Arts & Culture

Bunny Tales

The club left an indelible impression on the young women who worked there.

“One of the comedians, Jackie Gayle, called me ‘the Yiddisha Bunny’—I’m from Northwest Baltimore’s Jewish ghetto,” laughs 68-year-old Sharon Bernstein Peyton, recalling the summer 50 years ago when she went to work as a cocktail waitress at the Mad Men-era Playboy Club then opening on Light Street. “And when I had my hair down, and because I didn’t wear a lot of makeup, he called me ‘the Beatnik Bunny.’”

Peyton had thought she wanted to go to art school, which she did, attending the Maryland Institute College of Art for a year after graduating from Forest Park High School in 1963. But once at MICA, she saw how talented everyone was and suddenly a career in art didn’t look like a good bet. Certainly tuition didn’t look like a great way to spend her parents’ money, given her doubts. “All I knew was I didn’t want to be a teacher, nurse, or secretary, and those were the jobs available to women.”

Then her boyfriend saw an ad for the soon-to-be Baltimore franchise of the Playboy Club—the latest addition to Hugh Hefner’s burgeoning string of nightclubs—and suggested she apply. “I finally got up the courage to go down there,” Peyton says. “The money was two or three times better than I could’ve made elsewhere.”

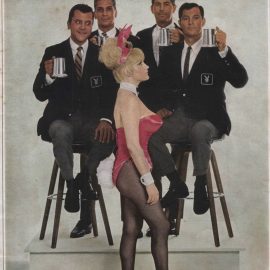

There’s no denying the club’s incredible male chauvinism—it’s Playboy’s foundational value after all. However, there’s also no denying it was an exciting place for an unsophisticated 18-year-old girl, rubbing shoulders with pro ballplayers, movie stars, entertainers, politicos, and the three-martini-lunch business crowd. “The feeling of being there at the very beginning was that it was ‘cool,’” Peyton says. “You never thought of blue-collar Baltimore as a cool place in those days. This was the coolest thing I knew.”

Cool enough that Hefner and his entourage flew in on his private jet for the opening party. (“Very shy,” Peyton reports. “Conversation was like pulling teeth.”)

More importantly, she discovered an interest in business as she absorbed firsthand Playboy’s corporate professionalism and attention to detail—from catering to clientele down to the design of the satin corset bunny suits with their requisite bow ties, cufflinks, ears, and fluffy white tails. “There was a week of training before we were allowed on the floor. We learned every brand of alcohol, memorized the 44-page ‘Bunny Manual,’ and had to master the ‘Bunny Dip [the graceful knee bend developed to keep buxom bunnies from spilling out of their costumes],’” says Peyton, who left and launched the popular Bluesette teen club with her boyfriend, and later graduated from then-Towson State University and went into media sales. “Working in three-inch high-heels was not fun, but everything I ever needed to know about superior customer service I learned as a Playboy bunny.

“Very shy,” Peyton says of Hefner. “Conversation was like pulling teeth.”

“You know what’s funny?” she continues. “I think Playboy figured they’d get ‘girl-next-door’ types who were kind of passive and what they really got were a lot of ‘girl-next-door’ types who were go-getters. It was a daring thing to do in those days to become a Playboy bunny.”

It’s fitting that almost exactly a half-century since the Baltimore Playboy Club opened, the 2014 International Playboy Bunny Reunion, which several former local bunnies plan to attend, will be held in Baltimore this month.

In hindsight, the Baltimore Playboy Club’s run from 1964 to 1977 is remarkable for any number of reasons—including hosting breakthrough comedians Flip Wilson and Richard Pryor (more on them later), and singers such as Jerry Vale and Al Martino. Well-known, well, playboys, such as Robert Mitchum and Joe Namath (more on them, too) were sure to stop in on their way through town. And the bunnies themselves became mini-celebrities, participating in parades, charity golf outings, and visits to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center accompanied by Cab Calloway and Bert Parks. But most remarkably perhaps, the club somehow managed to span three distinct and rapidly changing eras in American culture. Its 13-year existence literally stretched from the end of Camelot and the innocence of “I Wanna Hold Your Hand” to the Vietnam War and Summer of Love, and finally, to the Equal Rights Amendment movement and Ms. magazine.

Designed to bring the fantasy of Playboy magazine—jazz, cocktails, beautiful women—to life, from the outset, the clubs were surreal places of employment for young women, who came from all walks of life during formative periods in their lives. For many, it was their first or second job and saw them simultaneously thrust into the roles of breadwinner and sex symbol. But by the mid-’70s, the novelty was gone and the clubs had become anachronisms.

“It was always a paradox working there,” says Holly Royce, 72, the Baltimore club’s “bunny mother” manager during its first four years. Royce was, “another nice Jewish girl,” whose nickname was “Bunny Kelly” because there was another “Holly” at the club. “I had been a schoolteacher when my husband and I moved to Baltimore, but hated it,” she says. “I put my husband through dental school at the University of Maryland working there. I wanted to go to medical school or law school, too—and I later did go to law school for a period. But, here I was, despite all that sexism, 21, 22 years old, managing a nightclub and handling all the public relations.” Playboy, she adds, flew her out to Chicago and later, Atlanta for training. “I loved it. And it was more glamorous than teaching, getting invited to parties by [New York Yankees star] Joe Pepitone, who was dating one of the girls, or [Detroit Lions star] Alex Karras.”

She recalls a young Flip Wilson in her office pleading for his check so he could pay his hotel bill and Richard Pryor crying in the kitchen after his act. “It was early in his career and the audience didn’t get him yet,” she explains. She also recalls a “stoned” Robert Mitchum, “drunk, high, or both,” stumbling into an elegant, older woman, a guest, on the staircase. “She actually apologized, saying, ‘I’m sorry, Mr. Mitchum, I didn’t mean to shake you up.’ And he says—I’ll never forget it—‘Lady, you can shake anything of mine you want.’”

The experience changed her life, Royce says. “When my husband finished school, I ran his practice. I missed it, but after that, I was prepared for anything.”

Barbara Drumgoole, 60, worked at Baltimore’s Playboy Club from 1971 to 1973, essentially the middle of the club’s run. Seeking a job with flexibility around her junior college schedule, she still remembers driving downtown for her interview and audition. “You had to show up in leotards or a bathing suit, and so I wore a pair of black panty hose, a green sundress, and big platform shoes, which I took off to drive,” she chuckles. “I filled out the resume, you had to be a high school graduate, and my only job experience was at a sub shop. You did the ‘Miss America’ walk—the bunny mother present the entire time—and then they asked a whole lot of questions about your hobbies, your family, things like that. The owner, Abe Applebaum, and general manager, Nick Ferrare, were both wonderful, really.” (According to rumor, Applebaum, a former shirt salesman, opened the club with the financial backing of Julius Salsbury, a notorious former bookie and club owner on The Block, although Salsbury was never even seen in the Playboy club.)

Drumgoole worked as a cocktail waitress, sometimes as the “gift shop bunny,” “photo bunny,” or “disco bunny,” working on the club’s middle floor, above the stag Playmate bar in the basement and below the dinner-and-show, third-floor penthouse. She also pulled “door bunny” shifts, which is how she became friends with Bubba Smith, the Colts’ giant Pro Bowl defensive end.

“I didn’t know who he was—I hadn’t grown up in Maryland, my father was in the military—and he didn’t show me his key,” Drumgoole says, referring to Playboy memberships, considered status symbols of the day. “So I ran after him and touched his shoulder. He said, ‘You don’t know who I am? I am Bubba Smith.’ I said, ‘Who is Bubba Smith?’ and he started laughing. After that, whenever he came in, we’d talk about his family, his mother, anything.”

Bubba, however, never stirred things up as much as the time aforementioned New York Jets quarterback Joe Namath, aka Broadway Joe, walked in wearing his famous white mink coat. “Very handsome, very gracious,” she says. “Like a lot of people who came in, he treated us kind of like younger sisters,” Drumgoole says. “Everybody wanted his autograph, but what I remember most is that after he checked that coat, the bunnies kept running in there to put it on,” she laughs. “This was before the digital age or pictures would’ve been everywhere.”

Drumgoole also recalls greeting a table of her former high school teachers. “I had on the makeup, eyelashes, the hair done and everything—and in that costume they hadn’t recognized me at first. I started stuttering, but then I saw that they were more embarrassed than I was, which was cute,” she says. “One said, ‘You look a lot different than you did in high school,’ which was true.”

In fact, against the rules, she left the job with her costume—worth quite a bit on eBay today—proudly lending it to her daughter on Halloween. “She looks exactly like me, and it fit her perfectly,” Drumgoole says. “I can’t fit into it anymore, that’s for sure. But I’ve got gray hair and wrinkles, too, and I’m fine with all that.”

Similarly to Peyton and Royce, Elise Baker, who started at the club on her 18th birthday and turns 68 this month, wasn’t happy in her first job out of high school—bookkeeping in a cramped A&P Supermarket office. She credits her Playboy stint with helping her mature. She volunteered for the new Jamaican club when it opened, traveling and living outside the country for the first time.

And she had fun, too, running around town with Orioles like Jim Palmer—“the baby of the team, we were the same age”—and double-dating with Otis Redding and his girlfriend, catching a closed-circuit TV boxing match at the Civic Center. “I didn’t think it was exploitative at all,” she says. “The women wanted to be there. We all had different reasons.”

Not that there weren’t unpleasant moments and questionable working conditions, some of which up-and-coming journalist Gloria Steinem highlighted as an undercover bunny. Cocktail bunnies received no wages or health benefits, worked for tips, bought their own panty hose, and paid to get their hair done each week. Not to mention, inebriated men often found squeezing those fluffy white tails, strictly off limits, irresistible.

“I loved working there but walked out my last shift,” says Baker, whose bunny name was “Frankie” in those days. “A guy ran his hand down my backside and thigh and I’d had it. I threw my drink tray—I should’ve thrown it at him—and said, ‘I quit.’ Looking back, I was getting bored anyhow.” After leaving, she took the civil service exam, headed to the Social Security Administration, eventually moving into information technology. Retired, she lives on a small Virginia farm with a couple of horses.

“Fifty years ago? I’d sell my soul to have the body I did then,” she says. “But it was a great experience for me.”

Among the last bunnies, Margaret Charlene Rogers, 65, took a more circuitous route to bunnyhood, working at the club from ’74 to ’75 after an earlier cross-country trip to San Francisco. “I’d been a hippie, rebelling, smoking a lot of pot,” she smiles. “Going to work for Playboy, with all their rules, was like joining the military for me.”

Jets quarterback Joe Namath walked in wearing his famous white mink coat.

Like others, she describes the bunny costume—the pulled-in waist and built-in bra, supplemented when necessary—in near-reverential terms. “Everyone looked amazing,” she says, admitting that for her, being a bunny validated her femininity. At the same time, working there, “made me grow up,” she says. She went to nursing school and earned a B.A. after leaving Playboy. She could see the handwriting on the wall at that point.

“The city was transitioning, reflecting what was going on in the rest of country. By 1978, ’80, nearly all the clubs closed.”

Brenda Reiter, who grew up in Essex, never saw any high school teachers at the club. Although, ever the good Catholic girl, she received approval for her new job in 1972 from Father Stallings of St. Clare’s parish. “I taught Sunday school and didn’t want to embarrass anyone, but he gave it his blessing,” she chuckles. “Although I didn’t tell my parents right away. They still thought I worked at the insurance company.”

Reiter, to Peyton’s point about bunnies being mostly go-getters, had her own ulterior motive. “I’d fallen in love with skiing on a [Catholic Youth Organization] ski trip in ninth grade and knew the universe had bigger plans for me,” she says. “And that was the Colorado snow.”

Transferring to Denver’s Playboy Club, she graduated from college in Colorado, later working with handicapped children. She also got married and raised an Olympic snowboarder while remaining active in recreational sports, still leading snorkeling and paddleboard groups half the year in the Virgin Islands.

Reiter has few complaints about working at the club, saying she was treated well, better than other bars and restaurants where she later worked, and was fond of owner Abe Applebaum. “He looked at you in the eye when he talked to you, not at your chest. He told me I could always come back if things didn’t work out in Colorado.”

And like the others, Reiter says she gained confidence and poise working at the Playboy Club, taking away a newfound worldliness, as well.

All these years later, the bunny years remain vivid memories for Reiter—as they do for the other women who worked at Baltimore’s Playboy Club. Of course, we have to imagine, a lot of men have vivid memories of that period, too.

“Many years afterward, I came back to Maryland and went to Sunday Mass with my parents and ran into Father Stallings, who was by then, Monsignor Stallings,” Reiter recalls. “And I said, ‘Father, I’m sure you don’t remember me, but I just wanted to say hello. I grew up going to church here.

“I thought he might say, ‘Of course, the Sunday school teacher.’ I’d taught Sunday school for several years. But no, he says, ‘Oh yeah, the Playboy bunny.’”