Science & Technology

This State-of-the-Art Hatchery is Sowing the Future for Chesapeake Bay Oysters

Ferry Cove Shellfish near St. Michaels is making a major impact on the region’s farm-raised seafood.

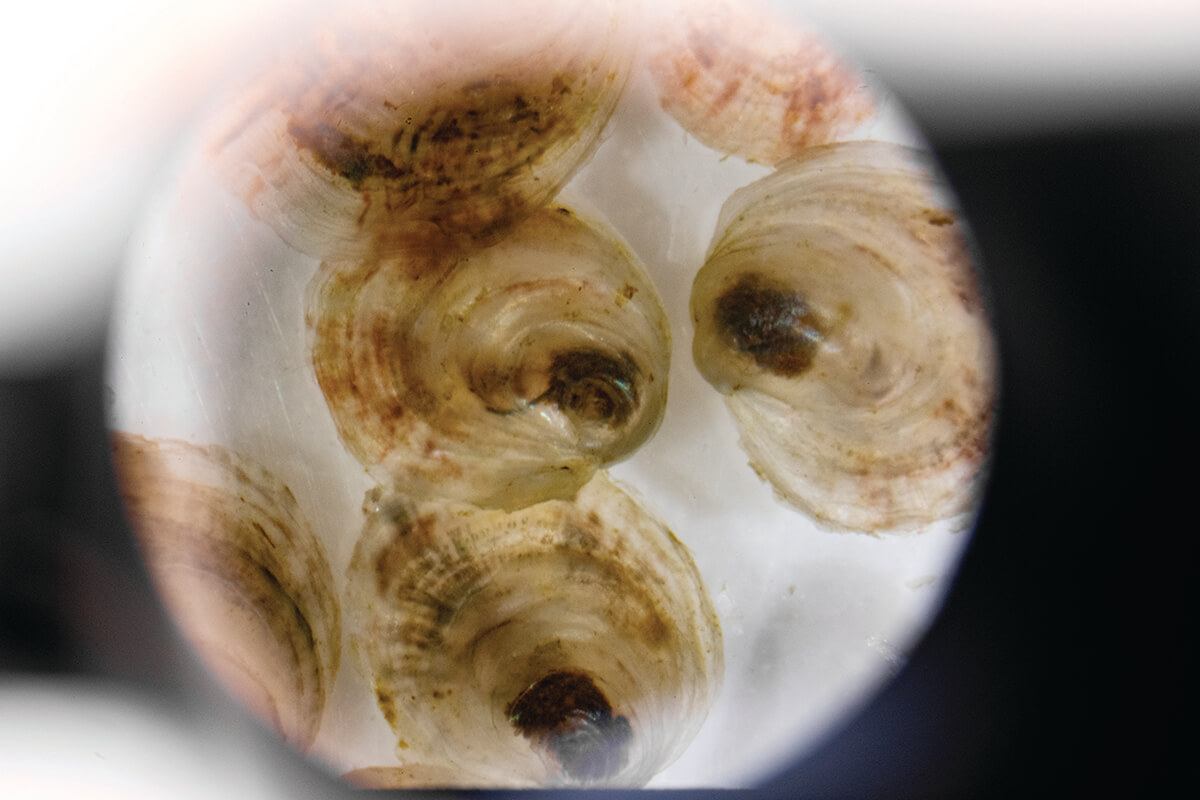

A few-days-old fertilized oyster larva is no bigger than a speck of dust. But under a high-powered microscope, a fully formed mollusk is visible, complete with a teeny tiny shell and miniscule “foot” that, when ready, will attach itself to the oyster’s forever home.

In the wild, oyster larvae are vulnerable to the countless whims of Mother Nature. But raise them in a man-made hatchery, with the right balance of temperature, water quality, and a gourmet diet of algae, and they will grow into tiny “seed” oysters.

Like a farmer purchasing soybean seeds for planting, healthy larvae and seed oysters are vital for watermen and aquaculturists who will plant them in the Chesapeake Bay, where they’ll be raised to fulfill their destiny on plates across America. On their way to beds of crushed ice or to be fried and tucked into po’ boy rolls, these tiny oysters will play an outsized role in water quality, habitat creation, and economic development.

For many seed oysters in the state of Maryland, that journey now begins at Ferry Cove Shellfish. It is the state’s newest, most state-of-the-art private hatchery—the only one in Maryland operating as a nonprofit. And it is poised to have a major impact on the region’s shellfish aquaculture, the process of farm-raising seafood.

In 2025, it successfully produced two billion oyster larvae from its location in the hamlet of Sherwood near St. Michaels, where the waters of Eastern Bay flow into Poplar Island Narrows. Ferry Cove’s building is nestled between a wildflower meadow and a veritable forest of native grasses, which president and CEO Stephan Abel’s dog, Petey, happily disappears into when given half a chance.

The water flowing around Poplar Island was part of the appeal of this spot, says Abel, who lives in Annapolis. He had access to 20 years’ worth of Army Corps of Engineers data from their restoration of nearby Poplar Island.

“So I knew what the water was here,” he says. Like good soil for plants, “having the right water is paramount.”

The fact that a 70-acre parcel was available there—and close enough to sizeable towns like Easton to entice a strong workforce—sealed the deal.

Much of the acreage is leased to a local crop farmer, but there’s also a weather station installed in partnership with the University of Maryland (UMD), a sea-level rise monitoring system, and an ongoing shoreline restoration project. Tanks and cages near the waterline are evidence of a facility used by the Maryland Seafood Cooperative, which supports watermen new to aquaculture.

These projects aren’t just about environmental altruism. Weather, water temperature, rising tides—it all impacts the oysters. The health of these bivalves often corresponds with the health of the Bay, and vice versa.

“We are the applied science,” says Abel. “We come at it from the industry perspective—the aquaculturist’s or waterman’s perspective—listening to what they need, working with researchers, and then developing products.”

Abel is an unlikely aquaculturist. A Philadelphia native, he grew up sailing every summer on the Chesapeake. But the extent of his oyster knowledge was that they taste good served with a wedge of lemon.

He began his career in the military, moved to the dot-com glamour of the late ’90s, then, after the boom, landed a job at the Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR). From there, he went to the Oyster Recovery Partnership (ORP), where he served as executive director for 13 years.

His tenure corresponded with the state’s creation of an Oyster Advisory Commission tasked with developing a road map for restoring the native oyster. Years of over-fishing, habitat degradation, and disease reduced Maryland’s annual oyster haul from one to three million bushels in the mid-20th century to a few hundred thousand today. The plan included money to train watermen in aquaculture; Abel worked on those training programs at ORP.

The benefit of aquaculture is that wild fisheries are open October through March. But farmed oysters are available year-round. Problem was, even as aquaculture was being promoted, there was a seed shortage. There are a handful of small, private hatcheries in Maryland, but most larvae come from the UMD Center for Environmental Science’s Horn Point Oyster Hatchery. As a state entity, it was producing most of its larvae for Bay restoration projects, with only a small amount for commercial use.

Abel saw a need in the market for consistent, reliable access to seed.

“I also saw that the future of shellfish restoration is limited, because government money can only go so far,” he says. “My mind shifted from bulk restoration to ‘how do we get more oysters in the Bay that not only benefit the Bay, but also benefit the local economies and local industry?’ And that’s aquaculture.”

The hatchery opened in 2021, thanks in large part to investment from the Philip E. and Carole R. Ratcliffe Foundation. Inside, the waterfront idyll is replaced with pristine water tanks and modern technology, more like a scientific research lab than a nursery.

Hatchery manager Steven Weschler stands under a large screen where every tank’s water quality is managed via a computerized system. He walks to the brood stock room, where wild oysters pulled from the Bay are kept at 68 degrees and fed a nutrient-rich diet of algae before moving to spawning tables, where the water is heated to a balmy 85 degrees to facilitate the release of sperm and eggs. Heavily filtered water from the near shoreline fills the tanks.

Once fertilized, larvae move to rearing tanks where they are watched carefully for the emergence of an eye spot and a foot—a sign they’re ready to attach to shells. Some larvae will be sold to local watermen—they’re microscopic; more than one million fit in a Dixie cup. The aforementioned foot will attach to shells and be planted as “spat,” aka adolescent oysters, in the Bay. Grown naturally in the Bay, most are destined to be shucked and jarred.

Other larvae are circulated with finely pulverized shell at Ferry Cove. As they grow, the oyster attaches to the microscopic shell, becoming stand-alone oyster seed—two-to-four millimeters each in size—destined to be grown by aquaculturists in mesh bags placed in cages. They will grow into the deeply cupped variety that’s appealing to serve on a plate.

These are the kind raised by Tal Petty, the founder of Hollywood Oyster Company in St. Mary’s County. He buys millions of seed from Ferry Cove, which allows him to harvest 52 weeks a year. Not surprisingly, he values that the product is consistently available. What excites him, though, is that while aquaculture oysters are specifically raised to be sold, any oyster put in the Bay plays a part in its health.

Petty sets his oyster cages on a hard sandy bottom in Hog Neck Creek. “You put a cage of oysters in the water, you pull it back out a couple months later, it’s teeming with eels, fish, algae…You’ve created a water world where there was a desert before,” he says.

While rearing larvae is an intricate process at Ferry Cove, farm-raising oysters is just as arduous. Patrick Hudson, owner of the True Chesapeake Oyster Company, explains that buying from Abel allows the farmers to concentrate on what they do best—raising delicious oysters. His oysters travel from cages in Southern Maryland to Whole Foods, Harris Teeter, and restaurants across the Mid-Atlantic, including their own, True Chesapeake in Hampden.

“Producing healthy, reliable seed suitable for aquaculture is incredibly complex,” says Hudson. “Ferry Cove brings cutting-edge technology and valuable science to that process, giving us strong, consistent seed we can depend on.”

Ferry Cove’s efforts have been welcomed by traditional watermen as well. Jeff Harrison, president of the Talbot Watermen Association, has been working the water for decades. He explains that even old-school watermen see the value in hatchery-raised product; they use spat-on-shell larvae in restoration projects that are planted each spring. This helps rebuild wild oyster reefs for watermen to harvest.

“Ferry Cove was born out of the realization that Horn Point couldn’t keep up,” he says. “[Ferry Cove] is going to be a savior not only to aquaculture but the public fisheries as well.”

After decades of decline, oysters are staging a comeback. The DNR estimates there were more than 12 billion oysters in Maryland’s waters in 2024. Sanctuaries (where oysters cannot be harvested) have proven successful, and the bivalves are showing signs of resistance to diseases that once decimated them.

Michael Roman witnessed that resurgence first-hand as the director of Horn Point from 2001 to 2023. He says the importance of aquaculture was always apparent.

“If you go to Massachusetts and Maine or Washington state, aquaculture is the dominant way to get oysters,” he says.

He explains that there are parts of the Bay where wild oysters would sink into the muddy bottom, but they can grow in aquaculture float cages. Thus, “Aquaculture has maximized and expanded the potential of oysters in [the] Bay.”

Today, Roman is on the Ferry Cove board of directors. He wanted to bring his experience to the growing enterprise and, given that it’s a nonprofit, “It’s almost like it’s a hybrid between a private, for-profit hatchery as well as a place that does experiments,” says Roman. “[It does] more than figure out ways to improve the way they produce oysters.”

Abel says the hatchery is called Ferry Cove Shellfish for a reason. Right now, it’s working with academic partners on ways to re-invigorate the soft-shell clam and even how to raise soft-shell crabs via aquaculture. They are also experimenting with fabricated shell to set larvae on, as finding the recycled real stuff is difficult and expensive.

“The goal is to support aquaculture by providing the industry with [oysters] primarily, but then expand to other shellfish with the focus on providing entrepreneurial opportunities, supporting rural parts of Maryland, and then also looking at different ways to help restore the Bay,” Abel says.

The value of shellfish aquaculture is rising. The DNR estimates the economic impact in Maryland is more than $13 million per year. Cassandra Vanhooser, director of economic development and tourism in Talbot County, explains that for the more than 500 working watermen in the county, “Ferry Cove is essentially supporting jobs.”

And oystering is a heritage industry, part of the cultural fabric that gives the area its sense of place.

“When I go to Ferry Cove, I see the future,” she concludes. “Their work marries science and heritage—strengthening our working waterfronts, enhancing oyster restoration, and expanding a vital, sustainable industry.”

That industry will increasingly lean on private enterprises like Ferry Cove as federal and state funding become less reliable, says Harrison.

“And this is when we need funding, because the Bay is doing better,” he says. “We just need more money to put more things overboard. Then maybe the Bay can get back to how it was when I was a kid.”