Sports

Season of Suck

Fifty years ago, the Colts, O’s, and Bullets all fell to upstarts from New York when it mattered most.

Boog Powell had the best view of anyone at a packed Shea Stadium. The O’s slugger had just singled Frank Robinson to third and stood at first base as the potential go-ahead run in the top of the ninth. Only two teams in modern Major League history had posted more regular-season wins than this ’69 Orioles club—the legendary ’54 Indians and ’27 Yankees. But at this confounding moment, Powell and his teammates trailed the New York Mets 1-0 in pivotal Game 4 of the 1969 World Series. More disconcerting: They also trailed the previously laughingstock Mets, who had never finished better than ninth place in the National League, 2-1 in the series.

With two runners on base and one out, Brooks Robinson, who had more All-Star appearances (10) than the Mets had seasons (7) under his belt, stepped to home plate to restore order to the universe. New York manager Gil Hodges slow-walked to the mound to buy time for his fading young starter, but to no avail. On cue, Brooks ripped Tom Seaver’s next delivery into the vast green ocean in right center field. With the ball whizzing by in front of him, Powell took off for second.

Watching clips of the game on YouTube a half-century later, it’s still hard to believe Robinson’s line drive does not hit the turf, skip off the warning track, and bounce to the fence. But out of nowhere, diving headlong into NBC’s shot, comes Ron Swoboda, an outfielder nicknamed “Rocky” because of his less-than-smooth reputation with the glove, who proceeds to make what is possibly the greatest catch in World Series history. Certainly it is the catch of his life—a full-speed, belly-up, lose-your-cap plunge across the Shea grass. As Swoboda staggers to his feet—the 396-feet sign visible on the outfield wall behind him—and improbably finds the ball in his mitt’s leather webbing, Frank Robinson tags and scores from the third. The O’s rally, however, has been thwarted.

“I’ve seen the replay dozens of times,” Swoboda recalls with a laugh. “You know who isn’t in the picture? [Center fielder] Tommie Agee, who was playing Brooks to pull. It was ‘do or die,’ and 99 percent of the way there I didn’t think I was going to make it.”

“Oh, I remember the catch,” Powell says. “I can see it like it happened yesterday. What I don’t remember is how I reacted. I don’t know if I stopped dead halfway between first and second or tried to get back to the bag. I was stunned. Mesmerized.” Destiny on their side, the Mets won on a controversial bunt play in the 10th. After another break from the umps in Game 5—known since as “The Shoe Polish Incident” (Google it)—Swoboda, a fun-loving, career .242 hitter, finished the Orioles with a go-ahead-to-stay double.

That it was the unlikely Swoboda who struck the mortal blow to Baltimore’s last, best hope of a championship in 1969 proved the perfect, fluky capstone to the most heartbreaking year in the annals of professional sports. He was a Sparrows Point kid who grew up going to Memorial Stadium. Brooks Robinson was his favorite baseball player.

“Listen, I worshipped the Orioles and Colts. I still have a John Unitas-autographed Colts helmet in my office,” Swoboda says. “To this day, I practically genuflect every time I walk past it. Fifty years later, it still burns me up they didn’t bring him in earlier in the Super Bowl that year.”

Yes, the 1969 Super Bowl. We’re getting to that.

Heading into the Super Bowl, NBA playoffs, and World Series in 1969, the Colts, Bullets, and Orioles had each posted the best regular-season record in their respective sports—a feat never accomplished before or since by a single city’s franchises. The Colts went 13-1 and redeemed their only loss (to Cleveland) with a 34-0 thrashing of the Browns in the NFL title game. The Colts and the O’s—who topped the Major Leagues in pitching and fielding and finished third overall in runs scored—were bandied about as possibly the greatest teams ever. Maybe they were. But when it mattered most, all three Baltimore powerhouses were soundly toppled in the postseason by underdog squads from the Big Apple.

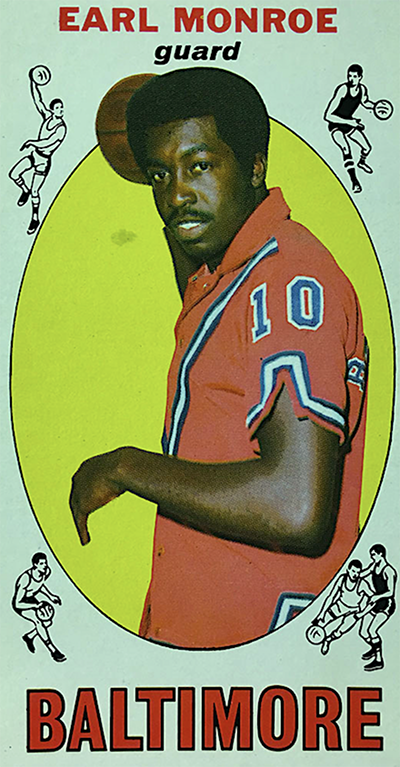

In January, favored by 18 points, the Colts were upset by the New York Jets of the second-string American Football League. In March, Wes Unseld, Earl “the Pearl” Monroe, and the Bullets were swept in four games by the Knicks. Then, in October . . . where do you begin? For most of the season, the Cinderella Mets lineup averaged 24 years old. (“The last miracle I did was the 1969 Mets. Before that, I think you have to go back to the Red Sea,” George Burns cracked in the movie Oh, God!)

“Not a very good year for Baltimore, was it?” sighs Powell, who knew some of the Colts—the O’s shared the same workplace after all—and watched his buddies lose Super Bowl III from the sidelines in Miami.

Local scribes had a diagnosis for the city’s sports woes: “The New York Syndrome.”

The City That Never Sleeps was a darker place in the 1960s, struggling with poverty, crime, racial strife, and conflicts over the draft and the Vietnam War, like most cities, including Baltimore. But New York also remained exciting and seductive. It was still Broadway, Wall Street, Frank Sinatra, pop art, mod fashion, and Greenwich Village. (Good luck staying awake all night after a shift at Beth Steel or General Motors.) “Tug McGraw and I were naïfs when we arrived in New York,” Swoboda says. “We’d walk around during the day staring at the skyscrapers, talk our way into the audience of The Tonight Show, and then take the subway to the ballpark.”

It certainly wasn’t like that in hardscrabble Baltimore, which acclaimed New York sportswriter Pete Axthelm described as a “dreary city.” Perhaps, although at the time no one imagined a third of the city’s population would flee over the next three decades. Pockets of civic pride and hope remained in Baltimore’s neighborhoods, and it’s not a stretch to say that much of that public optimism was tied to the blue-collar city’s dominating sports teams.

“Oh, we wanted to kill Joe Namath,” recalls former Colt star Tom Matte.

“We have a tendency, and did then, to measure ourselves against New York,” says longtime former Sun columnist Michael Olesker, the author of five books about Baltimore, then a 23-year-old reporter with the Baltimore News-American. “It’s glamorous, and we’re a little insecure about our working-class roots. The Colts were Sunday religion, and 1969 was going to be ‘The Year of the Three Earls’—Earl Morrall, Earl ‘the Pearl,’ and Earl Weaver.” (For non-Baltimore sports historians: Morrall, playing in place of injured Hall-of-Fame quarterback Johnny Unitas, had won the NFL MVP award; the aforementioned Monroe averaged nearly 26 points per game for the Bullets; and the feisty, foulmouthed, diminutive Weaver, of course, managed the Orioles.)

But it didn’t turn out that way.

Ever since free agency entered pro sports in 1976, the teams have become fairly homogenized. Players move from city to city. The Baltimore Ravens are not really from “Baltimore.” They’re a professional football team who happens to play here. Not the case when Unitas, Tom Matte, the Colts’ all-purpose back who spent his entire 12-year career here, the great tight end John Mackey, and all the rest lived in Baltimore, worked at Black & Decker and Sparrows Point, and sold liquor in the off-season. They raised families here. They were part of the community fabric.

In that environment, Unitas’ crew cut, high-top black cleats, and no-nonsense demeanor meant something to a town that valued substance over style.

Conversely, “Broadway Joe” Namath wore a Fu Manchu mustache, expensive suits, mink coats, white cleats, and dated New York actresses. He was the first rock star football player. Sports Illustrated followed him around and chronicled his late-night exploits in a piece titled, “The Sweet Life of Swinging Joe.” He was cocky. Braggadocious. A hedonist anti-hero straight out of Easy Rider, which had been released in the summer of ’69. Namath, like Muhammad Ali, did not play well in Baltimore in those days, when the city was a more of conservative, Southern town.

“Oh, we wanted to kill Joe Namath,” says Tom Matte.

At a dinner given by the Miami Touchdown Club before Super Bowl III, glass of scotch in hand, Namath—18-point spread be damned—responded to a heckler with his famous boast: “We’re gonna win the game. I guarantee it.” The next morning, The Miami Herald dutifully ran “Namath Guarantees Jets Victory” on the front page of its sports section, creating a firestorm. Then Namath repeated his decree when confronted by Lou Michaels, a Colts defensive end and kicker, nearly starting a brawl. This was after Namath, who from the photos appeared to be spending the week lounging by the team hotel’s pool, told a reporter he thought five AFL quarterbacks were better than Morrall—including himself and his backup, Babe Parilli.

It is suffice to recall that Morrall blinked in the klieg lights, heaving three interceptions and failing to see wide-open Jimmy Orr waving his arms in the end zone. The Colts, cut down 16-7, were shut out until the sore-armed Unitas, who also threw an interception, was called upon in the fourth quarter. Namath, named MVP, went on to star in a biker movie with Ann-Margaret, take Raquel Welch to the Academy Awards, and shoot a shaving cream commercial with Farrah Fawcett.

The silver lining? There wasn’t one.

The Colts went 8-5-1 the following year and missed the playoffs. “We were embarrassed, we had embarrassed the whole NFL,” Matte says. “And everyone took it out on us following year.”

“To lose three times to teams from New York was a dagger to the heart. A bloodletting.”

Though it is less remembered because an equally precocious Knicks team sideswiped them in the postseason, the Bullets were the feel-good story in Baltimore in 1969. The Colts and O’s had championship track records. But the year before the Bullets won the most games in the NBA—topping the likes of the Bill Russell-led Celtics and Wilt Chamberlain-led Los Angeles Lakers—Baltimore had finished last in the Eastern Division. The year prior, they were the worst team in the entire NBA—by 10 games.

After the back-to-back basement finishes, they lost the coin flips for the first pick in the draft, too. A blessing in disguise, however. Monroe, taken with the second pick in ’67, and Wes Unseld, taken with the second pick in ’68, each earned Rookie of the Year honors (and Unseld took home the MVP trophy as well). The Bullets leapt from 20 wins to 57 in the process. “I liked to say we lost the coin flip, but won the toss,” recalls former Bullet public relations man Jim Henneman, another longtime Baltimore sportswriter.

With Monroe’s whirling dervish act and Unseld’s length-of-the-court outlet passes, the Bullets became one of the most colorful, fastest-paced, and highest-scoring teams in the league overnight. The Knicks, also an up-and-coming team, had a better bench, however. They trounced a bruised, road-weary Bullets squad by double-digits in the first two games of the opening round of the playoffs.

The much-anticipated series was over before it had started, as were the dreams of a first-ever NBA title in Baltimore. “The NBA All-Star Game had been in Baltimore that January, too,” Henneman remembers. “But it was a bittersweet end to the season.”

In a Greenmount Avenue barroom near Memorial Stadium, Mayor Tommy D’Alesandro III watched Mets left fielder Cleon Jones cradle Davey Johnson’s fly ball and put the World Series—and Baltimore’s three goose eggs—in the books. There were no signs of shock in the subdued tavern, just resignation, and the sense of a familiar tragedy being played out.

“I’m getting used to it,” D’Alesandro told a New York Times reporter on hand, as he drafted yet another good-loser telegram to New York Mayor John Lindsay. “They were making unbelievable plays. I’m going to call a legislative [conference] and see what I can do about an ordinance forbidding Baltimore teams to meet New York teams after the regular season is over.”

Olesker was born in the Bronx, but he moved to Baltimore as a child and grew up a diehard fan of all three local teams. Six years out of City College high school, he took the accumulative losses with less humor than the mayor.

“To lose three times to teams from New York, oh boy, that hurt,” Olesker says. “That was a dagger to the heart. A bloodletting.”

In hindsight, 1969 was a weird year. Strange juxtapositions made it appear the country was being yanked apart at its seams. In January, Richard Nixon was inaugurated and in March, John Lennon and Yoko Ono began their Bed-In For Peace. In July, Neil Armstrong walked on the moon. The next month, Woodstock rocked Max Yasgur’s dairy farm in upstate New York. In October, massive demonstrations—the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam—coincided with the afternoon start of Game 4. Mets Fans for Peace handed out flyers with Seaver’s image, highlighting the pitcher’s recent anti-war remarks.

In the context of the sports world, Baltimore’s postseason debacles proved more of a blip than anything else.

The O’s would come back and win another staggering 108 games the following season and dismantle Cincinnati’s Big Red Machine in the 1970 World Series. “Weaver rode us like the whole way like a jockey down the stretch at Pimlico,” recalls Jim Palmer, the O’s Hall of Fame pitcher. After taking their licks following their humiliating defeat to the Jets, the Colts rebounded and won Super Bowl V.

Meanwhile, the Bullets and Knicks continued one of the fiercest rivalries in sports. In 1970, the Knicks, on their way to their first title, bested the Bullets again in the playoffs, but in seven games. The match-ups were epic: Unseld vs. Willis Reed, Gus Johnson vs. Dave DeBusschere, Jack Marin vs. Bill Bradley, Monroe against Walt Frazier, Kevin Loughery against Dick Barnett. The next year, in the Eastern Conference finals, the Bullets broke through and beat the Knicks in seven games.

Of course, nothing lasts forever. As thrilling as they were, the Bullets didn’t draw. The Civic Center wasn’t a great venue and, in the wake of the ’68 Baltimore riots, a lot of fans decided to stay home. Unseld’s uniform still read “Bullets” when they finally won an NBA title in 1978, but now he played in Landover for the Washington Bullets. In 1972, Colts owner Carroll Rosenbloom traded the team to Robert Irsay, and after a flurry of division titles in the mid-’70s, well, we all know how that ended.

By the 1970s, deindustrializing Baltimore was folding under the weight of soaring unemployment, crime, interest rates, and subsidized white flight. Quickly shifting from a segregated, majority-white city to a majority-black city, the social upheaval had been acute during the previous decade.

“Those teams, the Colts and Orioles, in particular, and the Bullets bound the city together through difficult times,” says Olesker.

It was a two-way street.

When the Orioles lost in Game 5 at Shea Stadium, delirious Mets fans rushed the field. In the midst of spontaneous celebrations across New York, the O’s players still had to make their way back to Baltimore. “Shea was going crazy,” recalls Powell. “We had to pack everything up and then deal with some obnoxious fans as we got on the bus to the airport. Nobody really said a word the whole way. It was quiet. Same thing on the flight home.”

Flying into Friendship Airport (now BWI) that evening, Powell was exhausted, dispirited. The Orioles had scheduled a shuttle bus to take most of the players to Memorial Stadium to pick up their cars—the burly first baseman lived in a rowhouse five blocks away in same neighborhood with Dave Johnson and Eddie Watt. He was fond of firing up his backyard barbeque on nights the O’s won. The off-season would be long.

“So, we get off the plane and 5,000 fans are there to greet us, cheering,” Powell recalls. “No cell phones in those days. We had no idea. You can check it—I don’t know if it was 5,000—it might have been 20, but I know the way I felt, it seemed like 5,000. We went toward them, reaching through the fence to shake hands with everyone who had turned out for us. I know I shed a tear. I don’t think there was a dry eye on the team. You don’t have words for something like that.”

It was, to turn a certain phrase around, the worst of times, it was the best of times.