History & Politics

Houses Have DNA, Too

Uncovering your home’s history has never been easier.

One of the bricks used in the early 1800s to build Ami Howard’s house has a dog’s paw print on it.

Just how Fido’s signature got there is part of the building’s bloodline, telling, in this case, the story of early 19th-century Redemptionist indentured servants, brought from the British Isles, who made bricks on site and laid them in the sun to dry. And before that brick could dry, Fido apparently made his mark.

It was a handy clue for Howard, but for an owner of an older home who wants to know the full history of the place, discovering the property’s pedigree is a bit more complicated than buying a home DNA kit and sending a swab to be analyzed. There are usually plenty of telltale signs, however, that can reveal much about not only its architecture, but also about the people who built it, those who lived there before, and what life in the home was like over generations.

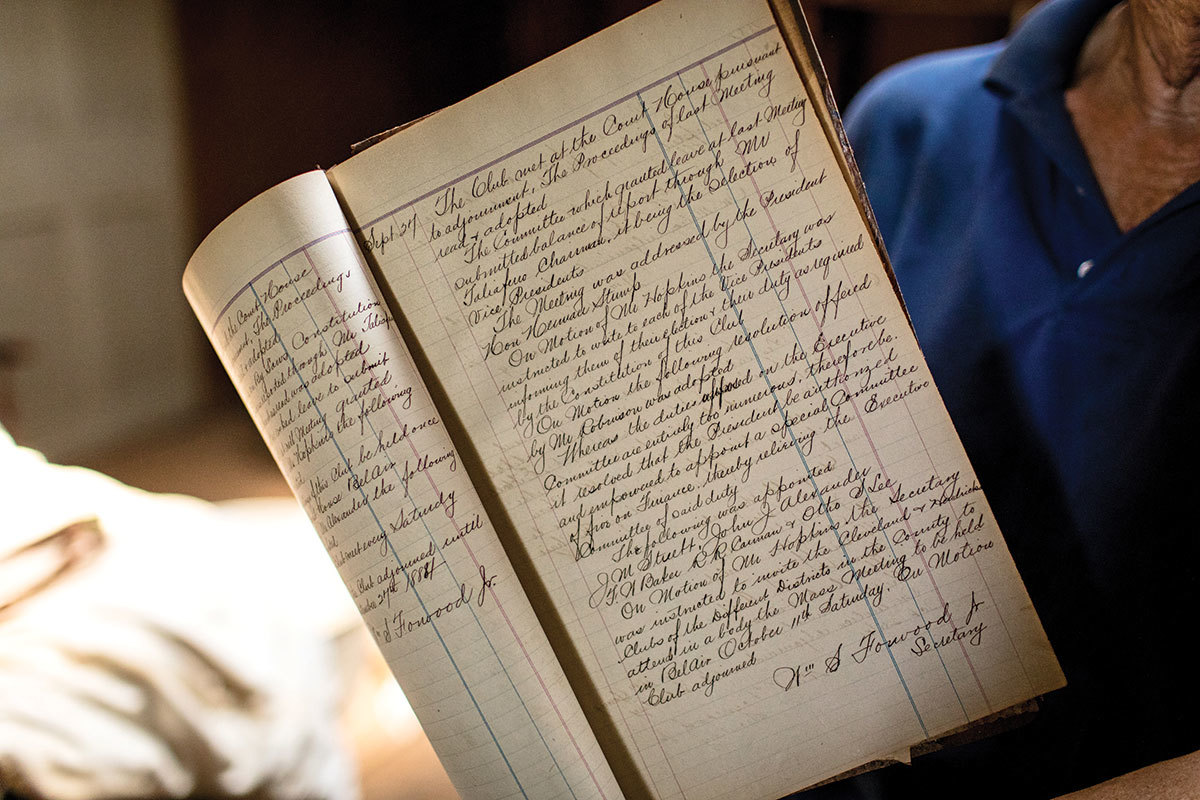

When Howard went to compile the house’s history, she was fortunate: She had plenty of oral history and papers scattered about the house, including ledgers detailing a previous owner’s elaborate purchases. Harford County historian Christopher Weeks also helped by providing more research and expertise, particularly on historic construction details. But there was more homework to do.

Her home, Olney Farm, sits on 135 acres in Harford County and has been in her husband’s family since 1855. It was built about 1810 for a Quaker family. They sold it to a family from Philadelphia to use as a summer home. And when that owner died, his widow sold it to the Howards (née Shrivers).

“They bought it as an investment after the Civil War,” Howard explains. “Then the son of the buyer, J. Alexis Shriver, either was deeded the house or bought it from his father. He moved in, had a family, and undertook many projects on the farm. He was also a unique salvager.”

“Unique” is an overused word, but it certainly applies in the case of the Shriver son: He collected marble fireplaces, ornate bookcases, and even an entire mirrored and paneled room from a home on Thames Street. He had a vault (most likely a Prohibition-era closet) hidden behind a secret bookcase in his bedroom. And, most famously, he hauled four massive columns from a house in Mt. Vernon by train and ox cart and erected them at the back of the house.

And then there are those clues: It’s apparent from the different brick patterns on the building’s exterior, for example, that the parlor was a later addition. That matches with family lore that the addition was built about 1850 to host a wedding.

An ornate fireplace added by owner Shriver; differences in brick pattern and color indicate different eras of construction —Justin Tsucalas

“The internet, and this was years ago, really helped a lot,” says Howard. “Because I had a lot of information to start with, I was able to go to the National Trust for Historic Preservation and look up references. But you can do a search for just ‘old house’ and you’d be amazed what resources come up.”

Where to begin doing the same sort of detective work on your own home? Eli Pousson, director of preservation and outreach at the nonprofit historical group Baltimore Heritage, offers a few pointers.

“We live in a golden era of historical research, whether you’re doing a family genealogy using DNA testing or you’re researching your neighborhood,” says Pousson. “The mass digitization of records has placed many resources you need for free online.”

Like Howard’s home, with its readily apparent addition, researching a home can start with an examination of the building itself. What is its architectural style? Can you see the outline of an old structure that was once attached? Is there evidence that windows have been bricked in? What materials are used? If you break through a wall and find newspaper used for insulation, what’s the date on them?

“There’s history in the structure itself,” says historian and author Jean Russo, PhD, who holds workshops on home research for the nonprofit Historic Annapolis. “You can go to the public records and track that information and relate it to the families who lived there.”

Researching architectural history isn’t a guarantee that anything interesting will turn up, though. Julie Saylor, a library associate with the Maryland Department of the Enoch Pratt Free Library, researched her own home in Moravia-Walther, which was built around 1904.

“One fellow had lived in the house for a very long time and, using the library’s criss-cross directories, I found a symbol that is used to indicate the owner is low-income,” she says. “Which didn’t shock me, because there was a lot in the house that looked to have not been maintained for a long time.” Beyond that, though, her hopes of uncovering anything juicy were dashed.

The Olney Farm contains a treasure trove of old memorabilia including propaganda from World War II. —Justin Tsucalas

The experts will tell you that uncovering home history is a process and history isn’t always stuff to be proud about. Old newspapers may reveal society-page stories of weddings hosted in a home—or violent deaths. Homes tell the stories of history, good and bad, including things like neighborhood segregation and fires.

“Home research is a winding road full of wrong turns, cul-de-sacs, and dead ends,” says Pousson. “I recommend people approach it less with the idea that they’re going to find certain specific facts and more with the idea that this is something they’re going to dip into and see what can be learned.”

Ami Howard made her own mark on her home’s history when she enclosed an existing Victorian folly—an ornamental structure—and added a patio to create her own secret garden. Generations from now, some future owner of the property may be able to figure out when that was done and by whom. But, ironically, she admits that if she were to build her own house, it would be nothing like the gracious old home she’s in now. She’d prefer something very modern and European, with lots of glass and very little clutter.

“But I love this house because of the history,” she explains. “I wonder about them, how things looked over the history, how they lived. Knowing the history makes it more of a home.”

Getting Started on Home History

The best place to start record-searching is the home’s deed. The nonprofit Baltimore Heritage has an extensive tutorial online that explains how to trace the history of the title using the Maryland State Department of Assessments and Taxation real property search. Those results provide a book number and a page number (sometimes known as a “liber” and “folio”) that can be searched in the open land records.

Deeds provide information such as the dates the property changed hands and surveyors’ “metes and bounds” descriptions. If you’re lucky, it will also have the name of the previous owner and the book and page number of their deed that will allow you to hop back through time.

“If you have owners’ names, you can go to the census records and see what you can find out about them,” says Jean Russo, PhD, who leads workshops on home research for the nonprofit Historic Annapolis.

In Annapolis and Baltimore City, in addition to census records, there are city directories that often provide information by address. Julie Saylor, a library associate with the Maryland Department of the Enoch Pratt Free Library, says the library has “criss-cross” directories back to the 1930s and city directories back to the 1790s.

And if you have the surnames of previous owners, The Baltimore Sun archives at the Pratt can also be useful.

“You can often find newsworthy events associated with the house by using The Baltimore Sun index,” says Saylor. “Sun articles are a very good source of information and could cover all sorts of interesting information, such as crimes associated with the house, classified ads for the sale or rent of the house, deaths associated with it, and so on.”

Maps, too, can help fill in some blanks, says Eli Pousson, director of preservation and outreach at Baltimore Heritage. “You learn different things from different sources,” he says. “Deeds tell you the names of who owned a property and details like when it changed hands, but it won’t tell you if your house was a boarding house or who the household members were beyond Mr. and Mrs. Smith.”

The U.S. Geological Survey has maps back to 1884, and both E. Sachse Bird’s Eye View of The City of Baltimore (1869) and Bromley Atlases for Baltimore City and County (covering the 1880s through 1915) are available through the Pratt.

A treasure trove of information can also often be found in an unlikely place: the Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps. From 1879 to about 1960, the map company, which allowed insurance firms to use their products, issued maps that were a record of everything in the city, particularly anything that could start a fire. The maps often note if a rowhouse had a business on the first floor, such as a blacksmith or shoemaker, and a residence above.

When it comes to being your own home’s genealogist, you just need to know where to look.