History & Politics

Bugle Player

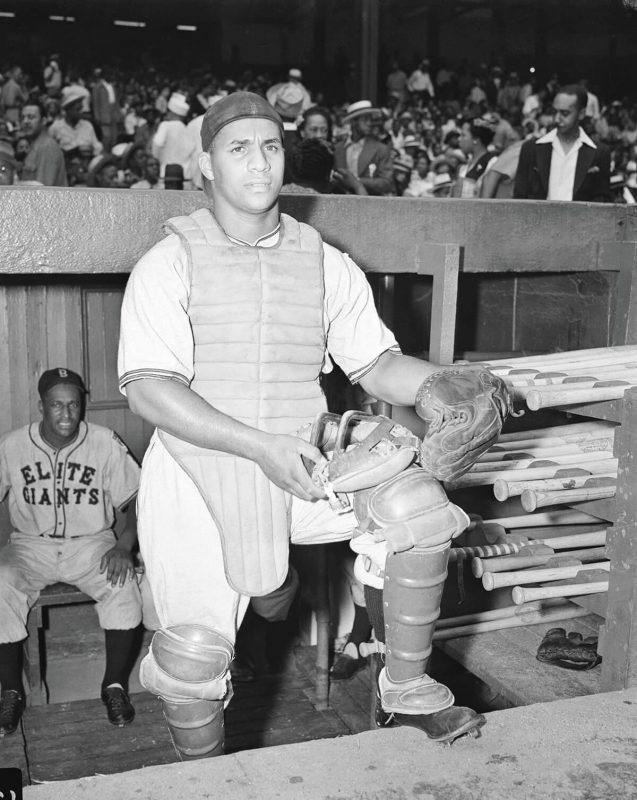

Former Baltimore Elite Giant Roy Campanella led the team to their first Negro National League title.

Othello Renfroe, a former Negro League all-star, once described catcher Roy Campanella as “the biggest 15-year-old boy I ever saw in my life.” According to Renfroe, when Baltimore Elite Giants shortstop Pee Wee Butts took infield practice, he’d get mad at Campanella, who began playing pro ball while in high school, for throwing the ball so hard to second base.

Just two years later, the stockily built prodigy, taking over the full-time catching duties at the end of the 1939 regular season, led the Baltimore Elite (pronounced ee-light) Giants to their first Negro National League title over the venerable Homestead Grays, including future Hall of Famers Josh Gibson and Buck Leonard. Campanella batted .353, smacked a home run, and drove in six runs in the five-game championship series. Nine long seasons later, he joined Jackie Robinson in the Brooklyn Dodgers’ infield.

At that point, Campanella began gunning down would-be base stealers with the assistance of another shortstop named Pee Wee—Reese. He would go on to win three MVP awards with Brooklyn’s iconic Boys of Summer, ’51, ’53, and ’55, the last being the same season he swatted two home runs and led Brooklyn to their first and only World Series title. This season marks the 50th anniversary of his own induction into Cooperstown.

Often forgotten, Campanella had been quickly joined by two other ex-Elite Giants on the Dodgers, pitcher Joe Black and third baseman “Junior” Gilliam, who earned back-to-back Rookie of the Year honors in 1952 and 1953. Not that all their teammates appreciated the influx of talent from Baltimore. Third baseman Billy Cox infamously asked baseball writer Roger Kahn, “How would you like a n—– to take your job?”

In fact, before signing with Brooklyn, Black and Gilliam had helped lift the Elite Giants to their second championship in 1949. It would prove to be the team’s last season in Baltimore, as white Major League owners had begun picking off the best young black ballplayers, sending Negro League baseball into a quick downward spiral. Cozy Bugle Field, where fans still in church clothes flocked for Sunday afternoon games and picnics, was sold and torn up just days after the end of the ’49 season. Today, the East Baltimore site stands vacant, without so much as a historical marker.

Also starring for the Elite Giants on the ’49 title team was legendary hurler Leon Day, who’d grown up in Mount Winans rooting for the then-Baltimore Black Sox. Day was already in his mid-30s when Campanella, Black, and Gilliam hit their stride with those memorable Brooklyn squads. He never played in white baseball but was nonetheless inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1995. “Oh my, Leon loved playing ball,” Day’s widow, Geraldine Day, recalls. “He was older when we met and didn’t tell me for two years he’d been a ballplayer. Then, he never stopped telling stories, especially about the barnstorming days. He never complained about any of it, not the bus rides or cow pastures they played in sometimes.”

Her husband, she adds, often faced Campanella when he pitched for the Newark Eagles, handling him well initially. “Leon always said he had no problem with Roy until he moved into white baseball. After that, on those barnstorming tours, couldn’t get him out.” Not that anyone else did, either, by then.

If you tabulate Campanella’s 162-game average, a full major-league season, it works out to 32 home runs and 114 RBIs over a career cut short twice—by racism at the front end, which delayed his start until he was 26, and a paralyzing car accident at back end, when he was 36. More than his heroics on the field, the accident transformed the wheelchair-bound Campanella into a universal symbol of courage.

“There was never any question about his ability,” Brooklyn scout Clyde Sukeforth said later. He’d recommended the catcher, maybe the greatest ever, to owner Branch Rickey. “Nobody discovered Campanella,” Sukeforth added. “We looked at him and there he was.”