History

◆

IN THE SPRING OF 2023, AN UNEXPECTED EMAIL ARRIVED

at Afro Charities, the nonprofit arm of The Baltimore Afro-American newspaper. The Maryland Center for History and Culture had recently learned that a set of worn, wood-and-glass doors which had once served as the entrance to the offices of The Afro and the Baltimore chapter of the NAACP—as their chipped but mostly legible etched panes indicated—were headed to auction in the Shenandoah Valley.

The 92-inch doors represented more than a potentially unique restoration project for a buyer. Stepping through their threshold would have been the likes of W.E.B. Du Bois, Thurgood Marshall, Romare Bearden, and Lillian Mae Carroll Jackson, not to mention Carl Murphy, the newspaper’s visionary publisher from 1922 to 1967. Largely forgotten today is the groundbreaking collaboration between The Afro and the NAACP, who often worked in concert, exposing racial violence and challenging segregation and Jim Crow in the media as well as in the courtroom. It is a partnership that the Maryland Center for History and Culture understood, however. They alerted the small team at Afro Charities, which oversees the paper’s 134-year-old archives, about the auction and the possibility of acquiring the find.

Deyane Moses, the director of programs and partnership for Afro Charities, did a deep dive into the archives to authenticate the doors. Soon enough, Afro publisher Frances “Toni” Murphy Draper and her husband, Andre Draper, the paper’s director of operations, were driving though the cornfields of Rockingham County, Virginia, to the auction house of Jeffrey S. Evans & Associates. The full provenance of the doors is not clear, though at some point they ended up in a salvage yard.

“You know the saying,” Toni Draper recounts with a laugh. “One person’s trash, another person’s treasure.”

Not only is Carl Murphy her grandfather, but John Murphy Sr., the founder of The Afro-American, a man born into slavery, is Draper’s great-grandfather.

The couple made it to Evans & Associates an hour before they closed on a Friday evening before Saturday’s live auction—an event they had never witnessed in person. The friendly team there allayed some of their anxiety and offered advice about how to respond if bidders pushed up the price of the doors, which had begun garnering interest from a regional art and antiques publication.

“The staff seemed to be as happy as we were to make the connection between the doors and the history behind them,” Draper says. “They were telling people the next day that these were our family’s doors, which was one of the things that made the whole thing so fun. It was like what you see on television and in the movies. People are bidding in the room and online and on the phone all at once and the auctioneer is talking at the pace that we all have heard, ‘Going once, going twice,’ and I’m just like, ‘My God.’”

Earlier, a historical scrapbook had sold for $10,000, which made them nervous, but after the price for the doors topped $4,000, the bidding stopped—and The Afro had them back, as well as a tangible gateway to their past.

“It was such a moment,” Draper says. “Thurgood Marshall used to walk through those doors and meet with my grandfather to use him as a sounding board.”

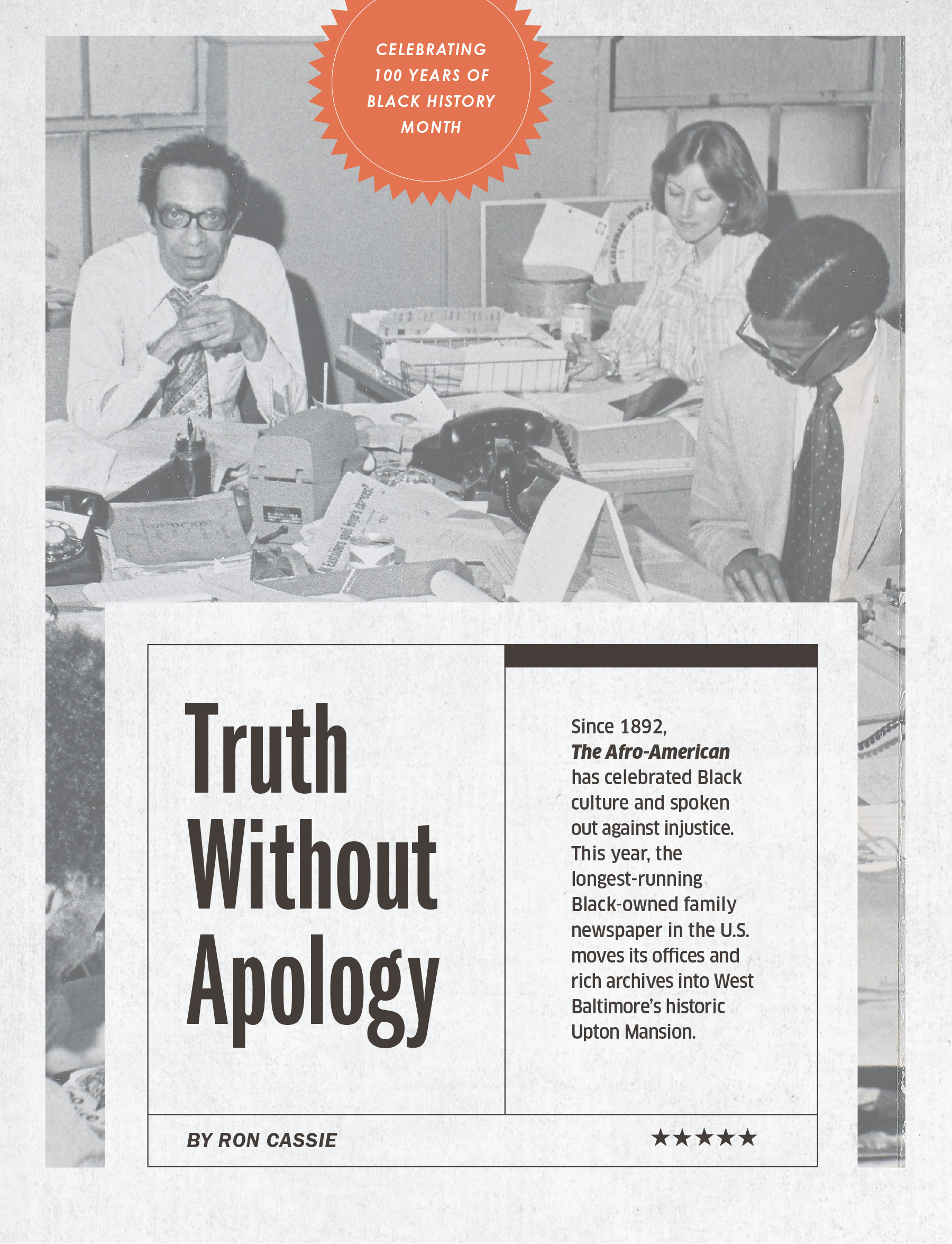

OPENING SPREAD:

Reporters and editors

at the City Desk of

The Afro-American

in 1975.—Courtesy of the Afro-American Newspaper Archives

(Left to right): Megan McShea, archival consultant at Afro Charities; Joshua Earl, registrar at Jeffrey S. Evans; Savannah Wood, executive director of Afro Charities; Deyane Moses, curator of archives at Afro Charities; and Tyrone Jones, imaging specialist at Maryland State Archives; with the former Afro doors, which were reacquired in 2023.—Courtesy of Afro Charities

THE AFRO-AMERICAN BEGAN as a Saturday weekly on Aug. 13, 1892. At its outset, the paper concentrated on the happenings of its immediate, booming, West Baltimore environs, where the Black population leapt from roughly 50,000 to almost 80,000 residents in the last two decades of the 19th century. Eventually, it became one of at least six Black newspapers in the city vying for readership.

The longest, continously running Black-owned family paper and one of the oldest Black-owned businesses in the U.S. today, The Afro's beginnings in the aftermath of Reconstruction—and its staying power—are almost impossible to wrap one’s head around. Five years after its launch, with its then-owners struggling amid competition and juggling other business interests, the newspaper filed for bankruptcy. To the rescue? Murphy Sr., who had earned his freedom fighting under Grant and Sherman in the 30th Regiment Infantry of the U.S. Colored Troops. After managing The Afro's print department for a time, the 56-year-old had recently started publishing a one-page Bethel A.M.E Church weekly called the Sunday School Helper. With $200 borrowed from his wife, Martha, also born into slavery, he purchased The Afro's name and equipment at auction and merged the paper with his Sunday School Helper.

Family volunteers staffed the enterprise at first, but by the 1920s, The Afro-American had grown to nearly 100 employees. It’s often said newspapers are the first drafts of history, but that description shortchanges the role The Afro played in the events of the day. By bearing witness to an Eastern Shore lynching, as a young Afro reporter named Clarence Mitchell Jr. did; commissioning Langston Hughes to cover Black volunteers fighting in the Spanish Civil War; sending a female correspondent overseas to cover Black units in World War II; and with its journalists risking their lives to cover civil rights battles in Little Rock, Arkansas, and Montgomery, Alabama, The Afro did not merely chronicle the injustices of the day, it was embedded in those struggles. Behind the scenes and on its editorial pages, The Afro crusaded for racial equity and economic advancement. In Baltimore’s Black community, The Afro served as both the public square and paper of record.

Remarkably, The Afro-American is not only still in operation but thriving, publishing weekly in print and daily online, earning recognition as one of the best Black news websites last year. And, a major transformation is scheduled for the end of this year. Currently in the middle of a $16-million overhaul of the long-vacant Upton Mansion in West Baltimore, The Afro is moving its offices and invaluable archives—the foundation of its new Martha E. Murphy Research Institute—back to the neighborhood where the paper was born. (Listed on the National Registry of Historic Places and situated on a hill overlooking an otherwise struggling neighborhood, it’s hoped the facility will serve as an anchor institution.) Called MEMRI for short, an appropriately homophonic acronym, the research center honors Martha Murphy’s $200 investment in The Afro's original printing equipment and her contributions to the city, which included co-founding the Baltimore Colored Young Women’s Christian Association.

“We estimate that there are more than three million photographs in the collection, not all of which were published, which usually gives people a sense of the scale of the archive,” says Savannah Wood, the executive director of Afro Charities and a fifth-generation descendant of the paper’s founder. “But that’s just the photographs. Then there are thousands of letters. And the actual bound volumes of the newspapers themselves, which date back to the 1910s.”

There are also pamphlets from civic meetings, annual fiscal reports, yearbooks, programs, newspaper cartoons, and reporters’ notebooks, which, in some instances at least, are truly the first drafts of history.

Not too long ago, a recording disc titled “Thurgood Marshall” was discovered, which turned out to be a strategy session between the legendary NAACP Legal Defense Fund attorney and Carl Murphy about the Brown v. Board of Education case.

Some may think of a Black press archive as having a narrow concentration, Wood continues. That maybe it is just about Black people, or just about Baltimore, for example. But The Afro, she notes, produced editions in multiple cities, including Philadelphia, Newark, New Jersey, Richmond, Virginia, and Washington, D.C., plus a national edition, and dispatched its reporters all over the world, providing a Black perspective on global affairs from the Caribbean to Africa and across Europe. (Of special note: Afro journalist Mabel Grammer used her platform to create the “Brown Baby Plan” in post-World War II Germany, which led to Black families back home adopting hundreds of mixed-race boys and girls who faced discrimination.)

Nearly all The Afro's historic print editions, some dating to the 1890s, are now digitized and searchable with an Enoch Pratt Free Library card in Baltimore. Other files, ephemera, and artifacts are still being inventoried and uncovered—like the doors, which will be on display at the new MEMRI archives and reading room—expected to open to the public in early 2027.

“One of the most important things to share, I think, is that no matter where somebody is from, what their background is, there is likely a connection for them in this collection,” Wood says. “If you are not from Baltimore, if you’re from Sweden, there are stories about Sweden. There are things that will relate to everyone’s life in this collection. It is a kind of a magic that is in the archive.”

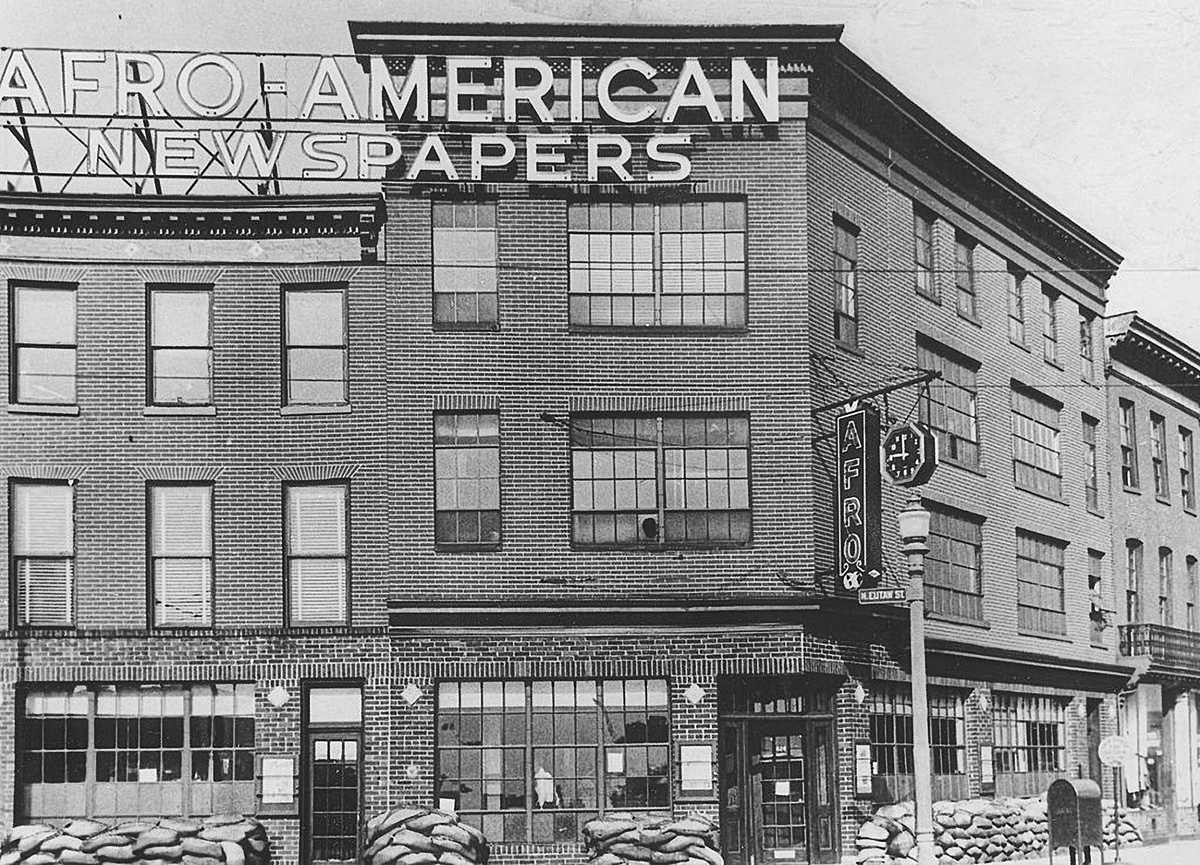

The exterior

of The Afro-American

newspaper building,

c. 1935.—The Afro American Newspaper/Gado/Getty Images

CARL MURPHY WAS TEACHING and serving as chair of the German language department at Howard University in 1918 when his father sent word that he was needed in Baltimore. The time had come to return home and work for the family paper.

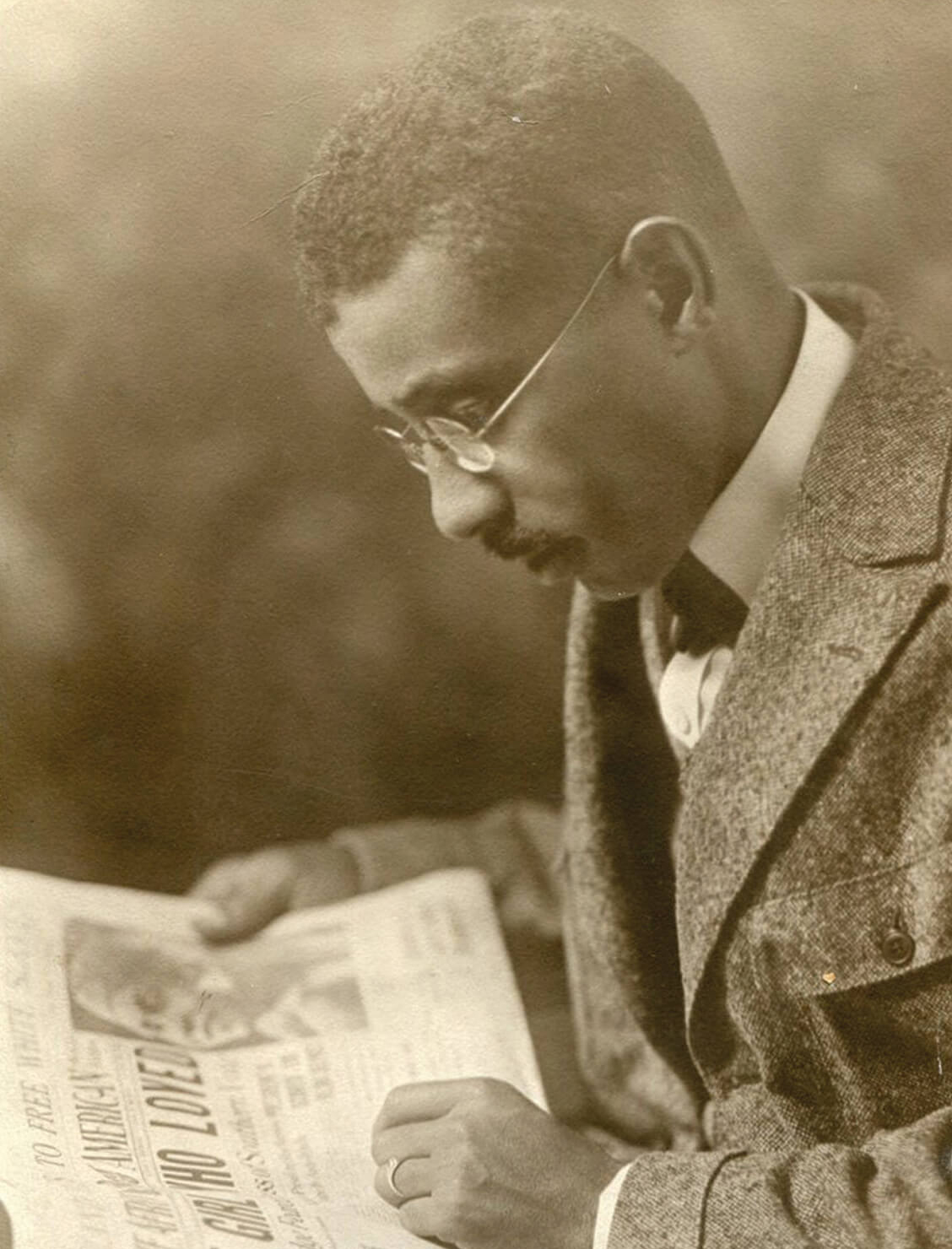

A portrait of visionary

publisher Carl Murphy. —Courtesy of The Afro American Newspaper Archives

Four years later, John Murphy Sr. died and the surviving Murphy clan elected Carl to fill the shoes of The Afro founder in his role as publisher and chief editor. A graduate of Frederick Douglass High School, and Howard and Harvard universities, the younger Murphy immersed himself in his new career, learning every aspect of the newspaper and publishing business.

Under Carl Murphy’s leadership, The Afro-American became the largest circulating Black newspaper on the East Coast, and one of the most influential and financially successful Black newspapers in the country. He hired the best writers, photographers (see "The Daily Hustle," on the photographs of I. Henry Phillips Sr., below), and artists, including the renowned Bearden, who served as The Afro’s weekly cartoonist in the mid-1930s. Almost 50 years later, Bearden would create “Baltimore Uproar,” the iconic mosaic celebrating Billie Holiday and American Jazz at the Upton Metro Station on Pennsylvania Avenue.

Acclaimed journalists under Murphy’s tenure include the aforementioned Mitchell, who would become known as the “101st Senator” for his lobbying on behalf of the 1960s Civil Rights legislation; the courageous Civil Rights Era journalist Moses Newson (see "Editor Has a Close Brush With Death," below); William Worthy, who would defy U.S. Department of State travel restrictions and cover revolutions in China, Cuba, and Iran; J. Saunders Redding, an influential literary critic and the first Black faculty member of an Ivy League school (Brown University); and Baltimore-native Simeone Booker, who later became The Washington Post's first Black journalist.

Booker, in fact, had grown up around The Afro—Carl Murphy was a relative. He later explained in an interview with the Library of Congress that he had been inspired by his uncle to attend Harvard, winning a competitive Neiman scholarship, though it did not jumpstart his career the way he hoped. “When I finished, I wanted to go to The Washington Post, which I thought would be an advancement,” recalled Booker. “But when an opening came, I was so far down the ladder, I found my experience and Harvard background, unlike my Neiman colleagues, were of no use. I was a cub reporter.”

“I kept thinking about it,” he says. “I thought I could do something like it.”

The

historic exterior of The

Afro. —Courtesy of The Afro American Newspaper Archives

In 1951, Booker left The Washington Post for startup Jet magazine, where he served as Washington bureau chief, writing for it and its sister publication, Ebony, for more than 50 years.

Also hired under Murphys’ tenure: Howard grad and former semi-professional ballplayer Sam Lacy, who penned the must-read “A to Z” sports column for nearly 60 years. Lacy waged a decade-long campaign to integrate baseball as he chronicled the exploits of Negro League stars like Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell, as well as Hall of Fame Baltimore Elite Giants catcher Roy Campanella and Campanella’s future Brooklyn Dodgers teammate Jackie Robinson. Simply covering Robinson’s first spring training with the Dodgers proved stressful, Lacy later wrote.

“I felt a lump in my throat each time a ball was hit in his direction those first few days,” Lacy recalled in The Afro. “I was constantly in fear of his muffing an easy roller under the stress of things. And I uttered a silent prayer of thanks as, with eyes closed, I heard the solid whack of Robinson’s bat against the ball.”

Lacy distinguished himself as No. 42 did. He became the first Black sportswriter to join the Baseball Writers’ Association of America and earned entrance into the writers’ wing of the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Presciently, given its founding investor and women-led staff today, The Afro-American also became home for trailblazing women. In the 1930s, it was the first Black paper to hire female sportswriters when it brought Nell Dodson and Lillian Johnson on board. Predating Lacy, Dodson highlighted the disparity between Black and white ballplayers in pay and working conditions. She would be promoted to sports editor, writing a column called “Lady in the Press Box” in the late 1930s before covering arts and culture for New York outlets, including the Amsterdam News.

Brooklyn Dodgers

Roy Campanella, Jackie

Robinson, and Don Newcombe

at spring training. —Photography by I. Henry Phillips Sr., courtesy of Webster Phillips

Johnson, too, spread her wings and covered arts and culture, including a sit-down with Billie Holiday herself for a timeless Royal Theatre dressing room interview in 1937, gleaning some delightful details about the Baltimore background of the “New Swing Sensation” and Lady Day’s love of fashion.

“It’s a throwaway line here, but our history, our comprehensive history cannot be told through government records alone,” says Corey Lewis, one of two assistant archivists at the Maryland State Archives, which is holding The Afro-American archive until the Upton Mansion renovation is complete. “Without The Afro to fill in the blanks, to tell these stories, to show the humanity that you cannot find in government records, where would we be? Where would people who looked like the people in the communities that The Afro covered see themselves?”

Lewis continues during a walking tour through the long rows of the newspaper’s bound volumes at the temperature-controlled facility. “You might hear or learn about traumas during Jim Crow and segregation, but where would you read about the neighborhoods that were built? The businesses, theaters, and local shops? The camaraderie of those neighborhoods and places?

“The more I’ve come to learn about particular people, I’m astonished by their lives and what they did.”

Afro Charities executive

director Savannah

Wood hanging a banner

in front of the Upton

Mansion in 2023. —Photography by Schaun Champion

AS PART OF A Johns Hopkins University “Hard Histories” podcast hosted by prize-winning scholar Martha Jones, Wood talked about her journey of returning to her family roots to lead Afro Charities in 2019. A graduate of the University of Southern California and a working artist who had just turned 30, it was not a career she had planned. She was not born in Baltimore, but she did spend early summers here with her cousins, staying with her grandmother who, she said with a laugh, “would have us selling the newspaper out on the corner.”

Wood readily acknowledges she was not engaged with The Afro for most of her life. A seed was planted, however, while working with the Chicago-based sculptor and social installation artist Theaster Gates, who often incorporates historical materials into his projects. At the time, she was helping process a collection of racist memorabilia acquired from a Chicago couple. Afterward, moving back to Los Angeles, she became engaged with the archive of Octavia Butler through the arts nonprofit Clockshop, co-editing a catalogue and hosting a podcast related to the acclaimed science fiction writer and her work.

It was amid those efforts that she began reflecting on her own family’s story, asking herself, “I wonder what The Afro has.” She eventually visited Baltimore and the paper’s former home on North Charles Street where she saw in person for the first time the vastness of its archives. The wheels commenced turning about a full-time move to preserve and share that collection beyond the digitization of its bound newspapers, which was already underway.

An Afro-American

production worker

etching a printing plate.—Courtesy of The Afro American Newspaper Archives

Wood has since shepherded Afro Charities through an ambitious expansion, initiating new programming and attracting support from national funders, including the Mellon Foundation, the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, and The Ruth Foundation. She is also a visible presence in the city, receiving invitations from the Enoch Pratt, The Peale, and Baltimore Museum of Art, among other venues, to talk about her plans for the archives.

Although she spends most working hours handling administrative duties today, early on, Wood spent quite a bit of time in the archive itself. Several years ago, she found a box related to Martha Murphy and came to learn the details behind the $200 she had lent her husband to buy The Afro’s production machinery. Her father, also born into slavery, later became a successful farmer and it was discovered she had sold some of her inherited property to raise the funds. Before Wood knew it, she was on her way to Montgomery County to see the home where Murphy had lived after the Civil War.

For researchers from around the globe (not to mention this magazine from time to time) who request materials, the importance of The Afro as a leader of Black press is clear. However, it’s also hoped that by replanting the paper in West Baltimore and making its collection physically accessible to the community where it got its start, more people will be able to learn about their own family as well.

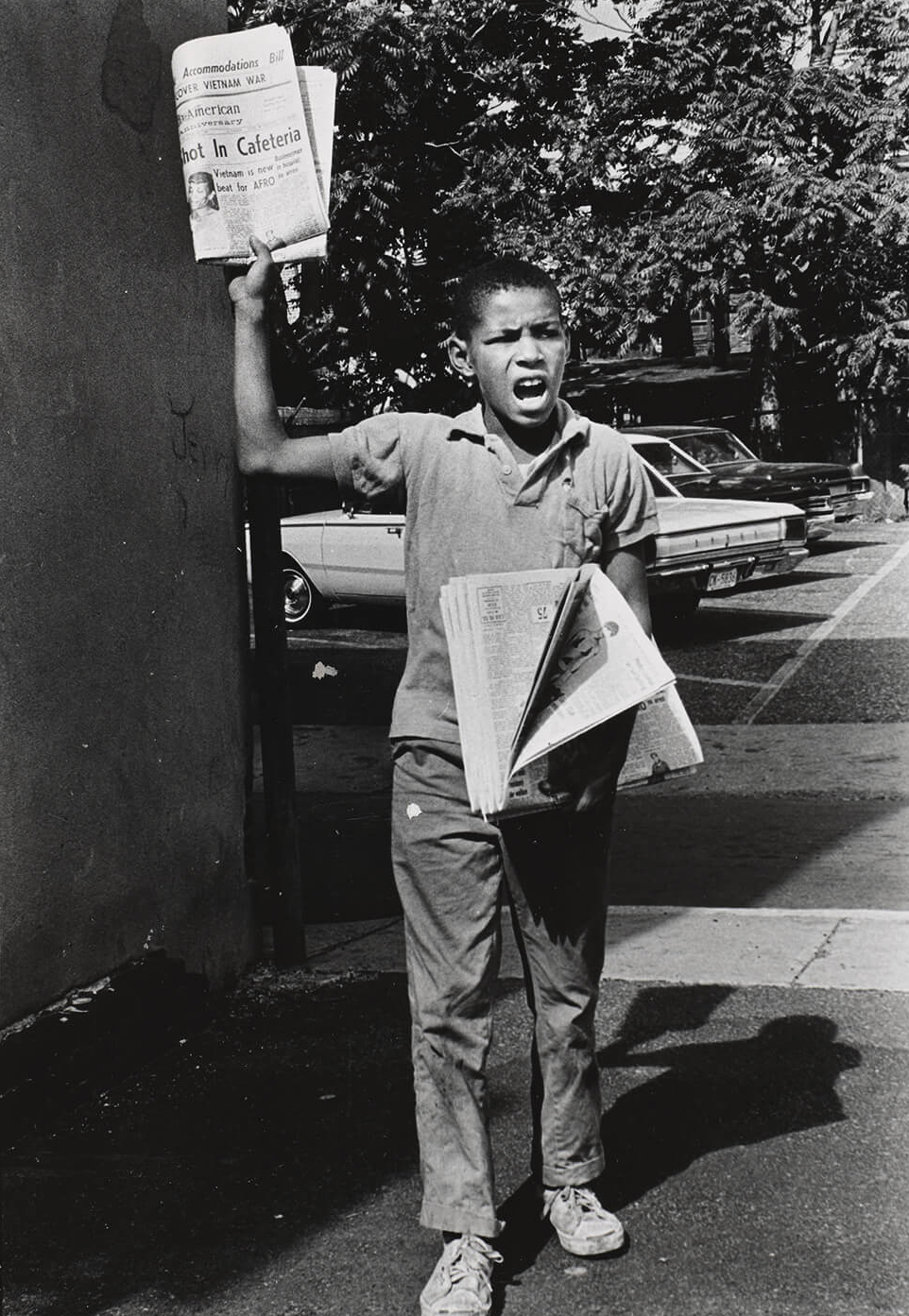

To that point, it is hard to overstate the bonds between The Afro and its local Baltimore community. Its paperboys back in the day included future Congressman Elijah Cummings, the first Black lawmaker to lie in state at the U.S. Capitol; former NAACP chief and House Representative Kweisi Mfume, who ascended to Cummings’ seat; and businessman Reginald F. Lewis, whose foundation was instrumental in the founding of the city’s renowned African- American museum that bears his name.

A Baltimore paperboy

selling copies of

'The Afro.' —Courtesy of The Afro American Newspaper Archives

In another genuine Smalltimore moment, journalist and documentary filmmaker Sean Yoes got his start at The Afro after meeting then-Afro staffer and future state Sen. Jill Carter at a Christmas party Mfume threw at The Walters Art Museum in the ’80s. “I was living in L.A., and I’d gotten back to Baltimore and was kind of searching for what to do next,” Yoes recalls. “We started talking and she said, ‘Well, what do you do?’ I said I was a writer, and she told me I should go down to The Afro and get her ‘old job’ because she was quitting.

She said, ‘Go to Bob Matthews,’ the editor-in-chief at the time, ‘and tell him he should give you my job.’ She was a talented writer, but she was leaving to focus on her law career.”

Everything good in the Black community The Afro covered, which alone made the paper invaluable, Yoes continues. “It advocated on behalf of Black people. That does not mean the stories weren’t accurate. It doesn’t mean they did not do hard news or that they weren’t, as some in the white community would have you believe, serious journalists. They were some of the most serious journalists in the U.S.”

Four of Carl Murphy’s five daughters, as Yoes highlights, earned journalism degrees from Big Ten schools and went to work for the paper. Their tuitions were paid by the state of Maryland as the University of Maryland would not admit Black students and then-Morgan College did not offer a journalism degree.

Once on staff, Yoes, who eventually become The Afro’s city editor, became enthralled with the paper’s “morgue.” He would go on to win an award for a story on former U.S. Senator and segregationist Strom Thurmond, documenting via The Afro’s archives that the former South Carolina politician’s mixed-race daughter—who made national headlines when she came forth in the early 2000s—had been an open secret in the Black press for decades.

Billie Holiday shopping

on Pennsylvania

Avenue; The Afro’s

famous “Clean Block”

program in action. —Photography by I. Henry Phillips Sr., courtesy of Webster Phillips

For Yoes, who still occasionally freelances for the paper, and many Baltimore families, life without The Afro is difficult to imagine.

“We had The Afro delivered to our house and, like a lot of Black households, we got The Sunpapers and the The News-American, too,” says longtime community activist and former Afro columnist Ralph Moore. “What was important about The Afro was that Black people weren’t featured in the other local media. When we got married, got promoted, died— none of that was covered by the white papers. The Afro’s presence, in terms of acknowledging our existence, was exceedingly important.”

Lisa Monroe, an educator and writer who worked on the staff of former Mayor Kurt Schmoke, says the same thing, describing The Afro as “a mirror for the Black community, where we saw our lives reflected in a true light.” The Afro’s unique dual role, she says—covering national and international stories of import, but also the stories of Baltimore— served as an antidote against the city’s all-too-often prejudiced white press.

“I grew up in the 1960s, in what would be considered a segregated community, but my elementary school was filled, thank God, with teachers who were very on top of social issues, social progress, and they always stressed to us how proud we should be that we had a paper like The Afro-American in our city,” says Monroe. “They were grateful the Murphy family held on to that paper long enough so that the revolutionary period of 1965, 1966, and our stories from that period, could be told by our own perspectives and these newspapers.”

She also reiterates that The Baltimore Sun rarely covered any kind of event in the Black community, “unless it was some kind of crime, and then it would be written from the perspective that this is what you expect from that community.” Never anything positive, she remembers, even when revered figures in the local Black community achieved a milestone. “At their deaths, they often wouldn’t be represented to any significant degree.”

In 2022, The Sun printed an apology for its racist legacy, which dates back almost two centuries and continued well into the 20th century. The paper supported slavery at its outset and ran advertisements for enslaved men and women. It acknowledged “through its news coverage and editorial opinions, The Sun sharpened, preserved, and furthered the structural racism that still subjugates Black Marylanders in our communities today.”

The 65-year-old Monroe has lived in Connecticut for the past 20 years. But her memory of The Afro, and the connective tissue it formed, remains so strong she emailed the live "Hard Histories" panel with Wood, Jones, and Brown University professor Kim Gallon, who is co-editing the forthcoming book, A Full Measure of Freedom: The Black Press at 200.

“The Afro was an institution like a church, like civic groups, like neighborhood associations,” Monroe wrote. “[And what] you heard at home or on the front porch, you heard a confirmation of in The Afro. The Afro was a printed record of what you learned through friends and family and essential in constructing and educating the Black community.”

Monroe still recalls that when she was young and out and about with her mother, folks in the neighborhood would talk about what The News American had said, and maybe reference reporting in The Sun if there was breaking news in the community. “Before they left each other, though, they would always say, ‘Yeah, but it’s going be in The Afro on Friday’—or if it happened over the weekend, on Tuesday—“‘so get The Afro because that’s where the story is really going to be told.’”

TIMELINE

A Brief History

FOR 134 YEARS, THE AFRO-AMERICAN HAS ADVOCATED FOR CIVIL RIGHTS, RACIAL EQUALITY, AND THE ECONOMIC ADVANCEMENT OF THE BLACK COMMUNITY, SERVING AS THE MOST WIDELY CIRCULATED BLACK NEWSPAPER ON THE EAST COAST FOR MORE THAN HALF A CENTURY.

—The Afro-American Newspaper/Gado/Getty Images

→

-

Future Afro publisher John Henry Murphy Sr. is born into slavery on Christmas Day in Baltimore.

-

During the Civil War, Murphy joins the U.S. Colored Troops, rising to first sergeant.

-

At 51 years old, Murphy begins publishing a Sunday school newspaper called the Sunday School Helper.

-

Borrowing $200 from his wife, Murphy buys the printing presses of the original Afro- American at a bankruptcy auction and merges it with the Sunday School Helper.

-

Murphy joins with Rev. George Bragg Jr., editor of The Ledger, to form The Afro-American Ledger.

-

The Afro- American urges readers to vote against the Poe Amendment, Maryland legislation meant to disenfranchise Black voters.

-

Carl J. Murphy assumes control of the newspaper after his father dies and remains its visionary leader for the next 45 years. At its peak, The Afro-American publishes twice-weekly editions in Baltimore and Washington, D.C., and weekly regional editions in 13 cities across the U.S., including Philadelphia, Richmond, and Newark.

-

Working closely with the NAACP, Carl Murphy and The Afro publicize the organization’s intention to challenge segregation at the University of Maryland.

-

Romare Bearden begins his career as Afro-American cartoonist.

-

Langston Hughes is hired to cover the Spanish Civil War and produces 22 stories.

-

During this period of segregation, The Afro- American publishes an annual travel guide, similar to the Green Book, listing hotels, restaurants, and other accommodations that welcome Black travelers in the eastern U.S., Cuba, Mexico, and the Caribbean Islands.

-

Reporter Moses Newson rides with Congress of Racial Equality Freedom Riders from Baltimore to New Orleans.

-

Carl Murphy and The Afro assist in the planning of Martin Luther King’s “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.”

-

Following the death of Carl Murphy, his daughter Frances L. Murphy II serves as chairman and publisher.

-

John Murphy III, Carl’s nephew, is appointed The Afro’s chairman.

-

John Jacob “Jake” Oliver, great-grandson of founder John Murphy Sr., is named The Afro’s new publisher and CEO, serving until 2018.

-

Frances “Toni” Murphy Draper becomes a fourth-generation descendant of founder John Murphy to serve as publisher.

-

The Afro offices and archives, including 3 million photographs, are slated to move to the historic Upton Mansion.

◆ Afro-American Newspaper / EST. 1891

Editor Has Close Brush With Death

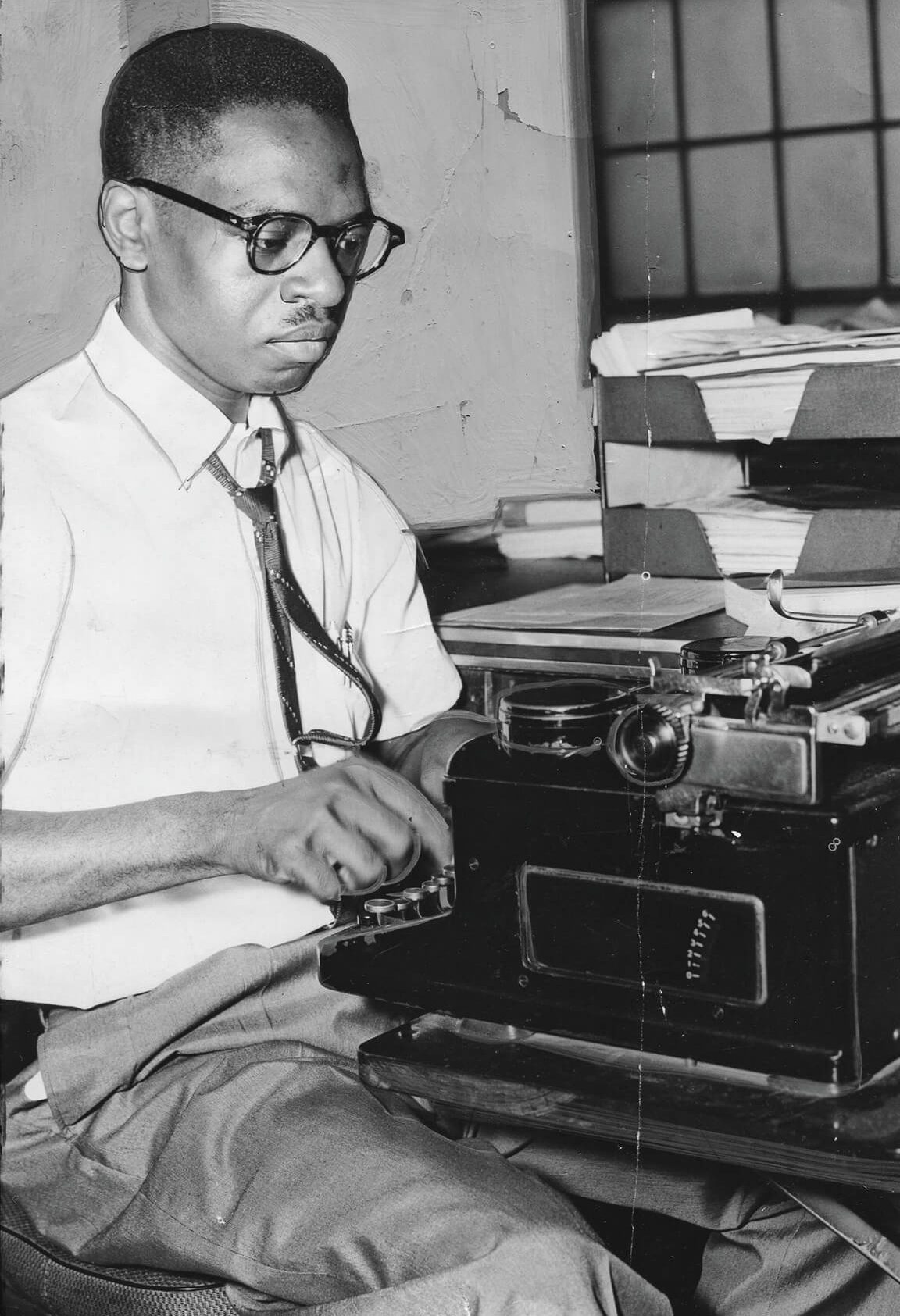

In 1957, Moses Newson—pictured below—left the Memphis-based Tri-State Defender and joined The Afro staff, covering the desegregation of Little Rock Central High School on his first assignment and later serving as the paper’s executive editor. Below is his first-hand account (lightly edited for length) of traveling through Alabama with the Freedom Riders, originally published May 27, 1961, and reprinted with permission.

By Moses J. Newson

AFRO City Editor

Baltimore, Md.— Friendship Airport never looked so good to me as it did Thursday afternoon when our jet pulled in from New Orleans.

After two weeks in the heat, hate, and hell of Dixie with the Freedom Riders, getting back to Baltimore brought back the feeling of being an American citizen with some rights under the law.

The colored citizen has no such rights in Dixie. Nor has the white man any rights, when he stands up for justice for his colored brother.

It may be hard for a person unfamiliar with Deep South tradition—as were some of CORE’s 1961 Freedom Riders—to believe or understand the difference in what the law says a citizen can do, and what a colored man can actually do in Dixie.

Southern state and local laws are rigged against the colored citizen and federal laws are simply disregarded.

Traveling with the Freedom Riders on their trip into the Deep South was a shocking and unforgettable experience.

There remains no doubt in my mind these uniformed guardians of the peace would have allowed the mobsters to come aboard the bus and beat us to a pulp had not state investigators, Eli M. Cowling and Harry Sims, kept them back.

There seemed to be a thousand cars behind us leaving Anniston and the little white one ahead stopping the bus. No police intervened.

Then the tire went flat and we stopped.

I have no idea what Cpl. Cowling or Cpl. Sims feel about integration. But they are men who believe in the law and in fulfilling their duty.

As long as I live, I will never forget the showdown look on Cpl. Cowling’s face after he brought his luggage aboard the bus and started strapping on his pistol while gazing out over the angry mob.

Alabama may not want to do it, but someone should pay tribute to these law officers.

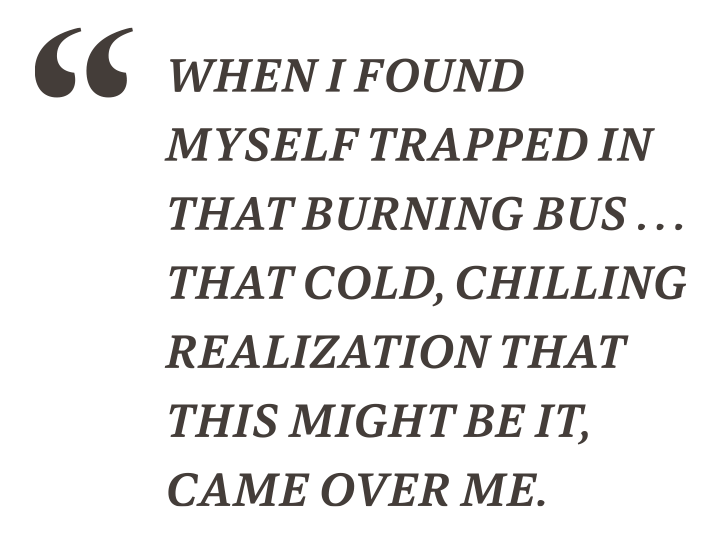

When I found myself trapped in that burning bus, set on fire by the mob, and the heat leaving me no choice but to go out the door and the smoke preventing my seeing where the mob stood, that cold, chilling realization that this might be it, came over me.

You make up your mind to take whatever is to be. I made one prayer, that my family would be all right, and one wish, that somehow, some miraculous way, I could step off that bus and have a machine gun in my hands.

Later, at Anniston Memorial Hospital, any doubts that law bows to racial hates and traditions were wiped from my mind.

“We’ll do the best we can in getting you to the city limits,” the Anniston officer kept saying, emphasizing the “best we can.” I remembered the best they did earlier in the day.

And there came the word of the Governor of the State of Alabama. The highway patrol was not available to offer us protection.

After all, you realize, you’re just colored folks and n——r-loving Yankees. No matter what United States law says, as one proud mobster explained, “This is Alabama and we’re gonna keep it white.”

The biggest letdown in the whole trip came at the Birmingham Airport. Try to imagine two full days of tension—and yes, fear for your life—and then the good, good feeling aboard a plane that will fly you away from the terrorizing human stalkers.

Deep down in your heart you’re happy. And like a nightmare comes the voice to say there has been a bomb threat and everyone must get off and return to the airport. It was pure torture.

On this dangerous trip through the Deep South with the courageous—every single one of them—Freedom Riders, there was opportunity to have a good look at colored and white.

The thing about the “new colored man” is true. They want every right accorded any American and they want it now—and they are ready to fight and die for it.

An example are the men who drove the 10 cars sent by the Rev. Fred L. Shuttlesworth from Birmingham to Anniston to rescue us. They knew the danger. They knew the need. So they came.

But the Deep South is not ready to accept gracefully the laws of the land. That was painfully clear in the “leering” faces and the policemen who looked the other way.

And again, even here in Baltimore, I am frightened.

THE DAILY HUSTLE:

The Photographs of I. Henry Phillips Sr.

For nearly two decades, Webster Phillips has been archiving his grandfather's groundbreaking work as a photographer for The Afro-American.

BY RON CASSIE

Photograph from

the BMI’s “Daily Hustle”

show. —Photography by I. Henry Phillips, courtesy of Webster Phillips

Through his lens, I. Henry Phillips Sr. documented the cultural royalty of midcentury Black America for The Afro. On assignment, he shot Coretta Scott and Martin Luther King Jr., jazz greats Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and Baltimore’s own Billie Holiday and Cab Calloway, as well as Ethiopian leader Haile Selassie on his first state visit to the U.S. Not to mention, Jackie Robinson at his first spring training, the funeral of John F. Kennedy, and several presidential inaugurations.

I. Henry

Phillips Sr. posing with one

of his favorite cameras.—Photography by I. Henry Phillips, courtesy of Webster Phillips

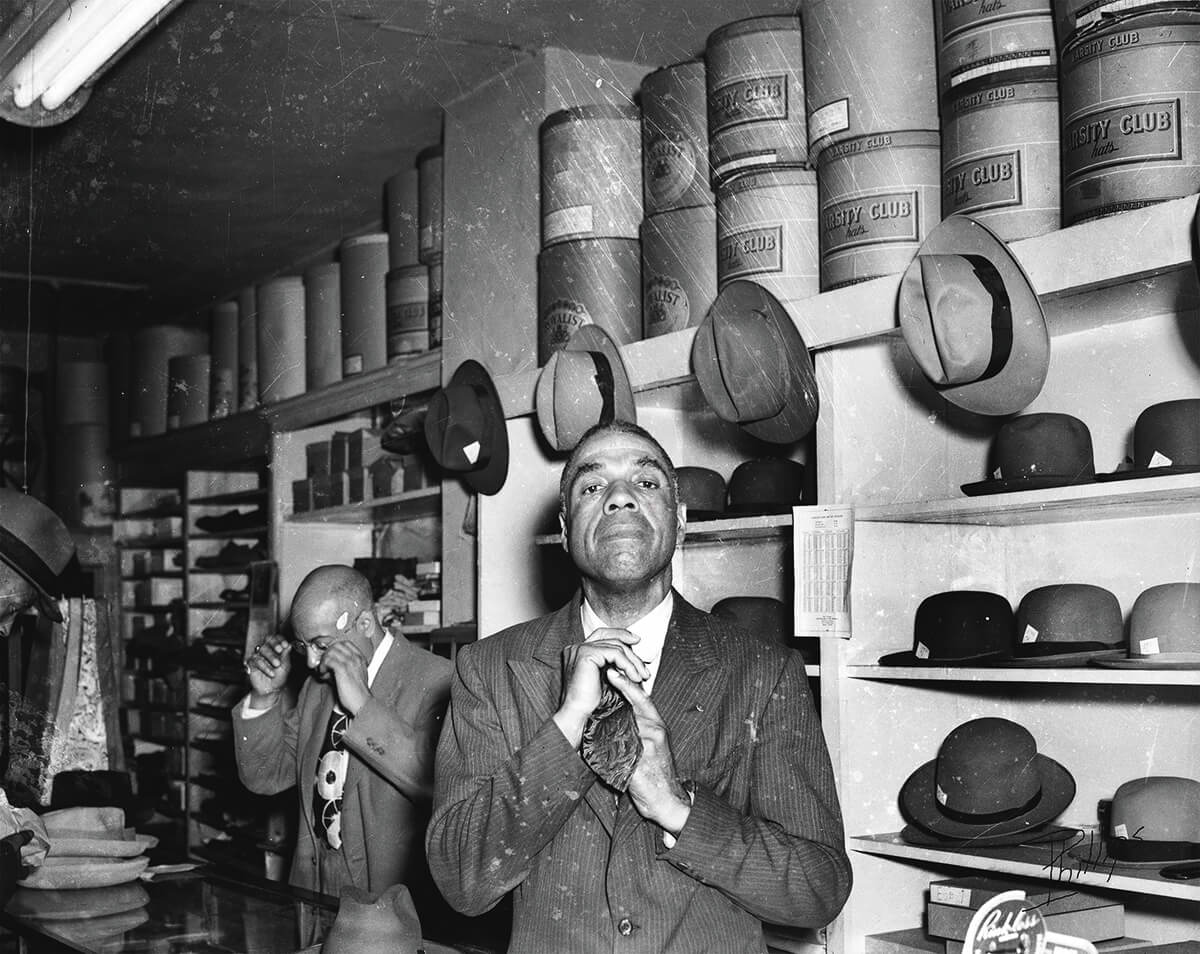

I. Henry Phillips Sr.’s contributions, however, run deeper and wider than shooting the heroes and stars of his day. He chronicled the joys—holiday celebrations, ballgames, graduations, weddings—and everyday life in the city’s segregated Black neighborhoods, events that were typically ignored by Baltimore’s white-owned newspapers.

On display through this month, the Baltimore Museum of Industry (BMI), in collaboration with grandson and archivist Webster Phillips, is presenting I. Henry Phillip Sr.’s work in an exhibition titled “The Daily Hustle”—a collection of photographs depicting the midcentury city’s Black workers and business owners while “emphasizing their grace, style, and community strength.” His photos document how entrepreneurship and labor built vibrant communities, portraying post-World War II Black communal spaces as symbols of resilience and hope.

The online archive that Webster Phillips has spent the better part of two decades organizing is important for researchers, academics, and journalists, but also for the local community. From time to time, an older Baltimore resident will see a photo that Phillips has printed for a show or posted on Facebook or Instagram (@ihenryphotoproject) and identify a beloved family member—in many cases, whose name had been lost. “One woman came to a show at The Parlor, a former North Avenue funeral home that is now a gallery, and she saw a photo of a little girl moving the tassel on a guy’s hat who had just graduated,” Phillips recalls. “She was the little girl from the photo. She said, ‘That’s me and my dad at his graduation.’”