Health & Wellness

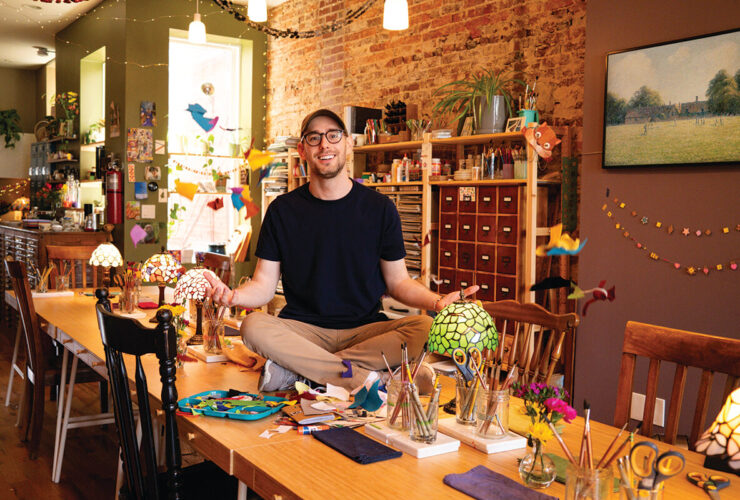

They’ve returned to work, shift after shift, for more than 30 years. Four veteran nurses at local hospitals share their stories.

ne day in the 1980s, Connie Silberzahn was tending to a patient in Greater Baltimore Medical Center’s (GBMC) surgical Unit 41 when a surgeon requested Bard Parker at the bedside. Very early in her nursing career, she assumed Parker was another doctor and rushed to request a page from the hospital operator. Moments later, “Bard Parker to Unit 41! Bard Parker to Unit 41!” echoed overhead. When she returned to the patient’s room empty-handed, the surgeon looked at her quizzically. Pulling her aside, he explained, “Bard Parker is the name of a scalpel, but I don’t like to say ‘scalpel’ in front of my patient.”

Silberzahn recalls blood rushing to her cheeks in embarrassment as she hustled to retrieve the scalpel, noticing for the first time the tiny letters stamped into its stainless-steel handle.

Forty years into her nursing career, Silberzahn, 61, is still working night shifts in the same unit at GBMC. Her early-career mix-up has become a favorite anecdote to put new nurses at ease and remind them it’s okay to ask questions. It’s even made its way into Tales at the Bedside, a team meeting where seasoned nurses share their experiences with recent grads as part of the hospital’s yearlong residency program.

Whether through formal programs like at GBMC or through tips and advice shared at the bedside, learning from seasoned nurses is essential to the success of their newest colleagues. Mentorship not only improves patient care outcomes, it also helps with nurse retention. But many of the owners of that essential knowledge are hanging up their scrubs.

Across the U.S., about 100,000 registered nurses left the workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic due to stress, burnout, and retirement. With the average age of RNs at 52 years old, that wave is expected to continue—the National Council of State Boards of Nursing estimates one-fifth of RNs nationally will retire by 2027.

It’s a similar story in Maryland. Existing shortages from the pandemic will be exacerbated by aging nurses retiring and an aging population in general, increasing the number of patients in need of care. The Maryland Hospital Association projects a shortage of 13,800 full-time RNs and 4,000 licensed practical nurses (LPNs) by 2035, resulting in a workforce only able to meet about 80 percent and 44 percent of demand, respectively.

This makes nurses like Silberzahn who have stuck around for the long haul even more valuable. They have weathered a changing industry and bring decades of experience to each shift.

“I was very nervous, even though I had been a nursing assistant on the floor,” Silberzahn says, recalling her first shift as an RN. “I was a bit overwhelmed and felt like I had to know everything and do everything perfectly, but at the end of the shift I remember thinking, ‘I did it. I made it through.’ The patients were very kind and appreciative. So that made it easier to go in the second day, and the third day.”

She sees a similarity with her newest colleagues. “You can see a look of fear in their eyes when they come in, so I try to make it easier any way I can.”

As a child, nurse Sheila Lee spent time with many elderly relatives and neighbors in West Baltimore living with multiple medical problems. That experience inspired her career path.

“I always had a passion to make a difference by helping them to manage their health-care problems and medical conditions,” Lee recalls. More than four decades later, Lee drives 30 miles each way from her home in Abingdon to care for patients in the same part of Baltimore where she grew up. While some patients at the University Health Center, an outpatient clinic at the University of Maryland Medical Center, travel from out of state to receive the specialty care it offers—especially transplant services—many are residents of the surrounding West Baltimore community.

“I just love working with this population because I get to work with people from my community, and I know there’s a great need,” Lee says.

Over the past four decades, Lee says, her role as a nurse has grown alongside the understanding of social determinants of health, or how socioeconomic issues—such as housing, transportation, and food insecurity—impact an individual’s overall health outcomes.

“If you don’t know where your next meal is coming from or have a place to stay, you may not be able to keep your doctor’s appointments,” she explains. In response, Lee and her colleagues have learned to be nimble, prepared to address other acute needs beyond care associated with the visit itself. “We provide many community resources and make referrals to other agencies, food pantries, housing—whatever the need is.”

Making an impact in patients’ lives keeps Lee, 62, motivated. In her current role at University Health Center—and before that, for 20 years at the Evelyn Jordan Center (now known as the THRIVE Program) working with patients who had HIV/AIDS diagnoses—Lee developed close relationships with patients she saw frequently over the years. “It was rewarding for me because I was able to impact the health and wellness of patients who had limited resources or support,” she says. “Many became like family to me.”

Like Lee, Sherry McGraw, a nurse at Sheppard Pratt with nearly 50 years of experience, felt drawn to the profession at an early age. But it was as a student at Essex Community College in the early ’70s, when she had the opportunity to interact with patients in the psychiatric unit at the Perry Point VA Medical Center, that she discovered her true calling.

“I’ve always liked psych and I wanted a challenge,” McGraw, 70, says. “I always liked talking to the patients, and what really gets my heart is when I feel like I’ve reached somebody.”

Over the years working in Sheppard Pratt’s thought-disorders unit (for patients experiencing psychosis) and the co-occurring disorders unit (for patients experiencing more than one mental health condition), McGraw has learned how to gain patients’ trust to more effectively care for their needs.

“As a psych nurse, you have to have very tough skin,” McGraw says. Part of her role is evaluating new patients upon intake and assessing their needs—such as rating withdrawal symptoms—for the doctors. Nurses like McGraw help patients work through the fear, anxiety, and anger that often accompany the intake and recovery process. McGraw’s been called names and even knocked to the floor by patients experiencing hallucinations or detoxing. But decades of experience have taught her that approaching each patient with compassion and consistency yields the best results.

“I don’t judge,” McGraw says. “Eventually, they’ll open up. I tell them, ‘This is the first day of the rest of your life. Take a calendar, mark this day, and be proud.’”

With trust established, much of McGraw’s work turns to education—about recovering from addiction, practicing coping strategies, and staying healthy so they can get back to their families and their lives. McGraw’s motivation to keep showing up for her patients after more than five decades has recently become even more personal. Her daughter, Rachel, died of accidental fentanyl poisoning in 2019.

“Thinking about my daughter, I just want to help people. That’s why I work so hard with my patients. I want them to live.”

She feels her impact most through the patients she doesn’t see again—hopefully, an indication of sustained recovery. “I’ve had patients say, ‘When I leave here, I’m going to give you a present.’ I tell them just getting better is my present,” McGraw says. “Every once and a while, someone will call to let me know they are doing great. I love that.”

It’s affirmation like that that encourages many nurses to stick at it for decades, despite the physical and emotional demands of the career. They cite other reasons, too, from flexible schedules allowing them to raise a family to opportunities to continuously learn through professional development, and colleagues who become as close as family. But most often, they point to the genuine connections with patients and the impact they can make in the lives of others.

The career’s flexibility made it possible for Carol Durkin to care for a family and continue working at MedStar Union Memorial Hospital’s medical-surgical unit. Her husband, a teacher, worked during the day, and by taking the night shifts—three 12-hour shifts from 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. each week—her family could avoid paying for childcare. She got so used to the schedule, she’s maintained it.

Looking back, Durkin, 66, says the time has passed quickly. While she’s worked in the same hospital for four decades, the variety of each day and the need to continuously learn kept her interested. But the patient interactions are what keeps her coming back each day.

“Sometimes, when the techs are busy, I’ll go in and give a bed bath,” Durkin says. “It’s nice to talk to the person and get to know them. I enjoy that part of it.”

She’s so drawn to her work, the Catonsville resident suspects she’ll return even in retirement. “At that point, I’m going to just do the comforting part of the nursing. I’d like to volunteer with our church to feed people and that kind of thing, because that’s the part that I really, really enjoy now.”

Durkin remembers the important role experienced nurses played in her growth as a young RN fresh out of nursing school in the early ’80s. “There were nurses who had been there for a lot of years, and they helped me out when I got overwhelmed,” she says.

Today, she provides that same calming presence for her younger colleagues.

At GBMC, Silberzahn’s legacy is continuing in a more direct way: Her daughter, Megan, is a charge nurse on the hospital’s same-day surgical unit. While they don’t work together directly, Silberzahn occasionally hears stories from colleagues who interacted with her daughter earlier that day.

“I’m so proud of her. She’s worked so hard to get where she is,” Silberzahn says, noting they often call each other on the drive to or from work to catch up about what happened during their shifts. “When I talk to her now, she is not just my daughter, she’s another nurse.”