Arts & Culture

Cameo: Lawrence Burney

The True Laurels editor discusses his local arts publication and the importance of covering his hometown.

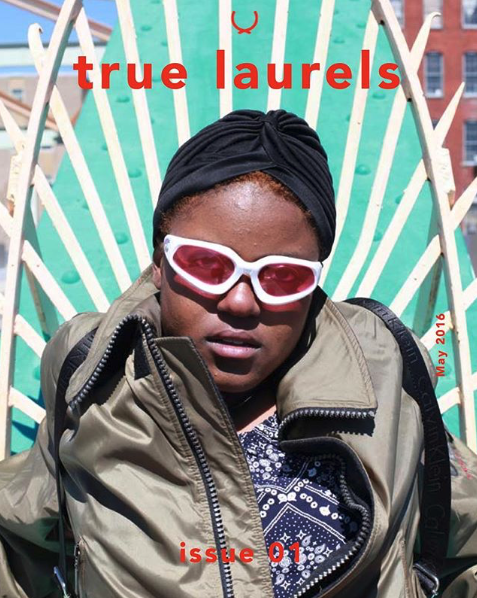

In 2011, Lawrence Burney started a local music and arts blog by the name of True Laurels. As a Baltimore native, he saw a hole in the city’s ever-evolving media landscape and in no time evolved his web-only format into an indie zine and now today’s integral print publication, featuring compelling photography and both first-person and reported stories on Baltimore’s black creatives. On the eve of True Laurels Issue 04, we sat down with Burney to talk about his musical upbringing, his gig at Vice, and the importance of giving back to the place where he grew up.

How did you get into writing?

My interest didn’t start until like my 12th grade year. I got into a lot of trouble in school. I was suspended for behavior-related things. I had this one writing teacher at City in ninth grade and we never liked each other. We always clashed. In the 11th grade, I had him again for college writing. We got into altercations—all this crazy stuff—but in the midst of all that, I still got As and Bs on all of my assignments. That’s something I kept in the back of my head: I must be pretty okay at writing if this guy, who has every reason to fail me, is still giving me As and Bs.

When it was time to start applying for colleges, I decided I was going to go to school for journalism. It wasn’t like a thing I did since I was a little kid; I stumbled into it because I needed to do something with my life.

Do you come from a creative family?

My mother is a writer. She actually went to University of Baltimore at the same time I did, for creative writing. She’s also a musician. She and my grandfather were in a jazz-funk band together, Wolf Pack, so I would travel with them to local gigs and be in studio sessions with them. We all lived in the same house for a good part of me growing up, so my alarm clock was my grandfather playing his guitar. He toured with George Clinton for like two tours as the drummer, and my mother opened up for Gil Scot-Heron one time on Charles Street when I was probably eight. I didn’t know who he was at the time, but I knew he was important by the way people talked about him.

So music was a part big of your upbringing.

In high school, my reputation amongst my friends was just knowing a lot of music. I would make them mixes and just impose my will on making them like the music that I liked. It’s basically what I’m still doing now. Then my daughter was born when I turned 20. I was feeling pressure from that. I had to do something. I had to gain some clarity on my life’s path. So I just combined those interests—the writing and the music. It was the end of 2011 when I made the True Laurels’ WordPress.

What was the rap scene like back then?

It was constructed in a completely different way at that time. Growing up, it was just battle rappers. Baltimore was more of a club music city. This whole rap scene really started in 2014 when Young Moose and Lor Scoota got hot. Before that, some artists like Los, Skarr Akbar, and Comp had some national success, but because technology wasn’t as sophisticated as it is now, people didn’t look at it as “the Baltimore scene.” Even when I started True Laurels, that wasn’t the case. When I went to UB was the first time I even started learning about central Baltimore. That part of town was not a place that most black people from Baltimore really knew too much about. We’re on the east and west sides.

Whereas, for at least the last decade, the local and national media has considered Baltimore’s “music scene” to be headquartered in Station North. Station North was just North Avenue when I was growing up. There was a Tyrone’s Chicken that I would go to with my grandfather after we played basketball at Druid Hill. He knew about the Copycat and all that because he was a musician, but I was never exposed to it. It was all new to me. The Windup Space. The Ottobar. It was an exciting time because I was being put in a new environment. I didn’t ever party with alternative types of black people or artsy white kids. I didn’t hang out around queer people or anybody who thought a little differently. That just wasn’t my upbringing. But I was learning about a new part of Baltimore while staying in tune with what was coming out of the parts of the city I was familiar with and bringing it all together.

You founded True Laurels as a music and arts blog in 2011.

I wanted to document the scene but also really try to paint a full picture of what inner-city, black Baltimore is. If you left it up to a place like the Urbanite, where I interned in 2012, you’d think Baltimore was only Hampden, Charles Village, Station North, and Mt. Vernon. This is still a struggle in the perception of Baltimore. When I’m in other places, people only know about the crime, the drugs, The Wire. That’s people’s main point of reference. And The Wire is a good show—mostly accurate in my opinion. I resisted watching it until I was in my 20s, but I ended up watching and it actually helped me make more sense of my own life. Even this whole Gun Trace Task Force can be tied back to things that were talked about on that show.

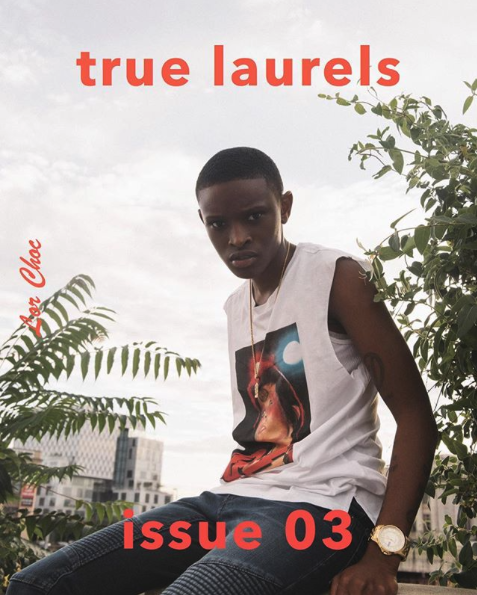

Speaking of the task force, your profile of local rapper Young Moose in Issue 03 was a great piece of journalism.

The problem is there hasn’t been someone who is actually a black person from the inner city writing these stories, with the nuance to show that black people from Baltimore are a very diverse group. This is an almost 65 percent black city, so not everybody is going to be living on a block that’s mostly vacant. That’s a lot of people’s reality, and part of my life I lived in those kinds of neighborhoods, too, but it’s not everything. There’s diversity that needs to be depicted, and I’m trying to pull all of those pieces together.

You are also a staff writer for Noisey, the online music publication of Vice, where you’ve written a number of stories on Baltimore artists. Do they give you a lot of creative freedom? They put a lot of trust in me. Through Vice, I’ve been able to tell stories about Baltimore that just don’t get told. I think stories like the one I wrote on Young Moose help people understand what it’s like for a person like him to grow up in a city like Baltimore—how they’re perceived by institutions, and how that trickles down into every part of their life. I do want to expand my voice and speak to different audiences, but if I can’t speak to the people that I come from, that’s not a win. That’s not enough for me.

You’ve recently done deep dives into the youth-driven music scenes of other cities like New Orleans and Johannesburg. Does that inform the work you do in Baltimore, or vice versa?

True Laurels has helped me form what I want to be as a journalist. Because I’m from a city like Baltimore—misunderstood and oversimplified— I’m really interested in regionality and how the politics of a city affect the way that the young people there operate. I have a lot of curiosity about how things work, here and around the world. To me, the music is not just the music. Music is the best introduction to any society. That’s why it has to be taken seriously.

You live in Brooklyn, but you come back to Baltimore every week?

At the very least, I’m here every 10 days, spending time with my daughter, trying to stay updated on what’s going on. I’m constantly in communication with the younger musicians on Instagram and YouTube. I’m 27 now and I realize that I am in some ways an elder statesman for these young people. Lor Choc’s 19. Deetranada’s 16. Young people drive culture, so you have to embrace them. Even when changing True Laurels from a fan zine to a more conventional magazine, I had to ask myself: what would a 17-year-old Lawrence think about this? In hip-hop culture, presentation and looking fresh matters. But there are artists here who are now starting to get traction and make it believable that you can actually get somewhere. And that’s why I feel encouraged to keep going—who knows what could happen next?

You’ve talked about True Laurels existing as documentation—a physical record of black culture in Baltimore.

You have to know the history and apply that to the present to know what’s coming next. That’s why, every week, I’m trying to post archival black Baltimore-related footage on the True Laurels Instagram. It’s important to inform people there has always been cool shit going on in this place for a long time. It’s helping me paint an even broader picture of Baltimore, and like The Wire, it’s helping me make sense of my own life.

Issue 4 comes out in June. Who are you really excited about right now?

Lor Choc is one of my favorite artists. I’m super impressed by her creativity. She’s a great storyteller, which I really enjoy. She has her own approach. But it’s not just artists. . . . I’m excited to see any young person from this place make strides on the national stage. Coming from here, a lot of people don’t think they can make it. The whole crab-in-the-barrel thing has become the narrative that people accept. I want people to recognize how amazing Baltimore is. If I can play any role in having less people settle, that’s what I’m trying to do. I’m trying to do publications. I’m trying to do film. I’m trying to do movies. The same way [film director] Ryan Coogler incorporated Oakland into the Black Panther, I want to do that for Baltimore. I’m trying to diversify the perception. I have no finish line for what True Laurels can be. I want to push it to every height that it could possibly achieve.