Family

The Love Issue

We’re in the mood To talk about love.

“All you need is love, but a little chocolate now and then doesn’t hurt.” —Charles Schulz

It’s February, which means that love should be in the air. But lately, if you pick up the paper, watch the nightly news, or just step out onto the sidewalk, it certainly can seem in short supply. The mood has been mounting for some time now. Day after day, those once warm, fuzzy feelings have been replaced by emotions—fear, anger, toxicity—that don’t feel nearly as good. It almost seems as if we’ve forgotten how to cherish each other.

But love is a choice, and here at Baltimore, we choose love, one of two “cornerstones” that Freud famously said are critical to our “humanness.” (Work is the other, and that’s a topic also covered in this issue’s pages.) “Love is at the root of everything,” Mister Rogers once proclaimed. And we couldn’t agree more—so much so that we’ve decided to devote almost an entire issue to the subject.

MISTER ROGERS

Of course, we’re far from the first ones to be inspired by love—in ancient times, it was believed to be the epicenter of all emotions, thanks to the location of the human heart. It’s hard to read a book or a poem, listen to a song, view a great work of art, or even eat something delicious that wasn’t in some way influenced or inspired by love. From Shakespeare to Elizabeth Barrett Browning, look up “love” (and all of its derivatives) in Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations, and you’ll find more than 900 entries. (We enjoyed reading each and every one of them, some shared here!)

Love, says Towson-based therapist Michael Bombardier, is a unique emotion. “Most emotions arise in very specific contexts and mobilize to help us cope in certain situations,” he says. “Like fear, arising in the presence of a threat, but once that threat is done, the emotion naturally subsides. And yet, love has staying power. It functions to attach people like a mother and child, and it can exist along with a range of other emotions—you can be angry or disappointed with someone but still love them. You have all these other emotions that rise and fall, but love transcends.”

And while this powerful emotion prevails, that’s not to say it doesn’t hurt on occasion. On these pages, we take a hard look at love—not only the woefully inadequate, heart-shaped emoji icons that are used as a default response to every photo on Facebook, the saccharine-sweet expressions depicted on every Hallmark Valentine’s Day card, or the kind of love easily expressed with a box of chocolates and a dozen roses (though we celebrate that, too). We’re talking about something far deeper. We’re looking at love in all of its rawness, anguish, and aching beauty, the kind that can center you or make your heart race or bring you to your knees.

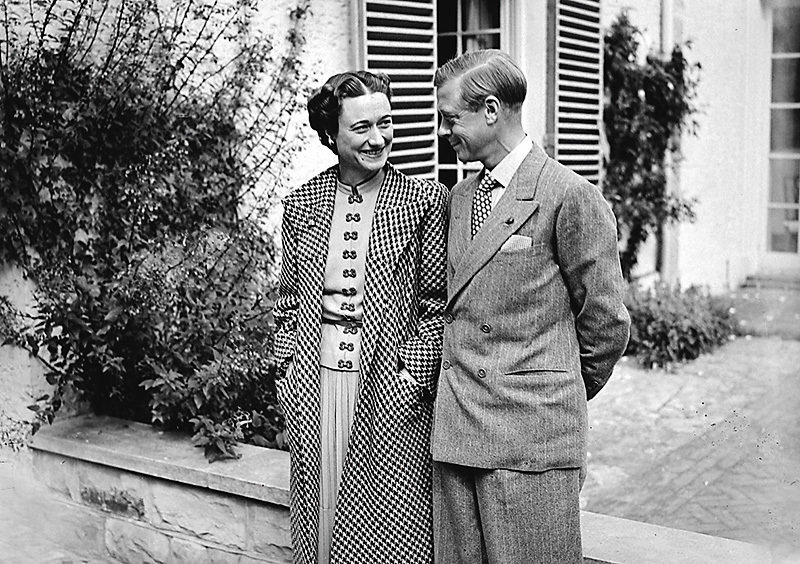

A LOVE PROJECT MURAL. WALLIS SIMPSON AND KING EDWARD VIII.

If you look for it in Baltimore, love is, quite literally, all around. It’s on our city streets—from Hampden to Highlandtown—where Baltimore artist Michael Owen and executive director Scott Burkholder gave birth to the Baltimore Love Project, painting 20 “Love” murals in the form of black silhouetted hands spelling out the word on the sides of buildings and schools. And it’s at Area 405 and Maryland Art Place, where Baltimore artist Peter Bruun recently launched his moving “One Thousand Love Letters” exhibition.

When it comes to romantic love, Baltimore can claim two of the world’s most famous stories of all time—one true, the other fictional. (And no, we’re not talking about Natty Boh and the Utz Girl, though that’s one for the ages, too.)

PROMOTIONAL POSTER featuring TARZAN AND JANE.

There’s the real-life story of British King Edward VIII, whose torrid love affair with then-married Baltimore native Wallis Simpson ended in his abdication of the throne (not to mention her divorce) in order to marry her. And then there’s the fictional story of beautiful Baltimore native Jane (née Jane Porter) from Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan books, who became Tarzan’s wife and was the daughter of, yes, a local college professor.

Beyond these examples, we’ve decided to find love stories of all shapes, stripes, and circumstances. We introduce you to Maryland’s first legally married same-sex partners, an 87-year-old married pair that met in second grade, and two matchmakers trying to help Baltimoreans “consciously couple.” We also highlight amorous body art and, in a series of essays, celebrate sibling, spousal, and parental love.

If there’s a universal theme to all of these stories, it’s this: Love is complicated, but it’s all we’re really after. Our hunger for it, in whatever form it takes, is the one thing we all share. “Love is the glue that brings us to other people,” says Bombardier. “It’s what draws us to each other and keeps us coming back. Love is the source of contentment and happiness, which is what most people say they want. As much as we can pursue other things—ambition, success, money—at the end of it, is the desire to be loved.”

“I have decided to stick with love. Hate is too great a burden to bear.”

—Martin Luther King Jr.

—Martin Luther King Jr.

Looking for Love

After losing his daughter to an overdose, artist Peter Bruun is buoyed by ink, watercolors, and love.

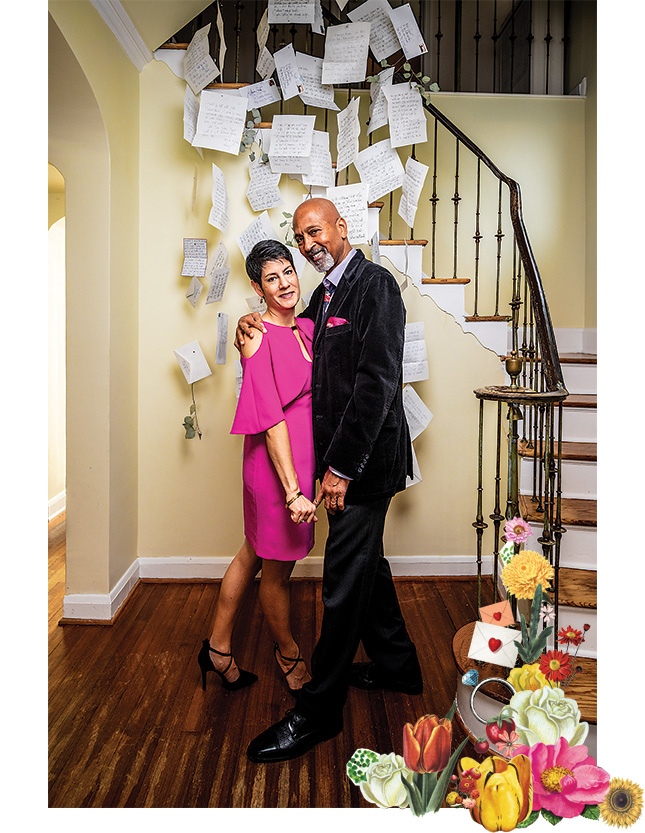

ALONZO & NICOLE LAMONT

Perfect Strangers

“There is only one happiness in this life, to love and be loved.” —George Sand

Alonzo and Nicole Lamont had already each found their “other” when they met at a bed and breakfast in Cape May, NJ, in 1994. Alonzo was visiting The Victorian Rose with his then-girlfriend of several years. Nicole was working as an innkeeper and was engaged to be married. But from the minute Alonzo first saw the 5-foot-2-inch brunette, he was immediately drawn to her. “She seemed like someone who tackled the world and won,” he concludes of his first impression, as he watched her tending to the duties of working at the seaside spot. At the time, Alonzo tried to make sense of why he was feeling so pulled toward a total stranger. “In life, you’re in different situations,” he says, “whether in a restaurant or a movie theater, and you see a person who looks attractive. I asked myself, ‘Was it just that, or was it a life-altering thing?’”

Over the next few days, as the playwright stole time away from his girlfriend to hang around the kitchen watching Nicole work—with Nicole somewhat unaware—he tried to find out. At the end of his stay, he recalls, “I shook her hand and her gaze lingered long enough for me to know that, yes, this was what I thought it was.” For her part, Nicole remembers that while saying goodbye to the handsome stranger, “I stopped breathing.”

Alonzo went home and wrote a love letter, which arrived within a day or so. It was handwritten across 10 pages on onionskin paper and began like this: “You must have known I was going to write to you.”

After reading the letter, Nicole broke up with her fiancé the next day and moved back home. Alonzo broke ties with his girlfriend, too, and within a month, Nicole was in Baltimore sharing a meal with him at The Helmand in Mt. Vernon. “We were sitting there and hanging out,” says Nicole, “when Alonzo said, ‘We are going to get married.’”

True to his words, within a year they were married at the Northwest Baltimore home where Alonzo was raised and they now live. When he’s not writing plays (or love letters), Alonzo works as a human resources specialist at the Johns Hopkins Welch Medical Library. Nicole is the studio manager at Ziger/Snead Architects. Together, they’ve shared tremendous highs and tremendous lows, including the loss of his 21-year-old son, Charles, whom they raised together.

But 25 years after meeting, their love is as alive—and electric—as it was the first time they touched each other’s hands. In fact, sitting on the sofa in their charming 1920s home, they’re still holding hands—and very much in love. “I feel honored in his eyes,” says Nicole. “He honors me every day in so many ways. I travel very confidently in this world, because I have a safe spot to land every single time—every time.”

As for Alonzo, a self-professed one-time Casanova, settling down is not something he ever saw for himself. And yet he has, quite happily. “At her heart,” says Alonzo, “Nicole is a beacon of truthfulness and real genuineness, and it cuts through everything. Part of marriage has been realizing that I’m not the sun and I can orbit around someone else.”

That first letter—and others like it—are now stowed away in a red Whitman’s chocolate tin under a bedroom bureau upstairs and taken out for an annual reading on their November 5 anniversary. (Some also float down from the stairwell.) As Nicole sits on the sofa, she’s still mystified that they met and married. “Who gets this?” she asks as she gazes adoringly at Alonzo. “Who gets this?”

CARYN ANTHONY

Love, Always

“The art of love is largely the art of persistence.” —Albert Ellis

Almost to the date, Caryn Anthony can cite—chapter and verse—each of her son Robby’s hospitalizations, which first began at the age of 16, when a blood clot appeared in his leg while he was on a community service trip in Colorado. She remembers the symptoms that led to his admission, the length of his stay, the names and dosages of the many medications and immuno-suppressants he took to manage the disease and later, when things got really bad, to keep him alive. There’s very little she doesn’t remember.

And although the details of his illness, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, a rare blood-clotting disorder that took his life at age 20 on July 19, 2016, have been seared into her memory, so, too, are the happier times—and she relishes them.

As she sits on the sofa in the photo-filled family room of the Silver Spring home she shares with her husband, Brad, Anthony smiles at the thought of watching Eagles games and The Walking Dead with Robby, seeing him get his black belt in karate, and watching him graduate from high school, at which point he towered over her by a whole foot.

“You keep someone alive by talking about them,” says Anthony, who often pauses in the conversation to show photographs of her beautiful blue-eyed boy: Robby sitting on his bed in his freshman dorm room at Temple University; the handsome boy being taken on a gurney, giving the thumbs up after he’s loaded into an ambulance; an ebullient teenager in the seat of a red Corvette—a bucket list item realized.

One thing that you notice is that when she speaks about being Robby’s mom, it’s always in the present.

“In the world of who I am,” says Anthony, “I have two children. It doesn’t matter that one of them isn’t here. My daughter is not an only child. And a lot of the things that I love about being Robby’s mom are still here.”

Robby’s passing, she says, has taught her invaluable lessons about love.

“I learned that love doesn’t end,” says Anthony. “It’s still there—there’s not this finite amount that you use up under difficult circumstances. For me, it was a stream that didn’t end—it was always going to be replenished.”

“When Robby got sick, Anthony left her job working at a Maryland nonprofit. “A wrecking ball moved through my life,” is how she puts it, and after her son’s death, she had to figure out a new path forward—and a place to put her love.

“Now back at work, Anthony volunteers at D.C.’s Children’s National, where Robby received the majority of his treatment. She helps medical teams make improvements to their practices and procedures.

To help process her pain, she also started writing, including a blog post dedicated to her son that began: “Even though you’re gone, in a strange and surprising way, I find that I’m not done being your mother. I thought that losing you would stop our relationship. I would have memories and mementos to hold dear, but that would be all. Instead, I find I’m actually building a new relationship with you now.”

What Anthony has come to understand is that you can’t have the love without the loss. “A long time ago, I read a poem [by Kahlil Gibran] that said something like, ‘Sorrow digs the cup that holds the joy,’” she says. “You don’t get the one without the other—and it’s unreasonable to expect it to be any other way.”

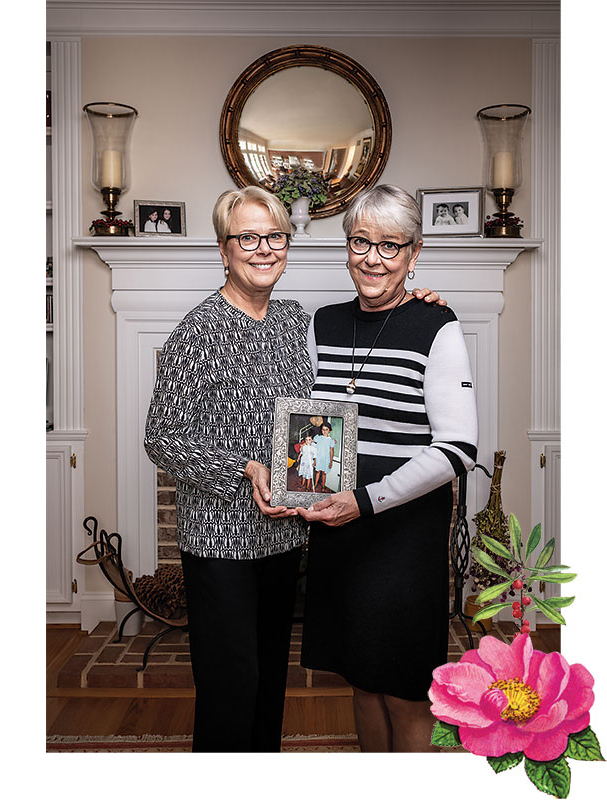

Ileana & Ioana Gheorghiu

We Are Family

“Love is the greatest refreshment in life.” —Pablo Picasso

For all of their 63 years, twin sisters Ileana and Ioana Gheorghiu have shared just about everything. Growing up in a small city in Romania, from preschool through medical school, the best friends were never apart. “Our parents never separated us,” says Ioana, who was born first and a whole pound heavier than Ileana. “So the bond was very, very strong.”

To this day, the only time they’ve ever been apart was when Ileana came to America in 1985 to receive treatment for breast cancer, though Ioana followed five years later. Through the years, the sisters, who now share a sprawling home in Stevenson, established successful medical practices—Ioana as a pediatrician at Sinai Hospital; Ileana as an anesthesiologist at the University of Maryland Medical Center.

Though Ileana has let her hair grow gray and Ioana is a blonde, Ileana wears glasses that are more round to Ioana’s square style, and Ileana is slightly taller than Ioana, there are few differences between them. Even so, it’s only been a few years since they learned they were identical when Ileana, who suffers from multiple myeloma, needed stem cells and doctors discovered through bloodwork that Ioana was a perfect match.

As young girls, Ioana and Ileana both hoped to marry and have children. “Our parents were 34 and 35 when they had us,” says Ileana, “and I thought they were too old. I was going to marry young and have children.” But when that didn’t happen, they turned to the idea of adopting children together. “I was talking so much about it that my sister said, ‘Either do something about it or stop talking about it,’” recalls Ileana, wiping away tears as Ioana does the same.

So in 2000, for many reasons, they made the decision to adopt two sisters, Stefania, then 5, and Valentina, then 3, from an orphanage in Romania.

“Neither of us expected not to be married and not to have a biological family of our own,” says Ileana. “But when life turns a certain way, if you want to do something, then you pursue it, and we accomplished having a family in a different way.”

And while raising children together away from home and without the support of extended family hasn’t always been easy, it has only strengthened the bond between Ioana (known as “mommy” to their girls) and Ileana (known as “mama”).

As they’ve raised their daughters together, a sense of humor has been key. “I’ve always told my girls that no matter how much we fight, it’s not like the usual husband and wife,” says Ileana. “We will never get divorced—that’s one good thing about being sisters.” The girls, now 24 and 22, are leading lives of their own. Stefania is pursuing a master’s degree at University of Maryland, College Park; Valentina is a senior at Dickinson College. Both bear the middle names of their moms. Says Ileana, “Because I’m a little OCD, it was my idea to give them our first names as middle names and to make their names have exactly the same number of letters in them, which meant that Valentina took Ioana’s name as her middle name and Stefania took my middle name—they both will always have a little part of us.”

Henry & Joan Marconi

School Days

“The opposite of love isn’t hate; It’s indifference.” —Elie Wiesel

While most of Henry Marconi’s memories of meeting Joan for the first time at Blessed Sacrament School faded away decades ago, he has his theories. “I probably failed a spelling bee, and she probably won it,” he says, laughing. And while Joan confirms that Henry’s memory is likely accurate on that count, it wasn’t exactly love at first sight—though in fairness, it was only second grade.

As they grew older, “I dated older boys, because at 5’2”, I was the tallest person in my fifth-grade class,” says Joan, a petite blonde. “And I haven’t grown since.” Chimes in Henry, “And I was probably about 4’11”. I didn’t grow until I was with the Air Force.”

Sitting at their dining room table in the Loch Hill home where they raised six girls and a boy, Joan looks at the yellowing black-and-white photos of days gone by. There’s the prom photo taken in the high school’s gym when she was 18 to his 17, the wedding photo in which Henry admits he was “nervous,” and the one photo of just Joan that Henry kept taped to his tent when he served for 19 months as a weapons expert in Morocco for the Air Force.

Of course, it didn’t hurt that in addition to writing him letters, Joan sent him homemade cookies packed in beautifully wrapped tins. “When they got to me, they were still fresh,” recalls Henry, smiling at the memory. To pass the time in the desert, Henry gambled with his compatriots, winning $900 in a craps game one night. He decided to save most of the money so he could buy Joan a ring. Back in America, on December 28, 1953, they were married.

Along the way, Henry trained to be a tailor. “It was Al Jolson’s cousin who taught me to sew, and he was one hell of a tailor,” enthuses Henry, who still sews Joan’s hems on his 1968 Singer sewing machine in the basement. For her part, Joan ran the hectic household. “We were under a lot of pressure raising those children,” says Henry. “Just getting it done and leading a decent life while we were doing it was hard. I had to make it work—and believe me it wasn’t always so easy. There were times when I wanted to run away. Joan had to make it work a different way.”

Still, he has stayed for 65-plus years—around this very dining room table that’s now stacked with memories, and where stews, spaghetti, and fried chicken were once served to their hungry brood, who are now feeding their own children. “I had dinner for all these people,” recalls Joan. “It’s a tough job feeding nine people every night.” When asked what means the most to them in a room filled with photographs, oil paintings, and bric-a-brac, Joan doesn’t hesitate. “I’m happy to have Henry,” she says smiling at him. Says Henry, without missing a beat, “And I’m happy to have you, Joan.”

Sharon & Katie Dongarra

Happily Ever After

“There is always some madness in love. But there is also always some reason in madness.” —Friedrich Nietzsche

It was love at first sight when Katie Cleary, left, who had just gotten a job at the fast-food drive-through window at Arby’s in Seaford, DE, saw Sharon Dongarra working the meat slicer. Though Sharon was older, they were both teens at the time. Sharon recalls the moment like it was yesterday. “I was on the back of the line at this meat slicer. After I was finishing making a sandwich, I remember going to wash my hands. And I remember looking up, and there was Katie Cleary with her big brown eyes and a big smile. I thought at the time, ‘That’s an interesting smile.’”

As Katie sits by Sharon’s side on a wicker love seat on the deck of their Loch Raven Hill home, she smiles adoringly at her wife. “It was love at first sight,” confirms Katie, now a hedging coordinator at a local mortgage company. “But I don’t think I realized that’s what was happening—I was just madly attracted to Sharon.” Twenty-three years from the time they shared their first kiss, the pair, whose front door features a “Home Sweet Home” sign, has built a life together—and a family, including a daughter, Lucy, 8, and a son, Archer, 4.

Early on, the duo wasn’t interested in putting a legal label on things, and when domestic partnership in Maryland afforded some protection in 2003, they bristled at the idea, wanting to wait until gay marriage itself was legal. “It can be infuriating when you want to have something that other people have that’s recognized in a way that you aren’t,” says Katie. But as they watched their straight friends marry, they had a change of heart. “Friends were having these beautiful ceremonies and celebrating their love,” says Sharon. “And we were always the bridesmaids,” Katie chimes in.

As Sharon headed off to school in Georgia and Katie uprooted her life to go along, it was Sharon who decided they should have a commitment ceremony. “We were about to give up our jobs and leave our families, and I thought, ‘We are cutting our nose off to spite our face,’” says Sharon, now a chiropractor.

So, in 2006, with Sharon wearing a pantsuit her mom made and Katie wearing “a creamy thing from Nordstrom,” they had a civil ceremony—“a whole big thing with 80 people,” says Sharon—at the American Visionary Art Museum. Along with their vows, they exchanged white gold wedding bands inscribed with the word: “unconditionally.”

In November of 2012, the approval of the Civil Marriage Protection Act in Maryland changed everything—and nothing. Though it didn’t change their love for one another, the duo—who by then had become parents to Lucy, whom Katie carried, along with Archer, who was born in 2014—decided to formally legalize their love in the eyes of the state.

“It brings a level of anxiety when you are operating outside the law,” says Sharon, “especially if you have a child in common, with whom I had no biological connection. We were like, ‘Let’s just do it the right way.’” So on January 1, 2013, one minute past midnight, when the law officially came into effect, with a few neighbors and Sharon’s terminally ill mother in attendance, they were joined in holy matrimony as wife and wife—and were likely the first legally married same-sex couple in the state. Sharon’s brother and sister-in-law helped stage the space for the party. Sharon’s mother, a tireless proponent of gay rights, joined the celebration just before midnight. “Casting her vote for gay marriage a few months earlier was one of her final acts,” says Sharon, “so it was particularly meaningful.”

MATCHMAKERS Q&A

All You Need Is Love

Two local women help Baltimoreans make the perfect match.

“Years of love have been forgot in the hatred of a minute.” —Edgar Allan Poe

On the heels of her separation in 2007, Tammy Tilson started the work of rebuilding her love life. “I had never dated much in high school,” says the Baltimore native, “so I was having fun, living my 20s in my 40s. I had an online dating profile, and I was really into it.” In her professional life as a therapist, Tilson, who specializes in relationship counseling, had spent many hours listening to her clients discuss dating and intimacy issues. “I found myself gravitating toward the subject,” she says. “I was always thinking of business ideas, and I thought, ‘Maybe I’ll become a dating coach.’” Fast-forward 11 years, and the therapist, along with her business partner Kimberly Simonetti, who creates client profile portraits, has made many a successful match. And Tilson, who recently remarried, is living happily ever after herself. Recently, we sat down with both Tilson and Simonetti to talk about the art of matchmaking.

What makes someone a good candidate for your services? “You have to want a committed, loving relationship,” says Simonetti. “You have to be ready for that next step and be drama- free—if you’ve been married, you have to have been through with your divorce.”

What type of intake do you do when you meet clients? “We spend an hour or two asking lots of questions, their type, but also their relationship history, why past relationships didn’t work out, what they are looking for in a relationship, and why they haven’t found it yet,” says Tilson. “If they decide they want to go forward, we do a criminal background check and have our own software with their extensive profiles—it’s the opposite of swipe right.”

Tammy, how has being a therapist helped you with this work? “I understand that people want to feel loved and accepted and connected. For people who don’t have it, they feel like they’re not a part of this world. It leaves some feeling like, ‘What’s wrong with me?’ There’s a lot of overlap with my therapy work.”

What are some of your matching challenges? “It’s a challenge getting people to be realistic,” says Tilson. “It’s not about settling, but it is about being realistic.”

What advice do you give clients? “You never know how you’re going to feel until you are face-to-face—and that might not happen on the first date,” says Tilson. “Feelings can develop. You don’t have to have sparks. Just ask yourself, ‘Do I like this person enough to have one more date?’ You don’t have to figure out, ‘Is this the person I’m going to marry?’”

Where do you find your matches? “We take about 30 clients at a time but also keep a database of people who might not be able to afford our services but want to be in the inventory,” says Tilson. “I swear to God, I go to the dry cleaners and if I see the guy next to me doesn’t have a ring, I give him my card—I’m looking all the time.” Adds Simonetti, “I went to Maryland Live! for the cattle call for The Bachelor. Obviously the people there are interested in a relationship, because that’s part of the show, but not everyone is going to make it on, so it’s a good place for us to meet people. When the producer found out, he tried to kick me out.”

Kimberly, why is the portrait important? “I know it sounds shallow, but if you don’t have a captivating picture, no one cares what you have to say.”

What has matchmaking taught you about love? “It makes me appreciate more of what I have,” says Tilson. “It’s about how someone treats you and how you feel when you are with them. If you find a good person who is honest and who cares about you, I don’t mean to sound corny, but that’s what life is all about.”

MAX & FELICIA Weiss

Soul Sisters

They say friends are the family you choose.When it comes to my best friend and sister, she’s both.

“Love is composed of a single soul inhabiting two bodies.” -Aristotle

It’s a known fact that all siblings fight, and my sister, Felicia, and I are no exception. When we were tweens and we’d have one of those fights—the slammed-doors, silent-treatment, furiously scribble-our-grievances-into-our-diaries type of fight—it was generally resolved like this: One of us would skulk into the other’s room and sheepishly mutter under her breath, “Wanna play duets?”

Felicia plays piano and I play cello. We started playing when we were very young—not quite Suzuki Method young, but young all the same—and it’s always been the way we connect. Through music, we expressed things we couldn’t express otherwise, bonded over a shared passion, and created something, together. By the time the practice session was over, we had forgotten what the fight was about. That was secretly the point.

In the Weiss household, family always came first. This value was instilled from a very early age by our parents, and it was rarely challenged. Friends come and go, we were reminded: Family is forever.

To this day, the moment in my life that brings me the most shame—the kind of memory that can actually rock me awake at night—involves my violation of the Weiss code. The whole family had packed up and moved from New York to Florida (a failed experiment that lasted all of a year), and we settled across the street from two cute brothers—tanned and floppy haired and preteen dreamy—about the same age as Felicia and me. One day, we took our bikes out for a ride, the two brothers pedaling ahead and exhorting us to catch up. In the rush, Felicia fell off her bicycle. “Hurry, hurry!” the boys yelled at me. I took an anxious glance at Felicia and pedaled on to catch up with the boys.

I know.

Felicia was fine, by the way. A few scrapes and nothing more. But I would never be the same. No amount of yelling from Mom and Dad could match my shame and self-loathing. I resolved to never betray my sister like that again—over a stupid boy, no less—and I never did. Fast-forward a few decades and Felicia and I are as close as two sisters can be. She’s two years older—or “22 months” as she is always quick to correct—an age difference that meant something when we were kids but is negligible now.

Through a quirk of fate, neither of us is married or has kids (light a candle for our long-suffering Jewish mother), and we jokingly refer to each other as our “significant other.” We travel together—recent trips have included Spain, Italy, Paris, and Austin, Texas—we shop together, we binge-watch TV together, we walk our impossibly spoiled dogs together, we explore new restaurants (always mapping out a perfect entrée-sharing plan), and we go to museums and concerts. Music is still a major shared passion. We play a lot of chamber music, often with our friend the violinist Renée Roberts, who fancies herself the “third Weiss sister.” (She’s not the first of our friends to call herself that—it’s kind of a coveted role.)

Mostly, though, we laugh together. Felicia and I are different in lots of ways. She’s more reserved, less explicitly extroverted, but we have the exact same sense of humor. Every time we get together, there’s at least one moment when we start laughing, and the laughter becomes contagious, giddy, run amok, and we’re both doubled over, and one holds up a finger as if to say, “If you crack one more joke, I’m literally going to pee my pants,” which is basically a perfect challenge to keep the joke going. I don’t laugh with anyone else like that.

Felicia and I still fight, of course, but they are few and far between—and quickly resolved, even without the benefit of duets (although they do still come in handy from time to time). We simply mean too much to each other to ever stay angry.

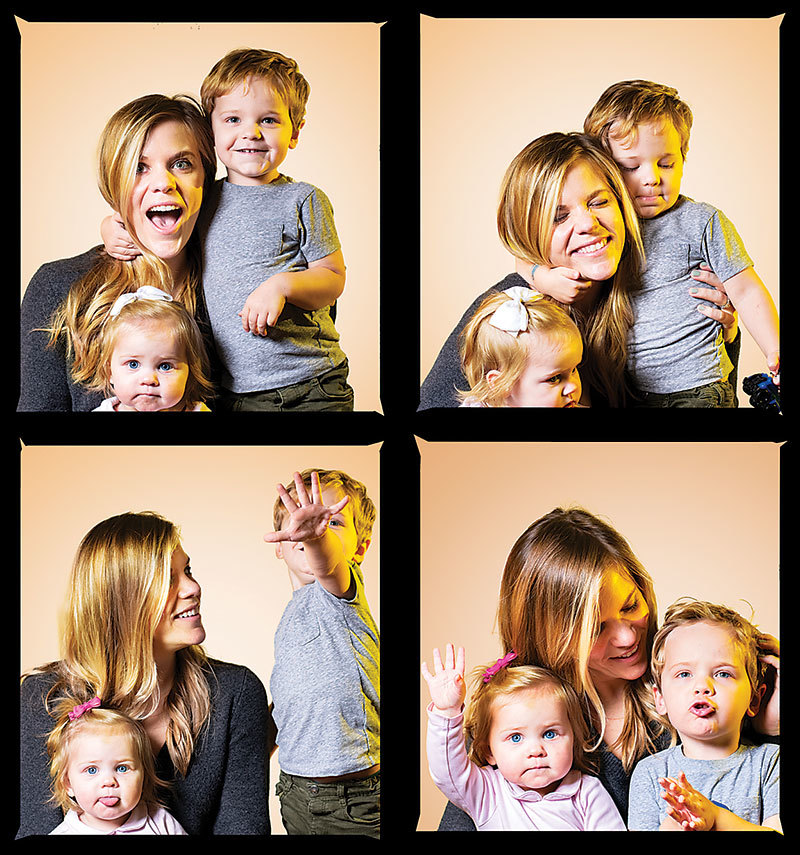

MEGAN, EDIE & LOU Isennock

Kids Are Us

Parenting can be hell—and heaven.

“Doubt thou the stars are fire; Doubt that the sun doth move; Doubt truth to be a liar;

But never doubt I love.” —William Shakespeare

But never doubt I love.” —William Shakespeare

I have a parenting mantra. I am not a mantra-type person. I prefer to be keyed up and anxious. But having kids changes your brain and makes you do weird, off-brand things. My mantra grew quietly from a song I liked to something I repeat many times throughout the day. It will surprise no one who knows me to learn it’s borrowed from my unrequited childhood crush: the glittering, talented Sir Elton John.

Don’t wish it away, don’t look at it like it’s forever. This lyric—excuse me, mantra—applies across the entire spectrum of my motherhood experience. When my children are being magical and ask me in their tiny voices to lie in bed with them while they fall asleep, my mantra is there, like a drumbeat, reminding me that their roundness and newness is fleeting and that my presence and participation is required. It’s there in the bad times, too, like at 2 a.m. when Edie is on her 45th minute of screaming. I lie perfectly still and my mind ping-pongs between guilt and frustration with my extremely extroverted daughter who just wants to hang out. But her piercing screams push through my cracks. And in these low moments in the middle of each night, my mantra pops up and reminds me that this is just a season. I’m not actively wishing this time away, but knowing that it’s not forever, as Sir Elton sings, adds perspective. Parenting so far has been a balance of these feelings—inelegantly plodding through the tough, early years while pleading wild-eyed with time to please slow down. And I could not have understood how these emotions could run concurrently until our kids were born. Ever since their arrivals, we’ve been sleep-deprived and, as a result, my memory and skin elasticity are suffering.

Moments of unadulterated joy can be brought down in a second by the insanity of toddlerhood. Our son, Lou, once slapped me, in public, because he thought I left the cake we bought for his stuffed penguin’s fictitious third birthday at the bakery. Our daughter, so eager to be in the mix with everyone else, started walking at 9 months. I’ve had to document the bruises she has sustained from walking too early in case our parenting is ever called into question. The past three years have been grueling, complicated, and expensive. But.

I grew their hearts in my body. They came into the world and we were totally consumed by every breath and sigh and smile. We marvel daily over our son’s curly hair and bastardization of the word “applesauce.” We yell “HI EDIE” to each other because that’s how she greets everyone. I’ve exploded with pride watching my boyfriend become my husband become the father to my babies. I’ve seen myself change from a well-rested millennial to a selfless wonder woman who does things like have C-sections and give her son the cheesiest slice of pizza in the box. My love buoys me—a heart-shaped life preserver in the sticky (why is everything always so sticky?), tumultuous, beautiful ocean of parenthood. This time in our lives won’t last forever, but man, do I wish it could.

Janelle & Ron Diamond

I’ve Got You, Babe

Sometimes we have to look back to know where we’ve been.

“Love sought is good, but given unsought better.” —William Shakespeare

I often think back to 2011 as the litmus test to my marriage. We had bedbugs, newborn twin boys, and a cancer diagnosis that would take my mother-in-law’s life before the year was up. It was one of those “If we can survive this, we can survive anything” trials. And we did. That year had the highest of highs and the lowest of lows—and we came out less, but still whole, beaten down, but still standing.

I think about relationships a lot in my job. As managing editor of Baltimore Weddings, I chronicle couples all aglow with newlywed radiance, high on love and possibility. I never feel bitter—a 40-something married lady with tales of woe as they breathlessly recount the proposal and wedding planning. Instead, I relish it. It always takes me back to when Ronnie and I first met almost 18 years ago, two weeks after 9/11.

We were set up on a blind date (yes, those existed pre-social media), and on our very first date, I knew that I would marry him. He made me laugh more than anyone else. (He still does.) He cooked me eggplant Parmesan on our second date, and we ate it on the futon in his studio apartment. (The futon that was always mysteriously in bed mode, never couch mode.) A month later, he met my parents.

I often think back to those early days when the happiness seemed to emanate from every cell of my body. It was a time when love meant him driving me back to my apartment in D.C. instead of depositing me at the Metro. I can picture us at the bar, tipsy, as we talked about moving in together—and then did, first into my studio apartment (another “If we can survive this, we can survive anything” moment), before upgrading to a palatial one-bedroom, and finally a rowhouse in Baltimore.

There were so many other firsts: the first time he met my friends. The first party we hosted together. Bringing him home to meet my parents. Discovering at our first Thanksgiving together that we were born at the same hospital in New York state, where neither of us had lived for very long. When he proposed at Boulder Falls in Colorado.

Telling him I was pregnant for the first time. Telling him I was pregnant for the second time. And the look on his face when we realized that the third time, I was carrying twins.

I’ve come to realize that life is never how you think it’s going to be. I never (ever) thought that we would have four children. Or financial stress. Or doubt. Or screaming fights. But I also didn’t count on the overwhelming joy of holding a baby that represents the best of both of us. How lying on a couch and watching TV, our kids asleep upstairs, could be just as satisfying as our dating life used to be. But working at a wedding magazine reminds me that our marriage is no different than all the others— we’re just farther down the road. Eggplant-Parmesan-on-a-futon foreplay is now a distant memory, but when he walks in the door with Trader Joe’s grocery bags, my heart still flutters.

Jane & Mike Marion

’Til Death Don’t Us Part

My husband proposed all over again.

“Love doesn’t die, people do.” —Merrit Malloy

Do you think we’ll ever get divorced?” Just a few months ago, over a quiet dinner, Mike asked me that question. It took me by surprise and made me wonder why he was asking. My mind went back to thoughts of how our betrothal began.

We had been dating for six years. I was in graduate school in New York City, and he was visiting for the weekend, a ring safety-pinned to the inside of his underwear as he nervously negotiated several forms of public transportation. It was the night before Halloween and he handed me a small, white box. “Trick or treat,” he intoned. “Treat,” I responded. And as I opened the box, in which his “bloody” finger wriggled up through a hole in the bottom, I screamed, “I said, ‘Treat!’” “Look again,” he said, and there, tucked inside the bloody cotton, was a magnificent pear-shaped diamond, which has stayed on the fourth finger of my left hand for almost 32 years. The ring has come off only once in all these years, when the back had worn so dangerously thin that I took it to the jewelry store for repair. Like marriage, it needed fortifying after so many decades. Without question, we’ve had a good marriage, not perfect by any means, but very real, filled with love, laughter, and true friendship. In the heat of an argument, the “D-word” may have been thrown around, but never as anything more than just a weaponized word meant to temporarily wound.

So did I want to get divorced? “Of course not,” I answered, unsettled by the question and completely surprised by what followed. “I’m thinking about buying grave plots,” he said matter-of-factly. “And you can’t return them or put someone else in them once they are deeded.” He paused. “I guess what I’m trying to say is: Will you take my hand in death? We accepted our vows of until death do we part, but I’m wondering, will you spend eternity with me?” “Yes,” I said, feeling relieved. “Yes!” Strange as it sounds, it was one of the most romantic things he’d ever said to me.

Of course, it’s a timeless truth that nothing lasts forever, and we’re not about to be the exception to that rule. But thinking about us together, truly forever, in the historic arboretum-cemetery where his mother is buried now—not far from where we were raised and first fell in love—keeps me moored and feeling acutely alive in the present. For the most part, ours has been a lucky life, with joy greatly outweighing the sorrow. More than three decades later, our three kids are grown and mostly gone. And the reward of a long marriage and a lifetime of hard work is that it’s our turn now—to see the world, then revel in the table set for two back at home, where we continue to contemplate our future together. At 55, it all feels more urgent than ever.

I can’t say for certain that I believe in heaven or the afterlife, nor am I convinced that my soul will rise when my consciousness ceases to exist. I’ve been a bit of an overachiever in life, though I don’t expect to distinguish myself in death. I don’t know what waits for me when the lights go out, but I am comforted by what I do know now: My beacon will be by my side, the person who loved me with all of his heart while mine was still beating, the person who loved me enough to share not only a lifetime together, but whatever comes after. We’re in deep, six feet to be exact, together forever, wherever life—and death—take us.