History & Politics

Up Hill Climb

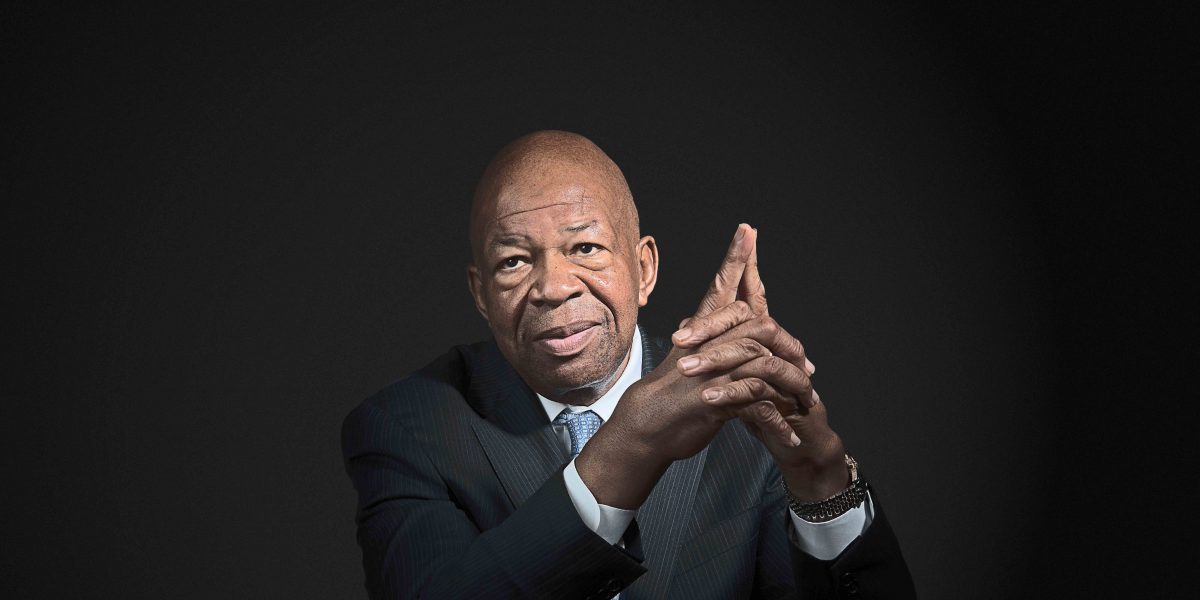

Carrying lessons learned from his humble roots, Elijah Cummings has become a national leader on Capitol Hill.

Cummings remembers running home from church on Sundays to listen to Martin Luther King Jr.’s speeches on WWIN-AM radio.

Raised with six siblings in a narrow row house in South Baltimore’s historically black Sharp-Leadenhall neighborhood, Elijah Cummings can recall any number of indelible childhood experiences. Beyond attending a poor, still segregated elementary school, he was among the first children to integrate the Riverside Park swimming pool in the summer of 1962.

“People were throwing bottles, rocks, and screaming,” he says, shaking his head, “calling us everything but a child of God.”

He remembers running home on Sundays from the church where his father was a preacher to listen to Martin Luther King Jr.’s speeches on WWIN-AM radio. He also remembers being a teenager and getting stopped by police while returning home one night—from his job at the Baltimore Country Club—past the citywide curfew following the 1968 riots.

But there are other memories, seemingly less profound at the time, which also left their imprint.

“My father, a former South Carolina sharecropper who moved north so his children could be better off, worked long hours at Davidson Chemical doing manual labor,” recalls the 63-year-old congressman, sitting in his midtown Baltimore office. “And he was happy to work, and to work overtime to make money to support us. But when he came home, he used to sit in his car, sometimes for an hour. Everyday. It didn’t matter if it was 80 degrees, 90 degrees, or 5 degrees.

“We all knew not to disturb him, and it’s funny, too, there were not a lot of cars in the street in those days,” laughs Cummings, himself a tireless worker by all accounts. Years later, Cummings continues, he asked his father—although he suspected the reason—why he sat in the car. “He told me that he was often treated badly at work, dealing with discrimination, and he didn’t want to bring those things, any bitterness, into our home,” Cummings says, pausing and getting emotional. “He did not want to make us victims as well. He always came into the house with a gentle smile.”

He is recalling this story as he’s asked about his dust-up this spring with Rep. Darrell Issa, the House Oversight Committee chairman, which went viral and thrust Cummings into the national spotlight. (Cummings is the committee’s ranking Democratic member.) A half-billionaire California businessman, Issa cut off Cummings’s microphone during a key IRS hearing, literally making a slashing motion with his hand across his throat to signal sound technicians during Cummings’s opening statement. It was an egregious act, arrogant and disdainful, and a clear violation of House procedure. Anyone in Cummings’s seat would’ve been understandably angry, ready to throttle Issa. But Cummings maintained his composure—his father, who passed away 14 years ago, certainly would’ve been proud—trying only to make his case, passionately for sure, for the Baltimore congressman is nothing if not a man who wears his heart on his sleeve.

“It’s not just my voice that was being shut down,” Cummings says. “Remember what I said: ‘I represent, we represent, over 700,000 people.’ What about our voice? ‘Shut it down [Issa said].’ That’s not the Democratic way.”

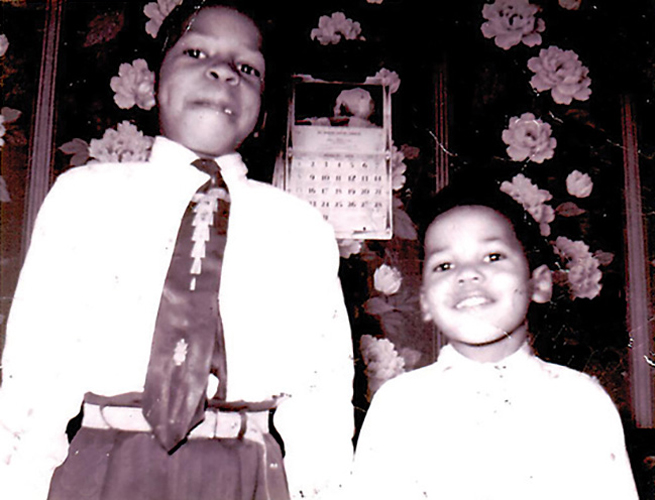

Elijah in a tie at a family event.

The controversy could’ve played out very differently in today’s hyper-politicized social-media environment if Cummings had overreacted. Instead, Issa issued a public apology the next day and the episode proved a galvanizing moment for Cummings, with people stopping him in airports across the country to tell him that they appreciated the way he handled the episode.

“Of the many things I learned from my father—and neither he nor my mother completed elementary school because they went to work in the fields—was to treat everyone with equal respect and not to speak or act out of anger,” Cummings says. “Because when you do, the person only hears your tone, they don’t get the message.

“And,” Cummings adds, tapping a finger to the table for emphasis, “you’ll lose sight of the bigger picture. You’ll get so caught up in who you are fighting, you’ll forget what you are fighting for—and it’s the what that is important.”

Today, Cummings is widely viewed as following in the footsteps, even surpassing, the tradition of leadership set by his 7th District predecessors, Parren Mitchell, the first African-American elected to Congress from Maryland, and Kweisi Mfume, who later led the NAACP. Their peers, for example, elected all three as chairman of the Congressional Black Caucus. Despite his ascension in Capitol Hill, he’s in no risk of losing sight of what he’s fighting for, or where he’s come from. That would be next to impossible for Cummings, who has now lived in the same West Baltimore, Madison Park row house for more than three decades. Around the block from his front stoop—where he’s known to occasionally feed the neighborhood pigeons—sit vacant homes, a drug recovery house, senior apartments, and a blighted public-housing complex scheduled for demolition. His home here has been burglarized, his car broken into several times and, once, he was robbed at gunpoint by two men with sawed-off shotguns.

“I don’t live in the inner city. I live in the inner-inner city and there are not a lot of congressman who grew up in the inner city, let alone still live there,” says Cummings, who has spent most of his career, including his 14 years in Maryland’s House of Delegates, focused on the economic, education, and heath-care issues that are intrinsic to his district. “It is an important voice to bring to Congress that needs to heard.”

Following the Tea-Party-led landslide in the 2010 mid-term elections, when control of the House flipped to Republicans, the White House and Democratic Party leadership knew they would need someone both smart and tough to go toe-to-toe with Issa, then the incoming House Oversight Committee chairman. Recognizing Issa would go after the Obama Administration aggressively, they feared New York Rep. Ed Towns, who had served as chair when the Democrats were in the majority, would get rolled over. Right behind Towns in seniority was fellow New York Rep. Carolyn Maloney, also elected in 1992, four years before Cummings.

Cummings, however, had earned broad respect for his performance on the committee, and had become the favorite of then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and House Minority Whip and Southern Maryland Rep. Steny Hoyer. After making a deal to move Towns aside, the House Democratic Steering Committee voted to leapfrog Cummings over Maloney, who had campaigned hard for the job.

Ever since, he has won kudos for his effectiveness in fending off high-profile Republican investigations into the Obama Administration’s handling of a variety of things, including, but not limited to, the stimulus package, the Affordable Care Act, the Benghazi tragedy, the “Fast and Furious” program, and the IRS’s targeting of political groups.

“She said, ‘Children, there is a real pool. and it’s nice and deep, and you can swim to your heart’s delight.’ Those were her words: ‘To Your Heart’s Delight.’ SHE IS THE REASON I BECAME A LAWYER.”

“[Cummings] is passionate, knowledgeable, prepared, and he looks at the facts—he truly is an incredibly good lawyer,” says Terry Lierman, Hoyer’s former chief of staff who was in the room for the behind-the-scenes discussions that led to Cummings’s elevation to the critical House Oversight post. “That’s all part of it. But this also is not somebody angling for personal ambition,” adds Lierman, also a former Maryland Democratic Party chair. “He has great respect on both sides of the aisle, and that’s because he doesn’t just talk the talk of commitment to public service—all you have to know is where he’s lived for 32 years.”

University of Maryland Carey School of Law professor Larry Gibson, former Mayor Kurt Schmoke’s campaign manager, sees Cummings’s career, and in particular, his recent rise in Congressional stature in the context of that long line of local African-American leaders who made significant contributions to the city, state, and country. “When [Cummings] was elected to the House of Delegates in 1982, that was still on the heels of the civil-rights movement and several years before Schmoke’s first election,” Gibson says. “And then look at who held that congressional seat before him—Parren Mitchell and Kweisi Mfume. All became powerhouses in Congress. That tradition of leadership goes back in Maryland. You can link it to Clarence Mitchell Jr., [a top Lyndon Johnson adviser who was instrumental in the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.]

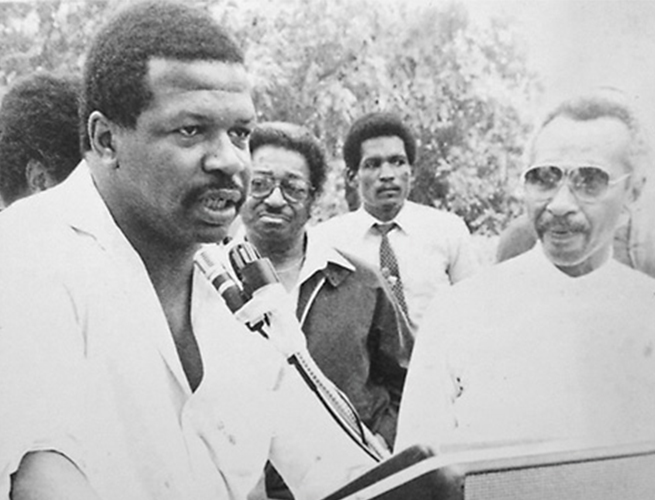

In front of television cameras on Capitol Hill.

“Without a doubt, he’s building on what they’ve done,” Gibson continues. “He’s also become the most powerful political figure in Baltimore. I know that. I teased him during the last election cycle that everyone was clamoring to get a picture with him on their campaign literature.” Increasingly, Cummings is also in demand nationally, stumping recently in North Carolina for Sen. Kay Hagan.

It is interesting that Gibson references Mitchell, the NAACP’s chief lobbyist for 28 years, because it was Mitchell’s wife, Juanita Jackson Mitchell, the first African-American woman to practice law in Maryland, who led the integration of the Riverside Park pool. In the process, she became a role model for a certain 11-year-old, who, with other black children, was accustomed to waiting in line to use the small wading pool in their crowded neighborhood. Cummings says he’ll never forget meeting Mitchell for the first time. “She said, ‘Children, there is a real pool,’ by which she meant an Olympic-size pool, ‘and it’s nice and deep, and you can swim to your heart’s delight.’ Those were her words: ‘To your heart’s delight.’

“The thing she didn’t tell us was that it was segregated,” adds Cummings with a belly laugh. “She is the reason I became a lawyer.”

Speaking at a rally with Parren Mitchell.

Like anyone, there are a number of influences that animate Cummings, who, at turns, can be thoughtful, direct, generous, and intense, and whose expressive countenance cannot help but reveal his current mood. If you have ever witnessed Cummings at a graduation, or similar event, you also know his booming baritone does not actually need a microphone when he’s fired up. There’s his father’s work ethic, his parents’ commitment to education—none of the Cummings children ever missed school—his Baptist faith, and no doubt the civil-rights era that he was born into. Mention efforts to make voting more difficult and Cummings responds viscerally, grimacing as his hands fall by his side.

But also, on a deeply personal level, being told so often that he “couldn’t”—couldn’t swim in the pool; couldn’t go to the newer, nicer white school; couldn’t go to college or get into law school—drove, and continues to drive, him. He’s not shy about admitting that he was labeled a special-education student because he understands how those labels affect children. He’s also proud enough to tell you that he excelled at Howard University, as he had at Baltimore City College high school, then an all-boys high school renowned for producing civic leaders. He remains legendary for his late-night and pre-dawn e-mails and phone calls, his ability to thrive on little sleep, and hustle between Baltimore and D.C., sometimes several times a day.

“It is hard to quantify the passion he brings to the job,” says Bill Cole, who, before serving as Cummings’s City Councilman and heading the Baltimore Development Corporation, worked on Cummings’s Congressional staff for seven years. “He’s up at three or four a.m. ready to work, seven days a week. I used to get those phone calls—at least until I had kids.”

The way Cummings tells it, he had to be coaxed into running for office. After earning his law degree from Maryland and entering private practice, he says he hadn’t considered politics until former Baltimore delegate Lena Lee reached out to him after she’d heard about the free tutoring course he’d set up with the help of other attorneys—black and white, he notes—to help African-American law school graduates crack the state bar exam. (Cummings passed on his first try.) “She’d been searching for a female African-American attorney to replace her, but after learning about the free course I’d organized, she said I was the kind of person she was looking for,” Cummings says. “She told me, ‘You’ll do.’ I owe her everything. Here I was, somebody she hadn’t known, and she started fundraising for me, getting a campaign going.”

Again, although Cummings rose to leadership in the General Assembly, he says he had no thoughts of running for Congress, figuring Mfume, only two years older, would remain until he was at least 70. “I heard about him leaving for the NAACP when I was driving home from Annapolis,” Cummings says. “Eventually, I decided I would rather live with the pain of trying and failing than not trying at all.” State Sen. Nathaniel McFadden initially ran as well, one of more than two-dozen candidates vying to replace Mfume, but says he realized Cummings was the right person for the job. “This is someone who rose to Speaker Pro Tem [the first African-American in Maryland history] because of his commitment, his command of the issues, and his understanding of the dynamics of a large governing body,” McFadden says.

With former Delegate Lena Lee.

McFadden notes something else that’s crucial about understanding Cummings—and it relates to his success on Capitol Hill, where even those on the other side of the aisle have difficulty saying anything bad about him. “Elijah may come from a background that is different than many in the General Assembly or Congress, but he has the ability to relate to anyone,” McFadden says. “He was named Speaker Pro Tem because he was able to build a consensus around issues.”

To McFadden’s point, former Republican Rep. Wayne Gilchrest, from Kent County on the Eastern Shore—only a two-hour drive, but worlds apart from West Baltimore—became close friends with Cummings when they served together on Capitol Hill. “You can tell pretty quickly when someone arrives in Congress who is about good public policy,” Gilchrest says. The pair even swapped districts for a day, with Cummings visiting dairy and pig farms, a Kent County school, and the Sassafras River National Resource Management Area. “You can get stereotyped as a congressman from an inner-city district or a rural district, but he’s someone who listens,” Gilchrest says. “It’s not about party or a limited ideology with him that he’s trying to keep under wraps.”

“It’s hard to quantify the passion Elijah Cummings brings to the job,” says bill cole. “he’s up at THREE OR FOUR a.m. ready to work, seven days a week. I used to get those phone calls.”

Remarkably, Gilchrest, a rare moderate Republican to be sure, says he’d love to see Cummings directing the lower house’s legislative chamber. “There is no better bipartisan member of Congress,” says Gilchrest, noting that he and Cummings were able to work together on Chesapeake Bay, Coast Guard, and maritime issues. “I think he’d be a great Speaker of the House. I really do—and you can be in the minority party and hold that position.”

Cummings participated in a similar district “swap” this summer with Utah Rep. Jason Chaffetz, a Mormon conservative, who also also sits on the House Oversight Committee. While Cummings gained an appreciation for Utah’s land-management issues—“he was all ears,” Chaffetz says—visiting, among other places, the desert red rock formations at Arches National Park, Chaffetz toured Baltimore’s Center for Urban Families and the Sandtown-Winchester Senior Center, learning about HIV treatment programs and issues such as food deserts. “I’d never heard of a food desert,” Chaffetz says, referencing the term for areas bereft of full-service grocery stores.

Later, both politicians went on MSNBC’s Morning Joe, talking up hopes for a new era of bipartisanship.

Unlikely as that may be, Cummings’s efforts at reaching out past his natural base haven’t gone unnoticed where it counts most—in his own district. The 7th district has been dramatically redrawn since Cummings’s initial congressional race 18 years ago, and now includes large swaths of Baltimore and Howard counties. Western Howard County can be conservative, but the changing demographics haven’t affected Cummings at the polls, where he won with more than 76 percent of the vote in 2012 and likely will do so again this November against long-shot Republican nominee Corrogan Vaughn.

Which is not to say everyone is an admirer. Cole, the former staffer, also mentions something Cummings faces that generally goes unreported—the vitriolic stream of racist mail, e-mail, social-media commentary, and phone messages that a leading African-American congressman receives. “It still bothers me to this day,” Cole says. For his part, Cummings says he deals with it, “by not dealing with it.”

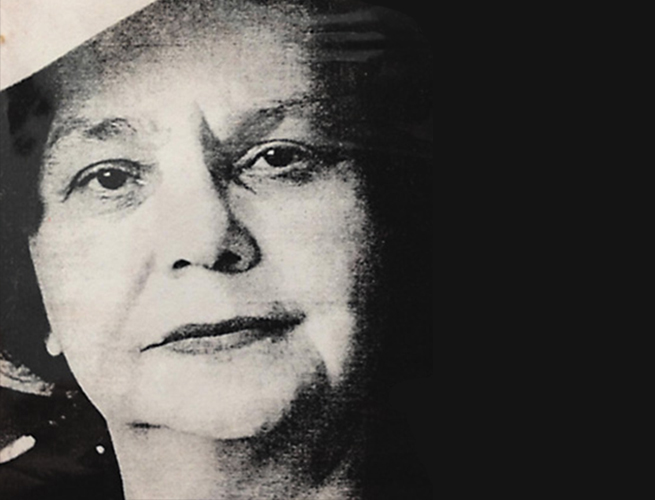

Juanita Jackson Mitchell.

“I can’t focus on that stuff,” he says. “If I do, again, I’ll just lose sight of the bigger picture. It’s not a productive use of my time.

“You know, I hadn’t thought about it in these terms before,” Cummings continues, echoing the wisdom of his father again, “But my dad, he’d been a farmer, and he was a very efficient, practical guy, and I’m sure that’s part of what I got from him, too.”

He also notes that his father, upon dropping him off at Howard University for his freshman year, told him that he and his mother had taken him “as far as they could,” and now he had to look for help from the college professors and others. Cummings says he’s remained grateful for the mentoring he received at Howard, as well as the support of others, such as Lena Lee and “Doc” Friedman, the Jewish South Baltimore pharmacist who gave him a job and encouraged him academically, going so far as to send him notes and the occasional $10 bill while Cummings was away at school.

“I have a responsibility to fulfill to those people, and that is to do my part for the next generation,” says Cummings, by which he means his work outside of Capitol Hill committees and legislative battles, dealing with what he calls “hands-on life.” More than politics, Cummings talks about serving on the boards of schools, holding foreclosure clinics, attending women’s roundtables, aligning constituents with resources, and working with the Elijah Cummings Youth Program, which sends city high-school students to Israel as part of a leadership development effort. “Wherever we are,” says his wife Maya Rockeymoore, founder of the Washington, D.C.-based Global Policy Solutions consulting firm, “people come up to him, usually sharing their problem and looking for some kind of assistance, and he always listens and tries to put them in touch with someone who can help. Sunday after church, there’s usually a line that forms.”

Cummings believes that what stops most of us from helping each other is that we think either it will cost too much or not matter in the end. His philosophy is simple, he says, “and that’s do something.

“Even if it seems small, there’s usually something that you can do,” Cummings says. “And this refers to helping people in my neighborhood, to my constituents, and it should apply to Congress, too. Governing is not always rocket science. If you can do something to help someone—that you can agree on—do it. And I tell you where this comes from—this goes back to my father, too.” Robert Cummings Sr., it’s worth noting, died of a heart attack shortly after a church-sponsored trip to the women’s state detention center in Jessup.

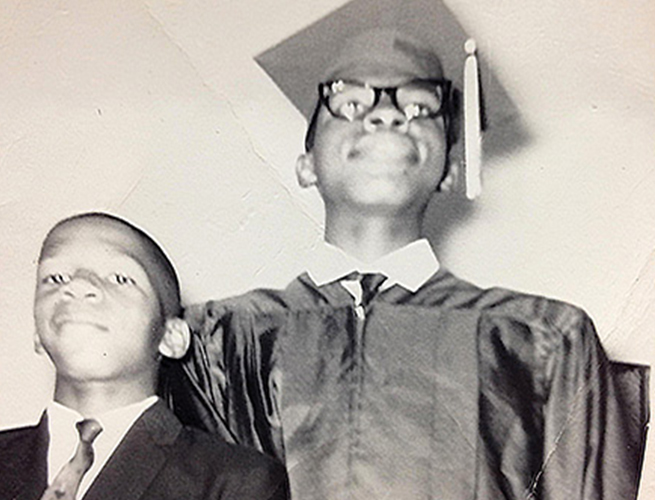

Cummings at his older brother’s graduation.

“Every Friday when he would get paid, my father would bring my mother a flower and Baby Ruth candy bar—my mother’s name is Ruth. And years later, I asked my mother about this, and she teared up. I said, ‘Mom, what’s up with getting emotional? It was a flower and candy bar.’ And she said, ‘It was the fact that he thought about it. And that he tried.’”

And so, Cummings says, the things that inform him today—that have informed his approach to life and work—go back again to a kind of concrete philosophy: You don’t have to solve the whole world’s problems today. But get something done.

“My father bought his wife a flower. He bought his wife a candy bar—and you may think it’s cheap or you may think it’s funny or you may think it doesn’t matter but he did it,” Cummings says. “He did it and I saw it and it influenced me. Do what you can. Do the best that you can.”