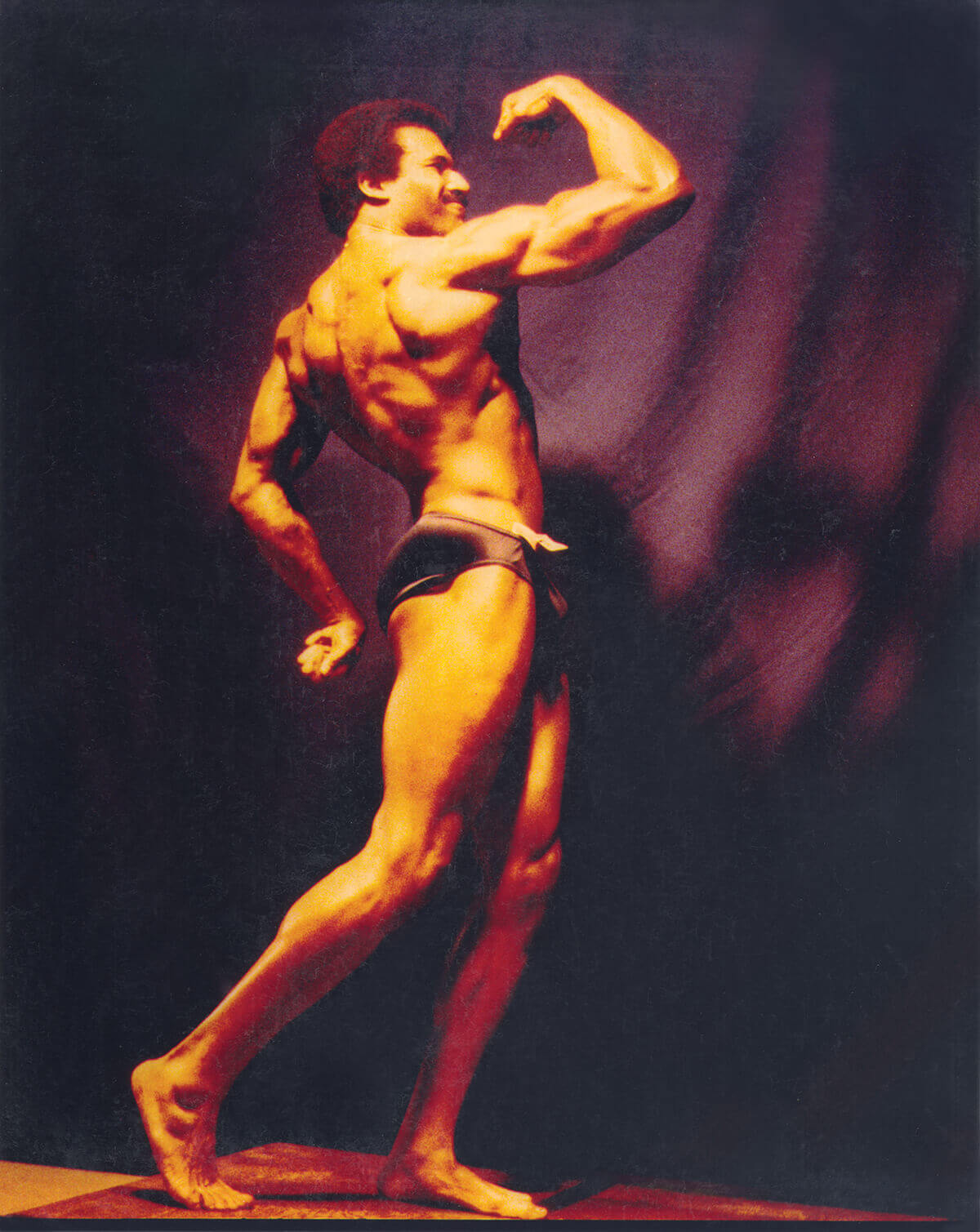

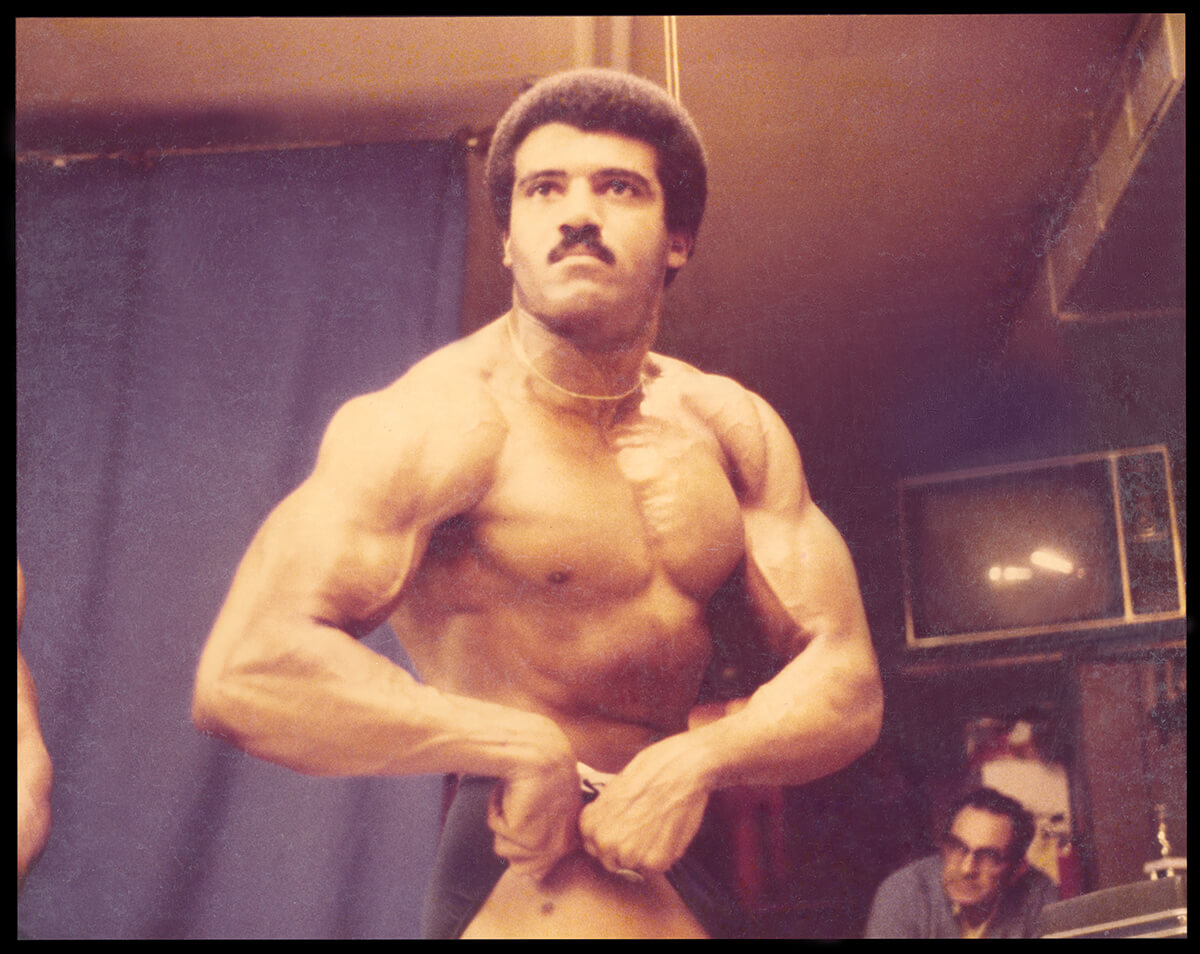

Newspaper clipping of bodybuilding.

In his off-camera hours, hoping to try out for the college football team, Stovall lifted weights at the local YMCA where five record-holding professional powerlifters trained. One of them, Pat Neve, recognized him from the news and took him under his wing as his training partner. The natural athlete excelled and began to compete in the sport—he never did join the football team but continued to lift iron. In all, Stovall is a four-time State Powerlifting Champion and holds the bodybuilding titles of Junior Mr. Arizona, Mr. Maryland, Mr. South Atlantic, and Mr. Delmarva.

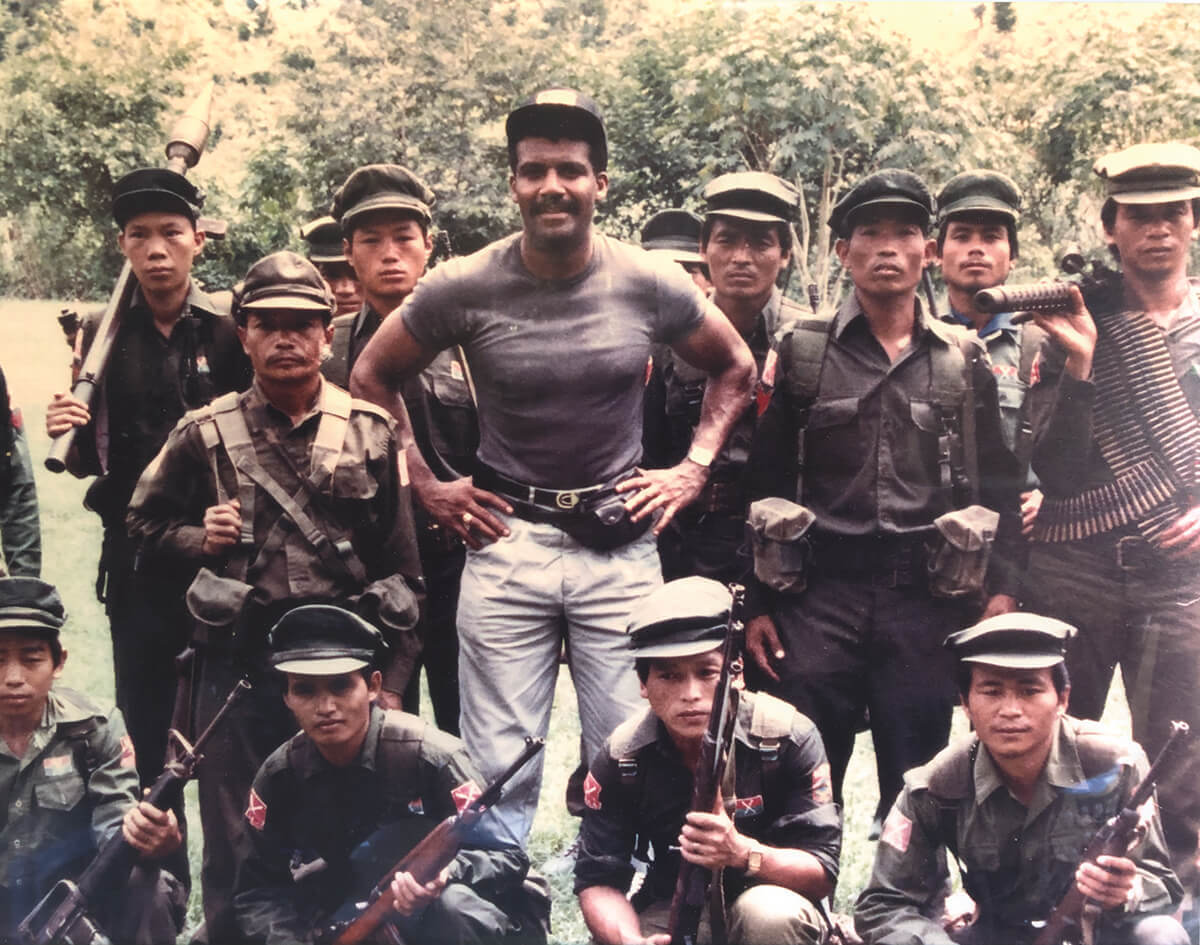

After KTVK, he continued his upward trajectory, moving to bigger markets and more prominent roles. Stops along the way included KSD-TV (now KSDK-TV) in St. Louis, Missouri; his first tour of duty at WBAL (where he stayed for six-and-a-half years and became the first African-American male primary weekday news anchor in the station’s history); a move back to KSD-TV, where he won an Emmy Award for the Best Television News Anchor in 1985 for a series of exclusive reports on the Contra War in Nicaragua; and a job as a weekday primary anchor at the CBS affiliate in Philadelphia, the nation’s fourth-biggest media market. In all cases, he anchored in coveted time slots and helped the station achieve number-one ratings.

He also freelanced overseas, working in Asia for a stretch while covering the Burmese civil war and living in a jungle combat zone with rebel forces. By 1989, he was back in Baltimore for a second time, where he joined WMAR, working there for 13 years. He and his 6 p.m. co-anchor, Beverly Burke, were not only number-one in the ratings, but the first African-American male and female primary newscast co-anchors in the country.

In 1993, Stovall’s career was almost cut short when he was diagnosed with glaucoma, a disease he continues to battle. When it was discovered, he had already lost sight in his left eye. “I broke down for a short period of time,” he says. “I was blind in one eye and losing sight in the other eye—I could be blind tomorrow and then where am I going to be? I cried for a couple of days and then thought, I have work to do. While I still have one good eye, let me plug through with medications and eyedrop therapy to maintain the sight.”

Stovall has worked with one functional eye ever since, but by 2020 it had taken its toll. Last year, he had surgery to alleviate the pressure on the optic nerves in his right eye. “My good eye was wearing out from doing the work of two eyes under the bright studio lights,” he says. “I was having difficulty seeing without glasses, and I knew my time was finally running out”—that’s when he told WBAL GM Dan Joerres he was ready to retire.

Covering the Burmese civil war and living in a jungle combat zone with rebel forces in 1988.

Another challenge came in 2001, when WMAR—which had changed ownership, network affiliation, and programming, including jettisoning ratings juggernaut The Oprah Winfrey Show for The Rosie O’Donnell Show as a lead-in to the 5 p.m. news—tried to cut his pay as the station slipped in ratings. After being a rising star for so long, this was an unexpected detour.

“In this business, when the ratings are great, the anchors get a lot of credit for drawing in the audience, especially the senior anchor,” says Stovall. “But when the numbers go bad, the senior anchor, who is typically making the most money, takes the hit. The writing was clearly on the wall, so I chose to leave.”

Due to a non-compete clause, Stovall was unable to work as a broadcaster for a full year in the state of Maryland, but he wanted to stay in the city he’d considered home, forcing him to juggle three jobs to make ends meet and provide for his wife and their three children. “It was a humbling experience,” he says. “I’ll admit that maybe I even got a big head because of all the success in the industry at that point. This certainly brought me back down to earth, to the reality that sometimes, no matter how hard you work, or how successful you are, things just don’t work out.”

“I WAS HAVING DIFFICULTY SEEING WITHOUT GLASSES, AND I KNEW MY TIME WAS FINALLY RUNNING OUT.”

But in April of 2003, he got another break when then-WBAL President and GM Bill Fine created a position—as co-anchor of the weekend morning newscasts—specifically for him.

“I told Stan, ‘I could use some help on the weekend morning anchor desk, but it’s a fraction of what you made in your heyday,’” Fine recalls of their conversation after a chance meeting. “He said, ‘Bill, I’m currently making zero as a broadcaster. Try me.’” Fine shared his concerns: “I told him, ‘It’s complicated. People remember you from the old days. You left this image that you’re this bigger-than-life anchorman and can be very hard to manage.’” Stovall allayed his fears. He recalls Stovall saying, “‘I’m not that guy—what I’ve been through [at WMAR] is as humbling an experience as someone can have, I’m ready to earn my way back.’”

And earn his way back he did.

Stovall anchored those weekend morning newscasts and within three weeks, he took the show to number-one ratings. He was soon promoted to the weekday morning newscasts, as well as the weekday noon newscasts—plus the station’s public affairs show, 11 TV Hill. A month later, he was promoted again, working a split shift on the 11 News Today at 5 a.m. and the 11 News at 5 p.m. Ratings success followed whatever he anchored. In 2012, when veteran news anchor Rod Daniels retired, Stovall stepped in to co-anchor the weekday 5, 6, and 11 p.m. newscasts with Donna Hamilton.

“I got the best of Stan Stovall,” says the now-retired Fine. “For all his illustrious career, I got Stan after he had learned all the lessons of journalism and humility. And as much as others thought I was taking a chance, I didn’t. I was convinced that Stan was a lock for us. The beauty of Stan is that he had God-given gifts—his presence, his communication skills, his commanding voice, and ability to communicate at an early age.”

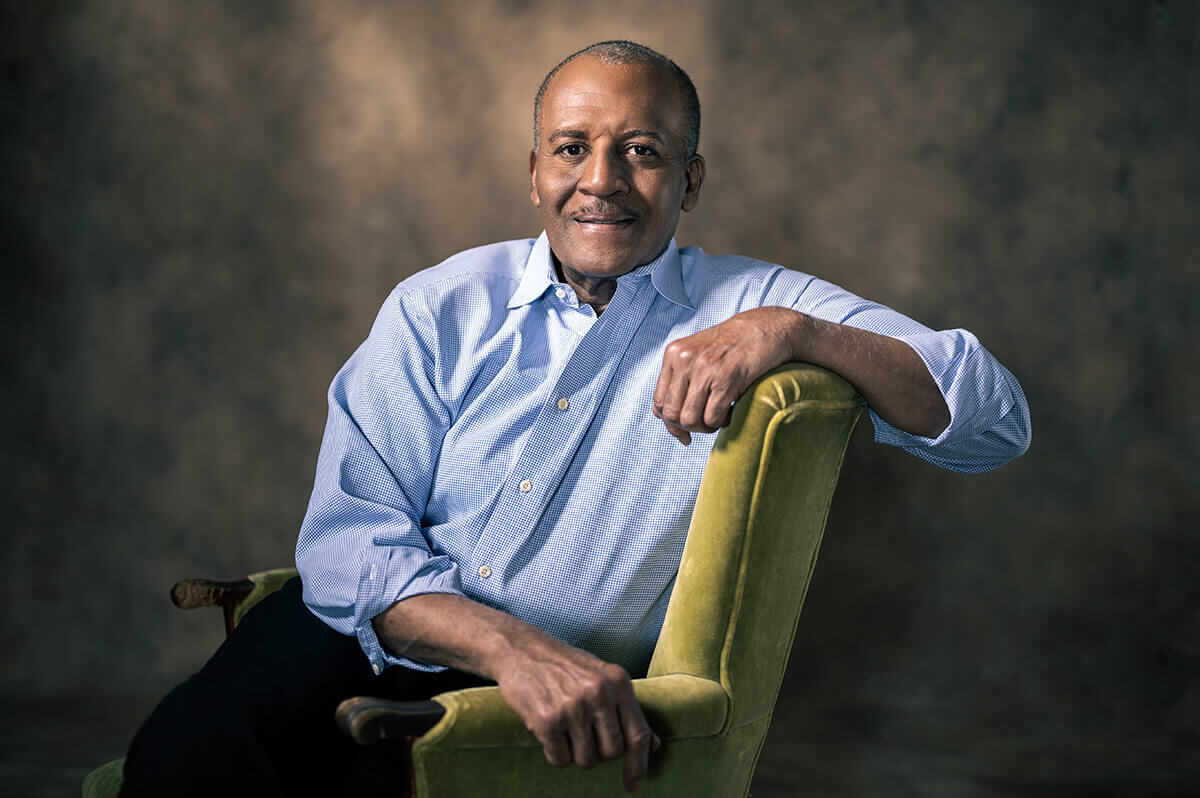

Stovall today.

T hroughout Stovall’s career, there have been many memorable moments, including being in a boxing ring with Muhammad Ali, interviewing President Richard Nixon when he was running for re-election in 1972, traveling to Rome in 1994 to cover the elevation of Baltimore Archbishop William Keeler to the Catholic Church College of Cardinals, and covering the inauguration of Barack Obama in 2009, an experience that moved him to tears on camera.

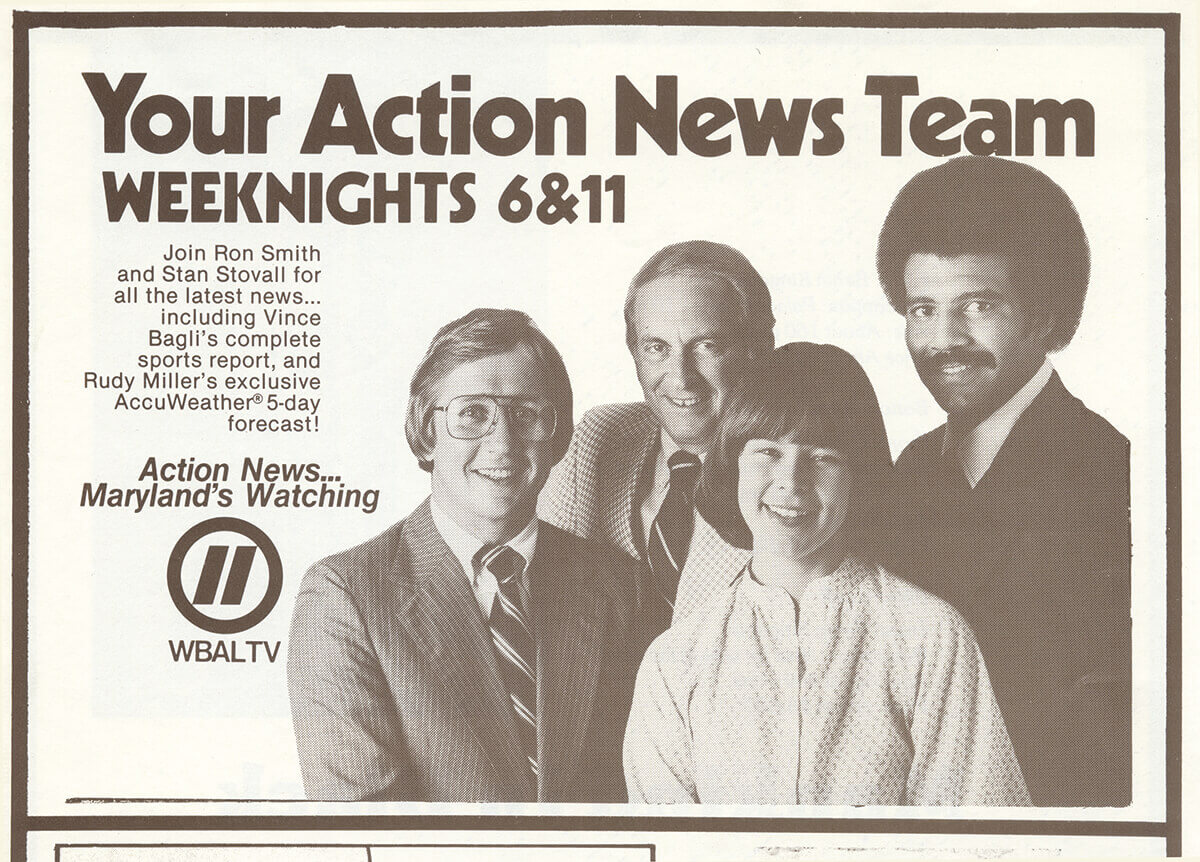

11 Action News publicity photo, 1983.

“I grew up my entire life thinking we will never see a Black president of the United States,” he says, his voice still catching with emotion. “In that moment, when he’s taking the oath of office, I’m in full-blown tears. I’m standing there reporting live and I was so touched by the fact that, in my lifetime, I saw this happen, and that I had the opportunity to be there—it was significant for me.” Another pivotal reporting moment came closer to home. He was a literal anchor in the storm, providing calm, steady coverage during the Baltimore Uprising following the death of Freddie Gray in 2015. With absolute authority, Stovall ad-libbed on-air for hours on end, carefully delineating the difference between rioters and peaceful protesters, while, in the heat of the moment, many reporters were lumping everyone together. “My job wasn’t to be in the middle of it but to anchor it from the studio,” he says. “I felt very strongly that it was important to try to help de-escalate the situation with accurate information. I don’t want to castigate my coworkers, but when you are in a situation like that, where it can be very volatile, oftentimes your emotions get the best of you, and you bypass accuracy.”

This kind of grace under pressure is why WBAL chief investigative reporter Jayne Miller, who started at the station roughly 16 months after Stovall, is grateful to have spent so much of her career as his colleague. “When you’re in the field as a reporter on-air, you always want to know that the person on the other end of the earpiece being the anchor is reliable—and Stan is the reason they call them ‘TV anchors,’” she says, pointing to the night she was in the field when homicide detective Sean Suiter was found shot in the head in an alley in West Baltimore.

“That was one of those breaking news on the air with no definite end-time situations,” says Miller. “And in those situations, where you’re on the air continuously with a developing and breaking story, it is vital that you have an anchor who knows what he or she is talking about and is really good at maintaining coverage. With Stan, you can always rely on him to be informed of the latest development and ask the right questions. People underestimate how hard that is.”

Stovall has set himself apart in other ways, as well. He doesn’t do social media, instead preferring to do things the old-fashioned way. “I go out to speak to every school and church, civic group, and police organization, I don’t need social media to do that,” he says. “I am doing it in person, and I’ve been doing it that way since day one. You can put up all the billboards and placards on the sides of buses promoting your news team, and it’s just not as effective as me shaking your hand and saying, ‘How are you doing?’ I’m OG—I’m an original gangster when it comes to doing TV news—and I haven’t strayed from that.”

Stovall is a four-time State Powerlifting Champion and holds four bodybuilding titles, including Mr. Arizona and Mr. Maryland.

I ndeed, on a brisk day in February, Stovall makes an appearance at the Greater Baltimore Medical Center in conjunction with Black History Month. “Ever since Gerald Ford officially recognized Black History Month in 1976, I’ve probably done at least 100 Black History Month speeches,” he tells the crowd. “This might be the last Black history speech I do, so I felt the pressure to make this one very meaningful.”

“THE BEAUTY OF STAN IS THAT HE HAD GOD-GIVEN GIFTS.”

In a room filled with doctors, nurses, and hospital administrators, Stovall gives a stirring speech, moving through the civil rights era, the Black Lives Matter movement, systematic racism, and the ways in which U.S. history has glossed over Black history, saying that if schools did a better job, there would be no need for such a designation.

“In grades three through eight, we were taught all the great things that white people did for America,” says Stovall. “All the great presidents, all the white adventurers and discoverers, all the great scientists, and inventors. But the only thing we heard about Black people’s contribution to America were in terms of slavery and working on the plantations—like that’s all Blacks were capable of doing, because they were somehow innately inferior. I can’t tell you how embarrassed, uncomfortable, and demeaned I felt when kids in the class would look at me like I was somehow not as smart as them.”

A vintage WBAL Action News advertisement.

On this day, the anchorman wears a blue suit, an African kente tie, and matching pocket handkerchief, which he also wore at a Black History Month speech while working at WMAR in 1989. “It was late in the afternoon, so I went directly from the speech to the station and wore it on the air for the 5, 6, and 11 o’clock news,” Stovall tells the crowd. “The floodgates opened as soon as I got off the air. People were calling in and writing letters complaining that by wearing this tie and hankie in 1989, in Baltimore, Maryland, I was playing the race card, that I was stirring up racial tensions just by wearing something that represented my pride in my African culture.”

As he moves toward the finish line, Stovall is deeply reflective. “African Americans have made so many gains just in my lifetime,” he says. “Yes, it has improved but those freedoms that were hard fought to gain are gradually and very actively being eroded in this country,” he says. “It’s probably just as racially divisive now in 2022 as it was when I was a kid growing up in the 1960s—and that is so disheartening.”

He has long considered himself a change-maker, and his work as a vehicle for progress, but today, before this crowd, he wonders aloud if he’s done enough. He takes it personally. “I can’t help but think, ‘Wasn’t part of my job all these years supposed to be about helping to continue to move America forward?’” he asks. “Did I lose touch? How did we get here? I’ve been a part of reporting it for 50-plus years and you can see it happening right before your eyes—and you’re powerless to do anything about it.”

Weeks later, in mid-March, Stovall is at the station getting ready for the evening news. These days, since his retirement announcement, he oversees only the weekday 6 p.m. broadcasts. As he delivers the news, in between live shots, the ever-prepared journalist reviews the script on his iPad before reading it on-air from the teleprompter.

It’s hard to imagine him in any other career—in fact, he even played a reporter in Chris Rock’s Head of State—and even harder to imagine anyone filling his shoes. He’s a total pro, shifting seamlessly from the war in Ukraine to soaring gas prices to chatting with co-anchor Ashleigh Hinson about Jayne Miller’s Lifetime Achievement Award gala in Washington, D.C. “We were all kids when we walked in the door here,” he says to Hinson. “I was 25. Jayne was 24.”

Earlier in the day, he edited his script for clarity. “I’m looking for good sentence structure,” he says. “I’m making it easier for the viewer to understand. I simplify the copy.”

When new information comes in or a story is updated, he makes sure that he’s not reading the copy on-air for the first time. “The hardest thing to do is a cold read,” he says. “The bottom line is that you’re the one in front of the camera, so if there’s a mistake at home, people don’t say, ‘Oh, that producer messed that up,’ they’ll say, ‘Stan messed that up,’ so it’s always a matter of covering yourself.”

One big flex

At this point, about the only thing Stovall hasn’t really prepared for is retirement. “People ask me all the time, ‘Are you going to stay in the area?’ I’m not sure,” he says. “But I do know this. I’m not the kind of person who will sit home in a rocking chair. I’ll be training till the day I die—I will still get my workouts in, I still feel like I have something to offer in the communications world, I’ll probably shift my emphasis to doing commercial work voiceovers, books on tape, maybe movie work...”

Regardless of his next move, he’ll go out on top, which in TV news means dominating the ratings. In fact, every newscast that Stovall has anchored since his return to WBAL 20 years ago has gone to number one, a fact that fills him with pride. “I made Bill Fine look good,” says Stovall with a chuckle.

Fine concurs. “Stan Stovall is on my list of best hires I’ve ever made,” he says. “Stan deserves to be at the top of the list—or close to it. He came in as a weekend morning anchor and is going out as the longest-reigning, undisputed king of Baltimore TV.”