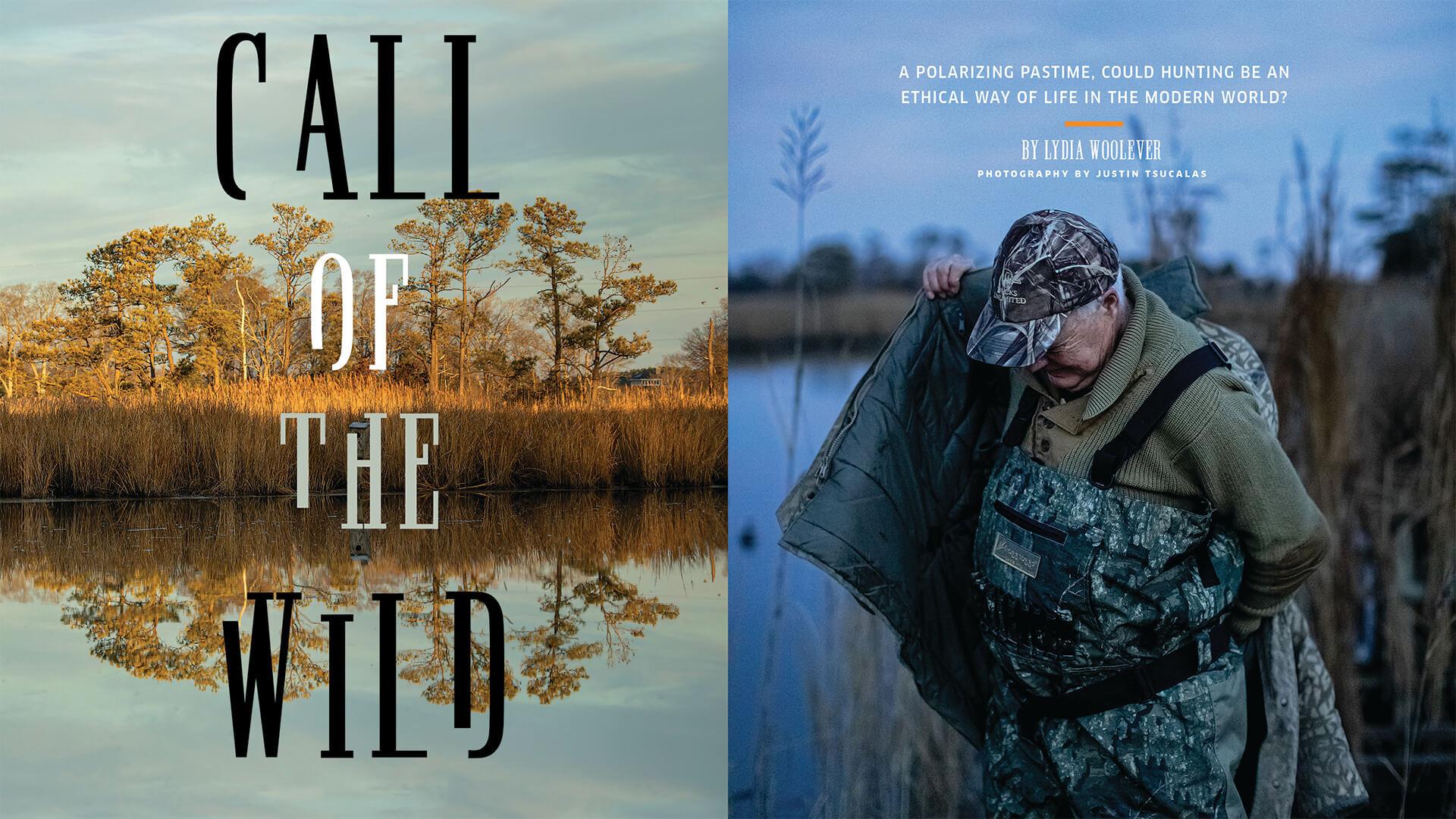

IS STILL DARK AS BO EARNEST parks his

Toyota Land Cruiser in the Eastern Shore woods and

opens the trunk to sling a shotgun over his shoulder.

Through the pines, the first blue line of dawn begins to

break along the horizon, and while he takes his time,

readying his gear and calming his golden retriever,

Ruddy, the plan is to be in place before the light of day.

IS STILL DARK AS BO EARNEST parks his

Toyota Land Cruiser in the Eastern Shore woods and

opens the trunk to sling a shotgun over his shoulder.

Through the pines, the first blue line of dawn begins to

break along the horizon, and while he takes his time,

readying his gear and calming his golden retriever,

Ruddy, the plan is to be in place before the light of day.

Two hundred yards away sits an old blind—a wooden shed of sorts hidden beneath bundles of dried brush meant to blend in with the rest of the brackish marsh on which it sits. Earnest leans his gun inside and wades into the icy waters to set up a spread of plastic decoys, scaring off a few live birds that flutter to another pond on this 1,000-acre tract of land, most of which he has put into conservation easements with organizations like the Nature Conservancy and Maryland Environmental Trust.

Canada geese arrive for winter.

Now, he waits, sitting silently in the blind, bundled up in an olive wool sweater and down-filled camouflage coat, listening for signs of life out there in the marsh. To the unknowing ear, though hard to distinguish, there are many, with perhaps thousands of waterfowl out there afloat in the Choptank River outside of Easton. The chatter of ducks and geese mixes with the chirp of songbirds and bald eagles that flit over the flaxen wetlands on this calm January morning—a bluebird day, as they say, unfortunately for Earnest.

“It’s a bit of a mystery, but the best waterfowling days are when the weather is terrible,” he whispers, picking up one of his duck calls from time to time to lure in a few distant birds, passing on a V of geese that fly too high overhead for a clean shot. “It’s sort of a waiting game. Good for meditation, anyway.”

At about 8 a.m., a pair of teal—two small, colorful, especially tasty dabbling ducks—appear out of nowhere, heading toward the blind. He shoulders his gun and fires two quick shots at the targets that twist and turn like fighter jets around the pond before flying away. Yellow shells fall to the floor as Ruddy becomes antsy, eager to rush the water and retrieve his owner’s catch, like last weekend, when they reached their legal limit before breakfast.

“That’s why they call it hunting, not shooting,” says Earnest, 77, who knows from experience, having chased birds along the Chesapeake since the 1950s. He calls it quits within the hour, heading home empty-handed to a cup of coffee and warmer toes.

Opening photo: Bo Earnest hunts on the Eastern

Shore. Ruddy on the

lookout, eager to retrieve the day’s catch.

n the modern world, there are few ancient traditions

that stir debate quite like that of hunting. For some,

the sheer mention brings to mind images of grinning

men hovered over exotic wildlife, perhaps none more

famous than Cecil the Lion, illegally killed by an American

dentist in Africa in 2015. For others, it is the hobby of backwoods,

beer-drinking gun-lovers, as polarizing a rural-urban divide

as that of national politics.

n the modern world, there are few ancient traditions

that stir debate quite like that of hunting. For some,

the sheer mention brings to mind images of grinning

men hovered over exotic wildlife, perhaps none more

famous than Cecil the Lion, illegally killed by an American

dentist in Africa in 2015. For others, it is the hobby of backwoods,

beer-drinking gun-lovers, as polarizing a rural-urban divide

as that of national politics.

Today, it is estimated that more than 80 percent of the U.S. population now lives in urban areas. But it wasn’t that long ago that hunting was a core part of the American identity, as commonplace as growing a garden or throwing a fishing line, rooted in many ways to a deep connection with the land, as well as the quest toward its conservation.

Hunters gun the Patuxent River, photographed by A. Aubrey Bodine, c. 1942.

Even in rapidly developing regions like the Mid-Atlantic, there are still 114,765 licensed hunters in Maryland. The state’s 3,000 miles of Chesapeake Bay shoreline and sprawling foothills of the Appalachian Mountains have historically made it a sort of hunting oasis—first, simply as an abundant region for its inhabitants, with Native Americans, early colonists, and multiple generations thereafter hunting for sustenance. Then, eventually, with the advent of sport hunting, as a world-renowned destination, drawing several U.S. presidents to its Western rod-and-gun clubs and luring celebrities like Annie Oakley east, to where the Atlantic Flyway migratory path bottlenecks at the bay headwaters for a storied supply of winter waterfowl. Duck and goose hunting along the estuary would give rise to America’s first state dog, the Chesapeake Bay Retriever, and forever imprint the pastime on the watershed’s sense of place.

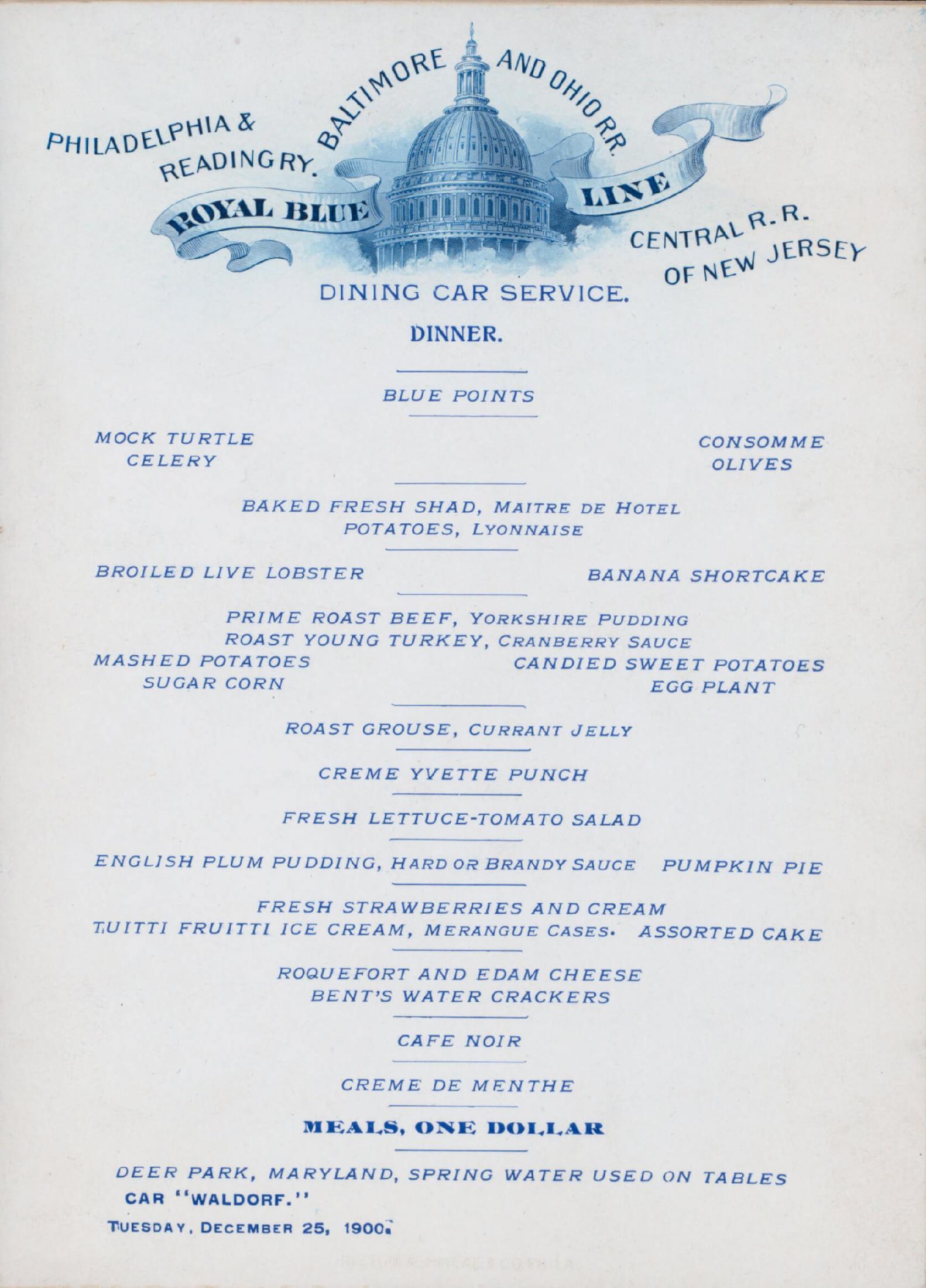

Vintage B&O menu featuring wild game.Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

But by the late 1800s, urbanization and westward expansion had begun to gravely deplete the pristine resources of America’s wild places. To feed fast-growing cities, wild game was feverishly hunted and sold to restaurants, where canvasback duck and terrapin often headlined menus, both of which were nearly hunted to extinction. The feather and fur trade, fueled by the fashion industry, pushed many more species to the brink. In Harford County, market hunters notoriously used “punt guns” the size of small cannons to slaughter up to 100 waterfowl with a single shot, shipping their catch on rail lines to Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York.

“It was a bit like the Wild West,” says Mark Madison, historian for the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, citing the common standoffs between hunting outlaws and federal agents. “The Chesapeake Bay had a lot of poachers. So much so that the Baltimore courthouse had something called the ‘Duck Docket’ of regular ne’er-do-well market hunters.”

These hunters were seen as a different class than sportsmen, who followed a self-imposed set of hunting ethics, such as obeying all laws and attaining shooting skills necessary for the fastest, cleanest kill. It was these hunters who, after noticing sharp declines, lobbied for the nation’s first pieces of federal wildlife legislation, from the 1900 Lacey Act, prohibiting the sale of wild game, to the landmark 1918 Migratory Bird Treaty Act, providing regulation and protection for ducks and Canada geese, as well as countless other un-hunted species.

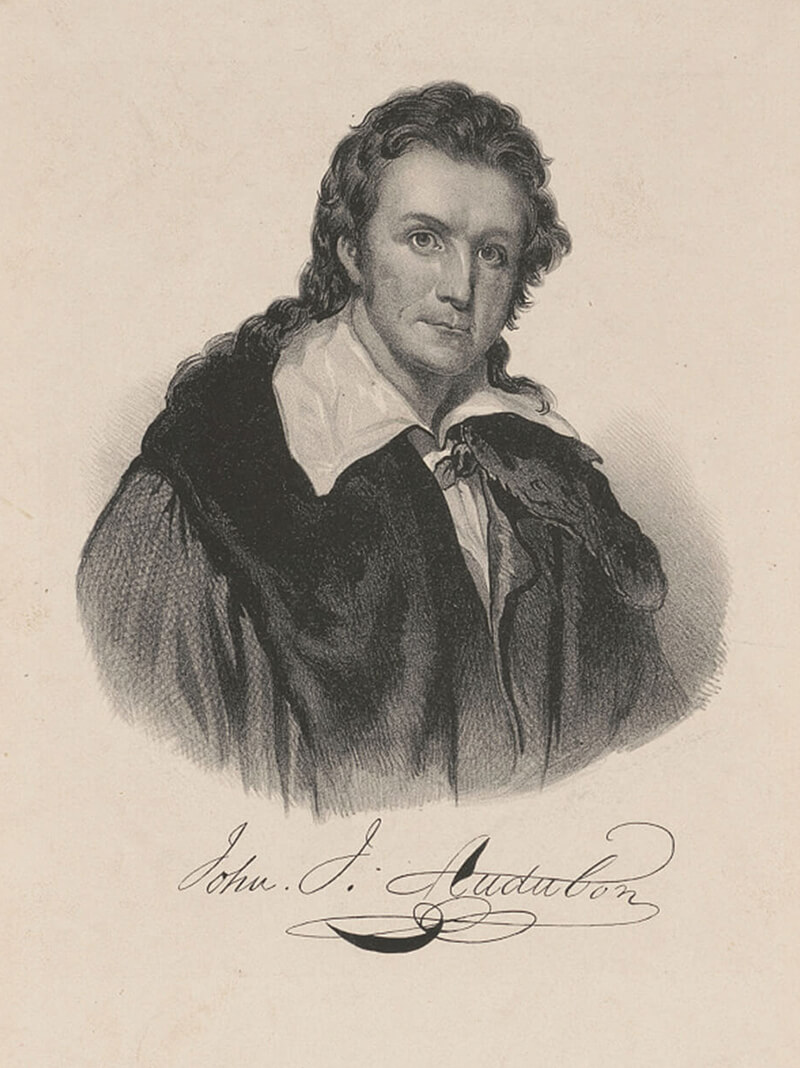

John J. Audubon, c. 1820s. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

“Hunters were some of the first people to realize that wildlife was becoming threatened,” says Madison. “It became harder to hunt bison or elk or turkeys or deer or passenger pigeons. They saw it with their own eyes.”

It might come as a surprise to learn that hunters were indeed some of the earliest American environmentalists, from ornithologist John James Audubon, who depended on hunting for his iconic study of birdlife, to Theodore Roosevelt, the 26th president, who famously shot buffalo and grizzly bears, wore buckskin suits with fur caps, and co-founded of one of America’s first conservation groups, the Boone and Crocket Club.

Inspired by preservationists like Henry David Thoreau and John Muir, who sought to protect nature from human activity, these new hunter-naturalists would help give birth to the budding movement of American conservation, advocating for the same outcome but through responsible use of natural resources.

Theodore Roosevelt in deerskin hunting suit, c. 1885. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

This utilitarian view inspired Roosevelt to establish the National Wildlife Refuge System, the U.S. Forest Service, and five national parks, protecting some 230 million acres that might now be lost to development, and solidifying public access to the great outdoors for all Americans, not just the elite, as it had long been in Europe.

“The excellent people who protest against all hunting, and consider sportsmen as enemies of wildlife, are ignorant of the fact that in reality the genuine sportsman is by all odds the most important factor in keeping the larger and more valuable wild creatures from total extermination,” wrote Roosevelt in 1906.

Which raises an important question: Can hunting continue to be an ethical way of life—to protect nature, to fend off urban sprawl, to put food on the table—in the 21st century?

“Hunting is kind of an American legacy. If you like nature, you have to at least tip your hat to these hunters, who have given us the most successful conservation movement in the country.”

oday, as in the past, America’s 15 million hunters serve as

the primary breadwinners for conservation efforts in the

United States, with nearly $1 billion generated for such

efforts each year, according to the Department of Interior.

Hunting license fees cover the majority of wildlife management—

a concept crafted by famed ecologist Aldo Leopold, who

also developed the National Wilderness Preservation System—in

states like Maryland. And for every firearm or box of ammunition

sold in America, a federal excise tax is directed back to the state level

to specifically fund local wildlife projects, thanks to the hunter-lobbied

1937 Wildlife Restoration Act. Maryland received some $7.2 million

in 2020.

oday, as in the past, America’s 15 million hunters serve as

the primary breadwinners for conservation efforts in the

United States, with nearly $1 billion generated for such

efforts each year, according to the Department of Interior.

Hunting license fees cover the majority of wildlife management—

a concept crafted by famed ecologist Aldo Leopold, who

also developed the National Wilderness Preservation System—in

states like Maryland. And for every firearm or box of ammunition

sold in America, a federal excise tax is directed back to the state level

to specifically fund local wildlife projects, thanks to the hunter-lobbied

1937 Wildlife Restoration Act. Maryland received some $7.2 million

in 2020.

There are also additional fees, like the Federal Duck Stamp, required by all waterfowl hunters, which directly aids the purchase and protection of wetland habitat—dynamic ecosystems considered as vital as rainforests and coral reefs—with six million acres conserved since the program began in 1934. Through fundraising efforts, pro-hunting nonprofit organizations have also made similar progress, like Ducks Unlimited, which has conserved some 55,000 acres in Maryland, and the National Wild Turkey Federation, which has restored 40,000 acres of northeast forest.

“Hunting is kind of an American legacy,” says Madison. “If you like nature, you have to at least tip your hat to these hunters, who, through their organization and personal predilections, have given us a lot of public land and the most successful conservation movement really anywhere in this country.”

But hunting skeptics are not convinced: Doesn’t more habitat just mean more hunting? Not necessarily. Hunting remains a highly regulated activity, with Departments of Natural Resources using annual population estimates, harvest data, and the advice of a gubernatorial advisory commission (which in Maryland includes a Humane Society scientist) to determine both season lengths and bag limits that maintain sustainable populations. When those numbers shift, so do regulations, such as the elimination of Delmarva fox squirrel hunting, or the recent reductions to a 30-day, one-bird-a- day Canada goose season, after the species experienced a poor hatch on their spring nesting grounds in Canada.

Readying a spread of decoys; a wood-duck box in wait.

“Everything we allow people to take through hunting is done in a way that’s sustainable, scientifically grounded, well-regulated, and, in some cases, provides a management objective,” says Paul Peditto, director of the DNR’s Wildlife and Heritage Service. “It is never going to result in these animals being wiped out.”

Still, many opponents struggle with the argument of protecting wildlife by hunting and, often enough, shooting it, with some 78,275 white-tail deer, 54,600 Canada geese, and 27,500 mallard ducks killed in 2020. After all, animals, like us, are sentient creatures, and therefore experience pain and suffering.

“Hunting might have been necessary for human survival in prehistoric times, but today most hunters stalk and kill animals merely for the thrill of it, not out of necessity,” states the website of animal-rights activist group PETA. “This unnecessary, violent form of ‘entertainment’ rips animal families apart and leaves countless animals orphaned or badly injured when hunters miss their targets.”

It’s not entirely an overstatement. One 2008 study by the Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies found that managed archery hunts in Charles County corresponded with an 18 percent wounding rate for deer that were shot but unrecovered. In 2014, Maryland enacted a “wanton waste” law, making it illegal to intentionally injure or kill a deer without an attempt to retrieve it. Dogs are often called in as reinforcements, be they hired tracking hounds to help trail a buck, or a waterfowl hunter’s retriever, like Ruddy, who is trained to recover birds. Geese do monogamously mate for life, though if one dies, the other may eventually re-pair.

Death is indeed a brutal fact of hunting, which some hunters wrestle with every time they pull the trigger.

“When I killed my first deer, I cried like a baby,” says the DNR’s Peditto, who grew up hunting small game like squirrel and pheasant in New Jersey. “I was overwhelmed with emotion. I’ve been with many other hunters [during their first kill], including my son, who was 10 when he got his first deer. We high-fived and hugged and then his chin started to quiver. If you don’t feel a certain amount of internal turmoil, I don’t think you should do it.”

A taxidermied deer.

Many hunters speak to the mixed emotions that come with a successful hunt. “There is a sadness that only hunters know, a moment when lament overshadows any desire for celebration,” wrote North Carolina hunter David Joy in The New York Times in 2018. “Life is sustained by death, and though going to the field is an act of taking responsibility for that fact, the killing is not easy, nor should it be.”

And myriad factors—ethics, laws, safety—dictate a hunter’s decision whether or not to shoot. Is the animal within range? Is there a clear shot? What is the likelihood of retrieving it? Will it be eaten?

Earnest’s hunting gun collection.

“We have this initial kneejerk reaction that all hunting is bad, that animals can suffer and suffering is always wrong and thereby killing one is always wrong, so you should just not and become a vegetarian,” says David Gordon, environmental ethics professor at Loyola University. “But let’s face it, hunters are probably more in tune with nature than people who simply buy meat from the grocery store. When you shoot something and see it die, you’re probably much more thankful for it. Holding hunters in negative judgement, you also have to realize that when you get in your car or turn on a light that burns electricity provided by coal or gas or oil, that contributes to climate change and global warming and drought conditions and forest fires and that also kills wild animals. You can’t immediately assume that because you’re not a hunter, you’re on the moral high ground.”

Along these lines, it is no coincidence that when the prestigious academic journal Science released a shocking report that North American bird populations had plummeted by nearly 30 percent over the last half-century, waterfowl were one of only two bird groups on the upswing, due in part to the citizen science of the hunting community, which reports tens of thousands of bird sightings to the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center in Laurel each year, which then inform state and federal regulations.

It is this sort of give-and-take relationship with nature that keeps many hunters coming back each season. In addition to the required hunter education course, where license applicants must pass a test on everything from gun safety and marksmanship to conservation principles, many hunters dedicate much of their own time to becoming a sort of amateur biologist. They study the animal’s habitat, diet, sounds, smells, movements, and behaviors, as well as a range of other natural elements that can influence a hunt: time of day, shift of tides, direction of the wind.

“Hunting is so much more than hunting,” says Timothy Beadell, 32, president of the Baltimore County chapter of Ducks Unlimited, who learned how to hunt during college and now seeks out ducks on the Eastern Shore, geese in Monkton, and deer in Deep Creek each winter. “It’s setting your alarm for 4 a.m., getting up in the pitch-black, making a pot of coffee, hopping in the truck with your buddy, putting a headlamp on, walking through the woods, the freezing cold, watching the day rise. Seeing a flock of 10,000 snow geese lift up and take off—it’s a borderline magical thing.”

“As I’ve gotten older, I’ve learned to take note of so much more than just the target,” says Kirk Marks, a 27-year-old Kent Island geologist and photographer. He learned how to hunt from his father, with the ritual passed down like baseball in some families, heading out into the surrounding waters and woods for everything from squirrel and rabbit to wild turkey. “It’s the songbirds, the mushrooms, the plants on the forest floor. It’s a more holistic picture, and a great excuse to learn about nature.”

A medley of taxidermied ducks.

Both millennials were drawn further into hunting by the locavore food movement. Field-to-table personalities like former Virginia chef Wade Truong of Elevated Wild, Michigan outdoorsman Steven Rinella of Netflix’s MeatEater series, and Duck Duck Goose cookbook author Hank Shaw have inspired a new class of young hunters to explore the culinary delicacies of wild game. This, in the wake of disrupted global supply chains, could be part of the reason why Maryland witnessed a three-fold increase in apprentice licenses for first-time hunters in 2020.

“They’ve really made it cool again to showcase what you can do with these rare ingredients,” says Marks, who cooks recipes like corned Canada goose, grilled dove, and spice-rubbed wild turkey. “My father was a hunter, fishermen, and gardener, and from a young age, he instilled this ethos of living off the land. It just made the most sense. It was the cleanest way to envision what was on my plate. It was the most uncomplicated approach to food. And it instills a lot of wisdom.”

In a 2013 survey, hunters said consumption was the primary motivation for hunting. But it’s not as simple as stuffing your freezer full of vacuum-sealed venison. Immediately after the kill, deer hunters typically field-dress the animal, removing its internal organs to preserve the quality of the meat, with many then hauling the game home to butcher themselves. In 2021, it is an intimately complex process rarely felt when purchasing chicken from the meat counter or ordering steak at a restaurant, without ever having to witness the death of that once-living being.

“Everyone has an impact on the earth, we’re all consumers,” says Beadell, who points to the conditions of industrial factory farms. “Those animals never see the light of day, they’re crammed into small spaces; it’s upsetting. I would rather know my food in and out, and how to humanely harvest it for myself, and have it last me through the winter.”

“It just made the most sense. It was the cleanest way to envision what was on my plate, it was the most uncomplicated approach to food. And it instills a lot of wisdom.”

Of course, there are other motivations for hunting, such as camaraderie, and yes, excitement. There are few experiences more exhilarating than watching Charles Rodney shouting in a Louisiana accent as his six dogs flush a rabbit out of the briars and brush on a bright February morning—a sort of elaborate, adrenalinefueled dance, with the cottontails more often than not outsmarting the hunters.

“So many people come to hear the dogs—we call it beagle music,” says Rodney, 70, who grew up hunting small game, once the everyman’s catch, in his native Baton Rouge before becoming a sought-after guide in the Mid-Atlantic. “They also want to learn how to do it. I consider myself half-hunter, half-professor.”

Charles

Rodney leads his six

beagles on a February

rabbit hunt.

Another factor that hunting advocates point to is wildlife management, particularly for animals far larger than rabbits that have begun to infringe on human territory. Especially divisive, the five-day black bear hunting season, for instance, is set to allow continued population growth but at a slower rate to better balance densely populated places like Baltimore County, says the DNR’s Peditto, while the year-round coyote season aims, in part, to abate potential predation on pets and livestock, with one recently spotted in Herring Run Park. But perhaps most of all, this model is essential in the case of white-tail deer.

It’s hard to believe today, but as recently as the 1930s, white-tail deer were a rarity in Maryland. Early colonists relied on them heavily for food and clothing, as well as exports to England, and cleared their forest habitat to provide sources of heat and shelter for the growing region. They were all but gone until World War II, when the progeny of a mere five deer, originally purchased from a Pennsylvania game farm for the Aberdeen Proving Ground, were relocated by the state across various counties in Maryland.

By the 1980s, fueled by residential development and modern agriculture that provided new habitat and food sources, along with the elimination of natural predators such as wolves and mountain lions, deer populations had grown so quickly that they began to outpace their carrying capacity. Car collisions became commonplace—2,381 dead deer were picked up by the State Highway Administration in 2020—while local residents lamented the loss of their landscaping and regional ecologists warned of the detrimental effects on forests. Overpopulation also leads to increased disease and starvation rates among the herds.

“Even with our management efforts, we struggle to maintain an appropriate number of deer,” says Clark Howells, watershed manager of the Baltimore City Department of Public Works, who oversees the archery seasons at the Loch Raven, Liberty, and Prettyboy reservoirs. “They’re eating all vegetation within reach, and without those saplings, when our trees die, we’re not going to have that regenerative capacity to replace them for the future.” They also prefer to eat native plants, giving an edge to invasive species.

A lanyard of bird calls.

It is estimated that there are now some 230,000 deer statewide, about 900 of which are killed on the city's reservoirs each season. Meanwhile, in Baltimore County, deer management at the Oregon Ridge and Cromwell Valley parks and Marshy Point Nature Center is contracted out to the USDA, whose sharpshooters conduct annual nighttime hunts to eliminate upwards of 100 deer, whose meat is then donated to the Maryland Food Bank. The state even attempted administering them birth control via tranquilizer dart, though it proved largely unsuccessful.

“In The Land Ethic, Aldo Leopold says that an interaction with the environment is right if it maintains the integrity, sustainability, and proper function of an ecosystem,” explains Loyola’s Gordon. “Within that context, some forms of hunting are okay. If you’re going out into the forest because you’re bloodthirsty and want to kill something, that’s the bad kind. But I don’t think any true hunter revels in making an animal suffer. Even though they’re taking a life, most want to do so in a way that’s as quick and painless as possible.”

Of course, as with any demographic, there are always a few bad apples, with 876 natural resource violations recorded in 2020. While some do pertain to more notable offenses such as shooting out of season, over the limit, or with the aid of bait, the largest portion are related to hunting on private land without written permission, while many others concern minor infractions such as failure to wear the required fluorescent orange.

“Some people are going to cheat no matter what, and when I got into this 60 years ago, there was a lot of cheating,” says Bo Earnest. “My dad was always very scrupulous. As soon as the sun came down, you had to unload your gun, even if there was a duck flying right at you. At this point of my life, I think of myself more of a naturalist than a hunter."

Earnest’s property is speckled with over 100 wooden bird houses, as well as several ponds that serve as dedicated sanctuaries—no hunting allowed. Southeast of the pine trees, a longdead sunflower field still stands in the middle of winter, a remnant of autumn hunts by his Legal Limit Dove Club, named for a commitment to always shooting under state restrictions.

“The majority of the time, I’m just sitting out here with binoculars,” says Earnest. “One morning, I was in the blind waiting for ducks when a kestrel came and landed on my shotgun barrel. He looked at me, I looked at him, and then he flew off. You see some extraordinary things if you spend a lifetime in the marsh.”

Goose decoy parts; Loading a shotgun for rabbit hunting; Earnest moves through the marsh; empty shells in a former dove field.

arnest is something of a disappearing

breed, and as longtime sportsmen

like him begin to age out of the

tradition, hunting continues on its

six-decade decline, with hunters

now making up just about five percent of the

U.S. population—or two percent in Maryland—

half of what it was 50 years ago.

arnest is something of a disappearing

breed, and as longtime sportsmen

like him begin to age out of the

tradition, hunting continues on its

six-decade decline, with hunters

now making up just about five percent of the

U.S. population—or two percent in Maryland—

half of what it was 50 years ago.

Roughly 40 percent of Maryland hunters are Baby Boomers, and the joining ranks of millennials, who increasingly connect to nature through non-lethal means such as hiking and biking, might not be enough to sustain the sport. There are barriers to entry, like the expensive equipment and land access required for deer and waterfowl seasons, worrying wildlife advocates about what this dwindling community might mean for the future of conservation.

Ninety-three percent of Maryland hunters are also male, and nationally, they are overwhelming white. Half consider themselves politically conservative, and nearly the same percentage values the Second Amendment as much as conservation. A record 23 million guns were sold during the pandemic last year, superseding the previous high following President Barack Obama’s reelection, and those taxes brought a 65 percent increase in federal funding for wildlife, which might not matter if state budgets, driven by local hunting revenues, are not able to meet the match required to receive it.

Both government agencies and nonprofits are working to recruit a newly diverse generation of hunters through the likes of mentored and women-forward programs, while also retaining and reactivating present and past participants.

“Hunting spawns generational connection. The best conversation my son and I ever had was side by side in a tree at 5 a.m., talking about life as we watched maryland wake up around us.”

Rodney in the pines; Canada geese overhead.

A redwing blackbird sits in the morning sun.

“Honestly, I’m a bit concerned,” says Deborah Landau, ecologist for the Maryland-D.C. chapter of The Nature Conservancy, which allows hunting on its wildlife preserves. “The eyes that they have on the ground are so valuable to us, especially the older hunters who have been here year after year. I get such joy out of reading their annual reports, where they leave notes about seeing an otter or coyote or certain songbirds, offering wonderful little windows into the land. They can teach us a lot about what’s going on here.”

Meanwhile, a 2021 statewide poll found that 90 percent of Marylanders expressed support for Program Open Space, a local effort aimed at conserving land in the state, including parks, forests, and farms. Across those 319,000 acres, visited by 17 million people last year, dozens of hunter-funded projects are underway—from planting trees, to maintaining nature trails, to restoring habitat for once-flourishing small-game species such as quail, grouse, and woodcock, as well as countless other animals that are not and will never be hunted.

“Everyone who lives in or travels through Maryland benefits from those dollars,” says Peditto, noting that less than one percent of the wildlife managed by his department is hunted. “To this day, hunters are some of our most passionate stewards. You can make a fair argument that a birder or butterfly enthusiast also wants to protect wild spaces, but it’s hard to develop that ethic and appreciation until you sit out there for hours and take in these moments that most humans never experience.

“Very few people intentionally stand in a field at dawn or a forest while night arrives,” he continues. “You don’t hear stories of many wildlife photographers going into the woods for so much time with their sons and daughters or the grandparent who taught them in the first place. Hunting spawns generational connection. The best conversation my son and I ever had was side by side in a tree at 5 a.m., talking about life as we watched Maryland wake up around us.”